Orthodontics

| |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Orthodontist |

Occupation type | Specialty |

Activity sectors | Dentistry |

| Description | |

Education required | Dental degree |

Fields of employment | Hospitals, Private Practices |

Orthodontia, also called orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics, is a specialty of dentistry that deals with the diagnosis, prevention and correction of malpositioned teeth and jaws. The field was established by such pioneering orthodontists as Edward Angle and Norman William Kingsley.

Etymology

"Orthodontics" is derived from the Greek orthos ("correct", "straight") and -odont- ("tooth").[1]

History

The history of orthodontics has been intimately linked with the history of dentistry for more than 2000 years.[2] Dentistry had its origins as a part of medicine. According to the American Association of Orthodontists, archaeologists have discovered mummified ancients with metal bands wrapped around individual teeth.[3] Malocclusion is not a disease, but abnormal alignment of the teeth and the way the upper and lower teeth fit together. The prevalence of malocclusion varies,[4][5] but using orthodontic treatment indices,[6][7] which categorize malocclusions in terms of severity, it can be said that nearly 30% of the population present with malocclusions severe enough to benefit from orthodontic treatment.[8]

Orthodontic treatment can focus on dental displacement only, or deal with the control and modification of facial growth. In the latter case it is better defined as "dentofacial orthopedics". In severe malocclusions that can be a part of craniofacial abnormality, management often requires a combination of orthodontics with headgear or reverse pull facemask and / or jaw surgery or orthognathic surgery.[9][10]

This often requires additional training, in addition to the formal three-year specialty training. For instance, in the United States, orthodontists get at least another year of training in a form of fellowship, the so-called 'Craniofacial Orthodontics', to receive additional training in the orthodontic management of craniofacial anomalies.[11][12]

Methods

Typically treatment for malocclusion can take 1 to 2 years to complete, with braces being altered slightly every 4 to 8 weeks by the orthodontist.[13] There are multiple methods for adjusting malocclusion, depending on the needs of the individual patient. In growing patients there are more options for treating skeletal discrepancies, either promoting or restricting growth using functional appliances, orthodontic headgear or a reverse pull facemask. Most orthodontic work is started during the early permanent dentition stage before skeletal growth is completed. If skeletal growth has completed, orthognathic surgery can be an option. Extraction of teeth can be required in some cases to aid the orthodontic treatment. Starting the treatment process for overjets and prominent upper teeth in children rather than waiting until the child has reached adolescence has been shown to reduce damage to the lateral and central incisors. However the treatment outcome does not differ.[14]

Fixed appliances

Currently, the majority of Orthodontic Appliance Therapy is delivered using fixed appliances, with the use of removable appliances being greatly reduced. The treatment outcome for fixed appliances is significantly greater than that of removable appliances as the fixed type produces biomechanics that has greater control of the teeth under treatment: being able to move the teeth in dimensions therefore the subsequent final tooth positions are more ideal.

| 1993 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed | 49 | 82 |

| Removable | 50 | 17 |

Indications for Fixed Appliances

Fixed appliances are generally used when orthodontic treatment involves moving teeth through 3 axis planes in the mouth. These movements would include:

1) Rotations where the teeth are not conforming to the arch shape and there is contact displacements.

2) Multiple tooth movements where there may be crowding involved and the correction would involve the movement of numerous teeth in differing planes.

3) Bodily movement may be required to move a map-aligned tooth into the arch where the broad long axis of the tooth are correct but the tooth requires moving back into the arch maintaining the axial positions.

4) Tipping or changing the incline of the long axis of the tooth where the tooth may be proclined or retroclined and the tooth angulation is altered.

5) Root torquing - where the angle of the long axis of the tooth is changed with the position of the root being altered to facilitate a more naturally positioned crown and root prominence.

Contra-indications

- Poor oral hygiene: this predisposes to decalcification, caries, gingival hyperplasia, periodontal breakdown

- Active caries

- Poor motivation: treatment will last at least several months, patient needs to be committed to maintaining the highest levels of oral hygiene throughout this period.

- Mild malocclusions

Risks

- Decalcification

Plaque accumulation around the margins of brackets and bands can result in areas of demineralisation of enamel. It is very important that the patient maintains an excellent standard of oral hygiene throughout treatment.

- Root Resorption

This frequently occurs in orthodontic treatment, although it is usually small in amount. It is an irreversible outcome which is difficult to predict. Fixed appliances cause significantly more root resorption than removable appliances. Resorption occurs more frequently in adults and with greater amounts of tooth movement. Root resorption stops as soon as tooth movement stops so early detection is important.

- Loss of periodontal support

- Loss of bone support

- Failed treatment

- Soft tissue trauma

Types of Fixed Appliances

There are numerous fixed appliance systems that are in use today. These vary depending on the mechanical system employed and personal preference. In basic terms, a bracket is bonded onto the center of the tooth and wires are placed in the bracket slot in order to control movement in all 3 dimensions. Each individual bracket has a different shape, function and built in features for each particular tooth. Chair-side fitted appliances include Edgewise, Begg, Lingual, Self-ligating bracket systems. Laboratory fabricated appliances include Herbst, Quadhelix and MIA, Lingual and Transpalatal arches and RME screw appliances. The most commonly used appliance today is the Pre-adjusted Edgewise Appliance.

Brackets

The main parts of a bracket are:

- Wire slot

- Bracket base - can be used to spot weld onto orthodontic bands

- Tie wings

- Orientation marker - placed on disto-gingival aspect of tooth

Brackets can be made from stainless steel or porcelain. Brackets can be luted onto teeth using either a direct or indirect technique. Direct techniques involve conventional acid etch and chemical or light cured composites. The indirect technique involves the appliance's brackets being light cured to a working orthodontic model to allow a thin soft splint blow down appliance to be constructed over the model to aid placement of the brackets onto the teeth.

Orthodontic Bands

Used most frequently on either molar or occasionally premolar teeth. They are the means through which a force is applied to the tooth. They are made from stainless steel and have one or more tubes running through them. The large round tube is for a facebow and the smaller square tube is for the archwire. They can also have a number of pre-adjusted features built into their design, which will influence the position of teeth.

Archwires

Archwires are made from differing metal alloys, and are supplied as either straight lengths or as pre-formed archwires. There are different types of archwires including:

- Light to heavy

- Round / rectangular

- Braided or multi-strand

Archwires are carefully fitted into each bracket slot ready for ligation. Ligating is done using either elastic modules or thin wire ligatures: 'Quick Ties'. The closer the fit of the arch wires in the slot on the bracket, the greater the control of the teeth. As treatment progresses, thicker wires are used to fully control the teeth in three dimensions.

Auxiliaries

- Coils or springs - used to generate space by opening up a space by pushing teeth apart or to close space.

- Elastics - active components which come in the form of bands, threads or chain

- Long ligatures - used to tie several teeth together to generate anchorage

- Crimpable hooks - can have elastics or closing coils attached to them.[16]

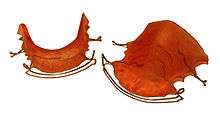

Functional appliances

When there is a maxillary overjet, or Class II occlusion, functional appliances can be used to correct the occlusion, it is recommended that the professional be a specialist in orofacial orthopedics to perform this typy ofand personal preference. The most common fixed appliance being used today is the Pre-adusted Edgewise Appliance. treatment, the originator of orthodontic therapy involving the use of oral activators by orofacial orthopedics was Viggo Andresen, Viggo Valdemar Julius Andresen ( Copenhagen , May 31, 1870 - October 8, 1950 ) was a Danish professor in Orthodontics in Oslo who is considered to be the inventor of the activator . In 1908 Viggo Andresen applied his bracket for the first time. Andresen used the activator to stimulate the development of the lower jaw and the lower teeth in growing children orthodontically. These may be fixed or removable.[17] Fixed dental braces are wires that are inserted into brackets secured to the teeth on the labial or lingual surface (lingual braces) of teeth. Other classes of functional appliances include removable appliances and over the head appliances, and these functional appliances are used to redirect jaw growth.[18] Post treatment retainers are frequently used to maintain the new position of the dentition.

During fixed orthodontic treatment, metal wires are held in place by elastic bands on orthodontic brackets (braces) on each tooth and inserted into bands around the molars. The orthodontic archwires can be made from stainless steel, nickel-titanium (Ni-Ti)[19] or a more aesthetic ceramic material. Ni-Ti is used as the initial arch wire as it has good flexibility, allowing it to exert the same forces regardless of how much it has been deflected. There is also heat activated Ni-Ti wire which tightens when it is heated to body temperature.[20] The arch wires interact with the brackets to move teeth into the desired positions.

