Metformin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛtˈfɔːrmɪn/, met-FOR-min |

| Trade names | Glucophage, other |

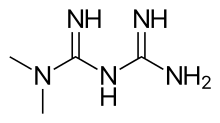

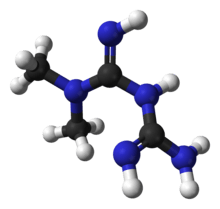

| Synonyms | N,N-dimethylbiguanide[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a696005 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50–60%[2][3] |

| Protein binding | Minimal[2] |

| Metabolism | Not by liver[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 4–8.7 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Urine (90%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.010.472 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C4H11N5 |

| Molar mass | 129.16364 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.3±0.1[4] g/cm3 |

| |

| |

Metformin, marketed under the trade name Glucophage among others, is the first-line medication for the treatment of type 2 diabetes,[5][6] particularly in people who are overweight.[7] It is also used in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).[5] Limited evidence suggests metformin may prevent the cardiovascular disease and cancer complications of diabetes.[8][9] It is not associated with weight gain.[9] It is taken by mouth.[5]

Metformin is generally well tolerated.[10] Common side effects include diarrhea, nausea and abdominal pain.[5] It has a low risk of causing low blood sugar.[5] High blood lactic acid level is a concern if the medication is prescribed inappropriately and in overly large doses.[11] It should not be used in those with significant liver disease or kidney problems.[5] While no clear harm comes from use during pregnancy, insulin is generally preferred for gestational diabetes.[5][12] Metformin is in the biguanide class.[5] It works by decreasing glucose production by the liver and increasing the insulin sensitivity of body tissues.[5]

Metformin was discovered in 1922.[13] French physician Jean Sterne began study in humans in the 1950s.[13] It was introduced as a medication in France in 1957 and the United States in 1995.[5][14] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[15] Metformin is believed to be the most widely used medication for diabetes which is taken by mouth.[13] It is available as a generic medication.[5] The wholesale price in the developed world was between US$0.21 and US$5.55 per month as of 2014.[16] In the United States, it costs US$5 to US$25 per month.[5]

Medical uses

Metformin is primarily used for type 2 diabetes, but is increasingly being used in polycystic ovary syndrome due to the linkage between these two conditions.[5][17] Outcomes appear to be improved even in those with some degree of kidney disease, heart failure, or liver problems.[18]

Type 2 diabetes

The American Diabetes Association and the American College of Physicians each recommend metformin as a first-line agent to treat type 2 diabetes.[19][20][21]

Efficacy

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study, a large clinical trial performed in 1980-90s, provided evidence that metformin reduced the rate of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes relative to other antihyperglycemic agents.[22] However, accumulated evidence from other and more recent trials reduced confidence in the efficacy of metformin for cardiovascular disease prevention.[23][24]

Treatment guidelines for major professional associations including the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, the European Society for Cardiology and the American Diabetes Association, now describe evidence for the cardiovascular benefits of metformin as equivocal.[20][25]

In 2017, the American College of Physicians's guidelines were updated to recognize metformin as the first-line treatment for type-2 diabetes. These guidelines supersede earlier reviews. For example, a 2014 review found tentative evidence that people treated with sulfonylureas had a higher risk of severe low blood sugar events (RR 5.64), though their risk of non-fatal cardiovascular events was lower than the risk of those treated with metformin (RR 0.67). There was not enough data available at that time to determine the relative risk of death or of death from heart disease.[26]

Metformin has little or no effect on body weight in type 2 diabetes compared with placebo,[27] in contrast to sulfonylureas which are associated with weight gain.[27] There is some evidence that metformin is associated with weight loss in obesity in the absence of diabetes.[28][29] Metformin has a lower risk of hypoglycemia than the sulfonylureas,[30][31] although hypoglycemia has uncommonly occurred during intense exercise, calorie deficit, or when used with other agents to lower blood glucose.[32][33] Metformin modestly reduces LDL and triglyceride levels.[30][31]

Prediabetes

Metformin treatment of people at a prediabetes stage of risk for type 2 diabetes may decrease their chances of developing the disease, although intensive physical exercise and dieting work significantly better for this purpose. In a large U.S. study known as the Diabetes Prevention Program, participants were divided into groups and given either placebo, metformin, or lifestyle intervention and followed for an average of three years.

The intensive program of lifestyle modifications included a 16-lesson training on dieting and exercise followed by monthly individualized sessions with the goals of decreasing weight by 7% and engaging in physical activity for at least 150 minutes per week.

The incidence of diabetes was 58% lower in the lifestyle group and 31% lower in individuals given metformin. Among younger people with a higher body mass index, lifestyle modification was no more effective than metformin, and for older individuals with a lower body mass index, metformin was no better than placebo in preventing diabetes.[34] After ten years, the incidence of diabetes was 34% lower in the group of participants given diet and exercise and 18% lower in those given metformin.[35] It is unclear whether metformin slowed down the progression of prediabetes to diabetes (true preventative effect), or the decrease of diabetes in the treated population was simply due to its glucose-lowering action (treatment effect).[36]

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Antidiabetic therapy has been proposed as a treatment for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a condition frequently associated with insulin resistance, since the late 1980s.[37][38]

The use of metformin in PCOS was first reported in 1994, in a small study conducted at the University of the Andes, Venezuela.[39] The United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommended in 2004 that women with PCOS and a body mass index above 25 be given metformin for anovulation and infertility when other therapies fail to produce results.[40] However, two clinical studies completed in 2006–2007 returned mostly negative results, with metformin performing no better than placebo, and a metformin-clomifene combination no better than clomifene alone.[41][42] Reflecting this, subsequent reviews large randomized controlled trials in general have not shown the promise suggested by the early studies.

UK and international clinical practice guidelines do not recommend metformin as a first-line treatment[43] or do not recommend it at all, except for women with glucose intolerance.[44] The guidelines suggest clomiphene as the first medication option and emphasize lifestyle modification independently from medical treatment. Metformin treatment decreases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with PCOS who exhibited impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) at baseline.[38][45]

Female infertility

Metformin or clomiphene are both first line treatments for infertility in women with PCOS.[46] In a dissenting opinion, a systematic review of four head-to-head comparative trials of metformin and clomifene found them equally effective for infertility.[47]

Four positive studies of metformin were in women not responding to clomifene, while the population in the negative studies was drug-naive or uncontrolled for the previous treatment. Metformin should be used as a second-line medication if clomifene treatment fails.[48] Another review recommended metformin unreservedly as a first-line treatment option because it has positive effects not only on anovulation, but also on insulin resistance, hirsutism and obesity often associated with PCOS.[46] A Cochrane review found metformin improves ovulation and pregnancy rates, particularly when combined with clomifene, and tentative evidence that it may increase the number of live births.[49]

The use of metformin during all parts of pregnancy is controversial.[50] One review found that when taken during pregnancy it reduces the number of complications during pregnancy and does not appear to cause developmental delays.[51] Another review found good short term safety for both the mother and baby but unclear long term safety.[52]

Metformin use among women with PCOS before they are pregnant does not appear to reduce abortion risk.[53]

Gestational diabetes

Several observational studies and randomized, controlled trials found metformin to be as effective and safe as insulin for the management of gestational diabetes.[54][55]

Nonetheless, several concerns were raised and evidence on the long-term safety of metformin for both mother and child is lacking.[56]

Metformin is safe in pregnancy and women with gestational diabetes treated with metformin have less weight gain during pregnancy than those treated with insulin.[56] Babies born to women treated with metformin have been found to develop less visceral fat, making them less prone to insulin resistance in later life.[57]

