Carmarthen

Carmarthen

| |

|---|---|

| |

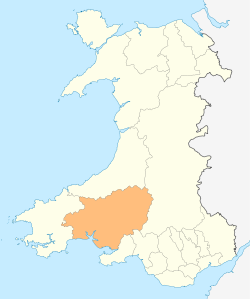

Carmarthen Carmarthen shown within Carmarthenshire | |

| Population | 14,185 [1] (2011 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SN415205 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CARMARTHEN |

| Postcode district | SA31-33 |

| Dialling code | 01267 |

| Police | Dyfed-Powys |

| Fire | Mid and West Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| EU Parliament | Wales |

| UK Parliament | |

| Welsh Assembly | |

Carmarthen (/kɑːrˈmɑːrðən/; Welsh: Caerfyrddin [kɑːɨrˈvərðɪn], "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire in Wales and a community. It lies on the River Towy 8 miles (13 km) north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay.[2][3] Carmarthen has a strong claim to be the oldest town in Wales – the settlements of Old Carmarthen and New Carmarthen became one borough in 1546.[4] Carmarthen was the most populous borough in Wales in the 16th–18th centuries, described by William Camden as "the chief citie of the country". Growth stagnated by the mid-19th century, as new economic centres developed in the South Wales coalfield.[4] The population in 2011 was 14,185, down from 15,854 in 2001.[5] Dyfed–Powys Police headquarters, Glangwili General Hospital and a campus of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David are located in Carmarthen.

History

Early history

When Britannia was a Roman province, Carmarthen was the civitas capital of the Demetae tribe, known as Moridunum[2] ("Sea Fort"). It is possibly the oldest town in Wales, recorded by Ptolemy and in the Antonine Itinerary. The Roman fort is believed to date from about AD 75. A Roman coin hoard was found nearby in 2006.[6] Near the fort is one of seven surviving Roman amphitheatres in Britain and only two in Roman Wales (the other being at Isca Augusta, Roman Caerleon). It was excavated in 1968. The arena itself is 50 by 30 yards (about 46 by 27 metres); the cavea (seating area) is 100 by 73 yards (92 by 67 metres). Veprauskas has argued for its identification as the Cair Guorthigirn[7] ("Fort Vortigern") listed by Nennius among the 28 cities of Britain in his History of the Britains.[8] Evidence of the early Roman town has been investigated for a number of years, uncovering urban sites likely to date from the second century.[9]

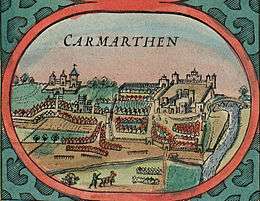

During the Middle Ages, the settlement was known as Llanteulyddog ('St Teulyddog's)[10] and accounted one of the seven principal sees in Dyfed.[11] The strategic importance of Carmarthen was such that the Norman William fitz Baldwin built a castle there, probably about 1094. The current castle site is known to have been used since 1105. The castle itself was destroyed by Llywelyn the Great in 1215 but rebuilt in 1223, when permission was granted to build a town wall and crenellate the town, making it one of the first medieval walled towns in Wales. In 1405, the town was captured and the castle was sacked by Owain Glyndŵr. The Black Book of Carmarthen, written about 1250, is associated with the town's Priory of SS John the Evangelist and Teulyddog.

The Black Death of 1347–49 arrived in Carmarthen through the thriving river trade.[12] It destroyed and devastated villages such as Llanllwch. Local historians site the plague pit for the mass burial of the dead in the graveyard that adjoins the Maes-yr-Ysgol and Llys Model housing at the rear of St Catherine Street.

Priory

The ancient Clas church of Llandeulyddog was an independent, pre-Norman religious community which became in 1110 the Benedictine Priory of St Peter,[13] only to be replaced 15 years later by the Augustianian Priory of St John the Evangelist and St Teulyddog.[14][15] This stood near the river, at what is now Priory Street (51°51′36″N 4°17′51″W / 51.8601°N 4.2975°W, SN418204). The site is now a scheduled monument.