Fixed orthodontic appliances aid tooth movement, and are used when a 3-D movement of the tooth is required in the mouth and multiple tooth movement is necessary. Ceramic fixed appliances can be used which more closely mimic the tooth colour than the metal brackets. Some manufacturers offer self-litigating fixed appliances where the metal wires are held by an integral clip on the bracket themselves. These can be supplied as either metal or ceramic.[21]

The surfaces of the teeth are etched, and brackets are attached to the teeth with an adhesive that is durable enough to withstand the orthodontic forces, but is able to be removed at the end of treatment without damaging the tooth. Currently there is not enough evidence to determine whether self-etch preparations or conventional etchants cause less decalcification around the bonding site and if there is a difference between them in bond failure rate.[22] The bonding material must also adhere to the surface of the tooth, be easy to use and preferably protect the tooth surface against caries (decay) as the orthodontic appliance becomes a trap for plaque. Currently a resin/matrix adhesive which is command light cured is most commonly used. This is similar to composite filling material.[23]

Anchorage for the appliance prevents unwanted movement of teeth and it can come from the headgear worn, the palate, or surgical implants.[24]

For young patients with mild to moderate Angle Class III malocclusions (prognathism), a functional appliance is sufficient for correction. Examples of functional appliances are: facemask, chin-cup, tandem traction bow or headgear.[25] As the malocclusion increases, orthognathic surgery might be required. This treatment comes in three stages. Prior to surgery there is orthodontic treatment to align teeth into their post-surgery occlusion positions. The second stage is surgery such as a mandibular step osteotomy or sagittal/bilateral sagittal split osteotomy [26] depending on whether one or both sides of the mandible are affected. The bone is broken during surgery and is stabilised with titanium plates and screws, or bioresorbable plates to allow for healing to take place.[27] The third stage of treatment is post-surgical orthodontic treatment to move the teeth into their final positions to ensure the best possible occlusion.[28]

A posterior crossbite malocclusion may be corrected using the quad helix appliance or removable appliances during the early mixed dentition stage (eight to 10 years), and more research is required for determining whether any intervention provides greater results than any other for later stages of dentition development. These crossbites are when the maxillary teeth or jaw is narrower than the mandibular, and can occur unilaterally or bilaterally. .[29] Treatment involves the expansion of the maxillary arch to restore functional occlusion, which can either be 'fast' at 0.5mm per day or 'slow' at 0.5mm per week. Palatal expansion can be achieved using either fixed or removable appliances.[29] Banded maxillary expansion involves metal bands bonded to individual teeth which are attached to braces, and bonded maxillary expansion is an acrylic splint with a wire framework attached to a screw in the palatal mid-line, which can be turned and opened to expand the maxilla.

Removable functional appliances are useful for simple movements and can aid in altering the angulation of a tooth: retroclining maxillary teeth and proclining mandibular teeth; help with expansion; and overbite reduction.[30]

Headgear works by applying forces externally to the back of the head, moving the molar teeth posteriorly (distalising) to allow space for the anterior teeth and relieving the overcrowding [31] or to help with anchorage problems.

The facemask aims to pull maxillary teeth and jaw forward and downwards to meet the mandible through a balanced force applied to the upper teeth. The mask rests on the forehead and chin of the wearer, and connects to the maxillary teeth with elastic bands.[25]

Some removable appliances have a flat acrylic bite plane to allow full disocclusion between the maxillary and mandibular teeth to aid in movement during treatment. An example of this is the Clark Twin Block. This design has two blocks of acrylic which disocclude the teeth and protrude the mandible. It is used to treat Class II malocclusion. [30]

Vacuum-formed aligners such as Invisalign consist of clear, flexible, plastic trays that move teeth incrementally to reduce mild overcrowding and can improve mild irregularities and spacing. They are not suitable for use in complex orthodontic cases and cannot produce body movement. They are worn full time by the patient apart from when eating and drinking.[32] A large benefit of these types of orthodontic appliance are that they suitable for use when the patient has porcelain veneers: as metal brackets cannot be bonded to the veneer surface.[30]

Adjunctive therapy

Adjunctive surgical and non surgical therapy have been researched as options to help reduce the duration of orthodontic treatment. Surgical intervention such as alveolar decortication, and corticision have been used in conjunction with orthodontic treatment to reduce the time spent in functional appliances, but more research is required into the possible effects of the surgery.[33] Non-surgical therapy involves the use of vibrational forces during treatment, but it has not been shown that this significantly reduces the treatment time, or increases the comfort for the patient.[34]

Extensive research has been done proving the effectiveness of functional appliances, but maintaining the results is important once the active treatment phase has completed.

Post treatment

After orthodontic treatment has completed, there is a tendency for teeth to return, or relapse, back to their pre-treatment positions. Over 50% of patients have some reversion to pre-treatment positions within 10 years following treatment.[35] To prevent relapse, the majority of patients will be offered a retainer (orthodontics) once treatment has completed, and will benefit from wearing their retainers. Retainers can be either fixed or removable. Removable retainers will be worn for different periods of time depending on patient need to stabilise the dentition.[36] Fixed retainers are a simple wire fixed to the labial surface of the incisors using dental adhesive and can be specifically useful to prevent rotation in incisors. Other types fixed retainers can include labial or lingual braces, with brackets fixed to the teeth.[36]

Removable retainers can include one known as a Hawley retainer, made with an acrylic base plate and metal wire covering the canine to canine region. Another form of removable retainer is the Essix retainer which is made from vacuum formed polypropylene or polyvinylchloride and can cover all the dentition.[37]

Diagnosis and treatment planning

In diagnosis and treatment planning, the orthodontist must (1) recognize the various characteristics of a malocclusion or dentofacial deformity; (2) define the nature of the problem, including the etiology if possible; (3) design a treatment strategy based on the specific needs and desires of the individual; and (4) present the treatment strategy to the patient in such a way that the patient fully understands the ramifications of his/her decision.[38]

Treatment planning is a crucial aspect in health care. In terms of orthodontics, it is important to consider the following aspects when arriving at a treatment plan for patients;[39] (1) aesthetics (consider the patient's concerns and expectations from the treatment), (2) oral health (consider patient motivation and the overall dentition. All patients who are to undergo orthodontic treatment need to maintain good oral health), (3) function and (4) stability.

Orthodontic treatment “should not compromise dental health [but] promote good function, and it should produce as stable a result as possible”.[39]

Before a treatment plan can be devised, it is important to establish a diagnosis. An in-depth orthodontic assessment of the patient is pivotal.

Based on the patient’s concerns/expectations and the diagnosis made, a list of ‘problems’ can be made. Depending on the problems, it is possible that there may be more than one course of treatment for the patient. It is important to have a list of ‘problems’ where you can list treatment options for each ‘problem’ and present this information to the patient along with the benefits and risks of each treatment option.

Malocclusions vary in severity and can sometimes be simple to treat or very complex to treat.

There are a few options for treating malocclusions with underlying skeletal problems;[40]

(1) Orthodontic camouflage: This means that the discrepancy is accepted, but the teeth are moved into a Class I relationship.

(2) Growth Modification: This treatment is only possible in the growing patient where orthodontic appliances are used to make minor changes to the skeletal pattern.

(3) Combined orthodontic and orthognathic surgical treatment: surgical correction of the jaw discrepancy in combination with orthodontics is performed to produce optimum dental and facial aesthetics. Orthognathic surgery can only be performed on patients who have completed growth.

Crowding of teeth is also common amongst the population. Treatment planning for crowding involves analysing the space required to relieve the crowding.

The amount of crowding present can be classified as: mild (<4mm), moderate (4-8mm) or severe (>8mm).[41]

Space can be created in the following ways:[41]

(1) Extractions

(2) Distal movement of molars

(3) Enamel stripping

(4) Expansion

(5) Proclination of the incisors

(6) A combination of any or all of the above

It is of paramount importance to take all the teeth present and yet to erupt into account and to consider the prognosis of each tooth in order to arrive at a treatment plan.

