Shortages in Venezuela

| Part of Crisis in Bolivarian Venezuela | |

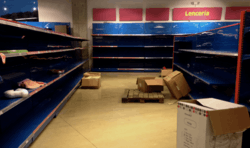

Top to bottom, left to right: A Venezuelan eating from garbage. Empty shelves in a store. Venezuelans in line to enter a store for scarce products. | |

| Date | 2010 – ongoing[1] |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Cause | Government policies, corruption and smuggling[2][3] |

| Outcome | Hunger, disease, civil unrest and refugee crisis. |

| Crisis in Venezuela |

|---|

|

| Effects |

|

|

| Events |

|

|

| Elections |

|

|

| Protests |

| Timeline |

|

|

| Armed violence |

|

|

Shortages in Venezuela of regulated food staples and basic necessities have been widespread following the enactment of price controls and other policies under the government of Hugo Chávez[4][5] and exacerbated by the policy of withholding United States dollars from importers under the government of Nicolás Maduro.[6] The severity of the shortages has led to the largest refugee crisis ever recorded in the Americas.[7][8][9] The Bolivarian government's denial of the crisis[10] and its refusal to accept offers of aid from Amnesty International, the United Nations, and other groups has made conditions even worse.[11][12][12][13] The United Nations and the Organization of American States have stated that the shortages have resulted in unnecessary deaths in Venezuela and urged the government to accept humanitarian aid.[14]

There are shortages of milk, meat, coffee, rice, oil, precooked flour, butter, toilet paper, personal hygiene products and medicines.[4][15][16][17] By January 2017, the shortage of medicines reached 85%, according to the Pharmaceutical Federation of Venezuela (Federación Farmacéutica de Venezuela).[18] Hours-long lines have become common, and those who wait in them are sometimes disappointed. Some Venezuelans have resorted to eating wild fruit and garbage.[19][20][21][22]

On 9 February, 2018 a group of Special Procedures and the Special Rapporteurs on food, health, adequate housing and extreme poverty issued a joint statement on Venezuela that partly read, “Vast numbers of Venezuelans are starving, deprived of essential medicines, and trying to survive in a situation that is spiraling downwards with no end in sight”.[23]

History

Chávez administration

Since the 1990s, food production in Venezuela has dropped continuously, with Hugo Chávez's Bolivarian government beginning to rely upon imported food using the country's then-large oil profits.[26]

In 2003, the government created CADIVI (now CENCOEX), a currency control board charged with handling foreign exchange procedures to control capital flight by placing currency limits on individuals.[27][28] Such currency controls have been determined to be the cause of shortages according to many economists and other experts.[29][30][31] However, the Venezuelan government blamed other entities such as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and smugglers for shortages, and has stated that an "economic war" had been declared on Venezuela.[29][30][31][32][33][34][35]

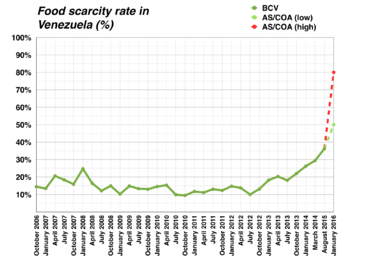

During the presidency of Chávez, Venezuela faced occasional shortages owing to high inflation and government financial inefficiencies.[36] In 2005, Chávez announced the initiation of Venezuela's own "great leap forward", following the example of Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward.[37] An increase in shortages began to occur that year as 5% of items became unavailable according to the Central Bank of Venezuela.[38] In January 2008, 24.7% of goods were reported to be unavailable in Venezuela, with the scarcity of goods remaining high until May 2008, when there was a shortage of 16.3% of goods.[39] However, shortages increased again in January 2012 to nearly the same rate as in 2008.[39]

Maduro administration

|

|

Following Chávez's death and the election of his successor Nicolás Maduro in 2013, shortage rates continued to increase and reached a record high of 28% in February 2014.[40] Venezuela stopped reporting its shortage data after the rate stood at 28%.[41] In January 2015, the hashtag "AnaquelesVaciosEnVenezuela" or "EmptyShelvesInVenezuela" was the number one trending topic on Twitter in Venezuela for two days, with Venezuelans posting pictures of empty store shelves around the country.[42][43]

In August 2015, American private intelligence agency company Stratfor used two satellite images of Puerto Cabello, Venezuela's main port used for importing goods, to show how severe shortages had become in Venezuela. One image from February 2012 showed the ports full of shipping containers when the Venezuelan government's spending was near a historic high before the 2012 Venezuela presidential election. A second image from June 2015 shows the port with many fewer containers, since the Venezuelan government could no longer afford to import goods, as oil revenues dropped.[36] At the end of 2015, it was estimated there was a shortage of over 75% of goods in Venezuela.[44]

By May 2016, experts feared that Venezuela was possibly entering a period of famine, with President Maduro encouraging Venezuelans to cultivate their own food.[26] In January 2016, it was estimated, that the food scarcity rate (indicador de escasez)[25] was between 50% and 80%.[26] The newly elected National Assembly, composed primarily of opposition delegates, "declared a national food crisis" a month later in February 2016.[26] Many Venezuelans then began to suffer from shortages of common utilities, such as electricity and water, because of the prolonged period of mishandling and corruption under the Maduro government.[45][46][47] By July 2016, Venezuelans desperate for food moved to the Colombian border. Over 500 women stormed past Venezuelan National Guard troops into Colombia looking for food on 6 July 2016.[48] By 10 July 2016, Venezuela temporarily opened its borders, which had been closed since August 2015, for 12 hours. Over 35,000 Venezuelans traveled to Colombia for food within that period.[49] Between 16–17 July, over 123,000 Venezuelans crossed into Colombia seeking food. The Colombian government set up what it called a "humanitarian corridor" to welcome Venezuelans.[49] Around the same time in July 2016, reports of desperate Venezuelans rummaging through garbage for food appeared.[20][21]

By early 2017, priests began telling Venezuelans to label their garbage so needy individuals could feed on their refuse.[50] In March 2017, despite having the largest oil reserves in the world, some regions of Venezuela began having shortages of gasoline with reports that fuel imports had begun.[51] The government continued to deny there was a "humanitarian crisis", instead saying there was simply "a decrease in the availability of food". Yván Gil, vice minister of relations to the European Union, said that an "economic war" had affected "the availability of food, but [Venezuela is] still within the thresholds set by the UN".[52] Following targeted sanctions by the United States government in late-2017 due to the controversial 2017 Constituent National Assembly, the Maduro government began to blame the United States for shortages. It enacted "Plan Rabbit", encouraging Venezuelans to breed rabbits, slaughter them and eat their meat.[53]