Grey Friars

During the 13th century, Franciscan Friars (Grey Friars, or Friars minor) became established in the town, and by 1284 had their own Friary buildings on Lammas Street (51°51′21″N 4°18′33″W / 51.855794°N 4.309076°W), on a site now occupied by a shopping centre.[16] The Franciscan emphasis on poverty and simplicity meant the Church was smaller (reportedly "70 to 80 feet long and 30 feet broad" – 21/24 by 9 m) and more austere than the older foundations, but this did not prevent the accumulation of treasures, and it became a much sought after location for burial.[17] In 1456 Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond died of plague in Carmarthen,[18] three months before the birth of his son, the future King Henry VII. Edmund was buried in a prominent tomb in the centre of the choir of the Grey Friars Church.[17] Other notable burials were of Rhys ap Thomas and Tudur Aled.[16]

The Friary was dissolved in 1538, and many unsuccessful plans were made for the building. Even before the friars had left, in 1536, William Barlow campaigned to have the cathedral moved into it, from St David's,[17] where the tomb and remains of Edmund Tudor were moved after the Carmarthen buildings were deconsecrated. There were repeated abortive attempts to turn the buildings into a grammar school.[17] Gradually they became ruined, although the church walls were still recognisable in the mid-18th century.[17] By 1900 all the stonework had been stripped away and there were no traces above ground. The site remained undeveloped until the 1980s and 1990s, after extensive archaeological excavations of first the monastic buildings and then the nave and chancel of the church. These confirmed that the former presence of a church, a chapter house and a large cloister, with a smaller cloister and infirmary added subsequently. Over 200 graves were found in the churchyard and 60 around the friars' choir.[19]

Arthurian legend

.jpg)

According to some variants of the Arthurian legend, Merlin was born in a cave outside Carmarthen. The town's Welsh name, Caerfyrddin, is widely claimed to mean "Merlin's fort", but it is also suggested the reality may be the other way around, that the name Merlin may have originated from the town's name and be an anglicised form of Myrddin.[20] (See Merlin § Name and etymology). An alternative explanation is that Myrddin is a corruption of the town's Roman name. Furthermore, many areas surrounding Carmarthen still allude to this, such as nearby Bryn Myrddin (Merlin's Hill).

Legend also had it that if a particular tree called Merlin's Oak fell, it would be the downfall of the town. Translated from Welsh, it reads: "When Merlin's Oak comes tumbling down, down shall fall Carmarthen Town."[21] To obstruct this, the tree was dug up when it died and pieces of it remain in the town museum.

The Black Book of Carmarthen includes poems with references to Myrddin (Ymddiddan Myrddin a Thaliesin, "Conversation of Merlin and Taliesin") and possibly to Arthur (Pa ŵr yw'r Porthor?, "What man is the porter?"). The interpretation of these is difficult, as the Arthurian legends were known by this time and detail of the modern form had been described by Geoffrey of Monmouth before the book was written.

Early modern

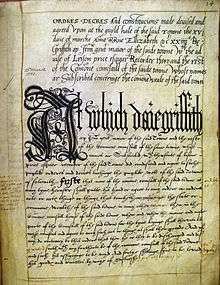

The 'Book of Ordinances', 1569–1606, is one of the earliest surviving minute books of a town in Wales. It gives a unique picture of an Elizabethan Welsh town.[22]

Following the Acts of Union, Carmarthen became judicial headquarters of the Court of Great Sessions for southwest Wales. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the town's dominant pursuit was still agriculture and related trades, including woollen manufacture. Carmarthen was made a county corporate by a charter of James I in 1604. This decreed that Carmarthen should be known as the 'Town of the County of Carmarthen' and have two sheriffs. This was reduced to one sheriff in 1835 and the ceremonial post continues to this day.

When the Priory and the Friary were abandoned during the dissolution of the monasteries in the reign of Henry VIII, the land being returned to the monarchy. Likewise, the chapels of St Catherine and St Barbara were lost, the church of St Peter's being the main religious establishment to survive.

