Souq

A souq or souk (Arabic: سوق, Hebrew: שוק shuq, Armenian: շուկա shuka, Spanish: zoco, also spelled shuk, shooq, soq, esouk, succ, suk, sooq, suq, soek) is a marketplace or commercial quarter in Western Asian, North African and some Horn African cities (Amharic: ሱቅ sooq) .[1][2] The term souq goes by many alternative in different parts of the world; in the Balkans, the term bedesten is used; in Malta the terms suq and sometimes monti are used for a marketplace; and in northern Morocco, the Spanish corruption socco is often used. The equivalent Persian term is "bazaar". In general a souq is synonymous with a bazaar or marketplace, and the term souq is used in Arabic speaking countries.

Evidence for the existence of souqs dates to the 6th century BCE. Initially souqs were located outside city walls, but as cities became more populated, souqs were moved to the city centre and became covered walkways. Detailed analysis of the evolution of souqs is scant due to the lack of archaeological evidence.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Western interest in Oriental culture led to the publication of many books about daily life in Middle Eastern countries. Souqs, bazaars and the trappings of trade feature prominently in paintings and engravings, works of fiction and travel writing. Shopping at souq or bazaar is a standard part of daily life throughout the Middle East. Today, souqs tend to be found in a city's medina (old quarter) and are often important tourist attractions.

Etymology and usage

.jpg)

The Arabic word is a loan from Aramaic "šūqā" (“street, market”), itself a loanword from the Akkadian "sūqu" (“street”, from "sāqu", meaning “narrow”). The spelling souk entered European languages probably through French during the French occupation of the Arab countries Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia in the 19th and 20th centuries. Thus, the word "souq" most likely refers to Arabic/North African traditional markets. Other spellings of this word involving the letter "Q" (sooq, souq, so'oq...) were likely developed using English and thus refer to Western Asian/Arab traditional markets, as British colonialism was present there during the 19th and 20th centuries.

In Modern Standard Arabic the term al-sooq refers to markets in both the physical sense and the abstract economic sense (e.g., an Arabic-speaker would speak of the sooq in the old city as well as the sooq for oil, and would call the concept of the free market السوق الحرّ as-sūq al-ḥurr). In northern Morocco, the Spanish corruption socco is often used as in the Grand Socco and Petit Socco of Tangiers. In the sub-continent, a different corruption, 'chowk', is often used in place of souq. The term is often used generically to designate the market in any Western Asian city, but may also be used in Western cities, particularly those with a Muslim community.

History

Documentary sources point to permanent marketplaces in Middle Eastern cities from as early as 550 BCE.[3] A souq was originally an open-air marketplace. Historically, souqs were held outside cities at locations where incoming caravans stopped and merchants displayed their goods for sale. Souqs were established at caravanserai, places where a caravan or caravans arrived and remained for rest and refreshments. Since this might be infrequent, souqs often extended beyond buying and selling goods to include major festivals involving various cultural and social activities. Any souq may serve a social function as being a place for people to meet in, in addition to its commercial function.[4] These souqs or bazaars formed networks, linking major cities with each other in which goods, culture, people and information could be exchanged.[5]

From around the 10th century, as major cities increased in size, the souq or marketplace shifted to the center of urban cities where it spread out along the city streets, typically in a linear pattern.[6] Around this time, permanent souqs also became covered marketplaces.[7]

In tribal areas, where seasonal souks operated, neutrality from tribal conflicts was usually declared for the period of operation of a souq to permit the unhampered exchange of surplus goods. Some of the seasonal markets were held at specific times of the year and became associated with particular types of produce such as Suq Hijr in Bahrain, noted for its dates while Suq 'Adan was known for its spices and perfumes. In spite of the centrality of the Middle Eastern market place, relatively little is known due to the lack of archaeological evidence.[8]

Types

- Souqs

Sibil El-Bed Vieh (Souk-el-Selak), Cairo, Egypt

Sibil El-Bed Vieh (Souk-el-Selak), Cairo, Egypt

Souq in Tunis

Souq in Tunis- Souq El Mushir Street Tripoli

Souk Khan El-Khalili Street (شارع خان الخليلي), Cairo, Egypt

Souk Khan El-Khalili Street (شارع خان الخليلي), Cairo, Egypt- A Syrian man wearing traditional clothes serving Liquorice juice in Homs Market