By early 2018, gasoline shortages began to spread, with hundreds of drivers in some regions waiting in lines to fill their tanks, sleeping overnight in their vehicles during the process.[54][55][56] In a September 2018 Meganalisis survery, nearly one-third of Venezuelans stated they consumed only one meal per day while 78.6 percent of respondents said they had issues with food security.[57]

Causes

Government policies

Overspending and import reliance

President Hugo Chávez' policies relied heavily on oil revenues to fund large quantities of imports. Production under Chávez dropped because of his price control policies and "poorly managed" expropriations. His successor, Nicolás Maduro, continued most of Chávez' policies until they became unsustainable. When oil profits began declining in 2014, Maduro began limiting imports needed by Venezuelans and shortages began to grow. Chávez left Maduro with a high debt because of his overspending. Foreign reserves, usually saved for economic distress, were being spent to service debt and to avoid default, instead of being used to purchase imported goods. Domestic production, which had already been damaged by government policies, was unable to replace the necessary imported goods.[59]

According to economist Ángel Alayón, "the Venezuelan government has direct control over food distribution in Venezuela" and the movement of all food, even among private companies, is controlled by the government.[60] Alayón states the problem is not distribution, however, but production since "nobody can distribute what is not produced".[60] Expropriations by the government resulted in a drop in production in Venezuela.[60][61][62] According to Miguel Angel Santos, a researcher at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, as a result of expropriations of private means of production since 2004, "production was destroyed", while a "wave of consumption based on imports" occurred when Venezuela had abundant oil money.[63] With poor production and a dependence on imports, the drop of oil prices beginning in 2014 made it impossible for the government to import necessary goods for Venezuelans.[2]

Currency and price controls

_on_a_logarithmic_scale.png)

In the first few years Chavez was in office, his newly created social programs required large amounts of funding to make the desired changes.[27] On 5 February 2003, the government created CADIVI, a currency control board charged with handling foreign exchange transactions.[27] It was created to control the flight of capital from the country by placing limits on the amount of foreign currency individuals could purchase.[27] The Chávez administration also enacted agricultural measures that caused food imports to rise dramatically. This slowed domestic production of such agricultural mainstays as beef, rice, and milk.[64] With Venezuela's reliance on imports and its lack of US dollars to pay for them, shortages resulted.[65]

With limits on foreign currency, a currency black market developed since Venezuelan merchants relied on the import of goods that required payments with reliable foreign currencies.[66] As Venezuela printed more money for their social programs, the bolívar continued to devalue for Venezuelan citizens and merchants since the government held most of the more reliable currencies.[66] Because merchants could purchase only limited amounts of necessary foreign currency from the Venezuelan government, they resorted to the black market. This in turn raised the merchant's costs which resulted in price increases for consumers.[67] The high black market rates made it difficult for businesses to purchase necessary goods or earn profits since the government often forced them to make price cuts. Maduro’s government increased price controls after inflation grew and shortages of basic goods worsened. He called the policy an "economic counterattack" against the "parasitic bourgeoisie". Price regulators, with military backing, forced businesses to lower prices on everything from electronics to toys. One example is Venezuelan McDonald's franchises began offering a Big Mac meal for 69 bolivars or $10.90 in January 2014, though only making $1 at the black market rate.[68] Since businesses made lower profits, this led to further shortages because they could not afford to pay to import or produce the goods that Venezuela relies on.[69][60]

With the short supply of foreign currencies and Venezuela's reliance on imports, debt is created. Without settling its outstanding debt, Venezuela could not import the materials necessary for domestic production. Without such imports, more shortages were created since there was an increasing lack of production as well.[60]

Corruption

Following mass looting in June 2016 due to shortages which resulted in the deaths of at least three, on 12 July 2016, President Maduro granted Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López the power to oversee product transportation, price controls, and the Bolivarian missions. He also had his military oversee five of Venezuela's main ports.[70][71][72] Maduro's actions made General Padrino one of the most powerful people in Venezuela, possibly "the second most powerful man in Venezuelan politics".[71][73]

Ret. General Cliver Alcala[2]

An Associated Press investigation published in December 2016 found that "instead of fighting hunger, the military is making money from it". Military sellers would drastically increase the cost of goods and create shortages by hoarding products. Ships containing imports would often be held at bay until military officials at Venezuela's ports were paid off. Officials bypassed standard practices, such as performing health inspections, pocketing money normally spent on such certificates. One anonymous businessman who participated in the lucrative food dealings with Venezuelan military officials, and had contracts valued at $131 million between 2012 and 2015, showed the Associated Press his accounts for his business in Venezuela. The government would contract him for more than double the actual cost for products. For example, one corn contract of $52 million would be $20 million more than the market average. Then the businessman would have to use the extra money to pay military personnel to import such products. The businessman said he had been paying millions of dollars to military officials for years, and that the food minister, Gen. Rodolfo Marco Torres, once had to be paid $8 million just to import goods into Venezuela.[2] Documents seen by the Associated Press showing prices for corn also revealed that the government budgeted $118 million in July 2016, an overpayment of $50 million over average market prices for that month.[2]

According to retired Gen. Antonio Rivero, Maduro "gave absolute control to the military", which "drained the feeling of rebellion from the armed forces, and allowed them to feed their families". The military has also used currency control licenses to obtain dollars at a lower exchange rate than the average Venezuelan. The military shared the licenses with friendly businessmen to import very few goods with the cheaper dollars while pocketing the remaining dollars. Documents show that Gen. Rodolfo Marco Torres had given contracts to potential shell companies. Two companies, the Panamanian located Atlas Systems and J.A. Comercio de Generous Alimenticios diverted $5.5 million to Swiss accounts of two brothers-in-law of then-food minister, General Carlos Osorio in 2012 and 2013.[2]

In late January 2017, members of the United States Congress responded to the Associated Press investigation, suggested making targeted sanctions against corrupt Venezuelan officials who had taken advantage of the food shortages and participated in graft. Democratic Senator of Maryland and ranking member of the Foreign Relations Committee Ben Cardin stated, "When the military is profiting off of food distribution while the Venezuelan people increasingly starve, corruption has reached a new level of depravity that cannot go unnoticed." Senator Marco Rubio said that, "This should be one of President Trump's first actions in office."[74]

Explanations by the government

Smuggling

In an interview with President Maduro by The Guardian, it was noted that a "significant proportion" of the subsidized basic goods in short supply were being smuggled into Colombia and sold for far higher prices.[3] The Venezuelan government claimed that as much as 40% of the basic commodities it subsidizes for the domestic market were being disposed of in this manner.[32] However, economists disagreed with the Venezuelan government's claim saying that only 10% of subsidized products are smuggled out of the country.[75] Reuters noted that the creation of currency controls and subsidies were the main factors contributing to smuggling.[76]