After a treatment plan has been devised, informed consent has to be taken from the patient. Informed consent includes giving the patient information about the malocclusion, proposed treatment/alternatives, commitment required, duration of the treatment and the cost implications.[42]

Malocclusions

Malocclusion is defined as an abnormal deviation either aesthetically, functionally or both from the ideal occlusion; the anatomically perfect arrangement of the teeth. The prevalence of malocclusions varies with a person’s age and ethnicity but not all malocclusions require treatment.[43]

Malocclusions are the result of a combination of both genetic and environmental factors. Key factors include:[44]

- Abnormal tooth germ position

- Delayed eruption

- Dilaceration (an abnormal development in tooth shape)

- Hyper & Hypodontia

- Impaction

- Loss of teeth

- Patient Habits (i.e. thumb sucking)

- Retention of deciduous teeth

- Skeletal development

- Pathology (i.e. cysts)

Classification of malocclusions

Skeletal classifications show the relationship of the maxilla to the mandible:[43]

- Class I: the mandible is 2-3mm posterior to the maxilla.

- Class II: the mandible is more than 3mm posterior to the maxilla.

- Class III: the mandible is more than 3mm anterior to the maxilla.

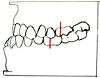

Incisor classification - The British’s Standards Institute classification is used to define the incisal relationship:[45]

- Class I: the lower incisor edge occludes with, or lie immediately below, the cingulum plateau (the middle third of the palatal surface) of the upper incisors.

- Class II division 1: the lower incisor edges lie posterior to the cingulum plateau of the upper incisors and there is an increase in overjet and the upper incisors are proclined or of an average inclination.

- Class II division 2: the lower incisor edges lie posterior to the cingulum plateau of the upper incisors and the upper central incisors are retroclined; the overjet is usually minimal but may be increased.

- Class III: the lower incisor edges lie anterior to the cingulum plateau of the upper incisors; the overjet is reduced or reversed.

Angle’s classification (Molar) is used to describe the first permanent molar relationship from normal to malocclusion:[45]

- Class I: the mesio-buccal cusp of the upper first permanent molar occludes in the buccal groove of the lower first permanent molar.

- Class II: the mesio-buccal cusp of the upper first permanent molar occludes anterior to the buccal groove of the lower first permanent molar.

- Class III: the mesio-buccal cusp of the upper first permanent molar occludes posterior to the buccal groove of the lower first permanent molar.

Other types of dental malocclusions can include:[45]

Overjet: the horizontal distance between the labial surface of the lower incisors and the upper incisal edge; the normal measurement is 2-3mm.

Overbite: the vertical distance between the upper and lower incisal edges. Normal is one-third to two-thirds overlap of the upper incisor to the lower incisor. An incomplete overbite is when the lower incisors do not occlude with the opposing upper incisors or the palatal mucosa when the buccal segment teeth are in occlusion.

Crossbite: A deviation from the normal bucco-lingual relationship. These can either be anterior or posterior but also unilateral or bilateral. Crossbites can be further broken down into

- Buccal crossbites: the buccal cusps of the lower premolars or molars occlude buccally to the buccal cusps of the upper premolars or molars.

- Lingual crossbites: the buccal cusps of the lower molars occlude lingually to the lingual cusps of the upper molars.

Anterior open bite: there is no vertical overlap of the incisors when the buccal segment teeth are in occlusion.

Posterior open bite: when the teeth are in occlusion there is a space between the upper and lower posterior teeth.

Crowding

Crowding occurs when one or more teeth do not have enough room to align within the arch. Crowding can be caused by a wide range of factors:[44]

- Delayed eruption - Delayed eruption results in adjacent teeth drifting and/ or tilting resulting in a loss of arch space. A similar effect is seen in the early loss of deciduous teeth.

- Developmental crowding of lower incisors - Inter-canine growth increases up to the age of 12–13 years, followed by a gradual diminution throughout adult life. This reduction is arch size is considered a developmental phenomenon

- Early loss of deciduous teeth - Whether due to caries, premature exfoliation or planned extraction – the early loss of deciduous teeth results in an increase in severity of pre-existing crowding. When crowding is present the remaining teeth will drift or tilt into the free space provided. The younger the patient is when the tooth is lost and the earlier in development the adjacent teeth are the more serve the effect.

- Hyperdontia - Hyperdontia is the congenital condition of having supernumerary teeth. Hyperdontia can results in crowding due to an increased number of teeth within the arch.

- Skeletal - The skeletal base, mainly controlled be genetics, governs the overall shape, size and relationship of the Maxilla and mandible.

- Soft tissue & patient habits - The forces exerted by the cheeks, tongue, lips and patient habits all play a role in the alignment of the teeth.

Orthodontic indices

Orthodontic indices are one of the few tools that are available for orthodontists to grade and assess malocclusion. Orthodontic indices can be useful for epidemiologist to analyse prevalence and severity of malocclusion in any population.[46]

Angle's classification

Angle's Classification is devised in 1899 by father of Orthodontic, Dr Edward Angle to describe the classes of malocclusion, widely accepted and widely used since it was published. Angle's Classification are based on the relationship of the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar and the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar.[47] Angle's Classification describes 3 classes of malocclusion:

- Class I: The molar relationship of the occlusion is normal or as described for the maxillary first molar, with malocclusion confined to anterior teeth [48]

- Class II: The retrusion of the lower jaw with distal occlusion of the lower teeth (or in other words, the maxillary first molar occludes anterior to the buccal groove of the mandibular first molars [48]

- Class II div 1: class II relationship with proclined upper central incisors (overjet)

- Class II div 2: class II relationship with lingual inclination of upper central incisors (retrocline) and upper lateral incisors overlapping the centrals

- Class III: The protrusion of the lower jaw with mesiobuccal cusp of maxillary first molar occluding posterior to the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar, with lingually inclined lower incisors and cuspids [48]

Angle’s classification only considers anteroposterior deviations in the sagittal plane while malocclusion is a three dimensional problem (sagittal,transverse and vertical) rather than two dimensional as described in Angle’s classification Angle’s classification also disregards the relationship of the teeth to the face.[49][50]

Massler and Frankel's index recording the number of displaced/rotated teeth

Introduced in 1951 by Massler & Frankel to produce a way to record the prevalence of malocclusion which will satisfy 3 criteria: simple, accurate and applicable to large groups of individual; yield quantitative information that could be statistically analysed; reproducible so that results are comparable. This index uses individual teeth as unit of occlusion instead of a segment of the arch. Each tooth is examined to determine whether it is in correct occlusion or it is maloccluded.[51]

The total number of maloccluded teeth is the counted and recorded. Each tooth is examined from two different aspects: occlusal aspect and then the buccal and labial surfaces with the exclusion of third molars. Tooth that is not in perfect occlusion from both occlusal aspect (in perfect alignment with contact line) and buccal aspect (in perfect alignment with plane of occlusion and in correct interdigitation with opposing teeth) is considered as maloccluded. Each maloccluded tooth is given a value of 1 while tooth in perfect occlusion is given a score of 0. A score of 0 will indicate a perfect occlusion; score of more than 10 would be classified as sufficient severity that would require orthodontic treatment; score between 1 to 9 would be classified as normal occlusion in which no orthodontic treatment is indicated.[51]

However, while this index are simple, easy and able to provide prevalence and incidence data in populations group, there are some major disadvantage with this index: primary dentition, erupting teeth and missing teeth are left out in the scoring system and difficulties in judging conformity of each tooth to an ideal position in all planes.[52]

Malignment Index

Introduced in 1959 by Lawrence Vankirk and Elliott Pennell. This index requires the use of a small plastic, gauge-like tool designed for assessment. Tooth rotation and displacement are measured.[53]

The mouth are divided into 6 segment, and is examined in the following order: maxillary anterior, maxillary right posterior, maxillary left posterior, mandibular anterior, mandibular right posterior and mandibular left posterior. The tool is superimposed over the teeth for the scoring measurement, each tooth present is scored 0, 1 or 2.[53]

2 types of malalignment are being measured, rotation and displacement. Rotation is defined as angle formed by the line projected through contact areas of observed tooth and the ideal arch line. Displacement is defined as both of the contact areas of the tooth are displaced in the same direction from the ideal alignment position.[53]

- Score of 0 represents ideal alignment with no apparent deviation from the ideal arch line.