During the Marian persecutions of the 1550s, Bishop Ferrar of St David's was burnt at the stake in the market square – now Nott Square. A Protestant martyr, his life and death are recorded in John Foxe's famous book of martyrs.

In 1689, John Osborne, 1st Earl of Danby, was made 1st Marquess of Carmarthen by William III. Osborne was later created Duke of Leeds in 1694, and Marquess of Carmarthen became the Duke's heir apparent's courtesy title until the Dukedom became extinct upon the death of the 12th Duke in 1964.

18th century to present

In the mid-18th century, the Morgan family founded a small-scale ironworks at the east end of the town. In 1786 lead smelting was established to process the ore carried from Lord Cawdor's mines at Nantyrmwyn, in the north-east of Carmarthenshire. Neither of these firms survived for long. The lead smelting moved to Llanelli in 1811. The ironworks evolved into tinplate works that had failed by about 1900.

In the late eighteenth century John Spurrell, an auctioneer from Bath, moved to Wales and settled in Carmarthen. He was the grandson of Robert Spurrell, a Bath schoolmaster who printed the first book, The Elements of Chronology, in the city in 1730. In 1840, a printing press was set up in Carmarthen by William Spurrell (1813–1889), who wrote a history of the town and compiled and published a Welsh-English dictionary (first published 1848) and an English–Welsh dictionary (first published 1850).[23] Today's Collins Welsh dictionary is known as the "Collins Spurrell". A local housing authority in Carmarthen is named Heol Spurrell in honour of the family.[24]

The origins of Chartism in Wales can be traced to the foundation in the autumn of 1836 of Carmarthen Working Men's Association.[25]

Carmarthen gaol, designed by John Nash, was in use from about 1789 until its demolition in 1922. The site is now occupied by County Hall, designed by Sir Percy Thomas. The gaol's "Felons' Register" of 1843–71 contains some of the earliest photographs of criminals in Britain. In 1843 the workhouse in Carmarthen was attacked by the Rebecca Rioters.

The revival of the eisteddfod as an institution took place in Carmarthen in 1819. The town hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1867, 1911 and 1974, although at least in 1974, the Maes was at Abergwili.

Carmarthen Grammar School was founded in 1587 on a site now occupied by the old hospital in Priory Street. The school moved in the 1840s to Priory Row, before relocating to Richmond Terrace. At the turn of the 20th century, a local travelling circus buried one of its elephants that fell sick and died. The grave is under what was the rugby pitch.

During World War II, prisoner-of-war camps were situated in Johnstown (where the Davies Estate now stands) and at Glangwilli — the POW huts being used as part of the hospital since its inception. To the west of the town was the "Carmarthen Stop Line", one of a network of defensive lines created in 1940–41 in case of invasion, with a series of ditches and pillboxes running north-south. Most of these structures have since been removed or filled in, but there are still two remains.[26] [27]

The Carmarthen community is bordered by those of Bronwydd, Abergwili, Llangunnor, Llandyfaelog, Llangain, Llangynog and Newchurch and Merthyr, all being in Carmarthenshire.

Carmarthen was named one of the best places to live in Wales in 2017.[28]

Governance

Carmarthen Town Council, established in 1974, consists of 18 town councillors elected from the three wards of the town. The town council's responsibilities include maintenance of the town's five parks and of the town cemetery.[29]

The three electoral wards of Carmarthen Town North, Carmarthen Town South and Carmarthen Town West each elect two county councillors to Carmarthenshire County Council.

Twin towns

Carmarthen is twinned with:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Landmarks

Carmarthen Castle

Little remains of the original medieval castle at Carmarthen, but the old Gatehouse still dominates Nott Square. The motte is also accessible to the public. Castle House, within the old walls, is a museum and Tourist Information Centre.[30]

St Peter's Church

St Peter's is the largest parish church in the Diocese of St David's and has the longest nave, being 60 metres from west porch to east window and 15 metres across the nave and south aisle.[31] It consists of a west tower, nave, chancel, south aisle and a Consistory Court. It is built of local red sandstone and grey shale. The tower contains eight bells with the heaviest, tuned to the note E, weighing 15 cwt 1 qr 18 lbs (783 kg).