Following President Maduro's move to grant the military control of Venezuela's food infrastructure, military personnel have sold contraband into Colombia. One member, 1st Lt. Luis Alberto Quero Silva of the Venezuelan National Guard, was arrested for possessing three tons of flour, which was likely part of a more elaborate graft operation among the country's military.[77]

Food consumption

In 2013, the president of the Venezuelan government's Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) Elias Eljuri, referring to a national survey, suggested that all shortages in the country were due to Venezuelans' eating, saying that "95% of people eat three or more meals a day".[78][79][80] Data provided by the Venezuelan government's statistical office instead showed that in 2013, food consumption by Venezuelans actually decreased.[81] By March 2016, 87% of Venezuelans were reportedly consuming less due to the shortages they faced.[26] As of 2016, the average Venezuelan living in extreme poverty lost nearly 19 pounds due to lack of food.[82] In March 2017, a basket of basic grocery items cost four times the monthly minimum wage and by April, more than 11% of the children in the country suffered from malnutrition.[82][83] By 2018, more than 30 percent of Venezuelans were only eating one meal per day.[57]

Response

Censorship and denial

The Venezuelan government often censored and denied health information and statistics surrounding the crisis. Doctors received threats not to release malnutrition data. In one case in "the Ministry of Health’s 2015 annual report, the mortality rate for children under 4 weeks old had increased a hundredfold, from 0.02 percent in 2012 to just over 2 percent". The government responded to the release of this information on the Ministry's website saying had been hacked. The information was taken down from the Internet, the health minister was fired, and the military was put in charge of Venezuela's health ministry.[84]

President Maduro said he recognized there is hunger in Venezuela, though he blamed it on an economic war.[84] Yván Gil, Venezuela's vice minister of relations to the European Union, denied a "humanitarian crisis". Instead he stated there was simply "a decrease in the availability of food", saying an "economic war" had affected "the availability of food, but we are still within the thresholds set by the UN".[52] In an Al Jazeera interview with president of the Constituent Assembly Delcy Rodríguez, she stated, "I have denied and continue denying that Venezuela has a humanitarian crisis". As a result, international intervention in Venezuela would not be justified. She also described statements by Venezuelans calling for international assistance as "treasonous".[85]

Rationing

Food

Economists state the Venezuelan government began rationing in 2014 for several reasons including an unproductive domestic industry that had been negatively affected by nationalization and government intervention, and confusing currency controls that made it unable to provide the dollars importers needed to pay for all the of basic products that enter Venezuela.[75] According to Venezuelan residents, the government also rationed public water to those who used water over 108 hours a week because of the nation's poor water delivery systems.[75] Gasoline was also rationed allegedly because subsidized Venezuelan gasoline was being smuggled to Colombia where it was sold for a higher price.[75]

In February 2014, the government said it had confiscated more than 3,500 tons of contraband food ad fuel at the border with Colombia, which it said was intended for "smuggling" or "speculation". The president of the National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello, said the confiscated food should be given to the Venezuelan people and should not be "in the hands of these gangsters."[86] One month later, President Maduro introduced a "biometric card" called Tarjeta de Abastecimiento Seguro, that required the user's fingerprint for purchases in state-run supermarkets or participating businesses. The device was allegedly meant to combat smuggling and price speculation.[87][88] It has been described as being both like a loyalty program and a ration card.[89][90][91] In May 2014, months after the card was introduced, it was reported that 503,000 Venezuelans had registered for it.[92] In August 2014, it was reported that the Tarjeta de Abastecimiento Seguro failed to move past the trial phase, and that another "biometric card" was going to be developed according to President Maduro.[93]

Soon after, in August 2014, President Maduro announced the creation of a new voluntary fingerprint scanning system that was allegedly aimed at combating food shortages and smuggling.[94][95] The Venezuelan government announced that 17,000 troops would be deployed along its border with Colombia.[96] They were to assist in closing down traffic each night to strengthen anti-smuggling efforts.[97][98] The effect of the nightly closings was to be assessed after 30 days.[32] Following large shortages in January 2015, Makro announced that some stores would begin using fingerprint systems and that customers would be rationed both daily and monthly.[99]

Utilities

Michael Shifter, president of Inter-American Dialogue[47]

Rationing of electricity and water began to increase into 2016. Water shortages in Venezuela resulted in the government mandating the rationing of water. Many Venezuelans no longer had access to water piped to their homes and instead relied on the government to provide water a few times monthly. Desperate Venezuelans often displayed their frustrations through protests and began to steal water "from swimming pools, public buildings, and even tanker trucks" to survive.[100] Due to the water shortages, there were "increased [numbers of] cases of diseases such as scabies, malaria, diarrhea and amoebiasis in the country", according to Miguel Viscuña, Director of Epidemiology of the Health Corporation of Central Miranda[101]

Venezuela also experienced shortages of electricity and was plagued by common blackouts. On 6 April 2016, President Maduro ordered public workers not to go to work believing it would cut down on energy consumption.[47] However, the workers actually used more energy in their homes using air conditioning, electronics and appliances.[102] On 20 April 2016, the government ordered the rationing of electricity in ten Venezuelan states, including the capital city of Caracas; This followed after other attempts to curb electricity usage including moving Venezuela's time zone ahead and telling Venezuelan women to stop using hairdryers had failed.[103] Two days later, on 22 April 2016, the minister of electricity, Luis Motta Dominguez, announced that beginning the following week, forced blackouts would occur throughout Venezuela four hours per day for the next 40 days.[47]

Reaction to rationing

Venezuelan consumers had mainly negative feelings toward the fingerprint rationing system, saying it created longer lines, especially when fingerprint machines malfunctioned. They felt the system did nothing to relieve shortages because the large economic changes the country needed to make were simply overlooked.[75] Following the announcement of the fingerprint system, protests broke out denouncing the proposed move in many cities in Venezuela.[104][105][106][107] The MUD opposition coalition called on Venezuelans to reject the new fingerprinting system and called on supporters to hold a nationwide cacerolazo (a noisy form of protest).[108][109] These were primarily held in areas that traditionally opposed the government.[107] Students in Zulia state also demonstrated against the proposed system.[110] Lorenzo Mendoza, the president of Empresas Polar, Venezuela's largest food producer, expressed his disagreement with the proposed system, saying it would penalize 28 million Venezuelans for the smuggling carried out by just a few.[111] Days after the announcement, the Venezuelan government scaled back its plans for implementing the new system, saying it was now voluntary and is only for 23 basic goods.[112]