- Score of 1 represents minor malalignment: rotation of less than 45º and displacement of less than 1.5mm

- Score of 2 represents major malalignment: rotation of more than 45º and displacement of more than 1.5mm

Handicapping Labiollingual Deviation Index (HLDI)

This index was proposed in 1960 by Harry L. Draker. HLDI was designed for identification of dento-facial handicap. The index is designed to yield prevalence data if used in screenings. Measurement taken are as following: cleft palate (all or nothing), severe traumatic deviation (all or none), overjet (mm), overbite (mm), mandibular protrusion (mm), anterior open bite (mm), labiolingual spread (measurement of tooth displacement in mm) [54][49] HLD index is used in several states in the United States, with some modifications to its original form by the states that used them for determining orthodontic treatment need.[55][56]

Occlusal Feature Index

Occlusal Feature Index is introduced by Poulton and Aaronson in 1961. The index is based on four primary features of occlusion that is important in orthodontic examination.[57] The four primary features are as following:[57]

- Lower anterior crowding (canine to canine area)

- Posterior cuspal interdigitation (right posterior premolar to molar area)

- Vertical overbite (measured by portion of lower incisor covered by upper central incisors when in occlusion)

- Horizontal overjet (measured between the labial surface of upper incisor to labial surface of lower incisor)

Occlusal Feature Index recognises malocclusion is a combination of the way teeth occlude as well as the position of the teeth relative to the neighbouring teeth. However, the scoring system is not sensitive enough for case selection for orthodontic purposes.

Malocclusion Severity Estimate (MSE)

Introduced in 1961 by Grainger. MSE measured 7 weighted and defined measurement:[49]

- Overjet

- Overbite

- Anterior open bite

- Congenitally missing maxillary incisors

- First permanent molar relationship

- Posterior cross bite

- Tooth displacement (actual and potential)

MSE defined and outlined 6 syndromes of malocclusion:[49]

- Positive overjet and anterior open bite

- Positive overjet, positive overbite, distal molar relationship and posterior crossbite with maxillary teeth buccal to mandibular teeth.

- Negative overjet, mesial molar relationship and posterior crossbite with maxillary teeth lingual to mandibular teeth

- Congenitally missing maxillary incisors

- Tooth displacement

- Potential tooth displacement

Despite being a relative comprehensive definition, there are a few shortcomings of this index, namely: the data is derived from a 12 years old patients hence might not be valid for deciduous and mixed dentitions, the score does not reflect all the measurement that were taken and accumulated and the absence of any occlusal disorder is not scored as zero. Grainger then revised the MSE index and published the revised version in 1967 and renamed the index to Treatment Priority Index (TPI).[49]

Occlusal Index (OI)

Occlusal Index was developed by Summers in his doctoral dissertation in 1966, and the final paper was published in 1971. Based on Malocclusion Severity Estimate (MSE), OI attempted to overcome shortcoming of the MSE.[49]

Summers devised different scoring scheme for deciduous, mixed and permanent dentition with 6 predefined stages of dental age:[58]

- Dental age 0 begins at birth, ending with eruption of first deciduous tooth.

- Dental age 1 begins when stage 0 ended, ending with all deciduous teeth are in occlusion.

- Dental age 2 begins when stage 1 ended, ends with eruption of first permanent tooth.

- Dental age 3 begins when stage 2 ended and ends with all the permanent central, lateral incisors and first permanent molar are in occlusion.

- Dental age 4 begins when stage 3 ended and ends with eruption of any permanent canines or premolar.

- Dental age 5 begins when stage 4 ended and ends with all permanent canines and premolar are in occlusion.

- Dental age 6 begins when all permanent canines and premolar are in occlusion.

Nine weighted and defined measurement being taken:[49]

- Molar relation

- Overbite

- Overjet

- Posterior crossbite

- Posterior open bite

- Tooth displacement

- Midline relation

- Maxillary median diastema

- Congenitally missing maxillary incisors

Summers also defined 7 malocclusion syndromes which includes:[58]

- Overjet and openbite

- Distal molar relation, overbite, overjet, posterior crossbite, midline diastema and midline deviation

- Congenitally missing maxillary incisors

- Tooth displacement (actual and potential)

- Posterior open bite

- Mesial molar relation, overjet, overbite, posterior crossbite, midline diastema and midline deviation

- Mesial molar relation, mixed dentition analysis (potential tooth displacement) and tooth displacement.

Grade Index Scale for Assessment of Treatment Need (GISATIN)

Grade Index Scale for assessment of treatment need (GISATN) was created by Salonen L in 1966. GISATN grades the type and severity of the malocclusion however the index doesn’t indicate or describe the damage each type of occlusion can cause.[59]

Treatment Priority Index (TPI)

Treatment priority index (TPI) was created in 1967 by R.M. Grainger in Washington D.C United states.[60] Grainger described the index as “a method of assessing the severity of the most common types of malocclusion, the degree of handicaps or their priority of treatment”. In the index there are eleven weighed and defined measurements which are: upper anterior segment overjet, lower anterior segment overjet, overbite of upper anterior over lower anterior, anterior open bite, congenital absence of incisors, distal molar relation, mesial molar relation, posterior cross bite (buccal), posterior cross bite (lingual), tooth displacement, gross anomalies. It also includes the seven maloclussion syndromes: maxillary expansion syndrome, overbite, retrognathism, open bite, prognathism, maxillary collapse syndrome and congenitally missing incisors.[61]

Handicapping Malocclusion Assessment Record (HMAR)

Handicapping malocclusion assessment record (HMAR) was created by Salzmann JA in 1968. It was created to establish needs for treatment of handicapping malocclusion according to severity presented by magnitude of the score when assessing the malocclusion.[62] The assessment can be made either directly from the oral cavity or from available casts. To make the assessment more accurate an additional record form is made for direct mouth assessment which allows the recording and scoring of mandibular function, facial asymmetry, lower lip malposition in relation to the maxillary incisor teeth and desirability of treatment.[62] The index has been accepted as a standard by the Council or Orthodontic Health Care, the Board of Directors of the American Association due to the easy use of HMAR.[63]

Littles Irregularity Index

Little irregularity index was first written about in his published paper The Irregularity Index: a quantitative score of mandibular anterior alignment.[64] The Littles Irregularity index is generally used by public health sectors and insurance companies to determine the need for treatment and the severity of the malocclusion. It is said that the method is “simple, reliable and valid” of which to measure linear displacement of the tooths contact point. The index is used by creating five linear lines of adjacent contact points starting from mesial of right canine to mesial of left canine and this is recorded. Once this is done the model cast can be ranked on a scale ranging from 0-10.[65]

WHO/FDI - basic method for recording of malocclusion

The WHO/FDI index uses the prevalence of malocclusion ion and estimates the needs for treatment of the population by various ways. It was developed by the Federation Dentaire Internationale (FDI) Commission on Classification and Statistics for Oral Conditions (COCSTOC). The aim when creating the index was to allow for a system in measuring occlusion which can be easily comparable. The five major groups which are recorded are as follows: 1.Gross Anomalies 2.Dentition: absent teeth, supernumerary teeth, malformed incisors and exotic eruption 3.Spaced condition: Diastema, Crowding and Spacing 4.Occlusion:

* Incisor segment : maxillary /mandicular overjet, overbite, open bite and cross bite

* Lateral segment: anteroposterior relations, open bite, posterior cross bite

5. Orthodontic treatment need judged subjectively : non necessary, doubtful and necessary [66]

Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI)

The aesthetic index created in 1986 by Cons NC and Jenny J and has been recognised by WHO by which it was added into the International Collaboration Study of Oral health Outcomes. The index links the aesthetic aspect and the clinical need plus the patients perception and combines them mathematically to produce a single score.[67] Even though DAI is widely recognised in the USA, in Europe due to government pressures more effort was spent on defining patients with malocclusions which can be damaging and which can qualify under the government regulations to be paid for rather than looking at the aesthetic aspect.[68]

Handicapping Labiollingual Deviation (HLD) (CalMOD)

HLD was a suggestion by Dr. Harry L. Draker in 1960 in the published American Journal of Orthodontics in 1960. It was meant to identify the most unfavourable looking malocclusion as handicapping however it completely failed to recognise patients with a large maxillary protrusion with fairly even teeth, which would be seen extremely handicapped by the public. The index finally became a law driven modification of the 1960 suggestion by Dr. Harry L. Draker and became the HLD (CalMod) Index of California. In 1994, California was sued once again and the settlement from this allowed for adjustments to be made. This allowed overjets greater than 9mm to qualify as an exception, correcting the failure of the previous modification. To settle the suit and respond to plaintiff’s wishes a reverse overate greater than 3.5mm was also included into the qualifying exception. The modification later went into official use in 1991.[69]

The intent of the HLD (CalMod) index is measuring the presence or absence, and the degree of the handicap caused by components of the index and not to diagnose malocclusion. The measurements for the index are made with a Boley Gauge (or a disposable ruler) scaled in millimetres. Absence of a condition must be presented by entering ‘0’.