Carmarthen Bridge

The concrete A484 road bridge across the River Towy was designed by the Welsh architect Clough Williams-Ellis and completed in 1937. The bridge was Grade II listed in 2003.[32] The loss of the original medieval bridge that it replaced caused controversy.

Pont King Morgan

To create better pedestrian access across the Towy from the railway station to the town centre, a cable-stayed bridge was constructed in 2005 linking to the foot of Blue Street. The cost was £2.8 million.[33] The bridge was commended in 2007 by the Structural Steel Design Awards for its high-quality detailing. Previously, access was across Carmarthen Bridge some 700 feet (210 m) to the east.[34]

Picton's monument

In 1828, a monument was erected at the west end of the town to honour Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Picton, from Haverfordwest, who had died at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. The pillar, which was about 75 ft (23 m), was designed to echo Trajan's column in Rome. A statue of Picton, wrapped in a cloak and supported by a baluster above emblems of spears surmounted the column. The structure stood on a square pedestal. Access was by a flight of steps to a small door on the east side, facing the town. A series of bas-reliefs sculpted by Edward Hodges Baily adorned the structure. Above the entrance door was the name "PICTON", and over this a relief showing the Lieutenant General falling mortally wounded from his horse on the Waterloo battlefield. "WATERLOO" was written across the top. The west side had a relief beneath the title 'BADAJOS' showing Picton scaling the walls with his men during the Battle of Badajoz in 1812. On the south side of the pedestal was a description of Picton's life in English. A Welsh version of his exploits was inscribed on the north side. Each side of the square pedestal was adorned with trophies. The top of the square column was adorned with imitative cannons on each side.

Within a few years, the monument had fallen into a dilapidated state. The sculpted bas-reliefs proved "unable to withstand Carmarthen's inclement weather", according to local antiquarians. Although Baily made replacements, they were never put up. The entire pillar was taken down in 1846. In the 1970s, the replacement sculptures were rediscovered in Johnstown. They are now on display at Carmarthenshire County Museum.

After demolition of the first monument, a new structure honouring Picton was commissioned. It was designed by architect Frances Fowler. The foundation stone was laid on Monument Hill in 1847. In 1984, the top section was declared to be unsafe and was taken down. Four years later, the whole monument was rebuilt stone-by-stone on stronger foundations.

General Nott statue and plaque to Bishop Ferrar

A statue of General Nott was erected in 1851. According to the PMSA, "The bronze statue was cast from cannon captured at the battle of Maharajpur. Queen Victoria gave 200 guineas to the memorial fund. The statue occupies the site of the market cross, which was dismantled when the market was resited and Nott Square created in 1846."[35]

The Market Square was where Bishop Robert Ferrar of St Davids was executed in March 1555. A small plaque below the statue of General Nott commemorates the place where he was burned at the stake during the Marian Persecutions.

Listed buildings

The many listed buildings in the town include The Guildhall, Capel Heol Awst, Capel Heol Dŵr, Carmarthen, Carmarthen Cemetery Chapel, Elim Independent Chapel, English Baptist Church, English Congregational Church, Penuel Baptist Chapel, Christ Church, Eglwys Dewi Sant, Church of St Mary and Eglwys Sant Ioan.

Sport

Motorcycle speedway racing was staged in the early 2000s at a track built on the showgrounds on the western outskirts of the town. The team raced in the Conference League.

The town has two rugby union teams – Carmarthen Quins and Carmarthen Athletic. The Quins currently play in the Welsh Premier Division league after their promotion to the Premiership in the 2008/2009 season.

CPC Bears is a rugby league club based in Carmarthen and the regional side for Carmarthenshire, Pembrokeshire and Ceredigion. They play in the Welsh Premier Division of the Rugby League Conference.