Despite public displeasure with the system, in an October 2014 Wall Street Journal article, it was reported that the fingerprint rationing system had expanded to more state-owned markets.[75]

Local Supply and Production Committee (CLAP)

According to then-Vice President of Venezuela, Aristóbulo Istúriz, the government-operated Local Supply and Production Committees (CLAP) that provides food to Venezuelans in need, are a "political instrument to defend the revolution". Allegations arose that only supporters of Maduro and the government were provided food, while critics were denied access to goods. PROVEA, a Venezuelan human rights group, described CLAPs as "a form of food discrimination that is exacerbating social unrest".[113]

Luisa Ortega Díaz, Chief Prosecutor of Venezuela from 2007 to 2017 revealed that President Maduro had profited from the food crisis. CLAP made contracts with Group Grand Limited, a Mexican entity owned by Maduro through frontmen Rodolfo Reyes, Álvaro Uguedo Vargas and Alex Saab. Group Grand Limited would sell foodstuffs to CLAP and receive government funds.[114][115][116]

On 19 April 2018, after a multilateral meeting between over a dozen European and Latin American countries, United States Department of the Treasury officials stated that they had collaborated with Colombian officials to investigate corrupt import programs of the Maduro administration including CLAP. They explained that Venezuelan officials pocketed 70% of the proceeds allocated for importation programs destined to alleviate hunger in Venezuela. Treasury officials said they sought to seize the proceeds that were being funneled into the accounts of corrupt Venezuelan officials and hold them for a possible future government in Venezuela.[117][118] A month later, on 17 May 2018, the Colombian government seized 25,200 CLAP boxes containing about 400 tons of decomposing food, which was destined for distribution to the Venezuelan public.[119] The Colombian government said they were investigating shell companies and money laundering related to CLAP operations, and claimed the shipment was to be used to buy votes during the 2018 Venezuelan presidential election.[119]

Effects

Arbitrage and hoarding

As a result of the shortages and price controls, arbitrage (or bachaqueo), the ability to buy low and sell high, came about in Venezuela.[60] For example, goods subsidized by the Venezuelan government were smuggled out of the country and sold for a profit.[3] Hoarding also increased as Venezuelan consumers grew nervous over shortages.[60]

Crime

Individuals have resorted to violent theft to acquire items that shortages have made difficult to obtain. Venezuelan motorcycle organizations have reported that their members have been murdered for their motorcycles due to the shortage of motorcycles and spare parts. There have also been reports of Venezuelan authorities being killed for their weapons, and trucks full of goods being attacked to steal desirable merchandise they are carrying.[120]

Hunger

The government originally took pride in its reduction of malnutrition when it had oil revenues to fund its social spending in the 2000s.[121] However, by 2016, the majority of Venezuelans were eating less[26][122] and spending the majority of their wages on food.[123] A 2016 survey by the Bengoa Foundation found nearly 30% of children malnourished. According to nutritionist Héctor Cruces, generations of Venezuelans will be affected by the shortages becoming malnourished, causing stunted growth and obesity.[124] Venezuelans' immune systems were also weakened due to the lack of food intake, while the lack of water also caused hygienic issues.[125]

The New York Times, 2017

The New York Times stated in a 2016 article "Venezuelans Ransack Stores as Hunger Grips the Nation" that "Venezuela is convulsing from hunger ... The nation is anxiously searching for ways to feed itself".[126] The hunger Venezuelans often experienced resulted in growing discontent that culminated with protests and looting.[123][126]

A 2017 report by The New York Times explained how hunger had begun to become so extreme in the country that hundreds of children began to die throughout Venezuela. That year, cases of malnutrition rose sharply as years of economic mismanagement began to grow deadlier. Nearly every hospital in Venezuela stated they did not have enough baby formula, while 63% said they had no baby formula at all.[84] Dozens of deaths have also been reported the result of Venezuelans resorting to eating harmful and poisonous substances, such as bitter yuca, in order to curb starvation.[127][128]

"The Maduro Diet"

While suffering from lack of food due to the shortages under President Nicolás Maduro, Venezuelans called their weight loss from malnourishment and hunger the "Maduro Diet".[121] The "diet" was described as "a collective and forced diet",[129] with many Venezuelans resorting to extreme measures to feed themselves, including eating garbage[20][21] and wild fruits,[22] and selling personal possessions for money to buy food.[130] By the end of 2016, more than three-quarters of Venezuelans had lost weight because of their inadequate food intake,[131] with about the same proportion of people saying they had lost 8.5 kg (19 lb) from a lack of food in 2016 alone.[132] In 2017, studies found that 64% of Venezuelans saw a reduction in weight, with 61% saying they go to sleep hungry, while the average Venezuelan lost 12 kg (26 lb).[133]

In public, President Maduro often avoids or rebukes issues brought to him by Venezuelans regarding their diets.[135] Many Venezuelans have criticized his response to the nation's hunger on state television.[135] During one state address in early 2017, President Maduro joked about how one member of his staff had begun looking skinny, with the member saying "I’ve lost about 44 pounds since December" due to the "Maduro diet".[134] Maduro replied, saying the "Maduro diet" worked as an aphrodisiac.[134]

Medicine

Medical shortages in the country hampered the medical treatment of Venezuelans.[136] Shortages of antiretroviral medicines to treat HIV/AIDS affected about 50,000 Venezuelans, potentially causing thousands them with HIV to develop AIDS.[137] Venezuelans also said it was hard to find acetaminophen to help alleviate the newly introduced chikungunya virus, a potentially lethal mosquito-borne disease.[138] Diphtheria, which had been eradicated from Venezuela in the 1990s, reappeared in 2016 due to shortages of basic drugs and vaccines.[125]

Protests

Demonstrations against the effects of shortages have occurred throughout Venezuela. In August 2014, many Venezuelans protested against the fingerprint rationing put in place by the government[106] while protests against shortages grew from late-2014 into 2015.[139] Of the 2,836 protests that occurred in the first half of 2015, a little more than one in six events were demonstrations against shortages.[140] In 2016 after shortages of water began to occur, there were growing incidents of protest as a result.[100]

Looting

In 2015, growing frustration with shortages and having to wait for hours in long lines for products, led to looting throughout Venezuela.[141] According to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict, hundreds of events involving looting and attempted looting occurred throughout the country in the first half of the year.[141][140] It was also noted that looting was not new to the country, but had been increasing throughout 2015. Looters showed signs of "desperation and discomfort" and resorted to looting because they were "frustrated" by the inability to find basic goods.[140]