- The traditional tagine clay pot, used to cook tajine (dish)

- Souq in Marrakesh

- Souq of Marrakesh

Seasonal

.jpg)

A temporary, seasonal souq is held at a set time that might be yearly, monthly or weekly. The oldest souqs were set up annually, and were typically general festivals held outside cities. For example, Souq Ukadh was held yearly in pre-Islamic times in an area between Mecca and Ta’if during the sacred month of Dhu al-Qi'dah. While a busy market, it was more famous for its poetry competitions, judged by prominent poets such as Al-Khansa and Al-Nabigha. An example of an Islamic annual souq is Al Mirbid just outside Basra, also famed for its poetry competitions in addition to its storytelling activities.[9] Temporary souqs tended to become known for specific types of produce. For example, Suq Hijr in Bahrain was noted for its dates while Suq 'Adan was known for its spices and perfumes.[10] Political, economic and social changes have left only the small seasonal souqs outside villages and small towns, primarily selling livestock and agricultural products.

Weekly markets have continued to function throughout the Arab world. Most of them are named from the day of the week on which they are held. They usually have open spaces specifically designated for their use inside cities. Examples of surviving markets are the Wednesday Market in Amman that specializes in the sale of used products, the Ghazl market held every Friday in Baghdad specializing in pets; the Fina’ Market in Marrakech offers performance acts such as singing, music, acrobats and circus activities.

Permanent

Permanent souqs are more commonly occurring, but less renowned as they focus on commercial activity, not entertainment. Until the Umayyad era, permanent souqs were merely an open space where merchants would bring in their movable stalls during the day and remove them at night; no one had a right to specific pitch and it was usually first-come first-served. During the Umayyad era the governments tarted leasing, and then selling, sites to merchants. Merchants then built shops on their sites to store their goods at night. Finally, the area comprising a souq might be roofed over. With its long and narrow alleys, al-Madina Souq is the largest covered historic market in the world, with an approximate length of 13 kilometers.[11] Al-Madina Souq is part of the Ancient City of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986.[12]

- Souq entrance in Jerusalem

Spice Market, Marrakesh

Spice Market, Marrakesh Ouarzazate souq.

Ouarzazate souq..jpg) Covered souqs in Bur Dubai

Covered souqs in Bur Dubai Souq in Tripoli

Souq in Tripoli Leather goods store at the souq in Marrakesh

Leather goods store at the souq in Marrakesh.jpg) Souq in Rabat, Morocco

Souq in Rabat, Morocco Assad souq, Syria, 2001

Assad souq, Syria, 2001 Ancient covered souq, Aleppo, Syria

Ancient covered souq, Aleppo, Syria

Organisation

Gharipour has pointed out that in spite of the centrality of souqs and bazaars in Middle Eastern history, relatively little is known due to the lack of archaeological evidence.[13] Souqs are traditionally divided into specialized sections dealing in specific types of product, in the case of permanent souqs each usually housed in a few narrow streets and named after the product it specializes in such as the gold souq, the fabric souq, the spice souq, the leather souq, the copy souq (for books), etc. This promotes competition among sellers and helps buyers easily compare prices.

At the same time the whole assembly is collectively called a souq. Some of the prominent examples are Souq Al-Melh in Sana'a, Manama Souq in Bahrain, Bizouriyya Souq in Damascus, Saray Souq in Baghdad, Khan Al-Zeit in Jerusalem, and Zanqat Al-Niswaan in Alexandria.

Though each neighbourhood within the city would have a local Souq selling food and other essentials, the main souq was one of the central structures of a large city, selling durable goods, luxuries and providing services such as money exchange.Workshops where goods for sale are produced (in the case of a merchant selling locally-made products) are typically located away from the souq itself. The souq was a level of municipal administration. The Muhtasib was responsible for supervising business practices and collecting taxes for a given souq while the Arif are the overseers for a specific trade.

