Bosnian Cyrillic

| Bosnian Cyrillic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type |

Alphabet Cyrillic script

|

| Languages | Serbo-Croatian |

Time period | 10th-18th century |

| South Slavic languages and dialects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Western South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Transitional dialects

|

||||||

|

Alphabets |

||||||

Bosnian Cyrillic, widely known as Bosančica[1][2] is an extinct variant of the Cyrillic alphabet that originated in medieval Bosnia.[1] It was widely used in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and the bordering areas of modern-day Croatia (southern and middle Dalmatia and Dubrovnik regions). It was particularly used by the Bosnian Church community. Its name in Serbo-Croatian is bosančica and bosanica[3] the latter of which can be translated as Bosnian script. Serbian scholars consider it as part of variant of Serbian Cyrillic because of a lot of mentions of Bosnian Cyrillic as Serbian letters or Serbian characters in sources among Catholics and Muslims in Bosnia and Southern Dalmatia.[4] Croat scholars also call it Croatian script, Croatian–Bosnian script, Bosnian–Croat Cyrillic, harvacko pismo, arvatica or Western Cyrillic.[5][6] For other names of Bosnian Cyrillic, see below.

The use of Bosančica amongst Bosnians was replaced by Arebica upon the introduction of Islam in Bosnia Eyalet, first amongst the elite, then amongst the wider public.[7] The first book in Bosančica was printed by Frančesko Micalović in 1512 in Venice.[8]

History and characteristic features

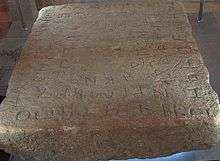

It is hard to ascertain when the earliest features of a characteristic Bosnian type of Cyrillic script had begun to appear, but paleographers consider the Humac tablet (a tablet written in Bosnian Cyrillic[9]) to be the first document of this type of script and is believed[9] to date from the 10th or 11th century[9]. Bosnian Cyrillic was used continuously until the 18th century, with sporadic usage even taking place in the 20th century.

Historically, Bosnian Cyrillic is prominent in the following areas:

- Passages from the Bible in documents of Bosnian Church adherents, 13th and 15th century.

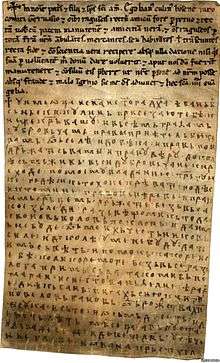

- Numerous legal and commercial documents (charters, letters, donations) of nobles and royalty from medieval Bosnian state in correspondence with the Republic of Ragusa and various cities in Dalmatia (e.g. the Charter of Ban Kulin), beginning in the 12th and 13th centuries, and reaching its peak in the 14th and 15th centuries.

- Tombstone inscriptions on marbles in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina, chiefly between 11th and 15th centuries.

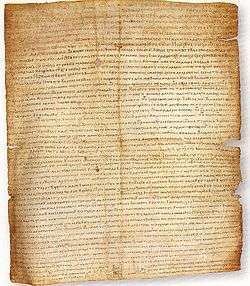

- Legal documents in central Dalmatia, like the Poljica Statute (1440) and other numerous charters from this area; Poljica and neighbourhood Roman Catholic church books used this alphabet until the late 19th century.

- The "Supetar fragment" from the 12th century was found in Sveti Petar u Šumi in central Istria, among the stones of a collapsed southern monastery wall. Until the 15th century it was a Benedictine monastery and later a Pauline monastery. This finding could indicate that Bosančica spread all the way to Istria and Kvarner Gulf.

- The Roman Catholic diocese in Omiš had a seminary (called arvacki šeminarij, "Croat seminary") active in the 19th century, in which arvatica letters were used.

- Liturgical works (missals, breviaries, lectionaries) of the Roman Catholic Church from Dubrovnik, 15th and 16th century - the most famous is a printed breviary from 1512[10][11][12]

- The comprehensive body of Bosnian literacy, mainly associated with the Franciscan order, from the 16th to mid-18th century and early 19th century. This is by far the most abundant corpus of works written in Bosnian Cyrillic, covering various genres, but belonging to the liturgical literature: numerous polemical tractates in the spirit of the Counter-Reformation, popular tales from the Bible, catechisms, breviaries, historical chronicles, local church histories, religious poetry and didactic works. Among the most important writings of this circle are works of Matija Divković, Stjepan Matijević and Pavao Posilović.

