Spain–United Kingdom relations

| |

Spain |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

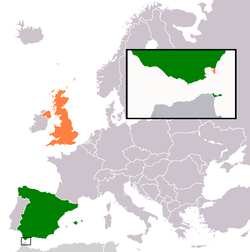

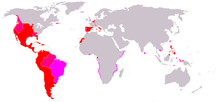

Spain–United Kingdom relations, also called Spanish-British relations, are the bilateral international relations between the Kingdom of Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

History

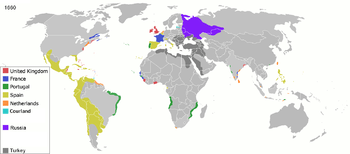

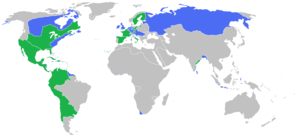

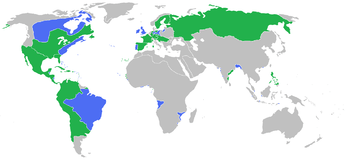

The history of Spanish–British relations is complicated by the political heritage of the two countries. Neither the United Kingdom nor Spain has a unique constitutional ancestor; the United Kingdom was originally created by a union of the kingdoms of England and Scotland (and later joined by Ireland), whilst the Kingdom of Spain was initially created by a union of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. They have also been complicated by the fact that the United Kingdom and Spain were both imperial powers, after the same land, an occurrence which is being played out to this day with the disputed ownership and status of Gibraltar.

Anglo-Portuguese Alliance

_(late_15th_C)%2C_f.244v_-_BL_Royal_MS_14_E_IV.png)

For centuries, the role of England, and subsequently the United Kingdom, in Iberia was coloured by the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance. Relations with Portugal always have been closer than those with Spain, and Spain and the United Kingdom have gone to war twice over Portugal's independence.

In 1384, at the height of the Hundred Years' War, England provided reinforcements to King João I to thwart a French-backed Castilian invasion. These forces saw action at the decisive battle of Aljubarrota, and proved to be vital in securing the continued independence of Portugal from its larger neighbours.

The alliance submerged into crisis when Portugal supported Joan of Castile instead of her aunt Isabella I of Castile during the War of the Castilian Succession of 1474–1479, because France also supported Joan's candidature. In the following years, the English collaborated with the Catholic Monarchs, there were weddings between English and Spanish heir princes and a small group of English soldiers even fought on the Castilian side during the conquest of Granada. However, the struggle of Elizabeth I of England against Philip II of Spain in the sixteenth century led to the new English support of the Portuguese independence movement that finished in 1640 with the crowning of King João IV of Portugal (not recognized by Spain until 1668). In following centuries, Portugal and the United Kingdom were closely allied in their politics and wars against Spain, which closely collaborated with France after the Spanish War of Succession (1700–1714) that established the House of Bourbon on the Spanish throne.

.svg.png)

Age of Exploration

Henry VIII of England, who had made a political match with Catherine of Aragon (a marriage that was later annulled by Henry), made a series of short-lived alliances with Carlos I against France during the Italian War of 1521 and the Italian War of 1542. Philip II of Spain married Mary I of England, making Philip king of Spain and of England and Ireland. Mary's early death without issue prevented a closer personal union of the countries.

Elizabeth acquired the crown following Mary's death in 1558. In 1569, an Elizabethan army of 12,000 put down the Northern Rebellion, executing 450 of the Catholic rebels, many of whom were half-hanged and then disemboweled. The cold war that followed between England and Spain intensified as Elizabeth supplied aid to Protestant Dutch rebels fighting King Philip II of Spain and sanctioned corsair raids on Spanish commerce and colonies in the West Indies.[1]

Gold and diplomacy

The "Treasure crisis" of 1568 was Elizabeth's seizure of gold from Spanish ships in English ports in November 1568. Chased by privateers in the English channel, five small Spanish ships carrying gold and silver worth 400,000 florins (£85,000) sought shelter in English harbors at Plymouth and Southampton. The English government headed by William Cecil gave permission. The money was bound for the Netherlands as payment for Spanish soldiers who were fighting rebels there. Queen Elizabeth discovered that the gold was not owned by Spain, but was still owned by Italian bankers. She decided to seize it, and treated as a loan from the Italian bankers to England. The bankers agree to her terms, so Elizabeth had the money and she eventually repaid the bankers. Spain reacted furiously, and seized English property in the Netherlands and Spain. England reacted by seizing Spanish ships and properties in England. Spain reacted by imposing an embargo preventing all English imports into the Netherlands. The bitter diplomatic standoff lasted for four years.[2] However neither side wanted war. In 1573, the Convention of Nymegen was a treaty where England promised to end support for raids on Spanish shipping by English privateers such as Francis Drake and John Hawkins. It was finalized in the Convention of Bristol in August, 1574 in which both sides paid for what they had seized. Trade resumed between England and Spain and relations improved.[3]