Other

Metformin appears to be safe and effective in counteracting the weight gain caused by the antipsychotic medications olanzapine and clozapine.[58][59] Although modest reversal of clozapine-associated weight gain is found with metformin, primary prevention of weight gain is more valuable.[60]

Metformin may reduce the insulin requirement in type 1 diabetes.[61]

Contraindications

Metformin is contraindicated in people with any condition that could increase the risk of lactic acidosis, including kidney disorders (arbitrarily defined as creatinine levels over 150 μmol/l (1.7 mg/dl)[62]), lung disease and liver disease. According to the prescribing information, heart failure (in particular, unstable or acute congestive heart failure) increases the risk of lactic acidosis with metformin.[63] A 2007 systematic review of controlled trials, however, suggested metformin is the only antidiabetic medication not associated with any measurable harm in people with heart failure, and it may reduce mortality in comparison with other antidiabetic agents.[64]

Metformin is recommended to be temporarily discontinued before any radiographic study involving iodinated contrast agents, (such as a contrast-enhanced CT scan or angiogram), as the contrast dye may temporarily impair kidney function, indirectly leading to lactic acidosis by causing retention of metformin in the body.[65][66] Metformin can be resumed after two days, assuming kidney function is normal.[65][66]

Adverse effects

The most common adverse effect of metformin is gastrointestinal irritation, including diarrhea, cramps, nausea, vomiting, and increased flatulence; metformin is more commonly associated with gastrointestinal side effects than most other antidiabetic medications.[31] The most serious potential side effect of metformin use is lactic acidosis; this complication is very rare, and the vast majority of these cases seem to be related to comorbid conditions, such as impaired liver or kidney function, rather than to the metformin itself.[67]

Metformin has also been reported to decrease the blood levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone in people with hypothyroidism.[68] The significance of this is still unknown.

Gastrointestinal

In a clinical trial of 286 subjects, 53.2% of the 141 given immediate-release metformin (as opposed to placebo) reported diarrhea, versus 11.7% for placebo, and 25.5% reported nausea/vomiting, versus 8.3% for those on placebo.[69]

Gastrointestinal upset can cause severe discomfort; it is most common when metformin is first administered, or when the dose is increased. The discomfort can often be avoided by beginning at a low dose (1.0 to 1.7 grams per day) and increasing the dose gradually but even with low doses 5% of people may be unable to tolerate metformin.[70] Use of slow- or extended-release preparations may improve tolerability.[70]

Long-term use of metformin has been associated with increased homocysteine levels[71] and malabsorption of vitamin B12.[72][73] Higher doses and prolonged use are associated with increased incidence of vitamin B12 deficiency,[74] and some researchers recommend screening or prevention strategies.[75]

Lactic acidosis

The most serious potential adverse effect of biguanide use is metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA). Though the incidence for MALA is about nine per 100,000 person-years,[76] this is similar to the background incidence of lactic acidosis in the general population. A systematic review concluded no data exists to definitively link metformin to lactic acidosis.[77] Lactic acidosis can be fatal.

Phenformin, another biguanide, was withdrawn from the market because of an increased risk of lactic acidosis (rate of 40-64 per 100,000 patient-years).[76] However, metformin is safer than phenformin, and the risk of developing lactic acidosis is not increased except for known high-risk groups.[77]

Lactate uptake by the liver is diminished with metformin administration because lactate is a substrate for hepatic gluconeogenesis, a process that metformin inhibits. In healthy individuals, this slight excess is cleared by other mechanisms (including uptake by unimpaired kidneys), and no significant elevation in blood levels of lactate occurs.[30] Given impaired kidney function, clearance of metformin and lactate is reduced, increasing levels of both, and possibly causing lactic acid buildup. Because metformin decreases liver uptake of lactate, any condition that may precipitate lactic acidosis is a contraindication. Common causes include alcoholism (due to depletion of NAD+ stores), heart failure and respiratory disease (due to inadequate tissue oxygenation); the most common cause is kidney disease.[78]

Metformin has been suggested as increasing production of lactate in the large intestine, which could potentially contribute to lactic acidosis in those with risk factors.[79] However, the clinical significance of this is unknown, and the risk of metformin-associated lactic acidosis is most commonly attributed to decreased hepatic uptake rather than increased intestinal production.[30][78][80]

Lactic acidosis is initially treated with sodium bicarbonate, although high doses are not recommended, as this may increase intracellular acidosis.[81] Acidosis that does not respond to administration of sodium bicarbonate may require further management with standard hemodialysis or continuous venovenous hemofiltration.

Overdose

A review of metformin overdoses reported to poison control centers over a five-year period found serious adverse events were rare, though the elderly appeared to be at greater risk.[82] A similar study in which cases were reported to Texas poison control centers between 2000 and 2006 found ingested doses of more than 5,000 mg were more likely to involve serious medical outcomes in adults.[83] Survival following intentional overdoses with up to 63,000 mg (63 g) of metformin have been reported.[84] Fatalities following overdose are rare.[81][85][86] In healthy children, unintentional doses of less than 1,700 mg are unlikely to cause significant toxic effects.[87]

The most common symptoms following overdose include vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, tachycardia, drowsiness, and, rarely, hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia.[83][86] Treatment of metformin overdose is generally supportive, as no specific antidote is known. Extracorporeal treatments are recommended in severe overdoses.[88] Due to metformin's low molecular weight and lack of plasma protein binding, these techniques have the benefit of removing metformin from blood plasma, preventing further lactate overproduction.[88]

Metformin may be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum to monitor therapy, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or assist in a forensic death investigation. Blood or plasma metformin concentrations are usually in a range of 1–4 mg/l in persons receiving therapeutic doses, 40–120 mg/l in victims of acute overdosage, and 80–200 mg/l in fatalities. Chromatographic techniques are commonly employed.[89][90]

Interactions

The H2-receptor antagonist cimetidine causes an increase in the plasma concentration of metformin by reducing clearance of metformin by the kidneys;[91] both metformin and cimetidine are cleared from the body by tubular secretion, and both, particularly the cationic (positively charged) form of cimetidine, may compete for the same transport mechanism.[92] A small double-blind, randomized study found the antibiotic cephalexin to also increase metformin concentrations by a similar mechanism;[93] theoretically, other cationic medications may produce the same effect.[92]

Metformin also interacts with anticholinergic medications, due to their effect on gastric motility. Anticholinergic drugs reduce gastric motility, prolonging the time drugs spend in the gastrointestinal tract. This impairment may lead to more metformin being absorbed than without the presence of an anticholinergic drug, thereby increasing the concentration of metformin in the plasma and increasing the risk for adverse effects.[94]

Mechanism of action

Metformin's main effect is to decrease liver glucose production.[79] It also has an insulin-sensitizing effect with multiple actions on tissues including the liver, skeletal muscle, endothelium, adipose tissue, and the ovary.[38][95]

Metformin decreases high blood sugar, primarily by suppressing liver glucose production (hepatic gluconeogenesis).[79] The average patient with type 2 diabetes has three times the normal rate of gluconeogenesis; metformin treatment reduces this by over one-third.[96] The molecular mechanism of metformin is incompletely understood. Multiple potential mechanisms of action have been proposed, including; inhibition of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (complex I), activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), inhibition of glucagon-induced elevation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) with reduced activation of protein kinase A (PKA), inhibition of mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase, and an effect on gut microbiota.[97][98][99]