Shopping at a souq or market place is part of daily life throughout much of the Middle East.[14] Prices are commonly set by bargaining, also known as haggling, between buyers and sellers.[15]

In literature and art

In the 18th and 19th centuries, as Europeans began to conquer parts of North Africa and the Levant, an interest in Middle Eastern culture and architecture began to flourish. This interest spawned a genre of literary works and paintings that became known as Orientalism.[16] A proliferation of both Oriental fiction and travel writing occurred during the early modern period and many of these works were lavishly illustrated with engravings of every day scenes of Oriental lifestyles, including scenes of market places and market trade.[17] Some of these works were propaganda designed to justify European imperialism in the East, however many artists relied heavily on their everyday experiences for inspiration in their artworks.[18] For example, Charles D'Oyly, who was born in India, published the Antiquities of Dacca featuring a series of 15 engraved plates of Dacca [now Dhaka, Bangladesh] featuring scenes of markets, commerce, buildings and streetscapes.[19] Notable artists in the Orientalist genre include: Jean-Léon Gérôme Delacroix (1824–1904), Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803–1860), Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), Eugène Alexis Girardet 1853-1907 and William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) who all found inspiration in Oriental street scenes, trading and commerce.

_and_Husseinee_Delaun.jpg) The Chouk [souk], engraving from Charles D'Oyly's Antiquities of Dacca , 1814

The Chouk [souk], engraving from Charles D'Oyly's Antiquities of Dacca , 1814 Gossain Katra, Chowk, Patna, by Charles D'Oyley, 1823-1825

Gossain Katra, Chowk, Patna, by Charles D'Oyley, 1823-1825_-_TIMEA.jpg) Carpet Merchant in the Khan el Khaleel, 1878

Carpet Merchant in the Khan el Khaleel, 1878_-_TIMEA.jpg) Shop of a Turkish Merchant in the Soo'ck called Kha'n El-Khalee'lee, 1836

Shop of a Turkish Merchant in the Soo'ck called Kha'n El-Khalee'lee, 1836 Street Market with the Mosque of Sultan Hassan, Egypt, lithograph by Louis Haghe after David Roberts, 1849

Street Market with the Mosque of Sultan Hassan, Egypt, lithograph by Louis Haghe after David Roberts, 1849.jpg) Dans le Souk aux Cuivres [In the Copper Souk] by Nicola Forcella, before 1868

Dans le Souk aux Cuivres [In the Copper Souk] by Nicola Forcella, before 1868 Market Day outside the Walls of Tangiers, Morocco by Louis Comfort Tiffany, 1873

Market Day outside the Walls of Tangiers, Morocco by Louis Comfort Tiffany, 1873 Souk at Konstantynopolu by Stanisław Chlebowski, 19th century

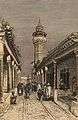

Souk at Konstantynopolu by Stanisław Chlebowski, 19th century Souk at Tunis, wood engraving by T. Taylor, 1886

Souk at Tunis, wood engraving by T. Taylor, 1886 Inside the Souk, Cairo by Charles Wilda, 1892

Inside the Souk, Cairo by Charles Wilda, 1892 The Barber at the Souk by Enrique Simonet, 1897

The Barber at the Souk by Enrique Simonet, 1897 Au Souk [At the Souk], by Eugène Alexis Girardet, late 19th century

Au Souk [At the Souk], by Eugène Alexis Girardet, late 19th century The Fruit Merchant, by Eugène Alexis Girardet, late 19th century

The Fruit Merchant, by Eugène Alexis Girardet, late 19th century Souk des étoffes, Tunis by Anton Robert Leinweber, before 1921

Souk des étoffes, Tunis by Anton Robert Leinweber, before 1921 El Zoco [The Souk] by José Navarro Llorens, 1900

El Zoco [The Souk] by José Navarro Llorens, 1900 Entrance to the Souk at Constantinople, by Simon Agopian, 1905

Entrance to the Souk at Constantinople, by Simon Agopian, 1905_-_TIMEA.jpg) Souk Silah, the Armourers' Bazaar, Cairo, from D.S. Margoliouth, Cairo, Jerusalem, & Damascus: three chief cities of the Egyptian Sultans, 1907

Souk Silah, the Armourers' Bazaar, Cairo, from D.S. Margoliouth, Cairo, Jerusalem, & Damascus: three chief cities of the Egyptian Sultans, 1907%2C_Damascus._(1907)_-_TIMEA.jpg) Souk Hamareh, Damascus by from D.S. Margoliouth, Cairo, Jerusalem, & Damascus: three chief cities of the Egyptian Sultans, 1907