War and Armada

| Spanish Armada | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

154 ships[1] 2,431 guns (including 1,307 small caliber cannon mounted in the ships' castles as anti-personnel weapons)[1] 19,000 soldiers

|

197 ships[1] 1,972 guns (including 497 long-range culverins or demi-culverins)[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

18,000 dead (1,500 KIA)[1] 63 ships lost[1] Scotland and Ireland: 1,000 killed by locals[1] | Minimal | ||||||

| The Spanish ships were filled with rods of iron, thumbscrews, and other instruments of torture to be used once the Spanish Inquisition was set up in England.[4] | |||||||

In 1585, as relations between England and Spain worsened, Queen Elizabeth once again authorized Francis Drake to disrupt Spanish shipping. He sacked Santo Domingo and Cartagena, which became the opening salvo of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604). After almost two years of preparation, the Spanish Armada was ready to sail. Its 154 ships carried 19,000 soldiers (17,000 Spanish, 2,000 Portuguese) and 8,000 sailors, as well as 180 clerics who were to help reestablish Catholicism in England. The plan was for the Spanish Armada to sail up the English Channel in a crescent formation to clear a path for the entry of army troops stationed in the Netherlands. The first attempt to sail in May 1588 ended when the Spanish Armada ran into storms and the fleet lost five ships.

Storms forced the fleet to stay put at A Coruña until July. Finally, they reached Lizard Point on July 29. The English fleet was at Plymouth and followed the Armada up the Channel. The first encounter was off Plymouth, July 21, the second off Portland Bill, July 23, the third off the Isle of Wight, July 24. The Armada was not seriously damaged and its formation remained intact. On July 27, the Armada had reached the Strait of Dover and anchored off Calais. The next day, the English set several of their ships on fire and sent them out to the English Channel, hoping they would destroy the ships of the Spanish fleet. The ships of the Armada cut their cables thus losing their anchors and scattered throughout the Channel breaking the crescent formation the fleet needed to maintain until troops arrived from the Netherlands. The English attacked the vulnerable Spanish ships at this conflict, known as the Battle of Gravelines on July 29.

The Armada lacked the ammunition to continue combat with the English squadrons (the Spanish had expended 125,000 cannonballs against the English).[1] Consequently, the Spanish commander decided to return home by way of the North Sea and on around the British Isles. It was in this homeward voyage that the Spanish Armada truly died. Disease, starvation, and storm chased the Spanish all along the coasts of Scotland and Ireland through August and September. At least 19 ships wrecked on those stormy shores. As many as 1,000 men from those foundering ships struggled ashore only to be murdered by local inhabitants. Another 35 ships disappeared under circumstances unknown. All together, 63 vessels of the Spanish Armada failed to return and total deaths numbered 18,000 (1,500 KIA).[1]

The defeat of the Armada was a huge blow to Spanish power. Catholicism was never restored in England, the Spanish influence in the Netherlands gradually diminished and Drake increased his raids on Spanish colonies and treasure ships. A new front opened in the war between Spain and England, the coast of northern France. In 1590, the Spanish occupied Brittany from where they had a base to attack Cornwall. In one such raid in 1595, Mousehole, Newlyn and Penzance were sacked and burned. Only a few Medieval and Tudor buildings survived the attack. The Spanish only withdrew once a sizeable force had been mustered on land and, more significantly, Drake had sailed from Plymouth with a naval force to intercept the Spanish raiders.[5] This event marked the last time England was ever invaded by hostile forces.

Peace between England and Spain was not reached until 1603 when James I, son of Mary, Queen of Scots, succeeded the childless Elizabeth to the throne.[6] England was run into serious debt by the war. It also had its colonial plans thwarted. The Spanish were able to stop English commercial shipping plying on the Atlantic. England wanted to develop colonies in North America, and the war with Spain delayed the establishment of those colonies until the Stuart period. This delay gave Spain the opportunity to consolidate and strengthen its Spanish Empire in the New World, which went on for another 200 years.[7]

Seventeenth century

In 1634, Philip IV's government managed to agree on a treaty with the English, who guaranteed to remain neutral should there be any war against the Dutch. The agreement made it possible for the Spaniards over the next six years to use England as a route for the transport of troops and silver to Flanders.[8]

Inspired by a 'Western Design' to dominate the Caribbean and 'to strive with the Spaniard for the mastery of all those seas', the lord protector of England, Oliver Cromwell, at the end of 1654 dispatched a fleet to the West Indies with the aim of seizing Hispaniola. Landing in April 1655 at Santo Domingo, they trudged through dense woodland in scorching heat. The local Spanish commander of Santo Domingo's forces, the Count of Peñalva, had positioned his musketeers and lancers—a motley crowd of mestizos and mulattoes —at critical places along the road.[9] Cromwell's English forces were dealt a devastating defeat at Santo Domingo.[10] By the time the army re-embarked at their original landing point on 28 April, over 1,000 soldiers were dead in contrast to reported Spanish losses of 25 dead and a similar number wounded.[11] The one consolation that emerged in the midst of this failure was the successful invasion of Jamaica that transformed it into an English colony.

