Ticsani

| Ticsani | |

|---|---|

The Ticsani lava dome complex (center) | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,408 m (17,743 ft) [1] |

| Coordinates | 16°45′18″S 70°35′42″W / 16.755°S 70.595°WCoordinates: 16°45′18″S 70°35′42″W / 16.755°S 70.595°W [1] |

| Geography | |

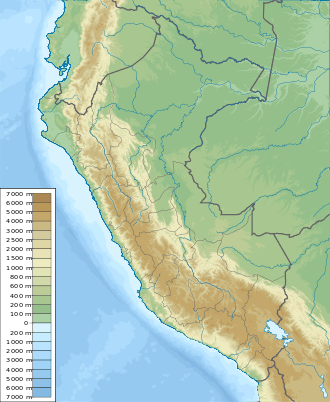

Ticsani Peru | |

| Location | Moquegua Region |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Lava domes |

| Last eruption | 1800 ± 200 years[1] |

Ticsani is a volcano in Peru. It consists of two volcanoes that form a complex: "old Ticsani", which is a compound volcano that underwent a large collapse in the past and shed 15–30 cubic kilometres (3.6–7.2 cu mi) of mass down the Rio Tambo valley; the other is a complex of three lava domes which were emplaced during the Holocene. The last eruption occurred after the 1600 eruption of neighbouring Huaynaputina.

Geography and geomorphology

Ticsani is in the Ichuna District of Peru,[1] 59 kilometres (37 mi) northwest of Moquegua.[2] The Putina River passes northwest and the Carumas River southwest of the volcano.[3] The area is remote, which has hampered exploration efforts.[4]

Volcanism in South America occurs along its western coast and in several volcanic belts, including the Central Volcanic Zone that Ticsani is part of. In southern Peru the Central Volcanic Zone includes the volcanoes Solimana, Coropuna, Ampato, Sabancaya, Chachani, El Misti, Ubinas, Huaynaputina, Ticsani, Tutupaca, Calientes, Yucamane, Purupuruni and Casiri.[5]

Ticsani features three lava domes, which were generated by latest Pleistocene and Holocene activity;[6] two of which are located within or at the margins of craters.[7] An earlier compound volcano is today preserved as a 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) long arcuate ridge,[6] which is northeast of the northernmost dome and opens to the west; a cryptodome is exposed within the arcuate ridge.[3] The complex reaches a height of 5,408 metres (17,743 ft).[8] The position of the lava domes and the structure of the compound volcano were influenced by local fault systems.[9]

Geology

Off the southwestern coast of South America, the Nazca Plate subducts beneath the South America Plate[10] in the Peru-Chile Trench,[5] at a rate of 10.3 centimetres per year (4.1 in/year). This subduction process is responsible for the growth of the Andes and for volcanism in the region; the oblique character of subduction has further led to the onset of strike-slip faulting.[4]

Ticsani is grouped together with the neighbouring volcanoes Huaynaputina and Ubinas, given their tectonic context, which is unusual for Peruvian volcanoes and shared geochemical traits. Huaynaputina had a large eruption in 1600 and Ubinas is presently the most active volcano in southern Peru.[4] These volcanoes appear to share a magma chamber[11] at a depth of 20–30 kilometres (12–19 mi).[8]

The basement on which these volcanoes rose includes a Paleoproterozoic pluton. It is covered by the Mesozoic Yura Group and Matalaque Formation (sedimentary and volcanic rocks, respectively) which are exposed at the Rio Tambo. Volcanic activity continued during the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene, forming ignimbrites and the Barroso Group.[4]

Composition

The complex has erupted andesite during the compound volcano stage and dacite during the lava dome stage; both define a potassium-rich calc-alkaline suite.[12] Phenocrysts found in the later eruption products include amphibole, biotite, feldspar, plagioclase, pyroxene and quartz.[13]

Eruption history

Ticsani was active during the Pleistocene and Holocene.[4] At first, a compound volcano developed at Ticsani. This volcano collapsed and formed a landslide deposit in the Rio Tambo valley[6] which originally had a volume of about 15–30 cubic kilometres (3.6–7.2 cu mi),[14] and is thus the largest such collapse in southern Peru during the Pleistocene. This volcano stage is also known as "old Ticsani", separate from the lava dome associated "new Ticsani".[12]