In July 2015, BBC News said that due to the common shortages in Venezuela, every week there were videos being shared online showing Venezuelans looting supermarkets and trucks for food.[142] In Ciudad, Guyana at the end of July, looting occurred in the city that resulted in one death and the arrest of dozens.[143]

Psychological

In 2015, concerns about shortages and inflation overtook violent crime as Venezuelans' main worry for the first time in years according to pollster Datanalisis. According to the chief executive of Datanalisis, Luis Vicente Leon, since insecurity had plagued Venezuela for years, Venezuelans had become accustomed to crime and gave up hope for a solution to it. Vicente Leon said that Venezuelans had greater concerns over shortages and became preoccupied with the difficulties surrounding them instead. Eldar Shafir, author and American behavioral scientist, said that the psychological "obsession" with finding scarce goods in Venezuela is because the rarity of the item makes it "precious".[144]

Despite the threat of violent protests occurring throughout Venezuela, children were more affected psychologically by the economic crisis than violence. Abel Saraiba, a psychologist with children's rights organization Cecodap said in 2017, "We have children from a very early age who are having to think about how to survive", with half of her young clients requiring treatment because of the crisis. Children are often forced to stand in food lines or beg with their parents, while the games they play with other children revolve around finding food.[145] In more extreme cases, Friends of the Child Foundation Amerita Protección (Fundana) psychologist Ninoska Zambrano explains that children are offering sexual services to obtain food. Zambrano said "Families are doing things that not only lead them to break physically, but in general, socially, we are being morally broken".[146]

Society

Due to the shortages and the associated hunger, many women began to be sterilized to avoid childbirth since they could not provide enough food for their families. Young men joined gangs to fight for food, often showing signs of injury following violent confrontations for morsels of meals. Families gathered at dumpsters in the evening to obtain goods. Children would attempt to take on jobs themselves to earn money for food or even run away so they could try to find sustenance on their own.[84]

Statistics

There was an 80-90% shortage rate of milk (powdered and liquid), margarine, butter, sugar, beef, chicken, pasta, cheese, corn flour, wheat flour, oil, rice, coffee, toilet paper, diapers, laundry detergent, bar soap, bleach, dish, shampoo and soap toilet in February 2015.[147]

In March 2016, it was estimated that 87% of Venezuelans were consuming less due to the shortages. There was a 50% to 80% rate of food shortages, and 80% of medicines were in short supply or unavailable.[26] By December 2016, 78.4% of Venezuelans had lost weight due to lack of food.[131]

By February 2017, the Venezuela's Living Conditions Survey, managed by a multi-university organization in Venezuela, reported that about 75% of Venezuelans had lost weight in 2016. The survey had also stated that 82.8% of Venezuelans were living in poverty, 93% could no longer afford food and that one million Venezuelan school children did not attend classes "due to hunger and a lack of public services".[132]

International aid

Amnesty International, the United Nations and other groups have offered aid to Venezuela. The Venezuelan government has declined such assistance, however,[11] with Delcy Rodriguez denying "Venezuela has a humanitarian crisis."[148]

Venezuelans in other countries often organize benefits for those living in Venezuela, collecting products and shipping them to those they trust there. Experts say that due to the extreme state of shortages, it is necessary for many international family members to send essentials to their families.[149]

List of items affected

Listed below and categorized alphabetically are common items that have been or are currently affected by shortages in Venezuela:

Food products

B

C

E

F

H

I

J

L

M

O

P

R

S

V

W

Health and hygiene products

A

B

- Birth Control Pills[177]

- Blood[173]

- Blood reagents[173]

- Breast implants[178]

C

D

E

G

H

I

L

M

P

R

S

T

U

Household and maintenance products

A

B

C

D

F

I

N

T

V

Miscellaneous products

B

C

G

N

S

V

See also

References

- ↑ McElroy, Damien (23 June 2010). "Chavez pushes Venezuela into food war". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dreier, Hannah; Goodman, Joshua (28 December 2016). "Venezuela military trafficking food as country goes hungry". Associated Press. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 Milne, Seumas; Watts, Jonathan. "Venezuela protests are sign that US wants our oil, says Nicolás Maduro". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Venezuela's currency: The not-so-strong bolívar". The Economist. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ "Venezuela's black market rate for US dollars just jumped by almost 40%". Quartz. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Dulaney, Chelsey; Vyas, Kejal (16 September 2014). "S&P Downgrades Venezuela on Worsening Economy Rising Inflation, Economic Pressures Prompt Rating Cut". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ Board, Editorial (23 February 2018). "Opinion | Latin-America's worst-ever refugee crisis: Venezuelans". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

This human outflow, ... is the largest displacement of people in Latin American history

- ↑ Hylton, Wil S. (9 March 2018). "Leopoldo López Speaks Out, and Venezuela's Government Cracks Down". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

Venezuela is the most urgent humanitarian disaster in the Western Hemisphere, producing the largest exodus of refugees in the history of the Americas

- ↑ "Venezuela's mounting refugee crisis". Financial Times. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ↑ "Maduro niega la diáspora venezolana en la ONU: Se ha fabricado por distintas vías una crisis migratoria - LaPatilla.com". LaPatilla.com (in Spanish). 2018-09-26. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- 1 2 Charner, Flora (14 October 2016). "The face of hunger in Venezuela". CNN. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- 1 2 Vyas, Kejal; Dube, Ryan (6 April 2018). "Venezuelans Die as Maduro Government Refuses Medical Aid". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ Glüsing, Jens (8 August 2018). "The Country of Hunger: A State of Deep Suffering in Venezuela's Hospitals". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "ONU y OEA denuncian muertes por escasez de medicamentos, falta de higiene y deterioro de hospitales en Venezuela - LaPatilla.com". LaPatilla.com (in Spanish). 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ↑ "La escasez también frena tratamientos contra cáncer". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela sufre escasez de prótesis mamarias". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Why are Venezuelans posting pictures of empty shelves?". BBC. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Caraballo-Arias, Yohama; Madrid, Jesús; Barrios, Marcial (2018-09-25). "Working in Venezuela: How the Crisis has Affected the Labor Conditions". Annals of Global Health. 84 (3). doi:10.29024/aogh.2325. ISSN 2214-9996.

