Montenegrin language

| Montenegrin | |

|---|---|

| црногорски / crnogorski | |

| Pronunciation | [tsr̩nǒɡorskiː] |

| Native to | Montenegro |

| Ethnicity | Montenegrins |

Native speakers | 232,600[1] (2011) |

|

Cyrillic (Montenegrin alphabet) Latin (Montenegrin alphabet) Yugoslav Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Montenegro |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Board for Standardization of the Montenegrin Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

cnr [4] |

| ISO 639-3 |

cnr [5] |

| Linguasphere |

part of 53-AAA-g |

| South Slavic languages and dialects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Western South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Transitional dialects

|

||||||

|

Alphabets |

||||||

Montenegrin (/ˌmɒntɪˈniːɡrɪn/; црногорски / crnogorski) is the normative variety of the Serbo-Croatian language mainly used by Montenegrins and the official language of Montenegro. Montenegrin is based on the most widespread dialect of Serbo-Croatian, Shtokavian, more specifically on Eastern Herzegovinian, which is also the basis of Standard Croatian, Serbian, and Bosnian.[6]

Montenegro's language has historically and traditionally been called Serbian.[7] The idea of a Montenegrin standard language separate from Serbian appeared in the 1990s during the breakup of Yugoslavia, through proponents of Montenegrin independence from Serbia. Montenegrin became the official language of Montenegro with the ratification of a new constitution on 22 October 2007.

The Montenegrin standard is still emerging. Its orthography was established on 10 July 2009 with the addition of two letters to the alphabet. Their usage remained controversial and they achieved only limited public acceptance, along with some proposed alternative spellings.[8] They had been used for official documents since 2009, but in February 2017, the Assembly of Montenegro removed them from any type of governmental documentation.[9]

Language standardization

In January 2008, the government of Montenegro formed the Council for the Codification of the Montenegrin Language, which aims to standardize the Montenegrin language according to international norms. Proceeding documents will, after verification, become a part of the educational programme in Montenegrin schools.

The first Montenegrin standard was officially proposed in July 2009. In addition to the letters prescribed by the Serbo-Croatian standard, the proposal introduced two additional letters, ⟨ś⟩ and ⟨ź⟩, to replace the digraphs ⟨sj⟩ and ⟨zj⟩.[10] The Ministry of Education has accepted neither of the two drafts by the Council for the Standardization of the Montenegrin language, but instead adopted an alternate third one which was not a part of their work. The Council has criticized this act, saying it comes from "a small group" and that it contains an abundance of "methodological, conceptual and linguistic errors".[11]

On 21 June 2010, the Council for General Education adopted the first Montenegrin Grammar.

First written request for the assignment of international code was submitted to the technical committee ISO 639 in July 2008. Complete paperwork was forwarded to Washington in September 2015. After the long procedure, the request was finally approved on Friday, December 8, 2017 and ISO 639-2 and -3 code [cnr] was assigned to the Montenegrin language, effective December 21, 2017.[4][5][12]

Official status and speakers' preference

The language remains an ongoing issue in Montenegro.[13]

In the previous census of 1991, the vast majority of Montenegrin citizens, 510,320 or 82.97%, declared themselves speakers of the then official language: Serbo-Croatian. The 1981 population census also recorded a Serbo-Croatian-speaking majority. However, in the first Communist censuses, the vast majority of the population declared Serbian their native language. Such is also the case with the first recorded population census in Montenegro in 1909, when approximately 95% of the population of the Principality of Montenegro declared Serbian their native language. According to the Constitution of Montenegro, the official language of the republic since 1992 is Serbian of the Ijekavian standard.

After World War II and until 1992, the official language of Montenegro was Serbo-Croatian. Before that, in the previous Montenegrin realm, the language in use was called Serbian. The Serbian language was the officially used language in Communist Montenegro until after the 1950 Novi Sad Agreement, and Serbo-Croatian was introduced into the Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro in 1974. In the late 1990s and early 21st century, organizations promoting Montenegrin as a distinct language appeared only since 2004 when the Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro regime introduced the term to usage. The new constitution, adopted on 19 October 2007, deemed Montenegrin to be the official language of Montenegro.