Activation of AMPK was required for metformin's inhibitory effect on liver glucose production.[100] AMPK is an enzyme that plays an important role in insulin signaling, whole body energy balance and the metabolism of glucose and fats.[101] AMPK Activation was required for an increase in the expression of small heterodimer partner, which in turn inhibited the expression of the hepatic gluconeogenic genes phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose 6-phosphatase.[102] Metformin is frequently used in research along with AICA ribonucleotide as an AMPK agonist. Mouse models in which the genes for AMPKα1 and α2 catalytic subunits (Prkaa1/2) or LKB1, an upstream kinase of AMPK, had been knocked out in hepatocytes, have raised doubts over the role of AMPK, since the effect of metformin was not abolished by loss of AMPK function.[97] The mechanism by which biguanides increase the activity of AMPK remains uncertain; however, metformin increases the concentration of cytosolic adenosine monophosphate (AMP) (as opposed to a change in total AMP or total AMP/adenosine triphosphate).[103] Increased cellular AMP has been proposed to explain the inhibition of glucagon-induced increase in cAMP and activation of PKA.[97] Metformin and other biguanides may antagonize the action of glucagon, thus reducing fasting glucose levels.[104] Metformin also induces a profound shift in the faecal microbial community profile in diabetic mice and this may contribute to its mode of action possibly through an effect on glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion.[98]

In addition to suppressing hepatic glucose production, metformin increases insulin sensitivity, enhances peripheral glucose uptake (by inducing the phosphorylation of GLUT4 enhancer factor), decreases insulin-induced suppression of fatty acid oxidation,[105] and decreases absorption of glucose from the gastrointestinal tract. Increased peripheral use of glucose may be due to improved insulin binding to insulin receptors.[106] The increase in insulin binding after metformin treatment has also been demonstrated in patients with NIDDM.[107]

AMPK probably also plays a role in increased peripheral insulin sensitivity, as metformin administration increases AMPK activity in skeletal muscle.[108] AMPK is known to cause GLUT4 deployment to the plasma membrane, resulting in insulin-independent glucose uptake. Some metabolic actions of metformin do appear to occur by AMPK-independent mechanisms; the metabolic actions of metformin in the heart muscle can occur independent of changes in AMPK activity and may be mediated by p38 MAPK- and PKC-dependent mechanisms.[109]

Chemistry

The usual synthesis of metformin, originally described in 1922, involves the one-pot reaction of dimethylamine hydrochloride and 2-cyanoguanidine over heat.[110][111]

According to the procedure described in the 1975 Aron patent,[112] and the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia,[113] equimolar amounts of dimethylamine and 2-cyanoguanidine are dissolved in toluene with cooling to make a concentrated solution, and an equimolar amount of hydrogen chloride is slowly added. The mixture begins to boil on its own, and after cooling, metformin hydrochloride precipitates with a 96% yield.

Pharmacokinetics

Metformin has an oral bioavailability of 50–60% under fasting conditions, and is absorbed slowly.[92][114] Peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) are reached within one to three hours of taking immediate-release metformin and four to eight hours with extended-release formulations.[92][114] The plasma protein binding of metformin is negligible, as reflected by its very high apparent volume of distribution (300–1000 l after a single dose). Steady state is usually reached in one or two days.[92]

Metformin has acid dissociation constant values (pKa) of 2.8 and 11.5, so exists very largely as the hydrophilic cationic species at physiological pH values. The metformin pKa values make metformin a stronger base than most other basic medications with less than 0.01% nonionized in blood. Furthermore, the lipid solubility of the nonionized species is slight as shown by its low logP value (log(10) of the distribution coefficient of the nonionized form between octanol and water) of -1.43. These chemical parameters indicate low lipophilicity and, consequently, rapid passive diffusion of metformin through cell membranes is unlikely. As a result of its low lipid solubility it requires the transporter SLC22A1 in order for it to enter cells.[115][116] The logP of metformin is less than that of phenformin (-0.84) because two methyl substituents on metformin impart lesser lipophilicity than the larger phenylethyl side chain in phenformin. More lipophilic derivatives of metformin are presently under investigation with the aim of producing prodrugs with superior oral absorption than metformin.[117]

Metformin is not metabolized. It is cleared from the body by tubular secretion and excreted unchanged in the urine; metformin is undetectable in blood plasma within 24 hours of a single oral dose.[92][118] The average elimination half-life in plasma is 6.2 hours.[92] Metformin is distributed to (and appears to accumulate in) red blood cells, with a much longer elimination half-life: 17.6 hours[92] (reported as ranging from 18.5 to 31.5 hours in a single-dose study of nondiabetics).[118]

History

The biguanide class of antidiabetic medications, which also includes the withdrawn agents phenformin and buformin, originates from the French lilac or goat's rue (Galega officinalis), a plant used in folk medicine for several centuries.[119]

Metformin was first described in the scientific literature in 1922, by Emil Werner and James Bell, as a product in the synthesis of N,N-dimethylguanidine.[110] In 1929, Slotta and Tschesche discovered its sugar-lowering action in rabbits, finding it the most potent biguanide analog they studied.[120] This result was completely forgotten, as other guanidine analogs, such as the synthalins, took over and were themselves soon overshadowed by insulin.[121]

Interest in metformin resumed at the end of the 1940s. In 1950, metformin, unlike some other similar compounds, was found not to decrease blood pressure and heart rate in animals.[122] That year, Filipino physician Eusebio Y. Garcia[123] used metformin (he named it Fluamine) to treat influenza; he noted the medication "lowered the blood sugar to minimum physiological limit" and was not toxic. Garcia believed metformin to have bacteriostatic, antiviral, antimalarial, antipyretic and analgesic actions.[124] In a series of articles in 1954, Polish pharmacologist Janusz Supniewski[125] was unable to confirm most of these effects, including lowered blood sugar. Instead he observed antiviral effects in humans.[126][127]

French diabetologist Jean Sterne studied the antihyperglycemic properties of galegine, an alkaloid isolated from Galega officinalis, which is related in structure to metformin and had seen brief use as an antidiabetic before the synthalins were developed.[128] Later, working at Laboratoires Aron in Paris, he was prompted by Garcia's report to reinvestigate the blood sugar-lowering activity of metformin and several biguanide analogs. Sterne was the first to try metformin on humans for the treatment of diabetes; he coined the name "Glucophage" (glucose eater) for the medication and published his results in 1957.[121][128]

Metformin became available in the British National Formulary in 1958. It was sold in the UK by a small Aron subsidiary called Rona.[129]

Broad interest in metformin was not rekindled until the withdrawal of the other biguanides in the 1970s. Metformin was approved in Canada in 1972,[130] but did not receive approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for type 2 diabetes until 1994.[131] Produced under license by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Glucophage was the first branded formulation of metformin to be marketed in the U.S., beginning on March 3, 1995.[132] Generic formulations are now available in several countries, and metformin is believed to have become the world's most widely prescribed antidiabetic medication.[128]

Formulations

The name "Metformin" is the BAN, USAN and INN for the medication. It is sold under several trade names, including Glucophage XR, Carbophage SR, Riomet, Fortamet, Glumetza, Obimet, Gluformin, Dianben, Diabex, Diaformin, Siofor, Metfogamma and Glifor.

Liquid metformin is sold under the name Riomet in India. Each 5 ml of Riomet is equivalent to the 500-mg tablet form.[133]

Metformin IR (immediate release) is available in 500, 850, and 1000-mg tablets. All of these are available as generic medications in the U.S.

Metformin SR (slow release) or XR (extended release) was introduced in 2004. It is available in 500, 750, and 1000-mg strengths, mainly to counteract common gastrointestinal side effects, as well as to increase compliance by reducing pill burden. No difference in effectiveness exists between the two preparations.

Combination with other medications

When used for type 2 diabetes, metformin is often prescribed in combination with other medications.

