Senjak

| Senjak Сењак | |

|---|---|

| Urban neighbourhood | |

|

BIGZ building | |

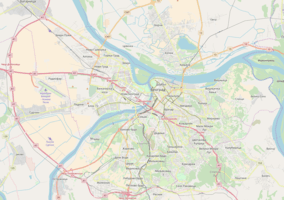

Senjak Location within Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°47′32″N 20°26′19″E / 44.792328°N 20.438669°ECoordinates: 44°47′32″N 20°26′19″E / 44.792328°N 20.438669°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Belgrade |

| Municipality | Savski Venac |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.18 km2 (1.23 sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

Senjak (Serbian: Сењак; pronounced [sêɲaːk]) is an urban neighborhood of Belgrade, the capital city of Serbia. Located in Savski Venac, one of the three municipalities that constitute the very center of the city, it is an affluent and distinguished neighborhood lavished with embassies, diplomatic residences, and mansions. Senjak is generally considered one of the wealthiest parts of Belgrade.

History and etymology

Before it became interesting to Belgrade's upper classes, Senjak was an excellent natural lookout. As many farmers kept their hay throughout the entire city, fires were quite frequent, so it was ordered for hay to be collected and kept in one place, and the area of modern Senjak was chosen, apparently also getting its name in the process (from the word seno, Serbian for hay). A more romantic theory of the neighborhood's name (from the word sena, Serbian for 'shade' or 'shadow') confronts the former theory.

During the 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia, a number of buildings in the neighborhood such as the Swiss ambassador's residence were damaged or affected by the conflict.

The first tram link established in Belgrade was from the Kalemegdan fortress to Senjak.

Geography

Senjak is located 3 km south-west of downtown Belgrade, on top of the hilly cliff-like crest of the western slopes of Topčidersko Brdo, overlooking Belgrade Fair right below and the Sava river (from which, at the closest point, Senjak is only 100 meters away). It borders the neighborhoods of Topčider and Careva Ćuprija (south), Mostar (north), Prokop and Dedinje (east). The triangularly shaped neighborhood has many smaller streets but it is bounded by two wide boulevards, named after Serbian army vojvodas from World War I: Vojvoda Mišić and Vojvoda Putnik.

Administration

Senjak originally belonged to the former municipality of Topčidersko Brdo, which in 1957 merged with the municipality of Zapadni Vračar to create the municipality of Savski Venac. Senjak existed as the local community within Savski Venac with the population of 3,690 in 1981.[1] It was later merged into the new local community of Topčidersko Brdo-Senjak which had a population of 7,757 in 1991,[2] 7,249 in 2002[3] and 6,344 in 2011.[4]

Characteristics

Just like the neighboring Dedinje, Senjak is generally considered among Belgraders as one of the richest neighborhoods in the city. After 1945, it shared much of the same fate as Dedinje: when Communists took over, they declared almost all former residents as state enemies and forced them out of their mansions, so the new Communist political and military elite moved in. Some measures in removing the former high class were brutal as only those who fled the country stayed alive. Those unlucky were taken into a nearby woods and shot, with their remains lying in unmarked graves for decades until they were exposed by construction workers clearing trees for a new soccer field.

Bulevar vojvode Mišića, encircles Senjak from the north, west and south and separates it from the Belgrade Fair, Careva Ćuprija and Topčider. As of 2017, it was the street with the busiest traffic in Belgrade: 8,000 vehicles per hour in one direction during the morning rush hour.[5]

Features

Buildings

King Peter's House

A vacant summer house of King Peter I Karađorđević. The house stands across the soccer field of "FK Grafičar" and close to the building of the military academy. The house, called the "White villa", was built in 1896 and it belonged to the merchant Živko Pavlović. In 1919 the state, represented by the Ministry of education, leased the house for the king who lived there from 1919 to his death in 1921.[6] Monthly rent was 3,000 dinars in silver. The king lived quite modestly. His own room was equipped with bed, small cabinet with the sink, locker, lamp, sable and chandelier. The king had his own library, with the books printed by the Srpska književna zadruga. He spent lots of time on the vast terrace and in the garden. After king's death in August 1921, the Royal Intendancy bought the house out in order to make it a museum. In 1930s it was declared a king's memorial-house. [7]