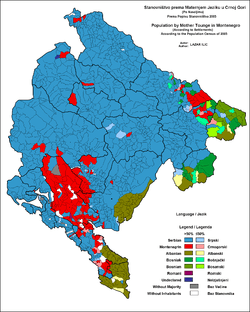

The most recent population census conducted in Montenegro was in 2011. According to it, 36.97% of the population (229,251) declared Montenegrin their native language, and 42.88% (265,895) declared Serbian their native language.[14]

Mijat Šuković, a prominent Montenegrin lawyer, wrote a draft version of the constitution which passed the parliament's constitutional committee. Šuković suggested Montenegrin as the official language of Montenegro. The Venice Commission, an advisory body of the Council of Europe, had a generally positive attitude towards the draft of the constitution but did not address the language and church issues, calling them symbolic. The new constitution was ratified on 19 October 2007, declaring Montenegrin as the official language of Montenegro, as well as recognising Albanian, Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian.

The ruling Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro and Social Democratic Party of Montenegro stand for nothing but plainly renaming the country's official language into Montenegrin, meeting opposition from the Socialist People's Party of Montenegro, the People's Party, the Democratic Serb Party, the Bosniak Party, the Movement for Changes as well as the Serb List coalition led by the Serb People's Party. However, a referendum was not needed, as a two-thirds majority of the parliament voted for the Constitution, including the ruling coalition, Movement for Changes, the Bosniaks and the Liberals, while the pro-Serbian parties voted against it and the Albanian minority parties abstained from voting. The Constitution was ratified and adopted on 19 October 2007, recognizing Montenegrin as the official language of Montenegro.

According to a poll of 1,001 Montenegrin citizens conducted by Matica crnogorska in 2014, linguistic demographics were:[15]

- 41.1% Montenegrin

- 39.1% Serbian

- 12.3% Serbian, Montenegrin, Bosnian, Croatian and Serbo-Croatian are one and the same

- 3.9% Serbo-Croatian

- 1.9% Bosnian

- 1.7% Croatian

According to an early 2017 poll, 42.6% of Montenegro's citizens have opted for Serbian as the name of their native language, while 37.9% for Montenegrin.[16]

Note that not only Montenegrins by ethnicity declare Montenegrin as their native language. According to the 2011 census, other ethnic groups in Montenegro have also declared their language Montenegrin by a certain percentage. Most openly, Matica Muslimanska called on Muslims living in Montenegro to name their native language as Montenegrin.[17]

Linguistic considerations

Montenegrins speak Shtokavian subdialects of Serbo-Croatian, some which are shared with the neighbouring Slavic nations:

- Eastern Herzegovinian dialect (in the west and northwest).

- Zeta-Raška dialect (spoken in the rest of the country).

Montenegrin alphabet

The proponents of the separate Montenegrin language prefer using the Latin alphabet over the Cyrillic alphabet. In both alphabets there are two additional letters (bold), which are easier to render in digital typography in the Latin alphabet due to their existence in Polish, but which must be created ad hoc using combining characters when using Cyrillic.

| Latin | A | B | C | Č | Ć | D | Dž | Đ | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | Lj | M | N | Nj | O | P | R | S | Š | Ś | T | U | V | Z | Ž | Ź |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyrillic | А | Б | Ц | Ч | Ћ | Д | Џ | Ђ | Е | Ф | Г | Х | И | Ј | К | Л | Љ | М | Н | Њ | О | П | Р | С | Ш | Ć | Т | У | В | З | Ж | З́ |

| Cyrillic | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Ђ | Е | Ж | З | З́ | И | Ј | К | Л | Љ | М | Н | Њ | О | П | Р | С | Ć | Т | Ћ | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Џ | Ш |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin | A | B | V | G | D | Đ | E | Ž | Z | Ź | I | J | K | L | Lj | M | N | Nj | O | P | R | S | Ś | T | Ć | U | F | H | C | Č | Dž | Š |

Grammar

Literature

Many literary works of authors from Montenegro provide examples of the local Montenegrin vernacular. The medieval literature was mostly written in Old Church Slavonic and its recensions, but most of the 19th century works were written in some of the dialects of Montenegro. They include the folk literature collected by Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and other authors, as well as the books of writers from Montenegro such as Petar Petrović Njegoš's The Mountain Wreath (Gorski vijenac), Marko Miljanov's The Examples of Humanity and Bravery (Primjeri čojstva i junaštva), etc. In the second half of the 19th century and later, the Eastern Herzegovinian dialect, which served as a basis for the standard Serbo-Croatian language, was often used instead of the Zeta–South Raška dialect characteristic of most dialects of Montenegro. Petar Petrović Njegoš, one of the most respectable Montenegrin authors, changed many characteristics of the Zeta–South Raška dialect from the manuscript of his Gorski vijenac to those proposed by Vuk Stefanović Karadžić as a standard for the Serbian language.