Souk Hamareh, Damascus by from D.S. Margoliouth, Cairo, Jerusalem, & Damascus: three chief cities of the Egyptian Sultans, 1907

Select list of souqs

- Lists

- Individual souqs

- Al Mina Fruit and Vegetable souq Abu Dhabi

- Al-Buzuriyah Souq, Damascus, Syria

- Al-Hamidiyah Souq Syria

- Al Souk Al Kabir Dubai

- Al Souk Al Kabir Dubai

- Grand Socco Tangiers, Morocco

- Houmt El Souk (The Souq neighbourhood) Tunis

- Khan el-Khalili

- Mahane Yehuda Market

- Manama Souq Bahrain

- Petit Socco, also known as "Souk Dakhli", Tangiers, Morocco

- Souk Ahras Algeria

- Souk Ech-Chaouachine Tunisia

- Souk Es Sekajine Tunisia

- Souk Lahad Tunisia

- Souk Jara Jordan

- Souq al-Madina

- Souk al-Tawileh Lebanon

- Souk El Gharb Lebanon

- Souk Okaz Saudi Arabia

- Souq Waqif Qatar

See also

- Arcade: a covered passageway with stores along one or both sides.

- Bazaar: another term for souk or marketplace

- Bazaari: a person who works in a bazaar or souk

- Bedesten (also known as bezistan, bezisten, bedesten) refers to a covered bazaar and an open bazaar in the Balkans.

- Carmel Market

- Gold Souq: a market trading in gold.

- History of marketing

- Marketplace

- Medina quarter

- Retail

References

| Look up souq in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Souqs. |

- ↑ "Aleppo.us: Old souqs of Aleppo (in Arabic)".

- ↑ "Mahane Yehuda website". Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ↑ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, pp 3-15

- ↑ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012 pp 14-15

- ↑ Hanachi, P. and Yadollah, S., "Tabriz Historical Bazaar in the Context of Change," ICOMOS Conference Proceedings, Paris, 2011

- ↑ Moosavi, M. S. Bazaar and its Role in the Development of Iranian Traditional Cities [Working Paper], Tabriz Azad University, Iran, 2006

- ↑ Mehdipour, H.R.N, "Persian Bazaar and Its Impact on Evolution of Historic Urban Cores: The Case of Isfahan," The Macrotheme Review [A multidisciplinary Journal of Global Macro Trends], Vol. 2, no. 5, 2013, p.13

- ↑ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, pp 4-5

- ↑ Nejad, R. M., “Social bazaar and commercial bazaar: comparative study of spatial role of Iranian bazaar in the historical cities in different socio-economical context,” 5th International Space Syntax Symposium Proceedings, Netherlands: Techne Press, D., 2005,

- ↑ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, p. 4

- ↑ "eAleppo: The old Souqs of Aleppo (in Arabic)". Esyria.sy. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "eAleppo:Aleppo city major plans throughout the history" (in Arabic).

- ↑ Gharipour, M., "The Culture and Politics of Commerce," in The Bazaar in the Islamic City: Design, Culture, and History, Mohammad Gharipour (ed.), New York, The American University in Cairo Press, 2012, pp 4-5

- ↑ "Doha's Sprawling Souq Enters the Modern Era, The National [UAE edition}, 25 February, 2011, " https://www.thenational.ae/business/travel-and-tourism/doha-s-sprawling-souq-enters-the-modern-age-1.420872; Ramkumar, E.S., "Eid Shopping Reaches Crescendo," Arab News, 13 October, 2007, http://www.arabnews.com/node/304533

- ↑ Islam, S., "Perfecting the Haggle," The National, [UAE edition], 27 March, 2010, https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/perfecting-the-haggle-why-it-s-always-worth-walking-away-1.546397

- ↑ Nanda, S. and Warms, E.L., Cultural Anthropology, Cengage Learning, 2010, p. 330

- ↑ Houston, C., New Worlds Reflected: Travel and Utopia in the Early Modern Period, Routledge, 2016

- ↑ Meagher, J., "Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art," [The Metropolitan Museum of Art Essay], Online: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/euor/hd_euor.htm

- ↑ D'Oyly, Charles, Antiquities of Dacca, London, J. Landseer, 1814 as cited in Bonham's Fine Books and Manuscripts Catalogue, 2012, https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/20048/lot/2070/

-Jerusalem-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Rock_(SE_exposure).jpg)