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) saw the invasion of Spain by the Holy Roman Empire (mainly Austria and Prussia, as well as other minor German states), Great Britain, the Dutch Republic, the Duchy of Savoy and the Kingdom of Portugal in an attempt to force the Habsburg candidate onto the Spanish throne against the wishes of the Spanish people (with the exception of the Catalans), loyal to the Bourbon prince the Duc of Anjou, who was eventually enthroned. In this war, Spain lost Menorca and Gibraltar to the British but the Bourbon dynasty remains on the Spanish throne to this day.

Eighteenth-century imperial warfare

The Treaty of Utrecht that ended the War of Spanish succession was followed within two years by the death of the French King Louis XIV. This fundamentally changed the European system. Louis XV was in his minority when he ascended to the French throne, and in response, Philip V attempted to make Spain the dominant continental power. This began with the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720), in which Great Britain and France were allies against Spain when Spain attempted to reclaim territories in Italy. In 1719, the Spanish attempted to carry the conflict to the British Isles. An expedition of 29 ships carrying 6,000 soldiers sailed for Scotland, but most of it was scattered in storms and only 327 Spanish regulars managed to land in Scotland, where they were joined by 1,000 Scottish Jacobites.[1] The British routed the invaders at Glen Shiel on June 10.

Where continental Europe had been the focus of the conflict between Great Britain and France during the War of Spanish Succession, conflicts between Great Britain and Spain were largely focused in the Caribbean, and in North America.

The British had been relatively late to settle on the continent, but had built up a number of successful colonies with rapidly expanding populations. They began to challenge the Spanish monopoly on trade in South America, which the Spanish tried to prevent by passing laws against non-Spanish traders. These longstanding policies had proved a source of conflict in the mid 17th century, and again became a source of conflict after the Treaty of Utrecht included an Asiento which allowed the South Sea Company to trade with Spain's South American colonies. In the Anglo-Spanish War (1727–1729), the Royal Navy launched unsuccessful operations against Blockade of Porto Bello. These economic conflicts did not cease, and one such illegal trader, Captain Robert Jenkins, had his ear cut off as a punishment in 1739, which later caused outrage in Britain and led to the War of Jenkins' Ear, an element of the wider War of the Austrian Succession.

The British started the war by capturing and sacking Porto Bello, a major Spanish trading and naval base. The British triumph was hailed throughout its empire, and a number of streets are still named Portobello. However, a subsequent large-scale attack on Cartagena de Indias ended with a British withdrawal. All the while, Spanish vessels menaced commercial shipping at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, seizing several ships as they entered or cleared the river. These Spanish vessels were largely manned by negroes and mulattoes.[12] For eight years, these privateers infested North Carolina's waters, captured merchant vessels, ravaged the coast, plundered towns, and levied tribute on the inhabitants almost at will.[13] In the summer of 1742, the Spanish invasion of Georgia created such fear throughout the colony that many people refugeed to South Carolina or elsewhere.[14] The military activity on St. Simons Island culminated with the Battle of Bloody Marsh and the withdrawal of the Spanish.

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War lasted between 1756–1763, arraying Prussia, Great Britain and Hanover (with the British king as its prince-elector) against Austria, France, Russia, Sweden, and most smaller German states. Spain was drawn into the conflict later in 1761, on the side of France. British colonies in the Americas were on this war, but had to pay long, heavy taxes. In that period, Spain lost control of Florida to Great Britain but recovered the territory years later during the Treaty of Paris 1789, receiving New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi River from the French instead.

American Revolutionary War

| Anglo-Spanish War (1779–83) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Bernardo de Gálvez, Matías de Gálvez, Luis de Córdova y Córdova, Juan de Lángara |

George Brydges Rodney, Richard Howe, George Augustus Eliott, John Campbell | ||||||||

Hoping to gain revenge on the British for their defeat during the Seven Years' War, France offered support to rebel American colonists seeking independence from Britain during the American Revolutionary War and in 1778 entered the war on their side. They then urged Spain to do the same, hoping the combined force would be strong enough to overcome the British Royal Navy and be able to invade England. In 1779 Spain joined the war, hoping to take advantage of a substantially weakened Britain.