Several are available as fixed-dose combinations, to reduce pill burden and simplify administration.[134]

Rosiglitazone

A combination of metformin and rosiglitazone was released in 2002 and sold as Avandamet by GlaxoSmithKline.[135]

By 2009 it had become the most popular metformin combination.[136]

In 2005, the stock of Avandamet was removed from the market, after inspections showed the factory where it was produced was violating good manufacturing practices.[137] The medication pair continued to be prescribed separately and Avandamet was again available by the end of that year. A generic formulation of metformin/rosiglitazone from Teva received tentative approval from the FDA and reached the market in early 2012.[138]

However, following a meta-analysis in 2007 that linked the medication's use to an increased risk of heart attack,[139] concerns were raised over the safety of medicines containing rosiglitazone. In September 2010 the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended that the medication be suspended from the European market because the benefits of rosiglitazone no longer outweighed the risks.[140][141]

It was withdrawn from the market in the UK and India in 2010,[142] and in New Zealand and South Africa in 2011.[143] From November 2011 until November 2013 the FDA[144] did not allow rosiglitazone or metformin/rosiglitazone to be sold without a prescription; moreover, makers were required to notify patients of the risks associated with its use, and the drug had to be purchased by mail order through specified pharmacies.[145]

In November 2013, the FDA lifted its earlier restrictions on rosiglitazone after reviewing the results of the 2009 RECORD clinical trial (a six-year, open label randomized control trial), which failed to show elevated risk of heart attack or death associated with the medication.[146][147][148]

Pioglitazone

The combination of metformin and pioglitazone (Actoplus Met, Piomet, Politor) remains available in U.S. and Europe.[149][150]

DPP-4 inhibitors

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors inhibit dipeptidyl peptidase-4 and thus reduce glucagon and blood glucose levels.

DPP-4 inhibitors combined with metformin include a sitagliptin/metformin combination and a saxagliptin combination (Komboglyze), and with alogliptin as Kazano among others.

In Europe, Canada, and elsewhere metformin combined with linagliptin is marketed under the trade name Jentadueto.[151]

Sulfonylureas

Sulfonylureas act by increasing insulin release from the beta cells in the pancreas. Metformin is available combined with the sulfonylureas glipizide (Metaglip) and glibenclamide (US: glyburide) (Glucovance).

Generic formulations of metformin/glipizide and metformin/glibenclamide are available (the latter is more popular).[152]

Meglitinide

Meglitinides are similar to sulfonylureas.

A repaglinide/metformin combination is sold as Prandimet.

Triple combination

The combination of metformin with pioglitazone and glibenclamide[153] is available in India as Triformin.

Research

Metformin has been studied for its effects on multiple other conditions, including:

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.[154][155][156]

- Premature puberty.[156][157]

- Cancer.[158][159]

- Cardiovascular disease in people with diabetes.[160]

- Aging (C. elegans and crickets).[116] A 2017 review found that people with diabetes who were taking metformin had lower all-cause mortality. They also had reduced cancer and cardiovascular disease compared with those on other therapies.[160] As of 2016 it is being studied to see what effect it may have on aging.[161]

See also

References

- ↑ Sirtori CR, Franceschini G, Galli-Kienle M, Cighetti G, Galli G, Bondioli A, Conti F (December 1978). "Disposition of metformin (N,N-dimethylbiguanide) in man". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 24 (6): 683–93. doi:10.1002/cpt1978246683. PMID 710026.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dunn CJ, Peters DH (May 1995). "Metformin. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus". Drugs. 49 (5): 721–49. doi:10.2165/00003495-199549050-00007. PMID 7601013.

- ↑ Hundal RS, Inzucchi SE (2003). "Metformin: new understandings, new uses". Drugs. 63 (18): 1879–94. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363180-00001. PMID 12930161.

- ↑ "metformin_msds".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Metformin Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ↑ Maruthur NM, Tseng E, Hutfless S, Wilson LM, Suarez-Cuervo C, Berger Z, Chu Y, Iyoha E, Segal JB, Bolen S (June 2016). "Diabetes Medications as Monotherapy or Metformin-Based Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (11): 740–51. doi:10.7326/M15-2650. PMID 27088241.

- ↑ Clinical Obesity (2nd ed.). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. 2008. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-470-98708-7. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Malek M, Aghili R, Emami Z, Khamseh ME (September 2013). "Risk of cancer in diabetes: the effect of metformin". ISRN Endocrinology. 2013: 636927. doi:10.1155/2013/636927. PMC 3800579. PMID 24224094.

- 1 2 "Type 2 diabetes and metformin. First choice for monotherapy: weak evidence of efficacy but well-known and acceptable adverse effects". Prescrire International. 23 (154): 269–72. November 2014. PMID 25954799.

- ↑ Triggle CR, Ding H (January 2017). "Metformin is not just an antihyperglycaemic drug but also has protective effects on the vascular endothelium". Acta Physiologica. 219 (1): 138–151. doi:10.1111/apha.12644. PMID 26680745.

- ↑ Lipska KJ, Bailey CJ, Inzucchi SE (June 2011). "Use of metformin in the setting of mild-to-moderate renal insufficiency". Diabetes Care. 34 (6): 1431–7. doi:10.2337/dc10-2361. PMC 3114336. PMID 21617112.

- ↑ Lautatzis ME, Goulis DG, Vrontakis M (November 2013). "Efficacy and safety of metformin during pregnancy in women with gestational diabetes mellitus or polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review". Metabolism. 62 (11): 1522–34. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2013.06.006. PMID 23886298.

- 1 2 3 Fischer, Janos (2010). Analogue-based Drug Discovery II. John Wiley & Sons. p. 49. ISBN 978-3-527-63212-1. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ McKee, Mitchell Bebel Stargrove, Jonathan Treasure, Dwight L. (2008). Herb, nutrient, and drug interactions : clinical implications and therapeutic strategies. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-323-02964-3. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Metformin". Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ↑ Lord JM, Flight IH, Norman RJ (October 2003). "Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 327 (7421): 951–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7421.951. PMC 259161. PMID 14576245.

- ↑ Crowley MJ, Diamantidis CJ, McDuffie JR, Cameron CB, Stanifer JW, Mock CK, Wang X, Tang S, Nagi A, Kosinski AS, Williams JW (February 2017). "Clinical Outcomes of Metformin Use in Populations With Chronic Kidney Disease, Congestive Heart Failure, or Chronic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 166 (3): 191–200. doi:10.7326/M16-1901. PMID 28055049.

- ↑ Bennett WL, Maruthur NM, Singh S, Segal JB, Wilson LM, Chatterjee R, Marinopoulos SS, Puhan MA, Ranasinghe P, Block L, Nicholson WK, Hutfless S, Bass EB, Bolen S (May 2011). "Comparative effectiveness and safety of medications for type 2 diabetes: an update including new drugs and 2-drug combinations". Annals of Internal Medicine. 154 (9): 602–13. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-154-9-201105030-00336. PMC 3733115. PMID 21403054.

- 1 2 Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, Peters AL, Tsapas A, Wender R, Matthews DR (June 2012). "Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD)". Diabetes Care. 35 (6): 1364–79. doi:10.2337/dc12-0413. PMC 3357214. PMID 22517736.

- ↑ Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Sweet DE, Starkey M, Shekelle P (February 2012). "Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 156 (3): 218–31. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00011. PMID 22312141.

- ↑ "Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group". Lancet. 352 (9131): 854–65. September 1998. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07037-8. PMID 9742977.

- ↑ Selvin E, Bolen S, Yeh HC, Wiley C, Wilson LM, Marinopoulos SS, Feldman L, Vassy J, Wilson R, Bass EB, Brancati FL (October 2008). "Cardiovascular outcomes in trials of oral diabetes medications: a systematic review". Archives of Internal Medicine. 168 (19): 2070–80. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.19.2070. PMC 2765722. PMID 18955635.