- ↑ Cawthorne, Andrew (21 January 2015). "In shortages-hit Venezuela, lining up becomes a profession". Reuters. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 MacDonald, Elizabeth (26 May 2016). "Exclusive: Harrowing Video Shows Starving Venezuelans Eating Garbage, Looting". Fox Business. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Sanchez, Fabiola (8 June 2016). "As hunger mounts, Venezuelans turn to trash for food". Associated Press. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- 1 2 "Mangoes fill the gaps in Venezuela's food crisis". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Venezuela: Dire living conditions worsening by the day, UN human rights experts warn

- ↑ "EL ASCENSO DE LA ESCASEZ". eluniversal.com. 13 February 2014. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- 1 2 https://web.archive.org/web/20151116200346/http://www.bcv.org.ve/Upload/Publicaciones/bcvozecon042010.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sonneland, Holly K. "Update: Venezuela Is Running Short of Everything". Americas Society/Council of the Americas. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 CADIVI, CADIVI, una medidia necesaria Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Venezuelan Currency Controls and Risks for U.S. Businesses" (PDF). U.S. Embassy Caracas. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- 1 2 Lopez, Virginia (26 September 2013). "Venezuela food shortages: 'No one can explain why a rich country has no food'". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- 1 2 Boyd, Sebastian (7 September 2014). "Venezuelan Default Suggested by Harvard Economist". Bloomberg. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- 1 2 Sequera, Vivan; Toothaker, Cristopher (17 March 2013). "Venezuela Food Shortages Reveal Potential Problems During Chavez Absence". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Venezuela seals border with Colombia to fight smuggling". Yahoo News. AFP. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela sends in troops to force electronics chain to charge 'fair' prices". NBC News. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ "Decree powers widen Venezuelan president's economic war". CNN. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ Yapur, Nicolle (24 April 2014). "Primera ofensiva económica trajo más inflación y escasez". El Nacional (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Bringing Venezuela's Economic Crisis Into Focus". Stratfor. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ Guevara, Aleida (2005). An Interview with Hugo Chavez: Venezuela and the New Latin America (1. ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Ocean. p. 57. ISBN 9781920888008.

This year will be crucial in socioeconomic terms. We have announced the revolution within the revolution: the socioeconomic consolidation ... Mao Tse-tung once said this back in the 1960s, during the Great Leap Forward and that is what I have said to the Venezuelan people ... This year has to be the Great Year Forward for us ...

- ↑ Toscano, Luis (12 September 2014). "2015 en el horizonte" (in Spanish). Quinto Dia. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- 1 2 "Shortage at its highest since May 2008". El Universal. 6 January 2012. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Meza, Alfredo (12 February 2014). "Venezuela alcanza la inflación más alta del mundo" (in Spanish). Spain: El Pais. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Zea, Sendai. "Venezuelan Central Bank Admits Sky-High Inflation". PanAm Post. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ "Usuarios de Twitter vuelven tendencia la etiqueta #AnaquelesVacíosEnVenezuela". El Nacional (in Spanish). 4 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Así rechazan los venezolanos la escasez #AnaquelesVaciosEnVenezuela (Fotos)". La Patilla (in Spanish). 3 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Lozano, Daniel (8 January 2015). "Ni un paso atrás: Maduro insiste con su receta económica". La Nación. Argentina. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ↑ "In Venezuela, An Electricity Crisis Adds To Country's Woes". NPR. 29 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Soto, Noris (18 April 2016). "Yellow water, dirty air, power outages: Venezuela hits a new low". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Romo, Rafael; Gillespie, Patrick (22 April 2016). "40 days of blackouts hit Venezuela amid economic crisis". CNN Money. CNN. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ↑ "Venezuelan women push past border controls for food". BBC News. 6 July 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- 1 2 Woody, Christopher (18 July 2016). "'It's humiliating': Inside the trek thousands of Venezuelans are making just to get food". Business Insider. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ Gramer, Robbie (3 March 2017). "Dire Measures to Combat Hunger in Venezuela". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- 1 2 Suarez, Roberth (22 March 2017). "FOTOS: Escasez de gasolina se agudiza en Barquisimeto". El Impulso (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Viceministro chavista dice en Bruselas que no hay emergencia humanitaria sino falta de comida". La Patilla (in Spanish). 29 May 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ Gillespie, Patrick (14 September 2017). "Can rabbit meat save Venezuela from going hungry?". CNNMoney. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "Cientos de conductores durmieron en sus carros para echar gasolina en Táchira". La Patilla (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- ↑ yojeda@laverdad.com, Yasmín Ojeda / Maracaibo /. "Escasez de gasolina tocará nivel histórico en 2018". Diario La Verdad. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ C.A, GLOBAL HOST. "El Tiempo | Venezuela | Escasez de gasolina se agudiza y proyectan que tendrá que importarse | El Periódico del Pueblo Oriental". eltiempo.com.ve (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- 1 2 "El 30.5% de los venezolanos sólo come una vez al día, según encuesta". La Patilla (in Spanish). 2018-09-18. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- ↑ Bergen, Franz von (3 June 2016). "Exclusive: Supermarkets descend into chaos as Venezuela crisis deepens". Fox News. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ Benzaquen, Mercy (16 July 2017). "How Food in Venezuela Went From Subsidized to Scarce". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Alayón, Ángel (13 May 2015). "Estatizar a Polar es profundizar la escasez". Prodavinci. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ Minaya, Ezequiel; Schaefer Muñoz, Sara (9 February 2015). "Venezuela Confronts Retail Sector". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ "Empty shelves and rhetoric". The Economist. 24 January 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ Mizrahi, Darío (22 March 2015). "Políticas que llevan a un país a la escasez en lugar de la abundancia". Infobae. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ In Venezuela, Land 'Rescue' Hopes Unmet, Washington Post, 20 June 2009