Bernardo de Gálvez, governor of Spanish Louisiana, commanded a motley force composed of Puerto Ricans, Venezuelans, Dominicans, Salvadorians, Nicaraguans and Mexicans during the revolutionary war.[15] They distracted the British from the revolution by capturing the cities of Mobile, Pensacola and St. Louis.[15]

In Europe, Britain's traditional allies Austria and Portugal remained neutral, leaving them isolated. Because of this there was virtually no military activity in continental Europe aside from the Great Siege of Gibraltar. Despite a prolonged besiegement, the British garrison there was able to hold out until relieved and The Rock remained in British hands following the Treaty of Paris. The siege lasted three years and seven months and was the longest in British military history. During those years the rock had been hit by 244,104 artillery rounds from guns ashore and 14,283 from cannon afloat.[1] The 663 guns of the defenders had in reply fired 200,600 rounds and British ships had hurled another 5,000 shells. The defenders lost 333 KIA, 1,010 WIA, and 1,034 dead of disease. The men serving the garrison's guns had lost 196 killed or wounded. In addition, 196 civilian employees were killed and 800 died of disease. The besiegers had lost in excess of 6,000 killed or wounded.[1]

Unlike their French allies (for whom the war proved largely to be a disaster, financially and militarily) the Spanish made a number of territorial gains, recovering Florida and Menorca. Despite this there were ominous signs for the Spanish, as the combined French and Spanish fleets had been unable to gain mastery of the seas and had also failed in two of their key objectives, regaining Gibraltar and an invasion of Great Britain.

Nootka crisis with Britain, 1789–1795

The Nootka Crisis was a crisis with Britain starting in 1789 at Nootka Sound, an unsettled area at the time that is now part of British Columbia, Canada. Spain seized small British commercial ships engaged in the fur trade in an area on the Pacific on an area on the Pacific Coast. Spain claimed ownership based on a papal decree of 1493 that Spain said gave it control of the entire Pacific Ocean. Britain rejected the Spanish claims and used its greatly superior naval power to threaten a war and win the dispute.[16] Spain, a rapidly fading military power, was unable to depend upon its longtime ally France, which was torn by internal revolution. The dispute was settled by negotiations in 1792–94, which became friendly when Spain switched sides in 1792 and became an ally of Britain against France. Spain surrendered to Britain many of its trade and territorial claims in the Pacific, ending a two-hundred-year monopoly on Asian-Pacific trade. The outcome was a victory for mercantile interests of Britain[17] and opened the way to British expansion in the Pacific.[18][19]

French Revolution

The aftermath of the 1789 French Revolution unusually saw Britain and Spain as allies for the first time in well over a century. After King Louis XVI of France was executed in 1793 Britain joined Spain in a growing coalition of European states trying to invade France and defeat the revolution. The coalition suffered a number of defeats at the hands of the French and soon broke up. Spain, influenced by the pro-French Manuel de Godoy, made peace in 1795 while Britain continued to fight on.

In 1796 Spain signed the Treaty of San Ildefonso and aligned with the French against the British.

Napoleonic Wars

At the start of the Napoleonic Wars, Spain again found itself allied with France, and again found itself outgunned at sea, notably at the Battle of Trafalgar. British attempts to capture parts of the Spanish colonial empire were unsuccessful and included failures at Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Puerto Rico, and the Canary Islands. When Napoleon invaded Iberia to force Portugal to accept the Continental System, and to place his brother on the Spanish throne, the British and (most) Spanish ended up on the same side, united against French invasion. A united British-Spanish-Portuguese army, under the command of the Duke of Wellington, eventually forced the French out of Spain, in the Peninsular War, which the Spanish call their War of Independence.

Atlantic slave trade

In the 19th century, the British Empire was at the height of its power, and the United Kingdom sought to end the Atlantic slave trade, the process by which the slave population in the Americas and specially in the United States were replenished and enlarged, which the United Kingdom had outlawed in 1807.

At the 1817 London Conference, the British pressured the major European colonial powers, including Spain, to agree to abolish the slave trade. Under the agreement, Spain agreed to end the slave trade north of the Equator immediately, and south of the Equator by 1820. British naval vessels were given the right to search suspected slavers. Despite overwhelming British naval supremacy, the trade continued. In 1835, the Anglo-Spanish agreement on the slave trade was renewed, and the rights of British captains to board and search Spanish ships were expanded. Mixed British-Spanish commissions were established at Freetown and Havana. Vessels carrying specified 'equipment articles' (including extra mess gear, lumber, foodstuffs) were declared prima facie to be slavers. However, after the First Carlist War, the leverage afforded by British political support for the Spanish government declined, and the British abolitionist movement focused on the United States and Brazil. Slavery was abolished in Spain's main Caribbean colony, Cuba, in 1888, over fifty years after the practice was outlawed across the British Empire.