- ↑ Boussageon R, Supper I, Bejan-Angoulvant T, Kellou N, Cucherat M, Boissel JP, Kassai B, Moreau A, Gueyffier F, Cornu C (2012). "Reappraisal of metformin efficacy in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". PLoS Medicine. 9 (4): e1001204. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001204. PMC 3323508. PMID 22509138.

- ↑ Rydén L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, Berne C, Cosentino F, Danchin N, Deaton C, Escaned J, Hammes HP, Huikuri H, Marre M, Marx N, Mellbin L, Ostergren J, Patrono C, Seferovic P, Uva MS, Taskinen MR, Tendera M, Tuomilehto J, Valensi P, Zamorano JL (May 2014). "ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD - summary". Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research. 11 (3): 133–73. doi:10.1177/1479164114525548. PMID 24800783.

- ↑ Hemmingsen B, Schroll JB, Wetterslev J, Gluud C, Vaag A, Sonne DP, Lundstrøm LH, Almdal T (July 2014). "Sulfonylurea versus metformin monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and trial sequential analysis". CMAJ Open. 2 (3): E162–75. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20130073. PMC 4185978. PMID 25295236.

- 1 2 Johansen, K. (1999). "Efficacy of metformin in the treatment of NIDDM. Meta-analysis". Diabetes Care. 22 (1): 33–37. doi:10.2337/diacare.22.1.33. ISSN 0149-5992.

- ↑ Golay A (January 2008). "Metformin and body weight". International Journal of Obesity. 32 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803695. PMID 17653063.

- ↑ Mead E, Atkinson G, Richter B, Metzendorf MI, Baur L, Finer N, Corpeleijn E, O'Malley C, Ells LJ (November 2016). "Drug interventions for the treatment of obesity in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD012436. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012436. PMID 27899001.

- 1 2 3 4 Maharani U (2009). "Chapter 27: Diabetes Mellitus & Hypoglycemia". In Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ. Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment 2010 (49th ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 1092–93. ISBN 0-07-162444-9.

- 1 2 3 Bolen S, Feldman L, Vassy J, Wilson L, Yeh HC, Marinopoulos S, Wiley C, Selvin E, Wilson R, Bass EB, Brancati FL (September 2007). "Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and safety of oral medications for type 2 diabetes mellitus". Annals of Internal Medicine. 147 (6): 386–99. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00178. PMID 17638715.

- ↑ DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM (2005). Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-141613-7.

- ↑ "Glucophage package insert". Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2009.

- ↑ Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM, et al. (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group) (February 2002). "Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin". The New England Journal of Medicine. 346 (6): 393–403. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012512. PMC 1370926. PMID 11832527.

- ↑ Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Christophi CA, Hoffman HJ, Brenneman AT, Brown-Friday JO, Goldberg R, Venditti E, Nathan DM, et al. (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group) (November 2009). "10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study". Lancet. 374 (9702): 1677–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. PMC 3135022. PMID 19878986.

- ↑ Lily M, Lilly M, Godwin M (April 2009). "Treating prediabetes with metformin: systematic review and meta-analysis". Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien. 55 (4): 363–9. PMC 2669003. PMID 19366942.

- ↑ Kidson W (November 1998). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: a new direction in treatment". The Medical Journal of Australia. 169 (10): 537–40. PMID 9861912. Archived from the original on 2010-01-20.

- 1 2 3 Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Economou F, Palimeri S, Christakou C (September 2010). "Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1205 (1): 192–8. Bibcode:2010NYASA1205..192D. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05679.x. PMID 20840272.

- ↑ Teede H (2007). "Insulin sensitizers in polycystic ovary syndrome". In Kovács GT, Norman RW. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 65–81. ISBN 0-521-84849-0.

- ↑ National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (2004). Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems (pdf). London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. pp. 58–59. ISBN 1-900364-97-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-07-11.

- ↑ Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, Carr BR, Diamond MP, Carson SA, Steinkampf MP, Coutifaris C, McGovern PG, Cataldo NA, Gosman GG, Nestler JE, Giudice LC, Leppert PC, Myers ER (February 2007). "Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (6): 551–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa063971. PMID 17287476.

- ↑ Moll E, Bossuyt PM, Korevaar JC, Lambalk CB, van der Veen F (June 2006). "Effect of clomifene citrate plus metformin and clomifene citrate plus placebo on induction of ovulation in women with newly diagnosed polycystic ovary syndrome: randomised double blind clinical trial". BMJ. 332 (7556): 1485. doi:10.1136/bmj.38867.631551.55. PMC 1482338. PMID 16769748.

- ↑ Balen A (December 2008). "Metformin therapy for the management of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome" (PDF). Scientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 13. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-18. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ↑ The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group (March 2008). "Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome". Human Reproduction. 23 (3): 462–77. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem426. PMID 18308833.

- ↑ Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou CD, Kandaraki E, Economou FN (February 2010). "Metformin: an old medication of new fashion: evolving new molecular mechanisms and clinical implications in polycystic ovary syndrome". European Journal of Endocrinology. 162 (2): 193–212. doi:10.1530/EJE-09-0733. PMID 19841045.

- 1 2 Radosh L (April 2009). "Drug treatments for polycystic ovary syndrome". American Family Physician. 79 (8): 671–6. PMID 19405411.

- ↑ Palomba S, Pasquali R, Orio F, Nestler JE (February 2009). "Clomiphene citrate, metformin or both as first-step approach in treating anovulatory infertility in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a systematic review of head-to-head randomized controlled studies and meta-analysis". Clinical Endocrinology. 70 (2): 311–21. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03369.x. PMID 18691273.

- ↑ Al-Inany H, Johnson N (June 2006). "Drugs for anovulatory infertility in polycystic ovary syndrome". BMJ. 332 (7556): 1461–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7556.1461. PMC 1482323. PMID 16793784.

- ↑ Morley LC, Tang T, Yasmin E, Norman RJ, Balen AH (November 2017). "Insulin-sensitising drugs (metformin, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inositol) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome, oligo amenorrhoea and subfertility". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD003053. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003053.pub6. PMID 29183107.

- ↑ Ghazeeri GS, Nassar AH, Younes Z, Awwad JT (June 2012). "Pregnancy outcomes and the effect of metformin treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an overview". Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 91 (6): 658–78. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01385.x. PMID 22375613.

- ↑ Kumar P, Khan K (May 2012). "Effects of metformin use in pregnant patients with polycystic ovary syndrome". Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences. 5 (2): 166–9. doi:10.4103/0974-1208.101012. PMC 3493830. PMID 23162354.

- ↑ Butalia S, Gutierrez L, Lodha A, Aitken E, Zakariasen A, Donovan L (January 2017). "Short- and long-term outcomes of metformin compared with insulin alone in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Diabetic Medicine. 34 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1111/dme.13150. PMID 27150509.

- ↑ Palomba S, Falbo A, Orio F, Zullo F (November 2009). "Effect of preconceptional metformin on abortion risk in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Fertility and Sterility. 92 (5): 1646–58. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.087. PMID 18937939.

- ↑ Nicholson W, Bolen S, Witkop CT, Neale D, Wilson L, Bass E (January 2009). "Benefits and risks of oral diabetes agents compared with insulin in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 113 (1): 193–205. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318190a459. PMID 19104375.

- ↑ Kitwitee P, Limwattananon S, Limwattananon C, Waleekachonlert O, Ratanachotpanich T, Phimphilai M, Nguyen TV, Pongchaiyakul C (September 2015). "Metformin for the treatment of gestational diabetes: An updated meta-analysis". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 109 (3): 521–32. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2015.05.017. PMID 26117686.

- 1 2 Balsells M, García-Patterson A, Solà I, Roqué M, Gich I, Corcoy R (January 2015). "Glibenclamide, metformin, and insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 350: h102. doi:10.1136/bmj.h102. PMC 4301599. PMID 25609400.