- After the Ottoman conquest, Bosnian Cyrillic was used, along with Arebica, by the Bosnian Muslim nobility, chiefly in correspondence, mainly from the 15th to 17th centuries (hence, the script has also been called begovica, "bey's script"). Isolated families and individuals could write in it even in the 20th century.

In conclusion, main traits of Bosnian Cyrillic include:

- It was a form of Cyrillic script mainly in use in Bosnia and Herzegovina, central Dalmatia and Dubrovnik.

- Its earliest monuments are from the 11th century, but the golden epoch covered the period from the 14th to 17th centuries. From the late 18th century it rather speedily fell into disuse to be replaced by the Latin script.

- Its primary characteristics (scriptory, morphological, orthographical) show strong connection with the Glagolitic script, unlike the standard Church Slavonic form of Cyrillic script associated with Eastern Orthodox churches.[13]

- It had been in use, in ecclesiastical works, mainly in Bosnian Church and Roman Catholic Church in historical lands of Bosnia, Herzegovina, Dalmatia and Dubrovnik. Also, it was a widespread script in Bosnian Muslim circles, which, however, preferred modified Arabic aljamiado script. Serbian Orthodox clergy and adherents used mainly the standard Serbian Cyrillic of the Resava orthography.[13]

- The form of Bosnian Cyrillic has passed through a few phases, so although culturally it is correct to speak about one script, it is evident that features present in Bosnian Franciscan documents in the 1650s differ from the charters from Brač island in Dalmatia in the 1250s.

Controversies and polemic

The polemic about "ethnic affiliation" of Bosnian Cyrillic started in the 19th century, then reappeared in the mid-1990s.[14] Without going into nuances and details, the polemic about attribution and affiliation of Bosnian Cyrillic texts seems to rest on further arguments:

- Serbian scholars claim that it is just a variant of Serbian Cyrillic; actually, a "minuscle", or Italic (cursive) script devised at the court of Serbian king Stefan Dragutin.[15] Accordingly, Bosnian Cyrillic texts also belong to the Serbian literary corpus. Some consider that a strong argument in favour of the Serbian side is the fact that there are a lot of mentions of Bosnian Cyrillic as "Serbian letters"[4] or "Serbian characters"[16] among Catholics (in Bosnia and Dubrovnik) and Muslims.[15] The main Serbian authorities in the field are Jorjo Tadić, Vladimir Ćorović, Petar Kolendić, Petar Đorđić, Vera Jerković, Irena Grickat, Pavle Ivić and Aleksandar Mladenović.

- The Croatian side is split. One school of paleography basically challenges the letters being Serbian. It claims that majority of the most important documents of Bosnian Cyrillic had been written either before any innovations devised at the Serbian royal court happened, or did not have any historical connection with it whatsoever- that the Serbian claims on the origin of Bosnian Cyrillic are unfounded, and the script, since belonging to the Croatian cultural sphere should be called not Bosnian, but Croatian Cyrillic.[15] Another school of Croatian philologists acknowledges that "Serbian connection", as exemplified in variants present at the Serbian court of king Dragutin, did influence Bosnian Cyrillic- but, they aver, it was just one strand, since scriptory innovations have been happening both before and after the mentioned one. First school insists that all Bosnian Cyrillic texts belong to the corpus of Croatian literacy, and the second school that all texts from Croatia and only a part from Bosnia and Herzegovina are to be placed into Croatian literary canon (they exclude c. half of Bosnian Christian texts, but include all Franciscan and the majority of legal and commercial documents). Also, the second school generally uses the name Western Cyrillic instead of Croatian Cyrillic (or Bosnian Cyrillic, for that matter). Both schools mention that various sources, both Croatian and other European (German, Italian,..) call this script "Croatian letters" or "Croatian script". The main Croatian authorities in the field are Vatroslav Jagić, Mate Tentor, Ćiro Truhelka, Vladimir Vrana, Jaroslav Šidak, Herta Kuna, Tomislav Raukar, Eduard Hercigonja and Benedikta Zelić-Bučan.

- Bosniak scholars unisonally dismiss any claims of Croat or Serb affiliation, instead maintaining the Bosnian Cyrillic as ethnically Bosnian and, consequently, Bosniak, in legacy of medieval Bosnia and the native Bosnian Church.[17]

- Yugoslav Serbian scholars concluded that Bosančica was a term introduced through Austro-Hungarian propaganda. They regarded it a type of cursive Cyrillic script,[18] without specifics that would warrant an "isolation from Cyrillic".[19]

- Russian philologist A. I. Sobolevsky (1856–1929) regarded it Serbian.[20]

The irony of the contemporary status of Bosnian Cyrillic is as follows: scholars are still trying to prove that Bosnian Cyrillic is ethnically their own, while simultaneously relegating the corpus of Bosnian Cyrillic written texts to the periphery of national culture. This extinct form of Cyrillic is peripheral to Croatian paleography which focuses on Glagolitic and Latin script corpora.