Carlist Wars

During the Carlist Wars, Spain was wracked by civil war, as a result of a power struggle between the royal heir, Isabella and Carlists, led by the Pretender, Don Carlos, her uncle. Fearing a resurgent theocratic Spain, the possible re-emergence of long-silent pretenders to the British throne, a new Spanish monarch that might refuse to accept the independence of Spain's lost Latin American colonies, and domestic secessionism (particularly amongst Irish Catholics), the United Kingdom steadfastly supported Isabella who was a liberal instead of the Carlist pretenders who were reactionaries.

In 1835, the United Kingdom instigated the foundation of the Quadruple Alliance, between the UK, Spain, France, and Portugal, which supported Queen Isabella's reign. During the First Carlist War, the United Kingdom subsidised the Spanish armed forces, just as it had done during the Peninsular War. This was vital to the Spanish war economy, as, since the Napoleonic Wars, the Spanish armed forces had been poorly funded, a legacy of the loss of the majority of Spain's colonial empire. Furthermore, the UK provided a large direct military contribution; the 10,000-strong British Legion, led by George de Lacy Evans, saw action in Navarre and contributed greatly to the suppression of the revolt.

Twentieth century

Spain remained neutral in the First World War. During the Spanish Civil War, the government of the United Kingdom decided to stay neutral, supporting neither the Republican government nor Franco's Nationalists, although a few thousand British volunteers fought on the Republican side. Franco had substantial support from the fascist regimes of Germany and Italy and, after his victory, he was under strong pressure to join them during the Second World War. However, he chose to remain out of the war, although Spain's official status was that of "non-belligerent" instead of "neutral", expressing its alignment with the Axis Powers. Following the end of the war, frosty relations continued between the two states until the end of the Franco era and the democratisation of Spain, with this relations warmed rapidly, as trade and tourism became significant between the two countries.

Royal marriages

- Eleanor of England and Alfonso VIII of Castile

- Richard I of England and Berengaria of Navarre

- Edward I of England and Eleanor of Castile

- John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, and Constance of Castile

- Katherine of Lancaster and Henry III of Castile

- Henry IV of England and Joanna of Navarre

- Arthur, Prince of Wales, and Catherine of Aragon

- Henry VIII of England and Catherine of Aragon

- Mary I of England and Philip II of Spain

- Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg and Alfonso XIII of Spain

Armed conflict

Wars between the British and the Spanish include:

- War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1713)

- Queen Anne's War (1702–1713)

- Battle of Flint River (1702)

- Siege of St. Augustine (1702)

- Apalachee massacre (1704)

- Lefebvre's Charles Town expedition (1706)

- Siege of Pensacola (1707)

- Queen Anne's War (1702–1713)

- War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720)

- Anglo-Spanish War of 1727–1729

- War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–1742), which later merged into the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748)

- Siege of St. Augustine (1740)

- Spanish raids on the coast of North Carolina (1741–48)

- Invasion of Georgia (1742)

- Anglo-Spanish War of 1761–1763 was part of the Seven Years' War

- Anglo-Spanish War of 1779–1783 was part of the American Revolutionary War

- Capture of Fort Bute (1779)

- Battle of Baton Rouge (1779)

- Battle of Fort Charlotte (1780)

- Battle of St. Louis (1780)

- Battle of Mobile (1781)

- Siege of Pensacola (1781)

- Battle of Arkansas Post (1783)

- Anglo-Spanish War of 1796–1807 was part of the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars

Present day

In the present day, Spain and the United Kingdom maintain very good relations, both being members of NATO, OECD, and for the moment the European Union. They have many common laws due to EU membership. However, there are a few problems that strain relations slightly, and the withdrawal negotiations may increase strains over some issues.

Gibraltar

The status of Gibraltar is a major point of contention in relations between the two nations, dating back to the conflicts in the early 18th century. The official status of Gibraltar is that of a British overseas territory. Captured by Dutch and British troops in 1704, the Spanish king transferred the territory to Great Britain in 1713 under the terms of Article X of the Treaty of Utrecht.

In two referendums, held in September 1967 and November 2002, the people of Gibraltar rejected any proposal for the transfer of sovereignty to Spain. The 2002 referendum was on a proposal for joint sovereignty which at one stage was supported by the UK Government.