After 1945 residents changed and mostly included the high ranking members of the new Communist elite and in that period majority of the exhibited artifacts, the legacy of the king, were either destroyed od taken away.[8] Missing items include the king's death mask and the only remaining artifact was the king's bed. In 1945 the house was adapted into the elementary school which was closed in 1951 and the house, for the most part since then, remained abandoned and left to the elements. In 2010 the house was adapted into the cultural center. Within the house, a memorial room for the king was set, which includes a mosaic of 100 photographs of the king and his family.[7]

In the house's yard, there are two trees, protected by the law since 1998. One is a 20 meters high gingko and the other is a 10 meters high magnolia tree. As of 2017, both trees are estimated at being 110 years old.[9]

Other buildings

- Military Academy; after World War I, military academy was constructed by orders of King Peter I. The academy's building is majestic, with heavy cream-colored walls and tall windows. During World War II the occupational German forces made it the headquarters for their military operations in the Balkans. The Allies bombed the neighborhood during the war in order to destroy the headquarters and the bridge over the Sava, but they didn't manage to hit it or cause any damage to the building or the bridge.

- Museum of African Art; it was established from the private collection of a Yugoslav diplomat, and contains many rare pieces.

- Museum of Toma Rosandić; located in the house, where the famous sculptor lived and worked until his death, was built by himself in 1929, and now holds a unique collection that is, unfortunately, not open to public, except on certain days (such as The Museum Night).

- Ecole Française de Belgrade, an international French school founded in 1951. The school is composed of a nursery school, an elementary school, a middle school and a high school.

- Senjak Gymnastics Club, which was a starting point for the future career of the renowned Yugoslav rhythmic gymnast Milena Reljin.

- The Archives of Yugoslavia and stadium and restaurant "FK Grafičar", both in the vicinity of Topčiderska zvezda, small roundabout with streets spreading in all directions connecting Senjak, Dedinje, downtown Belgrade, Topčider and further to the south (Kanarevo Brdo, Rakovica, etc.).

- BIGZ building

- Faculty of Economics, Finance and Administration (member of Singidunum University)

- International School of Belgrade

- Old Mill, a cultural monument since 1987, in 2014 adapted into the Radisson Blu Old Mill Hotel.

- Senjak Greenmarket (Senjačka pijaca) was located along the Sava river and was originally built for the workers of the Cardboard factory of Milan Vapa, which was right across it. The factory complex included the apartments for workers. Market is still operational, albeit smaller, along the Koste Glavinića Street.[10]

Nature

- Two state protected trees of the Himalayan white pine, native to Afghanistan and Himalaya. They were planted in 1929, in the yard of the family of the famous scientist Milutin Milanković, in the Žanke Stokić street.[11]

- Protected natural monument "Dedinje Beech", a European beech tree, noted for its unusually big size in urban habitats: 22 meters tall, 2,8 meter trunk diameter, 19 meters crown diameter. As of 2017 it is estimated at being 90 years old.[9]

Sub-neighborhoods

Gospodarska Mehana

Gospodarska Mehana (Serbian: Господарска Механа) is the westernmost section of Senjak. It occupies the slopes descending to the Sava, just across the southern end of the Belgrade Fair and north of the Topčiderka's mouth into the Sava. It was named after the famed, and one of the longest surviving kafana in Belgrade, Gospodarska mehana. Kafana was founded in 1820 in what was at the time the end of the city. [12] Due to the construction of the Ada Bridge, access roads to it and an loop interchange, the kafana was cut off and had to be closed in September 2013, after 193 years.[13]

In 1821, the state government decided to put the food trade in order and to establish the quantity and quality of the goods imported to the city. Part of the project was introduction of the excise on the goods (in Serbian called trošarina) and setting of a series of excise check points on the roads leading to the city.[14] One of those check points, which all gradually also became known as trošarina, was located here as in 1830s and 1840s it was a location of the ferry which transported pigs across the Sava into the Austria. This trošarina also functioned as a customs house. In 1859 when prince Miloš Obrenović and his son Mihailo Obrenović returned to Serbia, they landed at Gospodarska Mehana.[15] It was the final stop of the first Belgrade's tram line and still is on the important traffic route with important streets (Boulevard of Vojvoda Mišić, Radnička Street), railway, public transportation lines (still surviving tram line), road elevation which connects Banovo Brdo and Čukarica with Belgrade (formerly known as the "Gospodarska Mehana elevation"), etc. In 1930s, when most of Belgrade's upper class built houses in Dedinje, some decided to build houses in Gospodarska Mehana, including then Prime minister of Yugoslavia, Milan Stojadinović.