For example, most of the accusatives of place used in the Zeta–South Raška dialect were changed by Njegoš to the locatives used in the Serbian standard. Thus the stanzas "U dobro je lako dobar biti, / na muku se poznaju junaci" from the manuscript were changed to "U dobru je lako dobar biti, / na muci se poznaju junaci" in the printed version. Other works of later Montenegrin authors were also often modified to the East Herzegovinian forms in order to follow the Serbian language literary norm. However, some characteristics of the traditional Montenegrin Zeta–South Raška dialect sometimes appeared. For example, the poem Onamo namo by Nikola I Petrović Njegoš, although it was written in the East Herzegovinian Serbian standard, contains several Zeta–South Raška forms: "Onamo namo, za brda ona" (accusative, instead of instrumental case za brdima onim), and "Onamo namo, da viđu (instead of vidim) Prizren", and so on.

Language politics

Most mainstream politicians and other proponents of the Montenegrin language state that the issue is chiefly one of self-determination and the people's right to call the language what they want, rather than an attempt to artificially create a new language when there is none. The Declaration of the Montenegrin PEN Center[18] states that the "Montenegrin language does not mean a systemically separate language, but just one of four names (Montenegrin, Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian) by which Montenegrins name their part of [the] Shtokavian system, commonly inherited with Muslims, Serbs and Croats". The introduction of the Montenegrin language has been supported by other important academic institutions such as the Matica crnogorska, although meeting opposition from the Montenegrin Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Some proponents go further. The chief proponent of Montenegrin is Zagreb-educated Dr. Vojislav Nikčević, professor at the Department of Language and Literature at the University of Montenegro and the head of the Institute for Montenegrin Language in the capital Podgorica. His dictionaries and grammars were printed by Croatian publishers since the major Montenegrin publishing houses such as Obod in Cetinje opted for the official nomenclature specified in the Constitution (Serbian until 1974, Serbo-Croatian to 1992, Serbian until 2007).[19] Nikčević advocates amending the Latin alphabet with three letters Ś, Ź, and З and corresponding Cyrillic letters С́, З́ and Ѕ (representing IPA [ɕ], [ʑ] and [dz] respectively).[20]

Opponents acknowledge that these sounds can be heard by many Montenegrin speakers, however, they do not form a language system and thus are allophones rather than phonemes.[21] In addition, there are speakers in Montenegro who do not utter them and speakers of Serbian and Croatian outside of Montenegro (notably in Herzegovina and Bosanska Krajina) who do. In addition, introduction of those letters could pose significant technical difficulties (the Eastern European character encoding ISO/IEC 8859-2 does not contain the letter З, for example, and the corresponding letters were not proposed for Cyrillic).

Montenegro's current prime minister Milo Đukanović declared his open support for the formalization of the Montenegrin language by declaring himself as a speaker of Montenegrin in an October 2004 interview with Belgrade daily Politika. Official Montenegrin government communiqués are given in English and Montenegrin on the government's webpage.[22]

In 2004, the government of Montenegro changed the school curriculum so that the name of the mandatory classes teaching the language was changed from "Serbian language" to "Mother tongue (Serbian, Montenegrin, Croatian, Bosnian)". This change was made, according to the government, in order to better reflect the diversity of languages spoken among citizens in the republic and to protect human rights of non-Serb citizens in Montenegro who declare themselves as speakers of other languages.[23]

This decision resulted in a number of teachers declaring a strike and parents refusing to send their children to schools.[24] The cities affected by the strike included Nikšić, Podgorica, Berane, Pljevlja and Herceg Novi.

The new letters had been used for official documents since 2009, but in February 2017, the Assembly of Montenegro removed them from any type of governmental documentation.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Including 229,251 in Montenegro (36.97%), 2,519 in Serbia, 876 in Croatia.