These are the various conditions you have to take into consideration:

- Cleft palata deformities

- Deep impinging overbite

- Cross bite of individual anterior teeth

- Severe traumatic deviations

- Overjet greater than 9mm

- Overjet in mm

- Overbite in mm

- Mandibular protrusion in mm

- Open bite in mm

- Ectopic eruption

- Anterior crowding

- Labiolingual spread

- Posterior unilateral Crossbite

Once this is completed and all the checks are done, the scores are added up. If the patient does not score 26 or above they may still be eligible under the EPSDT (Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment) exception, if medical necessity is documented.[70]

Peer Assessment Rating Index (PAR)

This index was implemented in 1987 by the British Orthodontic Standard Working Party after 10 members of this party formulated this index over a series of 6 meetings[71]

This index is a fast, simple and robust way of assessing the standard of orthodontic treatment that an individual orthodontist is achieving or trying to achieve rather than the degree of malocclusion and/or need for orthodontic treatment. However, it should have already been concluded that these patients should be receiving orthodontic treatment prior to the PAR index. The PAR index has also been used to assess whether clinicians are correctly determining the need for orthodontic treatment when compared with a calibrated examiner of malocclusion.[71]

This type of index compares outcomes of orthodontic treatment as it primarily observes the results of a group of patients, rather than on an individual basis against results that they would expect. This type of testing occurs as there will always be a small number of individual patients in which the index results does not fully represent.[72] The interpretation of the results shows that when there is a PAR score of more than 70% it represents a very high standard of treatment, anything less than 50% shows an overall poor standard of treatment and below 30% means that the patients malocclusion has not been improved by orthodontic treatment[73]

The results should only be compared using a group of patients rather than individual bases as this could show completely different results which wouldn't be representative of the standard of treatment being carried out[74]

Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN)

The Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need was developed and tested in 1989 by Brook and Shaw in England following a government initiative.[75]

The aim of the IOTN is to assess the probable impact a malocclusion may have on an individual’s dental health and psychosocial wellbeing.[76] The index easily identifies the individuals who will benefit most from orthodontic treatment and assigns them a treatment priority. Hence, in the UK, it is used to determine whether a patient under the age of 18 years is eligible for orthodontic treatment on the NHS.

It comprises two elements: the dental health component and an aesthetic component.[77]

For the dental health component (DHC), malocclusion is categorised into 5 grades based on occlusal characteristics that could affect the function and longevity of the dentition. The index is not cumulative; the single worst feature of a malocclusion determines the grade assigned.[76]

| Dental health component of the IOTN |

|---|

| Grade 5 (treatment required) |

| 5.a Increased overjet >9mm

5.h Extensive hypodontia with restorative implications (more than one tooth missing in any quadrant requiring pre-restorative orthodontics) 5.i Impeded eruption of teeth (apart from 3rd molars) due to crowding, displacement, the presence of supernumerary teeth, retained deciduous teeth, and any pathological cause 5.m Reverse overjet >3.5mm with reported masticatory and speech difficulties 5.p Defects of cleft lip and palate 5.s Submerged deciduous teeth |

| Grade 4 (treatment required) |

| 4.a Increased overjet >6mm but ≤9mm

4.b Reverse overjet >3.5mm with no masticatory or speech difficulties 4.c Anterior or posterior crossbites with >2mm discrepancy between the retruded contact position and intercuspal position 4.d Severe displacements of teeth >4 4.e Extreme lateral or anterior open bites >4mm 4.f Increased and complete overbite with gingival or palatal trauma 4.g Less extensive hypodontia requiring pre-restorative orthodontics or orthodontic space closure to obviate the need for a prosthesis 4.h Posterior lingual crossbite with no functional occlusal contact in one or more buccal segments 4.i Reverse overjet >1mm but <3.5mm with recorded masticatory and speech difficulties 4.j Partially erupted teeth, tipped and impacted against adjacent teeth 4.k Existing supernumerary teeth |

| Grade 3 (borderline/moderate need) |

| 3.a Increased overjet >3.5mm but ≤6mm (incompetent lips)

3.b Reverse overjet greater than 1 mm but ≤3.5mm 3.c Anterior or posterior crossbites with >1mm but ≤2mm discrepancy between the retruded contact position and intercuspal position 3.d Displacement of teeth >2mm but ≤4mm 3.e Lateral or anterior open bite >2mm but ≤4mm 3.f Increased and incomplete overbite without gingival or palatal trauma |

| Grade 2 (little treatment need) |

| 2.a Increased Overjet >3.5 mm but ≤6 mm (with competent lips)

2.b Reverse overjet greater than 0 mm but ≤1mm 2.c Anterior or posterior crossbite with ≤1mm discrepancy between retruded contact position and intercuspal position 2.d Displacement of teeth >1mm but ≤2mm 2.e Anterior or posterior open bite >1mm but ≤2mm 2.f Increased overbite ≥3.5mm (without gingival contact) 2.g Pre normal or post normal occlusions with no other anomalies. Includes up to half a unit discrepancy |

| Grade 1 (no treatment required) |

| 1. Extremely minor malocclusions, including displacements less than 1mm [75] |

The aesthetic component (AC) takes into consideration the potential psychosocial impact of a malocclusion. A scale of 10 standardised colour photographs showing decreasing levels of dental attractiveness is used. The pictures are compared to the patient’s teeth, when viewed in occlusion from the anterior aspect, by an orthodontist who will score accordingly. The scores are categorised according to treatment need:

- Score 1 or 2 – no need

- Score 3 or 4 – slight need

- Score 5, 6, or 7 – moderate/borderline

- Score 8, 9, or 10 – definite need[76]

The AC has been criticised due to its subjective nature and for the lack of representation of Class III malocclusions and anterior open bites in the photographs used.

Often, the DHC score alone is used to determine treatment need. However, the AC is often used in borderline cases (DHC grade 3).[76] The IOTN is used in the following manner:

| Grading | Treatment Required | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| DHC 1 | No NHS orthodontic treatment | Lack of health benefit due to almost perfect occlusion |

| DHC 2 | No NHS orthodontic treatment | Lack of health benefit as patient has minor occlusion irregularities |

| DHC 3 and AC 1-5 | Normally no NHS orthodontic treatment unless there are exceptional circumstances* | Lack of health benefit even though there are greater irregularities.

*patient with a Class II Division 2 malocclusion with traumatic over bite |

| DHC 3 and AC 6-10, or DHC 4-5 | Eligible for NHS orthodontic treatment | More severe degree of irregularity to severe dental health problems |

Memorandum of Orthodontic Screen and Indication for Orthodontic Treatment

This index was implemented in 1990 by Danish national board of health.[79]

In 1990 a Danish system was introduced based on health risks related to malocclusion, where it describes possible damages and problems arising from untreated malocclusion which allows for the identification of treatment need.

This mandate introduced a descriptive index that is more valid from a biological view, using qualitative analysis instead of a quantitative.[80]

Ideal Tooth Relationship Index

The ITRI was established in 1992 by Haeger which utilises both intra-arch and inter-arch relationships to generate index scores to compare the entire dentitions occlusion. This index is of use as it divides the arches into segments which would result in a more accurate outcome.[81][82]

This index evaluates tooth relationships from a morphological perspective which has been of use when evaluating the results of orthodontic treatment, post-treatment stability, settling, relapse and different orthodontic treatment modalities.[83]

The ITRI can allow for comparisons to be made in an objective and quantitative manner that allows for statistical analysis of orthodontic outcomes.[81]

Need for Orthodontic Treatment Index (NOTI)

This index was first described and implemented in 1992 by Espeland LV et al and is also known as the Norwegian Orthodontic Treatment Index.[84]

This index is used by the Norwegian health insurance system and due to this it is designed for allocation of public subsidies of treatment expenses, and the amount of reimbursement which is related to the category of treatment need. It classifies malocclusions into four categories based on the necessity of the treatment need.[85]

Risk of Malocclusion Assessment (ROMA)

This is a tool used to assess treatment need in young patients by evaluating malocclusion problems in growing children, assuming that some aspects may change under positive or negative effects of craniofacial development. It was published for use in 1998 by Russo et al.