- ↑ Sivalingam VN, Myers J, Nicholas S, Balen AH, Crosbie EJ (2014). "Metformin in reproductive health, pregnancy and gynaecological cancer: established and emerging indications". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (6): 853–68. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu037. PMID 25013215.

- ↑ Choi YJ (2015). "Efficacy of adjunctive treatments added to olanzapine or clozapine for weight control in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". TheScientificWorldJournal. 2015: 970730. doi:10.1155/2015/970730. PMC 4310265. PMID 25664341.

- ↑ Praharaj SK, Jana AK, Goyal N, Sinha VK (March 2011). "Metformin for olanzapine-induced weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 71 (3): 377–82. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03783.x. PMC 3045546. PMID 21284696.

- ↑ Siskind DJ, Leung J, Russell AW, Wysoczanski D, Kisely S (2016). "Metformin for Clozapine Associated Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PloS One. 11 (6): e0156208. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1156208S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156208. PMC 4909277. PMID 27304831.

- ↑ Vella S, Buetow L, Royle P, Livingstone S, Colhoun HM, Petrie JR (May 2010). "The use of metformin in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review of efficacy". Diabetologia. 53 (5): 809–20. doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1636-9. PMID 20057994.

- ↑ Jones GC, Macklin JP, Alexander WD (January 2003). "Contraindications to the use of metformin". BMJ. 326 (7379): 4–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7379.4. PMC 1124930. PMID 12511434.

- ↑ "Glucophage Prescribing Information for the U.S." (PDF). U.S. FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-09-22. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ Eurich DT, McAlister FA, Blackburn DF, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Varney J, Johnson JA (September 2007). "Benefits and harms of antidiabetic agents in patients with diabetes and heart failure: systematic review". BMJ. 335 (7618): 497. doi:10.1136/bmj.39314.620174.80. PMC 1971204. PMID 17761999.

- 1 2 Weir J (March 19, 1999). Guidelines with Regard to Metformin-Induced Lactic Acidosis and X-ray Contrast Medium Agents. Royal College of Radiologists. Retrieved October 26, 2007 through the Internet Archive.

- 1 2 Thomsen HS, Morcos SK (August 2003). "Contrast media and the kidney: European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines". The British Journal of Radiology. 76 (908): 513–8. doi:10.1259/bjr/26964464. PMID 12893691.

- ↑ Khurana R, Malik IS (January 2010). "Metformin: safety in cardiac patients". Heart. 96 (2): 99–102. doi:10.1136/hrt.2009.173773. PMID 19564648.

- ↑ Vigersky RA, Filmore-Nassar A, Glass AR (January 2006). "Thyrotropin suppression by metformin". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 91 (1): 225–7. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1210. PMID 16219720.

- ↑ Drug Facts and Comparisons 2005. St. Louis, Mo: Facts and Comparisons. October 2004. ISBN 1-57439-193-3.

- 1 2 Fujita Y, Inagaki N (January 2017). "Metformin: New Preparations and Nonglycemic Benefits". Current Diabetes Reports. 17 (1): 5. doi:10.1007/s11892-017-0829-8. PMID 28116648.

- ↑ Wulffelé MG, Kooy A, Lehert P, Bets D, Ogterop JC, Borger van der Burg B, Donker AJ, Stehouwer CD (November 2003). "Effects of short-term treatment with metformin on serum concentrations of homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial". Journal of Internal Medicine. 254 (5): 455–63. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01213.x. PMID 14535967.

- ↑ Andrès E, Noel E, Goichot B (October 2002). "Metformin-associated vitamin B12 deficiency". Archives of Internal Medicine. 162 (19): 2251–2. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.19.2251-a. PMID 12390080.

- ↑ Gilligan MA (February 2002). "Metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency". Archives of Internal Medicine. 162 (4): 484–5. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.4.484. PMID 11863489.

- ↑ de Jager J, Kooy A, Lehert P, Wulffelé MG, van der Kolk J, Bets D, Verburg J, Donker AJ, Stehouwer CD (May 2010). "Long term treatment with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency: randomised placebo controlled trial". BMJ. 340: c2181. doi:10.1136/bmj.c2181. PMC 2874129. PMID 20488910.

- ↑ Ting RZ, Szeto CC, Chan MH, Ma KK, Chow KM (October 2006). "Risk factors of vitamin B(12) deficiency in patients receiving metformin". Archives of Internal Medicine. 166 (18): 1975–9. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.18.1975. PMID 17030830.

- 1 2 Stang M, Wysowski DK, Butler-Jones D (June 1999). "Incidence of lactic acidosis in metformin users". Diabetes Care. 22 (6): 925–7. doi:10.2337/diacare.22.6.925. PMID 10372243.

- 1 2 Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE (November 2003). "Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (21): 2594–602. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.21.2594. PMID 14638559.

- 1 2 Shu AD, Myers MG, Shoelson SE (2005). "Chapter 29: Pharmacology of the Endocrine Pancreas". In Golan ED, Tashjian AH, Armstrong EJ, Galanter JM, Armstrong AW, Arnaout RA, Rose HS. Principles of pharmacology: the pathophysiologic basis of drug therapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. pp. 540–41. ISBN 0-7817-4678-7.

- 1 2 3 Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR (July 2002). "Metformin: an update". Annals of Internal Medicine. 137 (1): 25–33. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00009. PMID 12093242.

- ↑ Davis SN (2006). "Chapter 60: Insulin, Oral Hypoglycemic Agents, and the Pharmacology of the Endocrine Pancreas". In Brunton L, Lazo J, Parker K. Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

- 1 2 Teale KF, Devine A, Stewart H, Harper NJ (July 1998). "The management of metformin overdose". Anaesthesia. 53 (7): 698–701. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.436-az0549.x. PMID 9771180.

- ↑ Spiller HA, Quadrani DA (May 2004). "Toxic effects from metformin exposure". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 38 (5): 776–80. doi:10.1345/aph.1D468. PMID 15031415.

- 1 2 Forrester MB (July 2008). "Adult metformin ingestions reported to Texas poison control centers, 2000-2006". Human & Experimental Toxicology. 27 (7): 575–83. doi:10.1177/0960327108090589. PMID 18829734.

- ↑ Gjedde S, Christiansen A, Pedersen SB, Rungby J (August 2003). "Survival following a metformin overdose of 63 g: a case report". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 93 (2): 98–9. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.930207.x. PMID 12899672.

- ↑ Nisse P, Mathieu-Nolf M, Deveaux M, Forceville X, Combes A (2003). "A fatal case of metformin poisoning". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 41 (7): 1035–6. doi:10.1081/CLT-120026533. PMID 14705855.

- 1 2 Suchard JR, Grotsky TA (August 2008). "Fatal metformin overdose presenting with progressive hyperglycemia". The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (3): 160–4. PMC 2672258. PMID 19561734.

- ↑ Spiller HA, Weber JA, Winter ML, Klein-Schwartz W, Hofman M, Gorman SE, Stork CM, Krenzelok EP (December 2000). "Multicenter case series of pediatric metformin ingestion". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 34 (12): 1385–8. doi:10.1345/aph.10116. PMID 11144693.

- 1 2 Calello DP, Liu KD, Wiegand TJ, Roberts DM, Lavergne V, Gosselin S, Hoffman RS, Nolin TD, Ghannoum M (August 2015). "Extracorporeal Treatment for Metformin Poisoning: Systematic Review and Recommendations From the Extracorporeal Treatments in Poisoning Workgroup". Critical Care Medicine. 43 (8): 1716–30. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001002. PMID 25860205.