Later three lava domes[lower-alpha 1] were emplaced and three explosive eruptions took place, accompanied by the emission of volcanic ash, blocks, lava bombs and pumice. The first eruption with a tephra volume of about 0.5 cubic kilometres (0.12 cu mi)[lower-alpha 2] happened at 10,600 ± 80 years before present, the second in the middle Holocene and the last sub-Plinian to phreatomagmatic eruption ("Brown Ticsani") took place shortly before the Huaynaputina eruption of 1600,[6] generating about 0.015 cubic kilometres (0.0036 cu mi) of tephra.[lower-alpha 3][16] This volcano stage also produced lava flows which filled valleys,[12] formed a lava flow field northwest of the volcano[1] and pyroclastic flows on the eastern side of the volcano.[14]

Presently, hot springs are found in the valleys west of Ticsani, and two fumaroles have been observed at its summit.[3] In 2005, earthquake activity was noted beneath Ticsani, possibly related to a hydrothermal system.[8] A temporary seismic station installed 2015 at Ticsani recorded volcano-tectonic earthquakes.[17]

Hazards

About 5,000 people live within 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) to Ticsani and would be threatened in the case of a future eruption, with particular hazards including ash fall, lahars, pyroclastic flows and the collapse of lava domes.[12] In addition to the local population, ashfall would hit major regional roads and reservoirs.[18]

In 2015, facilities to monitor the chemical composition of hot springs around the volcano were installed,[19] and devices to recognize deformations of the volcanic edifices are installed.[20] The Peruvian Southern Volcanological Observatory (Observatorio Vulcanológico del Sur) publishes monthly reports on Ticsani since 2014, which include reports on seismic activity and on sulfur dioxide emissions.[21]

Notes

- ↑ Sometimes four domes are counted, the fourth one east of the three canonical domes.[7]

- ↑ The eruption has been assigned a volcanic explosivity index of 4.[15]

- ↑ This eruption has been assigned a volcanic explosivity index of 2-3.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ticsani". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ INGEMMET 2015, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Byrdina et al. 2013, p. 154.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lavallée et al. 2009, p. 255.

- 1 2 Salazar & Thouret 2003, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 Lavallée et al. 2009, p. 257.

- 1 2 Salazar & Thouret 2003, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Byrdina et al. 2013, p. 153.

- ↑ Lavallée et al. 2009, p. 260.

- ↑ Lavallée et al. 2009, p. 254.

- ↑ Lavallée et al. 2009, p. 262.

- 1 2 3 4 Salazar & Thouret 2003, p. 2.

- ↑ Salazar & Thouret 2003, p. 17.

- 1 2 Salazar & Thouret 2003, p. 8.

- ↑ Salazar & Thouret 2003, p. 11.

- 1 2 Salazar & Thouret 2003, p. 12.

- ↑ INGEMMET 2015, p. 5.

- ↑ Salazar & Thouret 2003, p. 22.

- ↑ INGEMMET 2015, p. 18.

- ↑ INGEMMET 2015, p. 26.

- ↑ "Reportes del volcán Ticsani" (in Spanish). Southern Volcano Observatory. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

Sources

- Byrdina, S.; Ramos, D.; Vandemeulebrouck, J.; Masias, P.; Revil, A.; Finizola, A.; Gonzales Zuñiga, K.; Cruz, V.; Antayhua, Y.; Macedo, O. (March 2013). "Influence of the regional topography on the remote emplacement of hydrothermal systems with examples of Ticsani and Ubinas volcanoes, Southern Peru". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 365: 152–164. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2013.01.018. ISSN 0012-821X.

- INGEMMET (2015). "Monitoreo de los volcanes Coropuna, Ticsani y Tutupaca" (PDF) (in Spanish). Sistema de Información para la Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- Lavallée, Yan; de Silva, Shanaka L.; Salas, Guido; Byrnes, Jeffrey M. (October 2009). "Structural control on volcanism at the Ubinas, Huaynaputina, and Ticsani Volcanic Group (UHTVG), southern Peru". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 186 (3–4): 253–264. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.07.003. ISSN 0377-0273.

- Salazar, Jersy Mariño; Thouret, Jean-Claude (2003). "Geologıa, historia eruptiva y evaluación de peligros del volcán Ticsani" (PDF). Observatorio Vulcanológico del Sur (in Spanish). Sociedad Geológica del Perú. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

External links

- Pauccara, Vicentina Cruz (2006). "Caracterización geoquímica de las fuentes termales alrededor del volcán Ticsani Moquegua" (PDF). repositorio.ingemmet.gob.pe (in Spanish). Lima: 13th Peruvian Geological Congress. Retrieved 9 March 2018.