This index illustrates the need for orthodontic intervention and is used to establish a relationship between the registered onset of orthodontic treatment and disorders inhibiting growth of facial and alveolar bones, and the development of the dentition along with the IOTN index.[86]

This index can be used in exchange for the IOTN scale as it is quick and easy to apply as a screening test to decide whether and when to refer patients to specialist orthodontists.

Index of Complexity, Outcome and Need (ICON)

This index was produced in 2000 by Charles Daniels and Stephen Richmond in Cardiff and has been investigated to illustrate that it can be used to replace the PAR and IOTN scale as a means of determining need and outcome of orthodontic treatment.[87]

This index measures the following to produce a scoring system:

- Dental aesthetics as measured by the aesthetic component of the IOTN

- The presence of a cross bite

- Anterior vertical relationship as measured by PAR

- Upper arch crowding/spacing on a 5 point scale

- Buccal segment Antero-posterior relationship as measured by PAR.[87]

The measurements are added together to produce a score which can be interpreted by score ranges that give need for treatment, complexity and degree of improvement.

This system claims to be more efficient than the PAR and IOTN indices as it only requires a single measurement protocol but this has still to be validated to be used in the UK and the issue that It does not suitably predict appearance, function, speech or treatment need for individuals attending general dental practice for routine dental treatment, so for these reasons is it generally never used.[88][89]

Baby-ROMA

This was established in 2014 by Grippaudo et al for use in assessing the risks/benefits of early orthodontic therapies in the primary dentition.

It is a paediatric type version of the ROMA scale. It measures occlusal parameters, skeletal and functional factors that may represent negative risks for a physiological development of the orofacial region, and indicates the need for preventative or interceptions orthodontic treatment using a score scale.[90]

This index was designed as it has been observed that some of the malocclusion signs observed in the primary dentition can deteriorate with growth while others remain the same over time and others can even improve. This index is therefore used to classify the malocclusions observed at an early stage on a risk based scale.

Training

There are several specialty areas in dentistry, but the specialty of orthodontics was the first to be recognized within dentistry.[91] Specifically, the American Dental Association recognized orthodontics as a specialty in the 1950s.[91] Each country has their own system for training and registering orthodontic specialists.

Canada

In Canada, obtaining a dental degree, such as a Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) or Doctor of Medical Dentistry (DMD), would be required before being accepted by a school for orthodontic training.[92] Currently, there are 10 schools in the country offering the orthodontic specialty.[92] Candidates should contact the individual school directly to obtain the most recent pre-requisites before entry.[92] The Canadian Dental Association expects orthodontists to complete at least two years of post-doctoral, specialty training in orthodontics in an accredited program, after graduating from their dental degree.

United States

Similar to Canada, there are several colleges and universities in the United States that offer orthodontic programs. Every school has a different enrollment process, but every applicant is required to have graduated with a DDS or DMD from an accredited dental school.[93][94] Entrance into an accredited orthodontics program is extremely competitive, and begins by passing a national or state licensing exam.[95]

The program generally lasts for two to three years, and by the final year, graduates are to complete the written American Board of Orthodontics (ABO) exam.[95] This exam is also broken down into two components: a written exam and a clinical exam.[95] The written exam is a comprehensive exam that tests for the applicant’s knowledge of basic sciences and clinical concepts.[95] The clinical exam, however, consists of a Board Case Oral Examination (BCOE), a Case Report Examination (CRE), and a Case Report Oral Examination (CROE).[95] Once certified, certification must then be renewed every ten years.[95] Orthodontic programs can award the Master of Science degree, Doctor of Science degree, or Doctor of Philosophy degree depending on the school and individual research requirements.[96]

Bangladesh

Dhaka Dental College in Bangladesh is one of the many schools recognized by the Bangladesh Medical and Dental Council (BM&DC) that offer post-graduation orthodontic courses.[97][98] Before applying to any post-graduation training courses, an applicant must have completed the Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) examination from any dental college.[97] After application, the applicant must take an admissions test held by the specific college.[97] When successful, selected candidates undergo training for six months.[99]

United Kingdom

Throughout the United Kingdom, there are several Orthodontic Specialty Training Registrar posts available.[100] The program is full-time for three years, and upon completion, trainees graduate with a degree at the Masters or Doctorate level.[100] Training may take place within hospital departments that are linked to recognized dental schools.[100] Obtaining a Certificate of Completion of Specialty Training (CCST) allows an orthodontic specialist to be registered under the General Dental Council (GDC).[100] An orthodontic specialist can provide care within a primary care setting, but to work at a hospital as an orthodontic consultant, higher level training is further required as a post-CCST trainee.[100] To work within a university setting, as an academic consultant, completing research toward obtaining a PhD is also required.[100]

Pakistan

In Pakistan to be enrolled as a student or resident in postgraduation orthodontic course approved by Pakistan medical and dental council, the dentist must graduate with a Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) or equivalent degree. Pakistan Medical & Dental Council (PMDC) has a recognized program in orthodontics as Master in Dental Surgery (MDS) orthodontics and FCPS orthodontics as 4 years post graduation degree programs, latter of which is conducted by CPSP Pakistan.

Oral hygiene and care of orthodontic appliances

Good oral hygiene is essential for successful orthodontic treatment.[101] The presence of orthodontic appliances placed on the teeth makes traditional oral home care techniques very challenging to perform. It is important that a good oral hygiene regime is established at the beginning of treatment and adhered to. A lapse in this may lead to a common complication of orthodontic treatment - tooth decay and periodontal disease.[102]

The earliest sign of tooth decay that can be detected with the naked eye is the presence of white spot lesions. These can occur as early as 4 weeks after treatment with an appliance commences.[103] It is therefore important to ensure that all surfaces of the tooth’s crown are reached to ensure effective plaque removal. The places with the highest level of plaque accumulation for someone with an orthodontic appliance is around the maxillary lateral incisors and canines, gingival margin and appliance brackets. Regular toothbrushes may struggle to reach all these places therefore providing inadequate cleaning. A toothbrush that is regularly replaced, Interdental brushes and floss are helpful in achieving this.[104]

Orthodontists recommend that those currently undergoing orthodontic treatment brush twice daily with a fluoride toothpaste – one containing 2,800ppm of NaF is indicated for those with orthodontic appliances. It is also recommended that patients also use fluoride mouth rinse at a separate time to brushing.[105]

Diet is also an important part of establishing a good oral health regimen. Avoiding crunchy and sticky foods will not only reduce the level of food deposits around the appliance but also protect the delicate wires and brackets against breakage and separation. Reducing the level of sugar in the diet also decreases the risk of caries, that can lead to demineralisation around the appliance. Limiting high sugar food and drink to meal times is an effective way of doing this. In between meals snacking on healthy foods such as wholemeal bread, dry crackers, bread sticks vegetables sticks and cheese. These are all safe food and will help to reduce the risk of forming caries. Be aware eating hard or chewy foods such as apples and carrots can lead to wire breakages, cut these foods up first or avoid them completely for the duration of treatment.[106]

When wearing a removable appliance, a high quality of care is equally important. After each meal the appliance should be removed, and the teeth cleaned as normal. The toothbrush and paste should then be used to gently brush away any food or plaque deposits from the appliance, over a bowl of water to prevent breakage if dropped. It is ideal for patients to carry a tooth brush with them during treatment to allow this level of cleaning to take place while at school or work.[107]

See also

References

- ↑ "orthodontics".. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ Milton B. Asbell; Cherry Hill; N. J. (August 1990). "A brief history of orthodontics". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 98 (2): 176–183. doi:10.1016/0889-5406(90)70012-2. PMID 2198802.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Orthodontic Braces - ArchWired". www.archwired.com.

- ↑ McLain JB; Proffit WR (June 1985). "Oral health status in the United States: prevalence of malocclusion". Journal of Dental Education. 49 (6): 386–397. PMID 3859517.

- ↑ Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi-Farahani A, Eslamipour F (October 2009). "Malocclusion and occlusal traits in an urban Iranian population. An epidemiological study of 11- to 14-year-old children". European Journal of Orthodontics. 31 (5): 477–484. doi:10.1093/ejo/cjp031. PMID 19477970.

