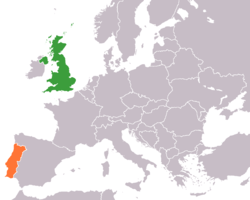

Anglo-Portuguese Alliance

| |

United Kingdom |

Portugal |

|---|---|

The Anglo-Portuguese Alliance (or Aliança Luso-Britânica, "Luso-British Alliance", also known in Portugal as Aliança Inglesa, "English Alliance"), ratified at the Treaty of Windsor in 1386, between England (succeeded by the United Kingdom) and Portugal, may be the oldest alliance in the world that is still in force – with the earliest treaty dating back to the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1373 - although this claim is disputed by some historians who believe the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France, first signed in 1295, may still be in effect.[1]

Historically, the Kingdom of Portugal and the Kingdom of England, and later the modern Portugal and United Kingdom, have never waged war against each other nor have they participated in wars on opposite sides as independent states since the signing of the Treaty of Windsor. While Portugal was subsumed under the Iberian Union, rebellious Portuguese factions and government in exile sought refuge and help in England. England spearheaded the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) on the side of the deposed Portuguese royal house.

The alliance has served both countries throughout their respective military histories, influencing the participation of the United Kingdom in the Iberian Peninsular War, the UK's major land contribution to the Napoleonic Wars and the establishment of an Anglo-American base in Portugal. Portugal aided England (and later the UK) in times of need, for example, in the First World War. Today, Portugal and the United Kingdom are both part of NATO, a larger intergovernmental military alliance between several North American and European states that accounts for over 70% of total global military spending.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Portugal |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Middle Ages

_(late_15th_C)%2C_f.244v_-_BL_Royal_MS_14_E_IV.png)

English aid to the House of Aviz (which ruled Portugal from 1385 to 1580) set the stage for Portuguese cooperation with England that would become a cornerstone of Portugal's foreign policy for more than five hundred years. However, English aid to Portugal went back much further to the 1147 Siege of Lisbon, when English and other northern European crusaders – en route to the Holy Land to participate in the Second Crusade – stopped and helped Portuguese King Afonso Henriques to conquer the city from the Moors. In May 1386, the Treaty of Windsor sealed the alliance - first started in 1294, renewed in the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1373 and confirmed at the Battle of Aljubarrota (1385) - with a pact of perpetual friendship between the two countries. The most important part of the treaty stated that:

It is cordially agreed that if, in time to come, one of the kings or his heir shall need the support of the other, or his help, and in order to get such assistance applies to his ally in lawful manner, the ally shall be bound to give aid and succour to the other, so far as he is able (without any deceit, fraud, or pretence) to the extent required by the danger to his ally’s realms, lands, domains, and subjects; and he shall be firmly bound by these present alliances to do this.[2]

In July 1386, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, son of the late king Edward III of England and father of the future King Henry IV of England, landed in Galicia with an expeditionary force to press his claim to the Crown of Castile with Portuguese aid. He failed to win the support of the Castilian nobility and returned to England with a cash compensation from the rival claimant.

John of Gaunt left behind his daughter, Philippa of Lancaster, to marry King John I of Portugal (February 1387) in order to seal the Anglo-Portuguese alliance. By this marriage, John I became the father of a generation of princes called by the poet Luís de Camões the "Illustrious Generation", which led Portugal into its golden age, during the period of the Discoveries.

Philippa brought to the court the Anglo-Norman tradition of an aristocratic upbringing and gave her children good educations. Her personal qualities were of the highest standard, and she reformed the court and imposed rigid standards of moral behaviour. On the other hand, the more tolerant Portuguese aristocracy saw her methods as too traditional or outdated.

Philippa provided royal patronage for English commercial interests that sought to meet the Portuguese desire for cod and cloth in return for wine, cork, salt, and oil shipped through the English warehouses at Porto. Her eldest son, Duarte, authored moral works and became king in 1433; Pedro, who travelled widely and had an interest in history, became regent (1439-1448) after Duarte died of the plague in 1438; Ferdinand the Saint Prince (1402-1443), who became a crusader, participated in the attack on Tangiers in 1437; and Henrique – also known as Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460) – became the master of the Order of Christ and the instigator and organiser of Portugal's early voyages of discovery.