- ↑ B92: Crnogorski jezik u Malom Iđošu (Montenegrin language in Mali Iđoš) (in Serbian)

- ↑ Council of Europe: (in English)

- 1 2 https://www.loc.gov/standards/iso639-2/php/code_list.php

- 1 2 http://www-01.sil.org/iso639-3/documentation.asp?id=cnr

- ↑ Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Or Montenegrin? Or Just 'Our Language'?, Radio Free Europe, February 21, 2009

- ↑ cf. Roland Sussex, Paul Cubberly, The Slavic Languages, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006; esp. v. pp. 73: "Serbia had used Serbian as an official language since 1814, and Montenegro even earlier.".

- ↑ "CG: Niko neće crnogorska slova". Večernje Novosti. 1 October 2013.

- 1 2 "Crnogorska skupština odustala od upotrebe slova ś i ź". Sputnik News Serbia. 2 February 2017.

- ↑ "Dva nova slova u crnogorskom pravopisu". Worldwide.rs. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ↑

- ↑ http://senat.me/en/montenegrin-language-iso-code-cnr-approved/

- ↑ "Montenegro embroiled in language row". BBC News Online. 2010-02-19. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- ↑ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). Monstat. pp. 10, 12. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Pobjeda". Pobjeda.me. Archived from the original on 2014-10-22. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ↑ http://www.vijesti.me/vijesti/u-crnoj-gori-za-sfrj-zali-63-odsto-gradana-928817

- ↑ Ostanimo ono što smo vjekovima bili

Budimo ono što jesmo: Nacionalnost- Musliman, Vjeroispovijest - islamska; Maternji jezik - crnogorski; Državljanstvo - crnogorsko - ↑ "Declaration of Montenegrin P.E.N. Centre". Montenet.org. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ↑ Pravopis crnogorskog jezika, Vojislav Nikčević. Crnogorski PEN Centar, 1997

- ↑ "Language: Montenegrin Alphabet". Montenet.org. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ↑ Politika: Црногорци дописали Вука

- ↑ Archived February 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Slobodan Backović potpisao odluku o preimenovanju srpskog u maternji jezik, Voice of America, 26 March 2004

- ↑ (in Serbian) "Počelo otpuštanje profesora srpskog", Glas Javnosti, 17 September 2004.

Further reading

- Arsenić, Violeta (4 March 2000), "Govorite li crnogorski?" [Do you speak Montenegrin?], Vreme (in Serbo-Croatian) (478), retrieved 4 September 2012

- Glušica, Rajka (2011). "O nacionalizmu u jeziku: prikaz knjige Jezik i nacionalizam" [On nationalism in the language: Review of the book Jezik i nacionalizam] (PDF). Riječ (in Serbo-Croatian). 5: 185–191. ISSN 0354-6039. ZDB-ID 1384597-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2013. (COBISS-CG).

- Ivić, Pavle, "Standard Language as an Instrument of Culture and the Product of National History", Serbian Unity Congress, archived from the original on 16 April 2009

- Kordić, Snježana (2008). "Crnogorska standardna varijanta policentričnog standardnog jezika" [Montenegrin standard variety of a polycentric standard language] (PDF). In Ostojić, Branislav. Jezička situacija u Crnoj Gori – norma i standardizacija: radovi sa međunarodnog naučnog skupa, Podgorica 24.-25.5.2007 (in Serbo-Croatian). Podgorica: Crnogorska akademija nauka i umjetnosti. pp. 35–47. ISBN 978-86-7215-207-4. OCLC 318462699. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2015. (COBISS-CG).

- Lajović, Vuk (24 July 2012). "Političari prodaju maglu" [Politicians are blowing smoke] (PDF) (in Serbo-Croatian). Podgorica: Vijesti. ISSN 1450-6181. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Ramusović, Aida (16 April 2003), "What Language Do Montenegrins Speak?", Transitions Online (subscription required)

External links

| Montenegrin language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Montenegrin language. |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Montenegrin. |

| For a list of words relating to Montenegrin language, see the Montenegrin language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "A Brief Note on the Effect of Montenegrin Independence on Language" (PDF), Permanent Committee on Geographical Names, October 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2012, retrieved 4 September 2012

- Language on Montenegrina