- ↑ Tayler, Jeffrey (10 June 2015). "Venezuela's Last Hope". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- 1 2 Hanke, Steve. "The World's Troubled Currencies". The Market Oracle. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Gupta, Girish (24 January 2014). "The 'Cheapest' Country in the World". TIME. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Pons, Corina (14 January 2014). "McDonald's Agrees to Cut the Price of a Venezuelan Big Mac Combo". Bloomberg. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Goodman, Joshua (22 January 2014). "Venezuela overhauls foreign exchange system". Bloomberg. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Military Seizes Major Ports as Economic Crisis Deepens". Voice of America. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 Martín, Sabrina (13 July 2016). "Venezuela: Maduro Hands over Power to Defense Minister". PanAm Post. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Camacho, Carlos (12 July 2016). "Defense Minister Becomes 2nd Most Powerful Man in Venezuela". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "Venezuela Gets a New Comandante". Bloomberg News. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "US Lawmakers Call for Action on Venezuela Food Corruption". NBC News. 23 January 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schaefer Muñoz, Sara (22 October 2014). "Despite Riches, Venezuela Starts Food Rationing; Government Rolls Out Fingerprint Scanners to Limit Purchases of Basic Goods; 'How Is it Possible We've Gotten to This Extreme'". Dow Jones & Company Inc. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuelans turn to fish smuggling to survive economic crisis". Reuters. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Clavel, Tristan. "In Food-Starved Venezuela, Cartel of the Flour?". InsightCrime. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ↑ "Eljuri: 95% de los venezolanos comen tres y cuatro veces al día". Agencia Venezolana de Noticias. 22 May 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ↑ "Toilet paper shortage is because 'Venezuelans are eating more' argues the government". MercoPress. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ A. Ferdman, Roberto (24 May 2013). "Venezuela's grand plan to fix its toilet-paper shortage: $79 million and a warning to stop eating so much". Quartz. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ "La crisis de la economía chavista provoca que los venezolanos coman vez menos". Infobae. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Venezuelans are losing weight amid food shortages, skyrocketing prices". money.cnn.com. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ "Venezuela's hunger crisis is for real". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Kohut, Meredith (17 December 2017). "As Venezuela Collapses, Children Are Dying of Hunger". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ "Delcy Rodriguez: No humanitarian crisis in Venezuela". Al Jazeera. 9 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "Cabello en Apure: Decomisamos 12.000 litros de aceites y 30 toneladas de arroz". El-nacional.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "Maduro anunció un sistema de racionamiento". Infobae. 8 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ "Maduro anunció un sistema de racionamiento". La Voz 901(Argentina). 9 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ "Tarjeta de abastecimiento seguro se usará para premiar fidelidad". Últimas Noticias. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ "Gobierno anuncia implementación de Tarjeta de Abastecimiento Seguro". El Universal. 16 March 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Dreier, Hannah (1 April 2014). "Venezuela Takes Dramatic Step Towards Food Rationing". Huffington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Medio Millón Se Inscribe Para La Tarjeta De Abastecimiento Seguro". Runrunes. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ↑ López, Virginia (21 August 2014). "Venezuela to introduce new biometric card in bid to target food smuggling". Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela's Maduro: Fingerprinting at shops is voluntary". BBC News. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ "Maduro ratifica aplicación de control de compras por huellas dactilares". El Universal. 29 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ "Despliegan 17.000 militares para combatir contrabando". El Universal. 11 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela to close Colombia border each night". BBC News. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela to close Colombia border at night to slow smuggling". Reuters. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ "Makro establecerá cupo de venta al mes". Ultimas Noticias. 17 January 2015. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- 1 2 Kurmanaev, Anatoly; Otis, John (3 April 2016). "Water Shortage Cripples Venezuela". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ "Aumentan enfermedades en Venezuela por falta de agua y artículos de higiene". La Crónica de Hoy. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Kai, Daniel; Guanipa, Mircely (22 April 2016). "Venezuela public workers use energy-saving Fridays for TV, shopping". Reuters. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ↑ "Venezuela to ration electricity in power crisis". The Japan Times. 21 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ "Enfrentamientos y barricadas nuevamente en San Cristóbal". El Universal. 25 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Protestan en San Cristóbal en rechazo al captahuellas". El Universal. 25 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- 1 2 "Venezuela respondió al llamado de la MUD y caceroleó contra el sistema biométrico". La Patilla. 28 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- 1 2 "Oposición caceroleó contra las captahuellas". El Mundo. 29 August 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ "MUD reactiva protestas en Venezuela: convoca a un cacerolazo nacional para rechazar sistema biométrico". NTN24. 28 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ↑ "La Mesa convoca a cacerolazo mañana a las 8:00 de la noche". El Universal. 28 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ↑ "Policía dispersa protesta contra el cazahuellas en Zulia #27A (Fotos)". La Patilla. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ↑ Argüelles, Yaileth (28 August 2014). "Polar fustiga uso de las captahuellas". La Verdad. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ↑ Ulmer, Alexandra (29 August 2014). "Shortage-weary Venezuelans scoff at fingerprinting plan for food sales". Reuters. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Zuñiga, Mariana (10 December 2016). "How 'food apartheid' is punishing some Venezuelans". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ "Maduro podría ser dueño de empresa méxicana distribuidora de los CLAP". El Nacional (in Spanish). 23 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Wyss, Jim (23 August 2017). "Venezuela's ex-prosecutor Luisa Ortega accuses Maduro of profiting from nation's hunger". Miami Herald. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Prengaman, Peter (23 August 2017). "Venezuela's ousted prosecutor accuses Maduro of corruption". Associated Press. ABC News. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Campos, Rodrigo (19 April 2018). "U.S., Colombian probe targets Venezuela food import program". Reuters. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ↑ Goodman, Joshua; Alonso Lugo, Luis (19 April 2018). "US officials: 16 nations agree to track Venezuela corruption". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2018-04-19. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- 1 2 "Millonaria incautación de comida con gorgojo que iba a Venezuela". El Tiempo (in Spanish). 17 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ↑ Pons, Corina; Ulmer, Alexandra (8 May 2015). "Venezuela motorbikers are reportedly being killed for scarce spare parts". Business Insider. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- 1 2 Hilder, James (14 June 2016). "Lose weight the Maduro way with a diet of mangos and water". News International Trading Limited. The Times. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ↑ Hernandez, Vladimir. "Going hungry in Venezuela". BBC. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- 1 2 Wajda, Darek Michael. "Hungry Venezuelans Take Desperate Measures in Worsening Crisis". NBC News. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Brodzinsky, Sibylla (24 May 2016). "Food shortages take toll on Venezuelans' diet". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Girl's death from diphtheria highlights Venezuela's health crisis". NBC News. 10 February 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- 1 2 Casey, Nicholas (19 June 2016). "Venezuelans Ransack Stores as Hunger Grips the Nation". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Castro, Maolis (6 March 2017). "La yuca amarga alimenta la muerte en Venezuela". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ↑ "Estragos de la crisis: Ocho niños han muerto en Aragua por consumir yuca amarga". La Patilla (in Spanish). 22 February 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ↑ Guerra, Weildler (8 July 2016). "La dieta de Maduro". El Espectador. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Ocando, Gustavo (8 July 2016). "As Venezuela goes hungry, 'Maduro diet' causes garage sale fever". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- 1 2 "Venebarometro - Diciembre 2016". Scribd. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- 1 2 Pestano, Andrew V. (19 February 2017). "Venezuela: 75% of population lost 19 pounds amid crisis". UPI. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Especial Bloomberg: Al igual que la industria, los hambrientos trabajadores petroleros también se derrumban". La Patilla (in Spanish). 22 February 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 Pablo Peñaloza, Pedro (15 February 2017). "Hungry in Venezuela: 'We were never rich, but we had food'". Univision. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- 1 2 Ulmer, Alexandra (23 March 2017). "Maduro's awkward TV shows raise hackles amid Venezuela crisis". Reuters. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ↑ Pardo, Daniel (23 August 2014). "The malaria mines of Venezuela". BBC. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Faces Health Crisis Amid Shortage of HIV/Aids Medication". Fox News Latino. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Forero, Juan (22 September 2014). "Venezuela Seeks to Quell Fears of Disease Outbreak". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ "En 2014 se registraron 9.286 protestas, cifra inédita en Venezuela". La Patilla. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 Martín, Sabrina (6 August 2015). "Looting Sweeps Venezuela as Hunger Takes Over 132 Incidents Tell of "Desperation and Discomfort" Sinking In". PanAm Post. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- 1 2 Oré, Diego (6 August 2015). "Looting and violence on the rise in Venezuela supermarkets". Reuters. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "How videos of supermarket raids show what life is like in Venezuela". BBC News. 13 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ "Looting Turns Deadly In Venezuela Amid Severe Food Shortages". Huffington Post. 1 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- 1 2 Pardo, Daniel (27 May 2015). "Why Venezuelans worry more about food than crime". BBC News. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Ulmer, Alexandra (5 October 2017). "ENFOQUE- La agitación política y la escasez pasan factura psicológica a los niños de Venezuela". Reuters (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ "Sexo por comida: las niñas venezolanas que se prostituyen para saciar el hambre | El Cooperante". El Cooperante (in Spanish). 1 November 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ↑ "Las diez claves de la escasez en Venezuela". La Patilla. 8 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ "Delcy Rodriguez: No humanitarian crisis in Venezuela". Al Jazeera. 9 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ↑ "To combat hunger, Venezuelans in the U.S. ship food to relatives". Los Angeles Times. 22 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ↑ Graham-Harrison, Emma (26 August 2017). "Hunger eats away at Venezuela's soul as its people struggle to survive". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 Dreier, Hannah (7 August 2015). "VENEZUELA'S TOP BEER SCARCE AMID HEAT WAVE". Associated Press. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ↑ "Desapareció la carne de res en supermercados de Caracas". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Son 17 los productos que están más escasos". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Usuarios creen que escasez persistirá, aún sin colas". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Escasez de Mostaza y Leche condensada". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Venezuelan Inflation Spoils Christmas Tradition". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Sugar shortage cuts Coca-Cola production in Venezuela". BBC. 24 May 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Shortages in Venezuela mean priests are running out of Hosts". Catholic News Agency. 15 August 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Aceite de maíz y girasol lidera niveles de escasez". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Empresarios venezolanos alertan del aumento en la escasez de los 25 productos regulados por el gobierno - LaPatilla.com". La Patilla (in Spanish). 23 August 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ "En Venezuela falta de todo". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "No flour? No fish? Venezuela's chefs get creative amid shortages". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ Pons, Corina (6 January 2014). "McDonald's In Venezuela Have Run Out Of French Fries". Business Insider. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Escasez en Venezuela: faltan frutas, legumbres y hortalizas". Infobae. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Miroff, Nick (31 December 2014). "Venezuela faces ice cream shortage". Concord Monitor. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Paralizada producción de avena y jugos por falta de materia prima". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 "La cruzada de los diabéticos". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Prevén escasez de pan de jamón para diciembre". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Por la escasez de alimentos, Venezuela cambia petróleo por arroz". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 ""Turismo de mercado" hacen en Margarita". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ Noriega, Roger. "Venezuela's health crisis, including Zika outbreak, threatens the region". American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ↑ Díaz Favela, Verónica (28 May 2013). "La escasez venezolana afecta a la Iglesia por falta de vino para las misas". CNN. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Krygier, Rachelle (8 March 2018). "Venezuela faces a terrible new crisis: A critical shortage of blood". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Los antibióticos se consiguen con dificultad". El Tiempo. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Montilla K., Andrea (23 January 2014). "Crisis hospitalaria afecta formación de médicos". El Nacional. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Venezolanos no pueden costear los pocos medicamentos que se encuentra". La Patilla (in Spanish). 16 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- 1 2 "¡Protegerse es un lujo! Anticonceptivos y preservativos se suman a la escasez". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Comienzan a escasear los implantes de seno". Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ Contrera A., Carolina (9 October 2013). "Alertan de ausencia de medicamentos para quimioterapia en el país". El Universal. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "Hospital en Venezuela deja a niños sin quimioterapia por falta de insumos". El Venezolano. 19 May 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- 1 2 "El tic-tac de la hambruna". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 "El 2015 inicia con acentuada escasez en Venezuela: no hay carne, pollo, cepillo dental, ni batería para carros". NTN24. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hernandez, Alicia (9 January 2015). "Basic Medications — and Breast Implants — in Short Supply in Deepening Venezuela Crisis". Vice News. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Brianna (14 August 2015). "Venezuela Healthcare Crisis: Under Maduro, Medical Shortages Reaching Critical Level". International Business Times. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ↑ "Atamel y Eutirox, los medicamentos más buscados". Union Radio. 10 October 2014. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "Venezolanas al natural por escasez de maquillaje". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela en crisis por falta de medicinas". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Es el venezolano el que llega a vendernos productos y gasolina". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "¿Cuál es la verdadera dimensión de la escasez en Venezuela?". El Comercio. 14 May 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Venezuela importará productos de higiene personal ante la escasez nacional". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Sin detergente ni cloro la gente tendrá que lavar con pura agua". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 "Cámara de Construcción asegura que la escasez de cabillas, cemento y acero ha afectado la producción de la Misión Vivienda Venezuela". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "VENEZUELA: Pasan roncha para conseguir cauchos". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Se estima que escasez de repuestos para carros oscila entre 50% y 60%". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Gupta, Girish (16 June 2014). "In Venezuela's funeral industry, a shortage of coffins". Reuters. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ Silvino, Sara (22 April 2014). "Venezuela: garrafas de gás para uso doméstico e alimentos suscitam longas horas de fila". Tribuna da Madeira.

- ↑ "Gasoline Lines Get Longer in Venezuela". Voice of America. 21 September 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ "VENEZUELA: CNP Aragua: Falta de papel en periódicos reduce los espacios informativos". Retrieved 25 August 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shortages in Venezuela. |

News articles, reports and essays

- Cubillos, Ariana (12 July 2016). "Venezuela crisis forces life to wait in line". CBS News. Retrieved 14 July 2016.