- ↑ Borzabadi-Farahani A. (October 2009). "An insight into four orthodontic treatment need indices". Progress in Orthodontics. 12 (2): 132–142. doi:10.1016/j.pio.2011.06.001. PMID 22074838.

- ↑ Borzabadi-Farahani, A, Borzabadi-Farahani, A (August 2011). "Agreement between the index of complexity, outcome, components of the index of orthodontic treatment need". Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 140 (2): 233–238. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.09.028. PMID 21803261.

- ↑ Borzabadi-Farahani, Ali (2011). "An Overview of Selected Orthodontic Treatment Need Indices". In Naretto, Silvano. Principles in Contemporary Orthodontics. In Tech. pp. 215–236. doi:10.5772/19735. ISBN 978-953-307-687-4.

- ↑ Akram A, McKnight MM, Bellardie H, Beale V, Evans RD (February 2015). "Craniofacial malformations and the orthodontist". Br Dent J. 218 (3): 129–41. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.48. PMID 25686430.

- ↑ Pedro E. Santiago; Barry H. Grayson. (February 2009). "Role of the Craniofacial Orthodontist on the Craniofacial and Cleft Lip and Palate Team". Seminars in Orthodontics. 15 (4): 225–243. doi:10.1053/j.sodo.2009.07.004.

- ↑ Joseph G. McCarthy (February 2009). "Development of Craniofacial Orthodontics as a Subspecialty at New York University Medical Center". Seminars in Orthodontics. 15 (4): 221–224. doi:10.1053/j.sodo.2009.07.003.

- ↑ ADA Accredited programs in Craniofacial and Special Care Orthodontics, Retrieved March 8, 2015, from ADA: American Dental Association: https://www.aaoinfo.org/sites/default/files/community_docs/ADA%20Accredited%20programs%20in%20Craniofacial%20and%20Special%20Care%20Orthodontics.pdf

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010572.pub2/full"

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003452.pub3/full

- ↑ "Child Dental Health Survey 2013, England, Wales and Northern Ireland". digital.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- ↑ Mitchell, Laura (2013). An Introduction to Orthodontics. Oxford Medical Publications. pp. 220–233.

- ↑ "https://www.bos.org.uk/Public-Patients/Orthodontics-for-Children-Teens/Treatment-brace-types/Removable-appliances/Functional-appliances"

- ↑ Rome. "Ultimate Braces Guide". Orthodontist National Directory. July 6, 2017.

- ↑ ""

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007859.pub3/full

- ↑ "https://www.bos.org.uk/Public-Patients/Orthodontics-for-Children-Teens/Treatment-brace-types/Fixed-appliances/Conventional"

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005516.pub2/abstract"

- ↑ ""

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005098.pub3/full"

- 1 2 "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003451.pub2/full"

- ↑ ","

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006204.pub3/full

- ↑ "https://www.bos.org.uk/Public-Patients/Orthodontics-for-Children-Teens/Treatment-brace-types/Orthognathic-treatment-surgery"

- 1 2 ""

- 1 2 3 "Luther, F. A. & Nelson-Moon, Z. A. Removable orthodontic appliances and retainers : principles of design and use"

- ↑ ""

- ↑ "https://www.bos.org.uk/Public-Patients/Orthodontics-for-Children-Teens/Treatment-brace-types/Removable-appliances/Clear-aligners"

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010572.pub2/full

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010887.pub2/full"

- ↑ ""

- 1 2 "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD002283.pub4/full"

- ↑ "http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008734.pub2/full"

- ↑ T. M. Graber, R.L. Vanarsdall, Orthodontics, Current Principles and Techniques, "Diagnosis and Treatment Planning in Orthodontics", D. M. Sarver, W.R. Proffit, J. L. Ackerman, Mosby, 2000

- 1 2 Mitchell, L. (2013). An introduction to orthodontics. 4th ed. Oxford University Press, p.86

- ↑ Mitchell, L. (2013). An introduction to orthodontics. 4th ed. Oxford University Press, pp.88-89

- 1 2 Mitchell, L. (2013). An introduction to orthodontics. 4th ed. Oxford University Press, p.91

- ↑ Mitchell, L. (2013). An introduction to orthodontics. 4th ed. Oxford University Press, p.95

- 1 2 Heasman, Peter (2013). Master Dentistry Volume Two (Third ed.). Elsevier Limited.

- 1 2 1958-, Mitchell, Laura, (2013). An introduction to orthodontics. Littlewood, Simon J.,, Nelson-Moon, Zararna,, Dyer, Fiona, (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191003035. OCLC 854583725.

- 1 2 3 Mitchell, Laura (2013). An Introduction to Orthodontics (Fourth ed.). Oxford Medical Publications.

- ↑ http://www.jaypeejournals.com/eJournals/ShowText.aspx?ID=2695&Type=FREE&TYP=TOP&IN=_eJournals/images/JPLOGO.gif&IID=212&isPDF=YES

- ↑ "Angle's Classification of Malocclusion". Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- 1 2 3 HUMMEL, C. F. The Angle Classification, Does it Mean Anything to Orthodontists Today?*. https://dx.doi.org/10.1043/0003-3219(1934)0042.0.CO;2, 2009-07-15 2009. Disponível em: < http://www.angle.org/doi/abs/10.1043/0003-3219(1934)004%3C0057:TACDIM%3E2.0.CO%3B2 >

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tang, EL; Wei, SH (April 1993). "Recording and measuring malocclusion: a review of the literature". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics : Official Publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its Constituent Societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 103 (4): 344–51. doi:10.1016/0889-5406(93)70015-G. PMID 8480700.

- ↑ "An Overview of Orthodontic Indices".

- 1 2 MASSLER, M.; FRANKEL, J. M. Prevalence of malocclusion in children aged 14 to 18 years. American Journal of Orthodontics, v. 37, n. 10, p. 751-768, 1951/10/01 1951. ISSN 0002-9416. Disponível em: < http://www.ajodo.org/article/0002941651900474/abstract >.Disponível em: < http://www.ajodo.org/article/0002941651900474/fulltext >.Disponível em: < http://www.ajodo.org/article/0002941651900474/pdf >.

- ↑ OTUYEMI, O. D.; JONES, S. P. Methods of assessing and grading malocclusion: a review. Aust Orthod J, v. 14, n. 1, p. 21-7, Oct 1995. ISSN 0587-3908 (Print)0587-3908. Disponível em: < https://dx.doi.org/ >.

- 1 2 3 Vankirk, Lawrence. "Assessment of malocclusion in population groups". American Journal of Orthodontics. 45 (10): 752–758.

- ↑ Draker, Harry L. "Handicapping labio-lingual deviations: A proposed index for public health purposes". American Journal of Orthodontics. 46 (4): 295–305.

- ↑ Han, H; Davidson, WM (September 2001). "A useful insight into 2 occlusal indexes: HLD(Md) and HLD(CalMod)". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics : Official Publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its Constituent Societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 120 (3): 247–53. doi:10.1067/mod.2001.118104. PMID 11552123.

- ↑ Theis, JE; Huang, GJ; King, GJ; Omnell, ML (December 2005). "Eligibility for publicly funded orthodontic treatment determined by the handicapping labiolingual deviation index". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics : Official Publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its Constituent Societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 128 (6): 708–15. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.10.012. PMID 16360910.

- 1 2 Poulton, Donald R.; Aaronson, Sanford A. (1 September 1961). "The relationship between occlusion and periodontal status". American Journal of Orthodontics. 47 (9): 690–699. doi:10.1016/0002-9416(61)90112-9. ISSN 0002-9416.

- 1 2 Summers, CJ (June 1971). "The occlusal index: a system for identifying and scoring occlusal disorders". American Journal of Orthodontics. 59 (6): 552–67. PMID 5280423.

- ↑ Grippaudo, Cristina (2008). 5. p. 181. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Grainger, R.M. (Dec 1967). "Orthodontic treatment priority index". National Centre for Health Statistics. 25 (Series 2).

- ↑ Gupta, Alka; Man Shrestha, Rabindra (Dec 2014). "A Review of Orthodontic Indices". Journal of Nepal Review. 4 (2): 47.

- 1 2 Salzmann, J.A. (Oct 1968). Handicapping malocclusions assessment to establish treatment priority (54th ed.). p. 749–750.

- ↑ Otuyemi, O.D.; Near, J.H. (18 Aug 1995). "Variability in recording and grading the need for orthodontic treatment using the handicapping malocclusion assessment record". Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology: 222.