Disruption

The Iberian Union (1580–1640), a 60-year dynastic union between Portugal and Spain, interrupted the alliance. Portuguese foreign policy became tied to Spanish hostility to England. As a result, Portugal and England were on opposite sides of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) and the Dutch–Portuguese War. The alliance was reconfirmed after the Portuguese Restoration War and the English Restoration.

17th to 19th centuries

_-_Joaquim_Carneiro_da_Silva_(1727-1818).png)

The alliance was reconfirmed after the breakup of the Iberian Union, primarily due to both countries' respective rivalries with Spain, the Netherlands, and France, both in Europe and overseas. During this time, important episodes in the alliance were:

- The War of Spanish Succession, when Portugal together with the Duchy of Savoy initially sided with France, but after the Battle of Blenheim reunited with its ally.

- The Seven Years' War, when Spain invaded Portugal in 1762, Britain intervened as Portugal's ally. Although faced with vastly superior numbers, the Portuguese and British forces together with Portuguese guerrillas defeated the Spanish and French forces, which suffered huge losses.

- The Napoleonic Wars, when Portugal, isolated in a Europe wholly dominated by Napoleon, continued to trade with the United Kingdom despite French restrictions and was finally invaded, but with British help finally regained total sovereignty and independence. The Portuguese royal family at the time (including Prince John, at the time acting as regent for his mother, the aged and mentally impaired Queen Maria I) took refuge in its then vice-royalty of Brazil, under escort by the British fleet.

- The Portuguese civil war, when the United Kingdom gave important support to the Liberal faction.

- The 1890 British Ultimatum was considered by Portuguese historians and politicians at that time to be the most outrageous and infamous action of the British against their oldest ally.[3] The 1890 ultimatum was said to be one of the main causes for the Republican Revolution, which ended the monarchy in Portugal 20 years later.

20th century

During the 20th century, the treaty was invoked several times:

First World War

- After German incursions in Portuguese East Africa (today Mozambique), Portuguese troops fought on the Western Front alongside Allied soldiers during the First World War.[4]

Second World War

- Upon the declaration of war in September 1939, the Portuguese Government announced on 1 September that the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance remained intact, but since the British did not seek Portuguese assistance, Portugal would remain neutral. In an aide-mémoire of 5 September 1939, the British Government confirmed the understanding. British strategists regarded Portuguese non-belligerency as "essential to keep Spain from entering the war on the side of the Axis."[5]

- Britain recognized the important role of the anti-democratic and authoritarian prime minister António de Oliveira Salazar on May 15, 1940, when Douglas Veale, Registrar of the University of Oxford, informed Salazar that the University's Hebdomadal Council had "unanimously decided at its meeting last Monday, to invite you [Salazar] to accept the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Civil Law".[6]

- July 1940: Salazar's decision to stick with the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance allowed the Portuguese island of Madeira to help the Allies: that month, around 2,500 Gibraltar evacuees were shipped to Madeira.[7]

- September 1940: Winston Churchill wrote to Salazar, congratulating him on his ability to keep Portugal out of the war, asserting that "as so often before during the many centuries of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance, British and Portuguese interests are identical on this vital question".[6]

- Samuel Hoare, 1st Viscount Templewood, the British Ambassador in Madrid from 1940 to 1944, recognised Salazar's crucial role in keeping Iberia neutral during the war. Lord Templewood asserted that in his thirty years of political life he had met most of the leading statesmen of Europe and that he placed Salazar very high on the list of those who impressed him. He stated that Salazar "being a man of one idea – the good of his country – he was convinced that the slightest step from the narrow path of neutrality would endanger the work of national regeneration to which he had devoted the whole of his public life". He also affirmed that "Salazar detested Hitler", that the Portuguese régime differed fundamentally from Nazism and Fascism, and that Salazar never left a doubt in his mind that he desired a Nazi defeat.[8]