The town has a football team, Carmarthen Town F.C. which plays in the Welsh Premier League. It was founded in 1948 and has played at Richmond Park since 1952.

The town also has two golf courses, a leisure centre with an eight-lane, 25-metre swimming pool that is the home of Carmarthen district swimming club, a synthetic athletics track, and an outdoor velodrome. Carmarthen has an athletics team, Carmarthen Harriers. A cycle track was established in the town about 1900 and remains in use.

Transport

Carmarthen railway station is on the West Wales Line. It opened in 1852. Carmarthen town is served by rail links to Cardiff via Swansea to the east and Fishguard Harbour, Milford Haven, Tenby, Pembroke and Pembroke Dock to the west. Carmarthen town is served by daily direct intercity trains to London. It suffered a number of rail closures in the 1960s under the Beeching Axe. The one to Llandeilo closed in 1963 and one to Lampeter and Aberystwyth in 1965.

A number of major roads converge on Carmarthen, including the A40, A48, A484 and A485. The only motorway route in Carmarthenshire is the M4 between London and South Wales, as far as junction 49, the Pont Abraham services, then continuing northwest as the dual carriageway A48 to Carmarthen.

Carmarthen is a stop on the Eurolines bus route 890, which links a number of cities and towns in Munster and South Leinster in Ireland to London. The service may be used to destinations in Ireland, but may not be used to other stops in Great Britain.

There is also a Park and Ride service running daily from Monday to Saturday from 7.00 to 19.00 between Nantyci, to the west of Carmarthen town, and the town centre.[36]

Town regeneration and redevelopment

The former cattle market in the heart of the town has undergone regeneration. The new shopping centre opened on 30 April 2010.[37] The development includes a new multi-screen cinema, a Debenhams department store, a market hall, restaurants and a multi-storey car park. The new market hall opened on 8 April 2009.[38]

Notable people

- See Category:People from Carmarthen

- See Category:People from Carmarthenshire

- Joe Allen, Wales and Stoke City FC midfielder

- Dorothea Bate, archaeozoologist

- Charles Brigstcke CB, British civil servant

- Fflur Dafydd, writer and musician

- Barry Davies, Ospreys full-back

- Gareth Davies, Scarlets scrum-half

- Mark Delaney, former Wales and Aston Villa defender

- Wynne Evans, opera singer, broadcaster, presenter and actor

- Rhod Gilbert, Perrier Award Best Newcomer-nominated comedian

- Rhodri Gomer-Davies, Scarlets Centre

- Gorky's Zygotic Mynci, band formed in Carmarthen

- Geraint Griffiths, singer, songwriter and actor

- Elis James, comedian

- Stephen Jones, former Wales rugby captain

- Kate McGill, singer/songwriter

- Daniel Mulloy, screenwriter and director

- John Nash, architect, living in Carmarthen from 1784 and working on several important buildings in the area

- Daniel Newton, Scarlets fullback

- William Norton, former Wales international rugby union player

- Ken Owens, Scarlets hooker

- Rhys Priestland, Scarlets full-back, making his Wales senior team debut in 2011 Six Nations Championship against Scotland as a second-half replacement

- Iwan Rheon, actor (famous for his role in Game of Thrones) and singer/songwriter

- Byron Rogers, writer

- Matthew Stevens, snooker pro

- Nicky Stevens, member of pop group Brotherhood of Man

- Terence Thomas, Baron Thomas of Macclesfield, banker and politician

- Nik Turner, musician

- Tudur Aled, poet, buried in the Franciscan Friars' graveyard, Carmarthen, in 1525

- Philip Vaughan, ironmaster and inventor of the ball bearing

- Mary Wynne Warner, mathematician

- John Weathers, drummer

- Barry Williams, former British and Irish Lions hooker

- Scott Williams, Scarlets Centre was in the Wales senior team against the Barbarians on 4 June 2011 as a second-half replacement.

- David Glyndwr Tudor Williams, first full-time Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, 1989–1996.