Considering the Gibraltarians decolonisation subjects, Spain asserts it is a bilateral issue between sovereign nations on the grounds of the "territorial integrity" clause UN Resolutions, which according to Spain prevails over the right to self-determination to the colonists themselves.[20] On the other hand, Gibraltar's authorities consider Gibraltarian people the legitimate inhabitants of the territory, and therefore entitled to the self-determination right in compliance of the same United Nations' resolutions. Gibraltar's 2006 Constitution Order endorsed and approved by Her Majesty's Government states:

- Her Majesty’s Government will never enter into arrangements under which the people of Gibraltar would pass under the sovereignty of another state against their freely and democratically expressed wishes.[21]

In 2008, the UN 4th Committee rejected the claim that a dispute over sovereignty affected self-determination, which was a basic human right.[22]

From May 2000 to May 2001 HMS Tireless moored in Gibraltar, for repairs on the cooling system of its nuclear reactor. The presence of the nuclear vessel in Gibraltar caused outrage among environmentalists and strained relations between Spain and the UK.[23][24][25]

In February 2002, the UK formally apologised when a unit of British Royal Marines accidentally invaded La Linea de la Concepción's beach instead of Gibraltar's where the planned military training was to be conducted.[26][27]

In 2004, Spain and the United Kingdom established the Tripartite Forum for Dialogue on Gibraltar, with equal representation of both countries and the British Overseas Territory.

Waters around Gibraltar, declared by the United Kingdom as territorial waters according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (to a three-mile limit),[28] and claimed by Spain,[29][30] are other source of clash, with the Government of Gibraltar actively backing the British position naming the disputed waters as "British Gibraltar territorial waters".[31] In December 2008, the European Commission approved a Spanish request designating most of the waters around Gibraltar as one of Spain's protected nature sites under EU law. This decision is being currently challenged in the European Court of Justice by the Government of Gibraltar, backed by the British government. The Commission will defend its position and, in doing so, will be backed by Spain[32] In May 2009 Gibraltar authorities complained about the presence of a Guardia Civil Maritime Service vessel into the three-mile waters around Gibraltar, escalating to the intervention of Royal Navy Gibraltar Squadron and a diplomatic protest by the Government of the United Kingdom.[33][34][35] Further incidents occurred in November 2009.[36][37]

In July 2009 Miguel Ángel Moratinos, the Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs visited Gibraltar to meet the British Foreign Secretary, David Miliband, and Gibraltar's chief minister, Peter Caruana, becoming the first Spanish official to visit the territory since Spain closed its consulate in Gibraltar in the 1950s. The sovereignty issue was not dealt with, given its controversial nature, and the three-way talks focused on other subjects such as cooperation on the environment, maritime matters, and ways of further facilitating the Moroccan community in Gibraltar to transit Spain en route to and from Gibraltar and Morocco.[38][39]

In December 2009, a Guardia Civil launch entered the Gibraltar harbour. Three armed officers landed in Gibraltar illegally and, along with a fourth, were arrested by the Royal Gibraltar Police.[40] Many such incidents occur, with a more recent event being the arresting of Gibraltarian fisherman inside the waters of Gibraltar, confiscation of equipment and transfer of the individuals to Spain. This was strongly condemned by the UK Government,[41] and the UK's method of quiet diplomacy with Spain was criticised by a local newspaper, which called for more 'open' diplomacy.[42]

Between January and November 2012, around 200 incursions by Spanish vessels into Gibraltar waters were recorded, as opposed to 23 in 2011 and 67 in 2010. In December 2012, one day after an incursion by a Spanish warship, a Royal Navy Type 23 frigate, HMS Sutherland arrived on a scheduled visit. Rather than taking on stores and fuel and proceeding as had been planned, the frigate and its Merlin helicopter conducted a patrol of Gibraltar waters as a message.[43]

In February 2013, a Spanish Navy patrol ship, the Tornado, a 94-meter long armed patrol vessel, larger than both of the Royal Navy light craft stationed in Gibraltar at the time, entered Gibraltar's waters and cruised in them irregularly for about 20 minutes, during which the Royal Navy sent it repeated radio warnings demanding it leave, before leaving. The British Foreign Office protested to the Spanish government over the incident, described as the most serious Spanish incursion since the 1960s. The incident followed previous incursions involving Spanish police motorboats entering Gibraltar's waters, interfering with pleasure craft and protecting fishermen using illegal practices.[44]

The intensity of the disagreement about Gibraltar has been perceived in different ways by the two countries. According to former Spanish prime minister Felipe González, "For the British, Gibraltar is a visit to the dentist once a year when we meet to talk about it. For us, it is a stone in the shoe all day long".[45]

Fishing dispute

The United Kingdom and Spain have had several recent disputes over fishing rights, particularly with regards to the European Union's Common Fisheries Policy. When Spain became a member state in 1986, it had the world's sixth largest fishing fleet,[46] and much of the economies of Galicia, Asturias, and Cantabria depended upon catches by Spanish boats outside Spain's national Exclusive Economic Zone, just as they do today.