- During the Second World War, Salazar steered Portugal down a middle path, but nevertheless provided aid to the Allies. The British Ambassador in Lisbon, Ronald Campbell, saw Salazar as fundamentally loyal to the Alliance and stated that "he [Salazar] would answer the call if it were made on grounds of dire necessity". When, in August 1943, the British requested base facilities in the Azores and invoked the alliance that had existed for over 600 years between Portugal and Great Britain,[9] Salazar responded favorably and virtually at once:[10] Portugal granted naval bases on Portuguese territory to Britain, in keeping with the traditional Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, letting them use the Azorean ports of Horta (on the island of Faial) and Ponta Delgada (on the island of São Miguel), and the airfields of Lajes Field (on Terceira Island) and Santana Field (on São Miguel Island).[11]

- In November 1943, the British Ambassador in Lisbon, Sir Ronald Campbell, wrote (paraphrasing Salazar) that "strict neutrality was the price the allies paid for strategic benefits accruing from Portugal's neutrality and that if her neutrality instead of being strict had been more benevolent in our favour Spain would inevitably have thrown herself body and soul into the arms of Germany. If this had happened the Peninsula would have been occupied and then North Africa, with the result that the whole course of the war would have been altered to the advantage of the Axis."[12]

- From November 1943, when the British gained the use of the Azores, to June 1945, 8,689 U.S. aircraft departed from Lajes base in the Azores, including 1,200 B-17 and B-24 bomber aircraft which were ferried across the Atlantic. Cargo aircraft carried vital personnel and equipment to North Africa, to the United Kingdom and – after the Allies gained a foothold in Western Europe – to Orly Field near Paris. Flights returning from Europe carried wounded servicemen. Medical personnel at Lajes, Azores, handled approximately 30,000 air evacuations en route to the United States for medical care and rehabilitation. By using Lajes Field, it was possible to reduce flying time between the United States and North Africa from 70 hours to 40. This considerable reduction in flying hours enabled aircraft to make almost twice as many crossings per month between the United States and North Africa and clearly demonstrated the geographic value of the Azores during the war.

Postwar

- The establishment of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) took place in 1960 following the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957. Portugal and the UK were two of the seven founding members of EFTA. In 1973 the UK left EFTA to join the EEC. Portugal did the same in 1986.

- In 1961, during the Indian invasion of Portuguese India, Portugal sought the help of Britain.

- During the 1982 Falklands War, the facilities of the Azores were again offered to the Royal Navy.

Modern times

Today, as both countries are members of the NATO, their relations are largely coordinated through those institutions, rather than by the bilateral treaty.

See also

Sources

- Hoare, Samuel (1946). Ambassador on Special Mission. UK: Collins; First Edition. pp. 124 and 125.

- Kay, Hugh (1970). Salazar and Modern Portugal. NY, USA: Hawthorn Books.

- Leite, Joaquim da Costa (1998). "Neutrality by Agreement: Portugal and the British Alliance in World War II". 14 (1). American University International Law Review: 185–199. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- Meneses, Filipe (2009). Salazar: A Political Biography. Enigma Books; 1 edition. p. 544. ISBN 978-1929631902.

- Stone, Glyn (1994). The Oldest Ally: Britain and the Portuguese Connection, 1936-1941. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 228. ISBN 9780861932276.

References

- ↑ https://www.manchester.ac.uk/discover/news/franco-scottish-alliance-against-england-one-of-longest-in-history/

- ↑ A. R. Myers, English historical documents. 4. (Late medieval). 1327 - 1485

- ↑ Ferreira Duarte, João (1st semester 2000). "The Politics of Non-Translation: A Case Study in Anglo-Portuguese Relations" (PDF). TTR : traduction, terminologie, rédaction. 13 (1): 95–112. doi:10.7202/037395ar. ISSN 0835-8443. Retrieved 7 August 2018. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "British-Portuguese Alliance". nzhistory. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ↑ Leite 1998, pp. 185-199.

- 1 2 Meneses 2009, p. 240.

- ↑ Mascarenhas, Alice (9 January 2013). "Madeira Gold Medal of Merit for Louis". Gibraltar Chronicle The Independent Daily. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ Hoare 1946, pp. 124-125.

- ↑ Winston Churchill, 12 October 1943 Statement in the House of Commons

- ↑ Kay 1970, p. 123.

- ↑ Kay, p.123

- ↑ Leite, "Document 2: Telegram From Sir Ronald Campbell

![]()