Dental fear

| Dental fear | |

|---|---|

| |

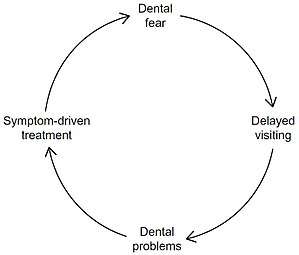

| Cycle of dental fear |

Dental fear, dental anxiety and dental phobia are quite often used inter-changeably. Dental fear is a normal emotional reaction to one or more specific threatening stimuli in the dental situation.[1][2] However, dental anxiety is indicative of a state of apprehension that something dreadful is going to happen in relation to dental treatment, and it is usually coupled with a sense of losing control.[1] Similarly, dental phobia denotes a severe type of dental anxiety, and is characterised by marked and persistent anxiety in relation to either clearly discernible situations or objects (e.g. drilling, local anaesthetic injections) or to the dental setting in general.[1] The term ‘dental fear and anxiety’ (DFA) is often used to refer to strong negative feelings associated with dental treatment among children, adolescents and adults, whether or not the criteria for a diagnosis of dental phobia are met.

Assessment

It is viewed as counterproductive to discuss dental fear with patients because it is believed that this may exacerbate the pre existing fear. Despite this common idea, it has been found that it is actually more beneficial in most cases to discuss dental fear with the patient. The first step in accommodating to patients with dental fear is to:

- Identify the patient has fear. This can be done through observation (constant moving, talking loudly, sweating) or by asking the patient directly.

- Then to create a conducive environment and open dialogue which can allow the patient to feel more comfortable in the dental setting.

Self- report scales that can be used to measure dental fear and anxiety include:

- Dental fear survey (DFS) which incapsulates 20 items relation to various situations, feelings and reaction to dental work which is used to diagnose dental fear.

- Modified child dental anxiety scale (MCDAS), used for children and it has 8 items with a voting system from 1-5 where 1 is not worried and 5 is very worried.

- The index of dental anxiety and fear (IDAF-4C+), used for adults and it is separated into 8 item module and then a further 10 item module.

- Corahs dental anxiety scale 1-4 questions and then 1-26 question. This scale has a ranking system and the second section with 26 questions has 1-4 options ranging from 'low' to 'don't know' which is used to assess dental concern. The first section with 1-4 questions has options a-e which are worth 1-5 points and the possible amount of maximum point is 20. Then depending on the result you rate the dental anxiety. 9-12 being moderate 13-14 being high, and 15-20 being severe.

Causes

Sexual abuse

Dental fear is associated with prior sexual abuse.[3]

Genetics

Dental fear was 30% heritable and fear of pain was 34% heritable.[4]

Other

Dental fear can be transmitted through social media, reading a comic dental paper, watching a movie involving gruesome dental scenes and listening to a fearful dental story from a friend or a family member. Dental fear can also arise from observation of other people attending for complex dental treatments.

Management

Dental fear varies across a continuum, from very mild fear to severe. Therefore, in dental setting, it is also the case where the technique and management that works for one patient might not work for another. Some individuals may require a tailored management and treatment approach.[5]

Psychological

Communication skills, rapport and trust building

- Verbal communication: It is important for dental practitioners to have a positive behaviour, attitude and communicative stance. Dental practitioners should establish a direct approach by communicating with the patient in a friendly, calm and non-judgmental manner, using appropriate vocabulary and avoiding negative phases. [6][1]

- Non-verbal communication: positive eye-contact, friendly facial expressions and positive gestures are essential to achieve an empathetic relationship between the patient and dental practitioner.[1]

By doing so, communication skills create a bond of understanding, trust and confidence between the dental practitioner and the patient.