The bank of the Sava river at Gospodarska Mehana was the most popular Belgrade's beach during the Interbellum. The beach was known as the "Šest Topola" ("Six Poplars") and especially boomed after 1933 when other beaches were closed.[16] After World War II, neighboring Ada Ciganlija became the top excursion site. The name of "Šest Topola" is preserved in the name of the restaurant on the Sava's bank near the Belgrade Fair.

Slope right above the Gospodarska Mehana is called Rajsova padina (Reiss’ Slope), named after Archibald Reiss, Swiss forensics pioneer who lived in Senjak after moving to Serbia when the World War I ended. In May 2011, as part of the project of foresting the city and creating a green barrier against traffic from the interchange and the roads, 400 trees were planted on Rajsova padina, including cedar, pedunculate oak, Cypress oak and Siberian elm.[17]

Mostar Interchange

Smutekovac

In the mid-19th century, northern part of modern Senjak was a meadow, with only the Topčider road passing through. It was used as the training ground for the army and as the pasture for the sheep. Czech émigré Smutek, who owned a kafana, arranged a large estate and a beautiful garden in the area, which then became known as Smutekovac. It became a popular excursion site for the Belgraders, which originally came by fiacres and later by the tram "Topčiderac", which connected the downtown with Topčider. In the 1870s the area was parceled and Đorđe Vajfert purchased the land from the lawyer Pera Marković. As he was a German subject, he couldn't own properties in Serbia. Instead he paid the entire sum to Marković who issued him a receipt. Vajfert then started to build the brewery, predecessor of the modern BIP brewery at the same location. As soon as he was granted Serbian citizenship, Vajfert received a deed on the land. He finished the brewery and turned the surrounding estate into an exquisite garden, which hosted many banquets and parties. In 1892, city authorities organized a banquet with Nikola Tesla as the guest of honor.[18][19]

References

- ↑ Osnovni skupovi stanovništva u zemlji – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1981, tabela 191. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Stanovništvo prema migracionim obeležjima – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1991, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva po mesnim zajednicama, Saopštenje 40/2002, page 4. Zavod za informatiku i statistiku grada Beograda. 26 July 2002.

- ↑ Stanovništvo po opštinama i mesnim zajednicama, Popis 2011. Grad Beograd – Sektor statistike (xls file). 23 April 2015.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (5 December 2017), "Beograd i dalje čeka metro" [Belgrade still awaits the subway], Politika (in Serbian), p. 15

- ↑ M.Simić (8 July 2009), "Oživljavanje Bele vile na Senjaku", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 Liljana Petrović (interview with Nevena Milić) (21–27 July 2018). "Благо је свуда око нас" [Treasure is all around us]. TV Revija (in Serbian). pp. 06–07.

- ↑ M.Simić (9 July 2009), "Remek-dela i hiphop u kući kralja Petra Prvog", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 Branka Vasiljević (15–16 April 2017). "Stogodišja stable na Dedinju i Senjaku" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 26-27.

- ↑ Dragan Perić (22 October 2017), "Beogradski vremeplov - Pijace: mesto gde grad hrani selo" [Belgrade chronicles - greenmarkets: a place where village feeds the city], Politika-Magazin, No. 1047 (in Serbian), pp. 26–27

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (26 April 2008), "Vekovi u krošnjama", Politika (in Serbian), p. 32

- ↑ Gospodarska mehana

- ↑ M.T.Kovačević (17 September 2013). "Beograd: katanac na Gospodarsku mehanu" (in Serbian). Večernje novosti.

- ↑ Dragan Perić (22 October 2017), "Beogradski vremeplov - Pijace: mesto gde grad hrani selo" [Belgrade chronicles - Greenmarkets: a place where village feeds the city], Politika-Magazin, No. 1047 (in Serbian), pp. 26–27

- ↑ Gospodarska mehana

- ↑ "Na levoj Savi nema vise kupača", Politika (in Serbian), 1933

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (6 May 2011), "Novih 100 sadnica na Rajsovoj padini", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ "Iz starog Beograda - Bulevar vojvode Putnika", Politika (in Serbian), 4 June 1967

- ↑ Bojan Kovačević (April 2014), "Lica grada", Politika (in Serbian)

External links

- Official website of Savski Venac, the municipality in which Senjak resides (in Serbian)

- Photo gallery of Senjak

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Senjak. |