To prevent the fleets of other EU members (particularly Spain) taking up the UK's Common Fisheries Policy quota, the UK sought to create a framework that discriminated between British- and Spanish-owned boats, regardless of flag flown, so that its waters wouldn't be over-fished by foreign-owned trawlers. Due to fishing's importance to some of the regional economies of Spain, the Spanish government protested vehemently, but had no power to prevent the UK determining its own domestic policies. However, when the Single European Act was implemented, in 1987, this became illegal under EU law, and a Spanish company successfully challenged the right of the British government to prevent Spanish fishermen taking up the British quota in what has now become known as the Factortame case. In total, £55m has been paid out by the British government to Spanish parties (both public and private) for loss of earnings.[47]

To this day, the large Spanish fishing fleet does the majority of its fishing outside Spain's EEZ, as far away as Canada and Namibia.[48] Nonetheless, a large part of its business comes from fishing in the waters of northern Europe, particularly those of the United Kingdom and Ireland. At times of debate of the United Kingdom's declining fish stocks, this has caused strained relations between Spain and the UK, and particularly between Spain and the membership of the devolved Scottish institutions, since Scotland is more dependent upon fishing than the rest of the UK.

Scotland and Catalonia

Scotland held a referendum on independence from the UK on 18 September 2014. In November 2013 the Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy had stated that an independent Scotland would have to reapply for membership of the European Union, causing considerable irritation to the Scottish Government.[49] Relations between the Spanish and Scottish governments deteriorated further when the Scottish Government alleged that a senior UK Treasury official visited Spain ostensibly to co-ordinate British and Spanish opposition to the independence movements in Scotland and Catalonia.[50] Rajoy was one of the few European heads of government to explicitly voice opposition to Scottish independence, primarily due to his fears that it would encourage the separatist drive in Catalonia.[51] On the issue of Catalan independence, Prime Minister David Cameron had said that "I don't believe that, in the end, [it's right to] try to ignore these questions of nationality, independence, identity"... I think it’s right to make your arguments, take them on and then you let the people decide" though he also added that "I would never presume to tell people in Spain how to meet these challenges themselves; it's a matter for the Spanish Government and the Spanish Prime Minister."[52]

Migration

The 2001 UK Census recorded 54,482 Spanish-born people living in the UK.[53] In comparison, it is estimated that 990,000 British-born people live in Spain.[54][55] Of these, according to the BBC and contrary to popular belief, only about 21.5% are over the age of 65.[56]

In 2011, Spanish migration to the UK went up 85%.[57] As for 2012, it was recorded that 69,097 Spanish-born people live in the United Kingdom.[58] On the other hand, in the same period 397,535 British-born people were living in Spain [59]

Twinnings

The list below is of British and Spanish town twinnings.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- ↑ Wallace T. MacCaffrey, The Shaping of the Elizabethan Regime (1968) pp 271-90.

- ↑ John Wagner, ed. Historical Dictionary of the Elizabethan World: Britain, Ireland, Europe and America (1999) pp 39, 216, 307-8.

- ↑ The Penny Protestant operative.

- ↑ Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly: the complete guide. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 20.

- ↑ Colin Martin and Geoffrey Parker, The Spanish Armada (2nd ed., 1999.

- ↑ Castleden, Rodney. Conflicts that Changed the World. Canary Press eBooks.

- ↑ Kamen, Henry. Spain, 1469-1714: A Society of Conflict.

- ↑ America and the Americas: The United States in the Western Hemisphere.

- ↑ Between Two Worlds: How the English Became Americans.

- ↑ Bradley, Peter T. British Maritime Enterprise in the New World: From the Late Fifteenth to the Mid-eighteenth Century. p. 152.

- ↑ "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina".

- ↑ Powell, William S. (2010). North Carolina Through Four Centuries. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 99.

- ↑ Georgia Journeys: Being an Account of the Lives of Georgia's Original Settlers and Many Other Early Settlers. University of Georgia Press. 2010. p. 17.

- 1 2 Archuleta, Roy A. Where We Come from. p. 69.

- ↑ John Holland Rose, William Pitt and national revival (1911) pp 562–87.

- ↑ Nootka Sound Controversy, The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ↑ Pethick, Derek (1980). The Nootka Connection: Europe and the Northwest Coast 1790–1795. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. p. 18. ISBN 0-88894-279-6.

- ↑ Emilia Soler Pascual, "Floridablanca and the Nootka Crisis." International journal of Canadian studies= Revue internationale d'études canadiennes 19 (1999): 167–180. a Spanish perspective, translated into English.

- ↑ Surya Prakash Sharma (1997). Territorial acquisition, disputes, and international law. The Hague. p. 311. ISBN 90-411-0362-7. : "[Spain] has insisted that allowing the Gibraltarians to retain ties with Britain would constitute a partial disruption of Spain's territorial integrity in violation of paragraph 6 of 1514(XV)"

- ↑ http://www.gibraltarlaws.gov.gi/constitution/Gibraltar_Constitution_Order_2006.pdf

- ↑ "FOLLOWING INTENSE DEBATE, FOURTH COMMITTEE APPROVES AMENDED OMNIBUS TEXT ON NON-SELF-GOVERNING TERRITORIES - Meetings Coverage and Press Releases".