Gallery

Guildhall Square, Carmarthen

Guildhall Square, Carmarthen- The new market building opened April 2009.

Apollo Cinema - the most modern purpose built cinema in Europe.[39]

Apollo Cinema - the most modern purpose built cinema in Europe.[39]- The Mount

County Hall - home of Carmarthenshire County Council

County Hall - home of Carmarthenshire County Council- Carmarthen Castle

- The Red Dragon art work on a roundabout

- St Peter's Church

- Lammas Street

Park and Ride Service

Park and Ride Service Statue of William Nott

Statue of William Nott

See also

References

- ↑ Carmarthen North, South and West wards 2011 http://ukcensusdata.com/carmarthenshirew06000010#sthash.KIAkXPeF.Zq1LWHU4.dpbs

- 1 2

- ↑ Paxton, John (1999). The Penguin Encyclopedia of Places. Penguin. p. 174. ISBN 0-14-051275-6.

- 1 2 Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- ↑ "KS01 Usual resident population: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Roman treasure discovered on farm". BBC News. 17 June 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- ↑ Veprauskas, Michael. [www.vortigernstudies.org.uk/artgue/mikecaer.htm "The Problem of Caer Guorthigirn" at Vortigern Studies]. 1998.

- ↑ "Carmarthen Roman dig is filled in after key findings". BBC News. 30 September 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ James, Heather. "The Geography of the Cult of St David" in St David of Wales: Cult, Church and Nation, p. 68. Boydell Press, 2007. Accessed 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Wade-Evans, Arthur. Welsh Medieval Law, p. 263.

- ↑ Philip Ziegler, The Black Death, Penguin, 1969, p. 199.

- ↑

- ↑ "St John's Priory". Coflein Database Record. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Site details: Carmarthen – Monastic Wales – A Comprehensive Database of Sites and Sources". Monastic Wales. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- 1 2 "Site details: Carmarthen – Monastic Wales – A Comprehensive Database of Sites and Sources". Monastic Wales. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "TheGreyFriarsOfCarmarthen < Historian < Thayersfarm". Carmarthenshirehistorian.org. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ "People: Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond – Monastic Wales – A Comprehensive Database of Sites and Sources". Monastic Wales. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ "Remnants of Carmarthen Friary – article from – Monastic Wales – A Comprehensive Database of Sites and Sources". Monastic Wales. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ Merlin’s Town, Carmarthen Town Council. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ↑ "9/11 inspires trip to 'Merlin's Oak'". walesonline.co.uk. 1 October 2003. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Carmarthenshire Archives Service: Mus.156a

- ↑ Article in Welsh Biography Online, SPURRELL family, of Carmarthen, printers: https://yba.llgc.org.uk/en/s-SPUR-CAE-1775.html?query=spurrell&field=name

- ↑ https://yba.llgc.org.uk/en/s-SPUR-CAE-1775.html

- ↑ Williams, David (1939). John Frost: A study in Chartism. Cardiff: University of Wales Press Board. pp. 100, 104, 107.

- ↑ "myADS". Archaeology Data Service. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ "myADS". Archaeology Data Service. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ "These towns have been named as the best places to live in Wales". Wales Online.

- ↑ "Carmarthen Town Council". Carmarthen Town Council. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ↑ "Discover Castle House". Discovering Carmarthenshire. Carmarthenshire County Council. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "St Peter's and its History". netministries.org. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ "Towy Bridge (that part in Carmarthen Community), Llangunnor". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ↑ "Pont King Morgan". Lunemillenniumbridge.info. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ↑ "Pont King Morgan, Carmarthen". SteelConstruction.org. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ↑ Public Monument and Sculpture Association on General Nott Statue from National Recording Project

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-10-21. Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- ↑ "Carmarthen's £74m retail centre opens". BBC News. 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ "UK | Wales | South West Wales | Revamp of the town cattle mart starts". BBC News. 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ Archived May 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carmarthen. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Carmarthen. |

- Carmarthenshire County Council

- Listed buildings

- Historical information and links on GENUKI