Legacy

In 2015, a group of artists started a project called "I write to you in Bosancica" which involved art and graphic design students from Banja Luka, Sarajevo, Široki Brijeg, and Trebinje. Exhibitions of the submitted artworks will be held in Sarajevo, Trebinje, Široki Brijeg, Zagreb, and Belgrade.[21] The purpose of the project was to resurrect the ancient script and show the "common cultural past" of all the groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The first phase of the project was to reconstruct all of the ancient characters by using ancient, handwritten documents.

Names

Names used in scholarship and literature (chronological order, recent first):

- zapadna (bosanska) ćirilica, by Croatian linguist Stjepan Ivšić (1884–1962)

- poljičica, poljička azbukvica, among the people of Poljica and Frane Ivanišević (1863−1947)[22]

- srbskoga slovi ćirilskimi and bosansko-dalmatinska ćirilica (Bosnian-Dalmatian Cyrillic), by Croatian linguist Vatroslav Jagić (1838–1923)[23][24]

- bosanska ćirilica ("Bosnian Cyrillic"), by Croatian historian and Catholic priest Franjo Rački (1828–1894)

- hrvatsko-bosanska ćirilica ("Croatian-Bosnian Cyrillic"), by Croatian historian and politician Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski (1816–1889)

- bosanica ("Bosnian [script]"), by Stipan Zlatić[23]

- bosanska azbukva ("Bosnian alphabet"), by Catholic priest Ivan Berčić (1824–1870)

- (Bosnian-Catholic alphabet), by Franciscan writer Ivan Franjo Jukić (1818–1857)[23]

- (Bosnian or Croatian Cyrillic alphabet), by Slovene linguist Jernej Kopitar (1780–1844)[23]

- bosanska brzopisna grafija ("Bosnian cursive graphics"), by E. F. Karskij

- zapadna varijanta ćirilskog brzopisa ("Western variant of Cyrillic cursive"), by Petar Đorđić

- stara srbija (meaning "Old Serbia"), term used by the notable Ottoman Bosnian frontier lords, the Kulenovići, to denote their script (bosančica).[25]

- serbski ("Serbian"), term used by Croatian writer Matija Antun Reljković (1732–1798) in his work Satir[26]

- s'rpski ("Serbian"), by fra Antun Depope (fl. 1625–30)

- sarpski ("Serbian"), term used by Bosnian Franciscan writer Matija Divković (1563–1631) in his work Nauk karstianski, printed in 1616[27]

Gallery

Humac tablet (10th–11th century)

Humac tablet (10th–11th century) Charter of Ban Kulin of Bosnia (12th century)

Charter of Ban Kulin of Bosnia (12th century) Batalo's Gospel (1393)

Batalo's Gospel (1393) Poljica Statute (1400)

Poljica Statute (1400)- Document from Brač

See also

References

- Notes

- 1 2 Balić, Smail (1978). Die Kultur der Bosniaken, Supplement I: Inventar des bosnischen literarischen Erbes in orientalischen Sprachen. Vienna: Adolf Holzhausens, Vienna. pp. 49–50, 111.

- ↑ Algar, Hamid (1995). The Literature of the Bosnian Muslims: a Quadrilingual Heritage. Kuala Lumpur: Nadwah Ketakwaan Melalui Kreativiti. pp. 254–68.

- ↑ Popovic, Alexandre (1971). La littérature ottomane des musulmans yougoslaves: essai de bibliographie raisonnée, JA 259. Paris: Alan Blaustein Publishing House. pp. 309–76.

- 1 2 Franc Mikloshich - Monumenta Serbica - Povelja Stjepana Kotromanića od 15. februara 1333.,.

- ↑ Prosperov Novak & Katičić 1987, p. 73.

- ↑ Superčić & Supčić 2009, p. 296.

- ↑ Dobrača, Kasim (1963). Katalog arapskih, turskih i perzijskih rukopisa (Catalogue of the Arabic, Turkish and Persian Manuscripts in the Gazi Husrev-beg Library, Sarajevo). Sarajevo. pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Bošnjak, Mladen (1970). Slavenska inkunabulistika. Mladost. p. 26.