- ↑ Little, Robert M (1975). "The Irregularity Index: A quantitive score of mandibular anterior alignment". American Journal of Orthodontics.

- ↑ Gupta, Alka; Sgrestha, Rabindra Man (Dec 2014). "A Review of Orthodontic Indices Review". Orthodontic Journal of Nepal. 4 (2): 48.

- ↑ Gupta, Alka; Shrestha, Rabindra Man (Dec 2014). "A Review of Orthodontic Indices". Orthodontic Journal of Nepal. 4: 46.

- ↑ Gupta, Alka; Shrestha, Rabindra Man (Dec 2014). "A Review of Orthodontic Indices". Orthodontic Journal of Nepal. 4: 48.

- ↑ Parker, William S (Aug 1998). "The HLD (CalMod) index and the index question". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 114: 135.

- ↑ Parker, William S (Aug 1998). "The HLD (CalMod) index and the index question". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 114: 136.

- ↑ Parker, William S (Aug 1998). "The HLD (CalMod) index and the index question". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 114: 138, 139.

- 1 2 Richmond, S.; Shaw, W. C.; O'Brien, K. D.; Buchanan, I. B.; Jones, R.; Stephens, C. D.; Roberts, C. T.; Andrews, M. (April 1992). "The development of the PAR Index (Peer Assessment Rating): reliability and validity". European Journal of Orthodontics. 14 (2): 125–139. ISSN 0141-5387. PMID 1582457.

- ↑ "British Orthodontic Society > Professionals & Members > Research & Audit > Quality Assurance in Orthodontics > The Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) index". www.bos.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- ↑ NHS England (November 2013). "Transitional commissioning of primary care orthodontic services" (PDF). NHS England.

- ↑ Firestone, Allen R; Beck, F.Michael; Beglin, Frank M; Vig, Katherine W.L (2002-11-01). "Evaluation of the peer assessment rating (PAR) index as an index of orthodontic treatment need". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 122 (5): 463–469. doi:10.1067/mod.2002.128465. ISSN 0889-5406. PMID 12439473.

- 1 2 Brook, Peter H.; Shaw, William C. (1989-08-01). "The development of an index of orthodontic treatment priority". European Journal of Orthodontics. 11 (3): 309–320. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.651.8279. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejo.a035999. ISSN 0141-5387.

- 1 2 3 4 Mitchell, Laura (2014). An Introduction to Orthodontics. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

- ↑ "British Orthodontic Society > Public & Patients > Orthodontics for Children & Teens > Fact File & FAQ > What Is The IOTN?". www.bos.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- ↑ The Scottish Government (7 September 2011). "GENERAL DENTAL SERVICES ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT – INTRODUCTION OF INDEX OF ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT NEED" (PDF). WWW.Scottishdental.org.

- ↑ Grippaudo, Cristina; Paolantonio, Ester Giulia; Torre, Giuseppe La; Gualano, Maria Rosaria; Oliva, Bruno; Deli, Roberto (2012-05-15). "Comparing orthodontic treatment need indexes". Italian Journal of Public Health. 5 (3). doi:10.2427/5823. ISSN 1723-7815.

- ↑ "Danish National Board of Health". Memorandum of orthodontic screening and indications for orthodontic treatment. 1990.

- 1 2 Haeger, Robert S; Schneider, Bernard J; Begole, Ellen A (1992-05-01). "A static occlusal analysis based on ideal interarch and intraarch relationships". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 101 (5): 459–464. doi:10.1016/0889-5406(92)70120-Y. ISSN 0889-5406. PMID 1590295.

- ↑ Tahir, Ejaz; Sadowsky, Cyril; Schneider, Bernard J (1997-03-01). "An assessment of treatment outcome in American Board of Orthodontics cases". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 111 (3): 335–342. doi:10.1016/S0889-5406(97)70193-8. ISSN 0889-5406.

- ↑ Heiser, Wolfgang; Niederwanger, Andreas; Bancher, Beatrix; Bittermann, Gabriele; Neunteufel, Nikolaus; Kulmer, Siegfried (2004-08-01). "Three-dimensional dental arch and palatal form changes after extraction and nonextraction treatment. Part 1. Arch length and area". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics : Official Publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its Constituent Societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 126 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1016/S0889540604000885 (inactive 2018-08-30). PMID 15224062.

- ↑ Stenvik, A.; Espeland, L.; Berset, G. P.; Eriksen, H. M.; Zachrisson, B. U. (December 1996). "Need and desire for orthodontic (re-)treatment in 35-year-old Norwegians". Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics = Fortschritte der Kieferorthopadie: Organ/Official Journal Deutsche Gesellschaft Fur Kieferorthopadie. 57 (6): 334–342. ISSN 1434-5293. PMID 8986052.

- ↑ Ferro, R.; Besostri, A.; Denotti, G.; Campus, G. (September 2013). "Public community orthodontics in Italy. Description of an experience". European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry: Official Journal of European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry. 14 (3): 237–240. ISSN 1591-996X. PMID 24295011.

- ↑ Grippaudo, C.; Paolantonio, E. G.; Deli, R.; La Torre, G. (June 2008). "Orthodontic treatment need in the Italian child population". European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry: Official Journal of European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry. 9 (2): 71–75. ISSN 1591-996X. PMID 18605888.

- 1 2 Daniels, C.; Richmond, S. (June 2000). "The development of the index of complexity, outcome and need (ICON)". Journal of Orthodontics. 27 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1093/ortho/27.2.149. ISSN 1465-3125. PMID 10867071.

- ↑ Moss, J P (2001-09-22). "General practice: ICON and the patient's perceptions of malocclusion". BDJ. 191 (6): 316. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4801173.

- ↑ Fox, N A; Daniels, C; Gilgrass, T (2002-08-24). "A comparison of the Index of Complexity Outcome and Need (ICON) with the Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) and the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN)". British Dental Journal. 193 (4): 225–230. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4801530. ISSN 1476-5373.

- ↑ Grippaudo, C.; Paolantonio, E. G.; Pantanali, F.; Antonini, G.; Deli, R. (December 2014). "Early orthodontic treatment: a new index to assess the risk of malocclusion in primary dentition". European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry: Official Journal of European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry. 15 (4): 401–406. ISSN 1591-996X. PMID 25517589.

- 1 2 Christensen, Gordon J (March 2002). "Orthodontics and the general practitioner". The Journal of the American Dental Association. 133: 369–371.

- 1 2 3 "FAQ: I Want To Be An Orthodontist - Canadian Association of Orthodontists". Canadian Association of Orthodontists. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "RCDC - Eligibility". The Royal College of Dentists of Canada. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Accredited Orthodontic Programs - AAO Members". www.aaoinfo.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "About Board Certification". American Board of Orthodontists. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Accredited Orthodontic Programs | AAO Members". American Association of Orthodontists. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 [dhakadental.gov.bd "Dhaka Dental College"] Check

|url=value (help). Dhaka Dental College. Retrieved October 28, 2017. - ↑ [bmdc.org.bd "List of recognized medical and dental colleges"] Check

|url=value (help). Bangladesh Medical & Dental Council (BM&DC). Retrieved October 28, 2017. - ↑ "Orthodontic Facts - Canadian Association of Orthodontists". Canadian Association of Orthodontists. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 https://www.bos.org.uk/Portals/0/Public/docs/Careers/guidelines-on-orthodontic-specialty-training.pdf "Orthodontic Specialty Training in the UK" (PDF). British Orthodontic Society. British Orthodontic Society. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ Travess, H. (2004). "Orthodontics. Part 6: Risks in orthodontic treatment" (PDF). British Dental Journal. 196: 71–77.

- ↑ "Orthodontics". NHS Choices.

- ↑ Srivastava, Kamna (April 2013). "Risk factors and management of white spot lesions in orthodontics". Journal of Orthodontic Science. 2 (2): 43–49. doi:10.4103/2278-0203.115081. PMC 4072374. PMID 24987641.

- ↑ "How to Keep Your Teeth and Gums Healthy" (PDF). British Orthodontic Society. December 2008.

- ↑ "Delivering Better Oral Health" (PDF). Public Health England. March 2017.

- ↑ "Teeth and Brace Friendly Food and Drink" (PDF). British Orthodontic Society. April 2017.

- ↑ "Removable Appliances" (PDF). British Orthodontic Society. January 2012.

External links

| Look up orthodontics in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orthodontics. |