- ↑ Liu A, Coleman SP (November 2009). "Determination of metformin in human plasma using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 877 (29): 3695–700. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.09.020. PMID 19783231.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 939–940.

- ↑ Somogyi A, Stockley C, Keal J, Rolan P, Bochner F (May 1987). "Reduction of metformin renal tubular secretion by cimetidine in man". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 23 (5): 545–51. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03090.x. PMC 1386190. PMID 3593625.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bristol-Myers Squibb (August 27, 2008). "Glucophage (metformin hydrochloride tablets) Label Information" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ↑ Jayasagar G, Krishna Kumar M, Chandrasekhar K, Madhusudan Rao C, Madhusudan Rao Y (2002). "Effect of cephalexin on the pharmacokinetics of metformin in healthy human volunteers". Drug Metabolism and Drug Interactions. 19 (1): 41–8. doi:10.1515/dmdi.2002.19.1.41. PMID 12222753.

- ↑ May M, Schindler C (April 2016). "Clinically and pharmacologically relevant interactions of antidiabetic drugs". Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 7 (2): 69–83. doi:10.1177/2042018816638050. PMC 4821002. PMID 27092232.

- ↑ Lord JM, Flight IH, Norman RJ (October 2003). "Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 327 (7421): 951–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7421.951. PMID 14576245.

- ↑ Hundal RS, Krssak M, Dufour S, Laurent D, Lebon V, Chandramouli V, Inzucchi SE, Schumann WC, Petersen KF, Landau BR, Shulman GI (December 2000). "Mechanism by which metformin reduces glucose production in type 2 diabetes". Diabetes. 49 (12): 2063–9. doi:10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2063. PMC 2995498. PMID 11118008.

- 1 2 3 Rena G, Pearson ER, Sakamoto K (September 2013). "Molecular mechanism of action of metformin: old or new insights?". Diabetologia. 56 (9): 1898–906. doi:10.1007/s00125-013-2991-0. PMC 3737434. PMID 23835523.

- 1 2 Burcelin R (May 2014). "The antidiabetic gutsy role of metformin uncovered?". Gut. 63 (5): 706–7. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305370. PMID 23840042.

- ↑ Madiraju AK, Erion DM, Rahimi Y, Zhang XM, Braddock DT, Albright RA, Prigaro BJ, Wood JL, Bhanot S, MacDonald MJ, Jurczak MJ, Camporez JP, Lee HY, Cline GW, Samuel VT, Kibbey RG, Shulman GI (June 2014). "Metformin suppresses gluconeogenesis by inhibiting mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase". Nature. 510 (7506): 542–6. Bibcode:2014Natur.510..542M. doi:10.1038/nature13270. PMC 4074244. PMID 24847880.

- ↑ Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, Musi N, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Moller DE (October 2001). "Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 108 (8): 1167–74. doi:10.1172/JCI13505. PMC 209533. PMID 11602624.

- ↑ Towler MC, Hardie DG (February 2007). "AMP-activated protein kinase in metabolic control and insulin signaling". Circulation Research. 100 (3): 328–41. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000256090.42690.05. PMID 17307971.

- ↑ Kim YD, Park KG, Lee YS, Park YY, Kim DK, Nedumaran B, Jang WG, Cho WJ, Ha J, Lee IK, Lee CH, Choi HS (February 2008). "Metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis through AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent regulation of the orphan nuclear receptor SHP". Diabetes. 57 (2): 306–14. doi:10.2337/db07-0381. PMID 17909097.

- ↑ Zhang L, He H, Balschi JA (July 2007). "Metformin and phenformin activate AMP-activated protein kinase in the heart by increasing cytosolic AMP concentration". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 293 (1): H457–66. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00002.2007. PMID 17369473.

- ↑ Miller RA, Chu Q, Xie J, Foretz M, Viollet B, Birnbaum MJ (February 2013). "Biguanides suppress hepatic glucagon signalling by decreasing production of cyclic AMP". Nature. 494 (7436): 256–60. Bibcode:2013Natur.494..256M. doi:10.1038/nature11808. PMC 3573218. PMID 23292513.

- ↑ Collier CA, Bruce CR, Smith AC, Lopaschuk G, Dyck DJ (July 2006). "Metformin counters the insulin-induced suppression of fatty acid oxidation and stimulation of triacylglycerol storage in rodent skeletal muscle". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 291 (1): E182–9. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00272.2005. PMID 16478780.

- ↑ Bailey CJ, Turner RC (February 1996). "Metformin". The New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (9): 574–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602293340906. PMID 8569826.

- ↑ Fantus IG, Brosseau R (October 1986). "Mechanism of action of metformin: insulin receptor and postreceptor effects in vitro and in vivo". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 63 (4): 898–905. doi:10.1210/jcem-63-4-898. PMID 3745404.

- ↑ Musi N, Hirshman MF, Nygren J, Svanfeldt M, Bavenholm P, Rooyackers O, Zhou G, Williamson JM, Ljunqvist O, Efendic S, Moller DE, Thorell A, Goodyear LJ (July 2002). "Metformin increases AMP-activated protein kinase activity in skeletal muscle of subjects with type 2 diabetes". Diabetes. 51 (7): 2074–81. doi:10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2074. PMID 12086935.

- ↑ Saeedi R, Parsons HL, Wambolt RB, Paulson K, Sharma V, Dyck JR, Brownsey RW, Allard MF (June 2008). "Metabolic actions of metformin in the heart can occur by AMPK-independent mechanisms". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 294 (6): H2497–506. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00873.2007. PMID 18375721.

- 1 2 Werner E, Bell J (1922). "The preparation of methylguanidine, and of ββ-dimethylguanidine by the interaction of dicyandiamide, and methylammonium and dimethylammonium chlorides respectively". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 121: 1790–95. doi:10.1039/CT9222101790.

- ↑ Shapiro SL, Parrino VA, Freedman L (1959). "Hypoglycemic Agents. I Chemical Properties of β-Phenethylbiguanide. A New Hypoglycemic Agent". J Am Chem Soc. 81 (9): 2220–25. doi:10.1021/ja01518a052.

- ↑ "Procédé de préparation de chlorhydrate de diméthylbiguanide". Patent FR 2322860 (in French). 1975.

- ↑ Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (Sittig's Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia). 3 (3rd ed.). Norwich, NY: William Andrew. 2007. p. 2208. ISBN 0-8155-1526-X.

- 1 2 Heller JB (2007). "Metformin overdose in dogs and cats" (PDF). Veterinary Medicine (April): 231–33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Rosilio C, Ben-Sahra I, Bost F, Peyron JF (May 2014). "Metformin: a metabolic disruptor and anti-diabetic drug to target human leukemia". Cancer Letters. 346 (2): 188–96. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.006. PMID 24462823.

- 1 2 Pryor R, Cabreiro F (November 2015). "Repurposing metformin: an old drug with new tricks in its binding pockets". The Biochemical Journal. 471 (3): 307–22. doi:10.1042/bj20150497. PMC 4613459. PMID 26475449.

- ↑ Graham GG, Punt J, Arora M, Day RO, Doogue MP, Duong JK, Furlong TJ, Greenfield JR, Greenup LC, Kirkpatrick CM, Ray JE, Timmins P, Williams KM (February 2011). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of metformin". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 50 (2): 81–98. doi:10.2165/11534750-000000000-00000. PMID 21241070.

- 1 2 Robert F, Fendri S, Hary L, Lacroix C, Andréjak M, Lalau JD (June 2003). "Kinetics of plasma and erythrocyte metformin after acute administration in healthy subjects". Diabetes & Metabolism. 29 (3): 279–83. doi:10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70037-x. PMID 12909816.