Najstarija do sada poznata djela tiskana su tim pismom u izdanju Dubrovcanina Franje Micalovic Ratkova

- 1 2 3 "Srećko M. Džaja vs. Ivan Lovrenović – polemika o kulturnom identitetu BiH Ivan Lovrenović". ivanlovrenovic.com (in Croatian). Polemics appeared between Srećko M. Džaja & Ivan Lovrenović in Zagreb's biweekly "Vijenac", later in whole published in Journal of Franciscan theology in Sarajevo, "Bosna franciscana" No.42. 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ Susan Baddeley; Anja Voeste (2012). Orthographies in Early Modern Europe. Walter de Gruyter. p. 275. ISBN 9783110288179. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

[...] the first printed book in Cyrillic (or, to be more precise, in Bosančica) [...] (Dubrovnik Breviary of 1512; cf. Rešetar and Đaneli 1938: 1-109).[25]

- ↑ Jakša Ravlić, ed. (1972). Zbornik proze XVI. i XVII. stoljeća. Pet stoljeća hrvatske književnosti (in Croatian). 11. Matica hrvatska - Zora. p. 21. UDC 821.163.42-3(082). Retrieved 2013-01-24.

Ofičje blažene gospođe (Dubrovački molitvenik iz 1512.)

- ↑ Cleminson, Ralph (2000). Cyrillic books printed before 1701 in British and Irish collections: a union catalogue. British Library. p. 2. ISBN 9780712347099.

2. Book of Hours, Venice, Franjo Ratković, Giorgio di Rusconi, 1512 (1512.08.02)

- 1 2 ILIEV, IVAN G. "SHORT HISTORY OF THE CYRILLIC ALPHABET | IVAN G. ILIEV | IJORS International Journal of Russian Studies". www.ijors.net. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ Tomasz Kamusella (15 January 2009). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 976. ISBN 978-0-230-55070-4.

- 1 2 3 ILIEV, IVAN G. "SHORT HISTORY OF THE CYRILLIC ALPHABET | IVAN G. ILIEV | IJORS International Journal of Russian Studies". www.ijors.net. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN STUDIES. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ http://novi.ba/clanak/72326/vuk-bacanovic-srpski-bosanski-i-bosnjacki-for-dummies

- ↑ Jahić, Dževad; Halilović, Senahid; Palić, Ismail (2000). Gramatika bosanskoga jezika (PDF). Zenica: Dom štampe. p. 49. ISBN 9789958420467. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ Prilozi za književnost, jezik, istoriju i folklor. 22–23. Belgrade: Državna štamparija. 1956. p. 308.

- ↑ Književnost i jezik. 14. 1966. pp. 298–302.

- ↑ Соболевский А. И. (15 March 2013). Славяно-русская палеография. Directmedia. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-5-4460-2375-2.

- ↑

- ↑ Poljička glagoljica ili poljiška azbukvica

- 1 2 3 4 Journal of Croatian Studies. 10. Croatian Academy of America. 1986. p. 133.

- ↑ Jagić, Vatroslav (1867). Historija književnosti naroda hrvatskoga i srbskoga. Knj.l.Staro doba,, Opseg 1. Zagreb: Štamparija Dragutina Albrechta. p. 142. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ Vladimir Ćorović (1925), Bosna i Hercegovina

Čuveni krajiški begovi Kulenovići [...] Njihovo pismo bilo je sve do okupacije ćirilica, takozvano begovsko pismo, koje su oni sami zvali stara srbija.

- ↑ Matija Antun Reljković (1974) [17xx], Ivo Bogner, ed., Satir iliti divji čovik

- ↑ Ivan Franjo Jukić, ed. (1850). "V. Književnost bosanska". Bosanski prijatelj. Zagreb: Ljudevit Gaj. 1: 29.

Plač blažene divice Marie, koi plač izpisavši sarpski... fra Matie Divković iz Ielašak...

- Bibliography

- Domljan, Žarko, ed. (2006). Omiš i Poljica. Naklada Ljevak. ISBN 953-178-733-6.

- Mimica, Bože (2003). Omiška krajina Poljica makarsko primorje: Od antike do 1918. godine. ISBN 953-6059-62-2.

- Prosperov Novak, Slobodan; Katičić, Radoslav, eds. (1987). Dva tisućljeća pismene kulture na tlu Hrvatske [Two thousand years of writing in Croatia]. Sveučilišna naklada Liber: Muzejski prostor. ISBN 863290101X.

- Superčić, Ivan; Supčić, Ivo (2009). Croatia in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance: A Cultural Survey. Philip Wilson Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85667-624-6.