Behavior modification technique

- Signaling: This is to allow the patient to communicate with dental professional during any stage of the treatment by means of previously-established signals with specific meanings.[6]

- Positive reinforcement: This technique aims to reward any positive efforts made by the patient and thus strengthens recurrence of those behaviours. Encouraging phrases (using positive voice modulation), such as “thank you for helping me by sitting still in the chair and keeping your mouth wide open”, or physical manifestation, such as a smile or thumbs up, encourages the patient to collaborate during the treatment.[5]

- Relaxation breathing therapy: Slow, deep and steady breathing for 2-4 minutes provides more oxygen to the body, thus reducing the patient’s heart rate.[7]

- Progressive muscle relaxation: Ask patient to focus on specific voluntary muscles and, in sequence, tense for 5-7 seconds and then relax for 20 seconds. As this sequence progresses, other aspects of the relaxation response also naturally occur.[1]

- Modelling: The patient’s behaviour can be altered through modelling. Modelling can be presented for viewing on televisions, computers or live by making the patient observe the behaviour of their siblings, family members or another patient with a similar situation. This conditions the patient to exhibit positive behaviour.[6]

- Guided imagery/Hypnosis: This technique uses a direct, deliberate daydream to create a focused state of relaxation. For example, the patient, seated in the dental chair, is taught to develop a mental image or asked to use their imagination skills to develop a pleasant, tranquil experience. This continuously guides the patient’s attention to achieve relaxation.[5]

- Systemic desensitization: It is strongly recommended that the treatment should be planned in phases (systemic desensitization) with techniques that are the least fear-evoking, painful and traumatic.

- - Early phase: Teach the patient relaxation techniques. The most commonly used relaxation techniques are, deep breathing and muscle relaxation.

- - Final phase: Gradually expose the patient to the treatment that is from the least to the most anxiety-provoking (from simple procedures to more extensive dental work).

Cognitive behavior therapy Dental fear often lead patient to cause unrealistic expectations about dental treatment, especially in children. Cognitive therapy aims to alter and restructure negative beliefs to reduce dental fear by enhancing the control of negative thoughts. “The process involves identifying the misinterpretations and catastrophic thoughts often associated with dental fear, challenging the patient’s evidence for them, and then replacing them with more realistic thoughts.”[6]

Medication

- Benzodiazepines

- Nitrous oxide

- General anesthesia: though it is discouraged due to possible but rare risk of death and high cost since it requires the involvement of specialist facilities.

Coping skills

Some common strategies for the patient to help get through the appointment:

- Speak up: Talk to the clinician about the coping skills that have worked for you in the past; Do not be afraid to ask questions; Agree on a signal you can give.[8]

- Distract yourself: Bring headphones and some music or an audio book to listen to; Occupy your hands by squeezing some soft toys or play with fidget toy; Ask your clinician for other options that may help in distracting yourself.[8]

- Deep breathing: Practice deep breathing anywhere.[8]

Epidemiology

Individuals who are highly anxious about undergoing dental treatment comprise approximately one in six of the population.[6] Younger people, female, and those who have experienced prior unpleasant dental experience have higher rates.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Seligman LD, Hovey JD, Chacon K, Ollendick TH (July 2017). "Dental anxiety: An understudied problem in youth". Clinical Psychology Review. 55: 25–40. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.004. PMID 28478271.

- ↑ Anthonappa, Robert P; Ashley, Paul F; Bonetti, Debbie L; Lombardo, Guido; Riley, Philip (2017). "Non-pharmacological interventions for managing dental anxiety in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012676.

- ↑ Larijani HH, Guggisberg M (2015). "Improving Clinical Practice: What Dentists Need to Know about the Association between Dental Fear and a History of Sexual Violence Victimisation". International Journal of Dentistry. 2015: 452814. doi:10.1155/2015/452814. PMID 25663839.

- ↑ Randall CL, Shaffer JR, McNeil DW, Crout RJ, Weyant RJ, Marazita ML (October 2016). "Toward a genetic understanding of dental fear: evidence of heritability". Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 45: 66. doi:10.1111/cdoe.12261. PMID 27730664.

- 1 2 3 Appukuttan DP (2016). "Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: literature review". Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dentistry. 8: 35–50. doi:10.2147/CCIDE.S63626. PMID 27022303.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Armfield JM, Heaton LJ (December 2013). "Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: a review". Australian Dental Journal. 58 (4): 390–407, quiz 531. doi:10.1111/adj.12118. PMID 24320894.

- ↑ "Dental fear and anxiety: Information for Dental Practitioners" (PDF). Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide. 2016.

- 1 2 3 Cianetti S, Paglia L, Gatto R, Montedori A, Lupatelli E (August 2017). "Evidence of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of dental fear in paediatric dentistry: a systematic review protocol". BMJ Open. 7 (8): e016043. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016043. PMID 28821522.