- ↑ "Nuclear sub leaves Gibraltar". BBC News. 7 May 2001. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (27 October 2000). "Spain protests overleaking nuclear sub". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "Ten Greenpeace volunteers arrested in demonstration against HMS Tireless in Gibraltar - Greenpeace UK".

- ↑ Sengupta, Kim (19 February 2002). "A beach too far: British marines invade Spain by mistake". The Independent. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ Tremlett, Giles (19 February 2002). "Tell it to the marines... we've invaded the wrong country". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ http://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/ibru/publications/full/bsb7-1_oreilly.pdf

- ↑ "Declarations or Statements upon UNCLOS ratification".

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Spain (2008). Informe sobre Gibraltar (PDF) (in Spanish). pp. 8–9.

- ↑ "Action brought on 6 May 2009 — Government of Gibraltar v Commission (Case T-176/09)".

- ↑ "Spain/UK to cross swords in Gibraltar waters legal challenge before EC".

- ↑ "Britain tells Spain violation unacceptable". Archived from the original on 2009-06-01.

- ↑ Milland, Gabriel (23 May 2009). "Return of the Armada as Spain 'invades' Gibraltar".

- ↑ "Who Owns Gibraltar? Spain Takes a Step Onto the Rock". Time. 21 July 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "Tension heightens in Gibraltar waters".

- ↑ Govan, Fiona (20 November 2009). "Royal Navy used 'Spanish flag' for target practice off Gibraltar". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "Trilateral Communique" (PDF).

- ↑ Keeley, Graham (21 July 2009). "Miguel ngel Moratinos Spanish Foreign Minister met by protests on visit to Gibraltar". The Times. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "Incident at Harbour Views".

- ↑ http://www.panorama.gi/localnews/headlines.php?action=view_article&article=9094&offset=0

- ↑ http://www.panorama.gi/localnews/headlines.php?action=view_article&article=9096&offset=0

- ↑ "Royal Navy shows the flag in Gibraltar waters; 197 Spanish unlawful incursions this year".

- ↑ Howarth, Mark (6 February 2013). "Tensions growing off Gibraltar after Royal Navy confronts Spanish warship that had strayed into British waters". Daily Mail. London.

- ↑ Peter Gold (2005). Gibraltar: British or Spanish?. Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 0-415-34795-5.

- ↑ "UK and Spain Fishing Dispute". American University, 11 January 1997. Accessed 22 June 2006.

- ↑ House of Commons Written Answers for 8 February 2001. Parliament of the United Kingdom, 8 February 2001. Accessed 22 June 2006.

- ↑ "Iyambo in fish talks with Spanish fisheries minister". Namibia Economist, 17 March 2006. Accessed 22 June 2006.

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-25132026 BBC

- ↑ "Salmond: Spain is working with UK to thwart Yes vote".

- ↑ "Scottish or Catalan vote 'torpedoes EU', says Spain's Rajoy". BBC. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ CNA. "Catalan News Agency - David Cameron: "let the people decide" and do not "ignore questions of nationality, independence, identity"".

- ↑ "Country-of-birth database". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - Special Reports - Brits Abroad".

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - UK - Brits Abroad FAQs: The data".

- ↑ BBC News. 6 December 2006 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/in_depth/brits_abroad/html/europe.stm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Spanish Immigration to the UK up 85%: What This Means for Payments Abroad – LONDON, September 14, 2011 /PRNewswire/". United Kingdom: Prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ↑ http://www.ine.es/prensa/np705.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ine.es/prensa/np710.pdf

Further reading

- Dadson, Trevor J. Britain, Spain and the Treaty of Utrecht 1713–2013 (2014).

- del Campo, Luis Martínez. Cultural Diplomacy: A Hundred Years of the British-Spanish Society (2016).

- Edwards, Jill. The British Government and the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939 (2014).

- Finucane, Adrian. The Temptations of Trade: Britain, Spain, and the Struggle for Empire (2016).

- Gold, Peter. Gibraltar: British or Spanish? (2005).

- Hayes, Paul. Modern British Foreign Policy: The Nineteenth Century 1814-80 (1975) pp. 133–54.

- Hopkins, James. Into the Heart of the Fire: The British in the Spanish Civil War (2000).

- Horn, David Bayne. Great Britain and Europe in the eighteenth century (1967), covers 1603 to 1702; pp 269–309.

- Rabb, James W. Spain, Britain and the American Revolution in Florida 1763–1783 (2007)

- Richards, D.S. Peninsula Years: Britain's Red Coats in Spain and Portugal (2002)

.svg.png)