- ↑ Witters LA (October 2001). "The blooming of the French lilac". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 108 (8): 1105–7. doi:10.1172/JCI14178. PMC 209536. PMID 11602616.

- ↑ See Chemical Abstracts, v.23, 42772 (1929) Slotta KH, Tschesche R (1929). "Uber Biguanide. II. Die Blutzuckersenkende Wirkung der Biguanides". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft B: Abhandlungen. 62 (6): 1398–1405. doi:10.1002/cber.19290620605.

- 1 2 Campbell IW, ed. (2007). "Metformin – life begins at 50: A symposium held on the occasion of the 43rd Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, September 2007". The British Journal of Diabetes & Vascular Disease. 7 (5): 247–52. doi:10.1177/14746514070070051001.

- ↑ Dawes GS, Mott JC (March 1950). "Circulatory and respiratory reflexes caused by aromatic guanidines". British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 5 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1950.tb00578.x. PMC 1509951. PMID 15405470.

- ↑ About Eusebio Y. Garcia, see: Carteciano J (2005). "Search for DOST-NRCP Dr. Eusebio Y. Garcia Award". Philippines Department of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 2009-10-24. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ Quoted from Chemical Abstracts, v.45, 24828 (1951) Garcia EY (1950). "Fluamine, a new synthetic analgesic and antiflu drug". J Philippine Med Assoc. 26: 287–93.

- ↑ About Janusz Supniewski, see: Wołkow PP, Korbut R (April 2006). "Pharmacology at the Jagiellonian University in Kracow, short review of contribution to global science and cardiovascular research through 400 years of history" (pdf). Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 57 Suppl 1: 119–36. PMID 16766803. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-10-24.

- ↑ See Chemical Abstracts, v. 52, 22272 (1958) Supniewski J, Chrusciel T (1954). "[N-dimethyl-di-guanide and its biological properties]". Archivum Immunologiae Et Therapiae Experimentalis (in Polish). 2: 1–15. PMID 13269290.

- ↑ Quoted from Chemical Abstracts, v.49, 74699 (1955) Supniewski J, Krupinska J (1954). "[Effect of biguanide derivatives on experimental cowpox in rabbits]". Bulletin de l'Academie Polonaise des Sciences, Classe 3: Mathematique, Astronomie, Physique, Chimie, Geologie et Geographie (in French). 2(Classe II): 161–65.

- 1 2 3 Bailey CJ, Day C (2004). "Metformin: its botanical background". Practical Diabetes International. 21 (3): 115–17. doi:10.1002/pdi.606.

- ↑ Hadden DR (October 2005). "Goat's rue - French lilac - Italian fitch - Spanish sainfoin: gallega officinalis and metformin: the Edinburgh connection" (PDF). The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 35 (3): 258–60. PMID 16402501.

- ↑ Lucis OJ (January 1983). "The status of metformin in Canada". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 128 (1): 24–6. PMC 1874707. PMID 6847752.

- ↑ Cruzan SM (December 30, 1994). "FDA Approves New Diabetes Drug" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Glucophage Label and Approval History. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved January 8, 2007. Data available for download on FDA website Archived 2009-08-14 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "Metformin". rxwiki. 9 July 2012. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013.

- ↑ Bailey CJ, Day C (June 2009). "Fixed-dose single tablet antidiabetic combinations". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 11 (6): 527–33. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00993.x. PMID 19175373.

- ↑ "FDA Approves GlaxoSmithKline's Avandamet (rosiglitazone maleate and metformin HCl), The Latest Advancement in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes" (Press release). GlaxoSmithKline. October 12, 2002. Archived from the original on January 21, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ↑ "2009 Top 200 branded drugs by total prescriptions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-14. (96.5 KB). Drug Topics (June 17, 2010). Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers about the Seizure of Paxil CR and Avandamet" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 4, 2005. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ↑ "Teva Pharm announces settlement of generic Avandia, Avandamet, and Avandaryl litigation with GlaxoSmithKline" (Press release). Reuters. September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ↑ Nissen SE, Wolski K (June 2007). "Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (24): 2457–71. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072761. PMID 17517853.

- ↑ "European Medicines Agency recommends suspension of Avandia, Avandamet and Avaglim". News and Events. European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ↑ "Call to 'suspend' diabetes drug". BBC News. 2010-09-23. Archived from the original on 2010-09-24.

- ↑ "Drugs banned in India". Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Dte.GHS, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- ↑ "Diabetes drug withdrawn". Stuff.co.nz. NZPA. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ Harris G (February 19, 2010). "Controversial Diabetes Drug Harms Heart, U.S. Concludes". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Most Popular E-mail Newsletter". USA Today. 2011-05-24.

- ↑ "Glaxo's Avandia Cleared From Sales Restrictions by FDA". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2014-11-09.

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (November 25, 2013). "FDA requires removal of certain restrictions on the diabetes drug Avandia". Archived from the original on May 4, 2015.

- ↑ "US agency reverses stance on controversial diabetes drug". Archived from the original on 2015-12-11.

- ↑ "European Medicines Agency – Human medicines – CHMP summary of positive opinion for Pioglitazone ratiopharm". Archived from the original on 2015-12-11.

- ↑ "Safety Information – Actoplus Met (pioglitazone and metformin) fixed-dose combination tablets". Archived from the original on 2015-12-11.

- ↑ Jentadueto Archived 2012-07-23 at the Wayback Machine. at the European Medicines Agency. First published 25/05/2012

- ↑ ""The Use of Medicines in the United States: Review of 2010"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-04-22. (1.79 MB). IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics (April 2011). Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ↑ Panikar V, Chandalia HB, Joshi SR, Fafadia A, Santvana C (November 2003). "Beneficial effects of triple drug combination of pioglitazone with glibenclamide and metformin in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients on insulin therapy". The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 51: 1061–4. PMID 15260389.

- ↑ Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, Tomassetti S, Zoli M, Melchionda N (September 2001). "Metformin in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis". Lancet. 358 (9285): 893–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06042-1. PMID 11567710.

- ↑ Socha P, Horvath A, Vajro P, Dziechciarz P, Dhawan A, Szajewska H (May 2009). "Pharmacological interventions for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults and in children: a systematic review". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 48 (5): 587–96. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818e04d1. PMID 19412008.

- 1 2 Angelico F, Burattin M, Alessandri C, Del Ben M, Lirussi F (January 2007). "Drugs improving insulin resistance for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and/or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 24 (1): CD005166. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005166.pub2. PMID 17253544.

- ↑ Ibáñez L, Ong K, Valls C, Marcos MV, Dunger DB, de Zegher F (August 2006). "Metformin treatment to prevent early puberty in girls with precocious pubarche". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 91 (8): 2888–91. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0336. PMID 16684823.

- ↑ Ben Sahra I, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF, Bost F (May 2010). "Metformin in cancer therapy: a new perspective for an old antidiabetic drug?". Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 9 (5): 1092–9. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1186. PMID 20442309.

- ↑ Malek M, Aghili R, Emami Z, Khamseh ME (September 2013). "Risk of cancer in diabetes: the effect of metformin". ISRN Endocrinology. 2013: 636927. doi:10.1155/2013/636927. PMC 3800579. PMID 24224094.

- 1 2 Campbell JM, Bellman SM, Stephenson MD, Lisy K (November 2017). "Metformin reduces all-cause mortality and diseases of ageing independent of its effect on diabetes control: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Ageing Research Reviews. 40: 31–44. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2017.08.003. PMID 28802803.

- ↑ Barzilai, Nir; Crandall, Jill P.; Kritchevsky, Stephen B.; Espeland, Mark A. (June 2016). "Metformin as a Tool to Target Aging". Cell Metabolism. 23 (6): 1060–1065. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metformin. |

- Metformin at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Metformin