Terazije

| Terazije | |

|---|---|

| City square | |

| |

| Opening date | early 19th century |

| Owner | City of Belgrade |

| Location | Belgrade, Serbia |

Terazije | |

| Coordinates: 44°48′49″N 20°27′40″E / 44.81361°N 20.46111°ECoordinates: 44°48′49″N 20°27′40″E / 44.81361°N 20.46111°E | |

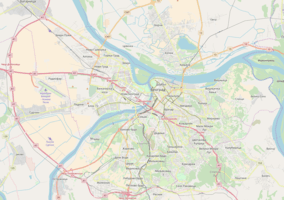

Terazije (Serbian: Теразијe) is the central town square and the surrounding neighborhood of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is located in the municipality of Stari Grad.

Location

Despite the fact that many Belgraders consider the Republic Square or Kalemegdan to be the city's centerpiece areas, Terazije is Belgrade's designated center. When street numbers are assigned to the streets of Belgrade, numeration begins from the part of the street closest to Terazije. Terazije itself is also a short street, connected by the King Milan Street, the main street in Belgrade, to the Slavija square, by the Nikola Pašić Square to the King Alexander Boulevard, the longest street in Belgrade, by Prizrenska street to the neighborhood of Zeleni Venac and further to Novi Beograd, and by the Kolarčeva street to the Square of the Republic.

Etymology

Terazije literally means scales, more commonly known as "water balances" or "su terazisi" in Turkish. The meaning of Turkish word "su terazisi" needs to be explained fully because the English term "scales" does not seem to be adequate. Terazije is probably more related to the word "reservoir" connected to the ancient Roman aqueduct which existed before the Ottoman times. Perhaps Terazije is connected to a water distribution mechanism which existed here which lifted and distributed water further into the city. There is an underground natural and/or man made underground river in this area. "Water Balances" known as "su terazisi", were tower-like structures maintaining water pressure when conveying water to neighbourhoods at a high-level. Varying from 3 to 10 m in height, they had a cistern at the summit from which the water flowed into distribution pipes.

History

Before 1900

Terazije started to take shape as an urban feature in the first half of the 19th century. In the 1840s, Prince Miloš Obrenović ordered Serbian craftsmen, especially blacksmiths and coppersmiths, to move out of the old moated town where they had been mixed with the Turkish inhabitants, and build their houses and shops on the place of the present square. Also, the move was intended to prevent the fires being lit all over the town. Ilija Čarapić, the president of the Belgrade Municipality 1834-35 and 1839–40, had a special task to assigning lots of land at Terazije to these craftsmen and whoever accepted to fence the lot, would have it for free.

With regard to the origin of the name Terazije, the historian and writer Milan Đ. Milićević noted that "In order to supply Belgrade with water, the Turks built towers at intervals along the water supply system which brought water in from the springs at Veliki Mokri Lug. The water was piped up into the towers for the purpose of increasing the pressure, in order to carry it further." One such tower was erected on the location of the present fountain at Terazije and the square was named after the Turkish word for water tower, terazi (literally, water scales).

In the mid-19the century, Atanasije Nikolić, educator and agriculturist, planted a number of chestnut trees on Terazije.[1] Up to about 1865, the buildings at Terazije were mainly single and double-storied. The water tower was removed in 1860 and replaced by the drinking fountain, "Terazijska česma", which was erected in to celebrate the second rule of Prince Miloš Obrenović. During the first reconstruction of the square in 1911, the "česma" was moved to Topčider.

1900-1941

In the summer of 1911 a plan for the arrangement of Terazije was developed, headed by the special commission constituted specifically for this purpose and headed by architect Édouard Léger. Most of the provisions envisioned by the project were built: new wide paved sidewalks, formation of the square, a fountain, change in tram tracks for better and faster traffic and removal of the public pissoirs. A monument to Dositej Obradović, which was projected, was erected in a different neighborhood.[2] The changes in 1911-1913 were significant and the square was completely re-arranged. With Léger, major work was done by the architects Veselin Lučić and Jelisaveta Načić. Along the central part of the square regular flower beds were placed,surrounded by a low iron fence. Refurbishment included artistic candelabra, public three-faced clock, a special kiosk in the Serbian-Byzantine style, circle bars for the protection of the trees in the avenue and granite curbs. On the side towards today's Nušićeva street a large Terazije fountain was built in 1927.[1][3] At the end of the XIX and beginning of the 20th century, Terazije was the centre of social life of Belgrade.[4]

In 1913, the city administration headed by Ljubomir Davidović, decided to change the name of the square into the Prestolonaslednikov trg ("Heir's apparent square"), referring to prince Alexander, future king Alexander I of Yugoslavia. Another decision was to build the fountain on the square which would include the monument to victory. The ideas came after the Balkan Wars and were triggered by the ceremonial entry of the Serbian army in Belgrade after the war ended, and the construction of the Karađorđe monument in Kalemegdan. Due to the World War I which ensued shorty after, the decisions weren't fully implemented: the name wasn't change, the monument was relocated to the Belgrade Fortress, while the short-lived fountain was ultimately built.[5] Curiously, despite being the sole center of the city, some areas evaded urbanization until the late 1930s, like the Kuzmanović Yard.[6]

World War II

In order to "effectively intimidate the population" and discourage the people from fighting the occupiers, a military commander of Serbia Heinrich Danckelmann and the head of the Belgrade Gestapo Carl Krauss ordered a killing of five Serbs on Terazije. The executed victims were Velimir Jovanović (b.1893) and Ratko Jević (b. 1913), farmers, Svetislav Milin (b. 1915), a shoemaker, Jovan Janković (b.1920), a tailor, and Milorad Pokrajac (b. 1924), a high school student, only 17 years old.[7] They were arrested, accused of alleged terrorist activities and brutally tortured before being shot in the yard of the Gestapo headquarters. The entire ordeal happened on 17 August 1941. Their corpses were then hanged on the light poles on Terazije, where they remained for days. A monument to commemorate the crime was erected in 1981 by the city. Titled "Monument to the hanged patriots" and sculptured by Nikola Janković, the obelisk shaped monument is 4 m (13 ft) tall with a diameter of 80 cm (31 in). It is posted on the marble pedestal and has carvings representing the scenes of the hanging and a commemorative lyrics by the poet Vasko Popa. In 1983 a memorial bronze plaque, work of Slave Ajtoski, was added. It contains names of the victims and an epitaph: "To freedom fighters who were hanged by the Fascist occupiers in Terazije on 17 August 1941", signed by "citizens of Belgrade". The plaque got damaged in time and was removed in 2008, during the reconstruction of Terazije, for restoration. It was returned on 28 May 2011.[8][9]

The square and the Palace Albania were hit during the heavy "Easter bombing" of Belgrade by the Allies on 16 April 1944.[10]

After 1945

Modern appearance of Terazije is mostly set after 1947. City's main urbanist, Nikola Dobrović, in order to adapt to square for the May 1st military parade, demolished almost everything on the ground level, including all of the flower beds and the other urban ornamentals, so as the fountain[3] and after 1948 the main square in Belgrade was narrowed, double tram tracks from both sides were removed and a number of modernist buildings were constructed, forming a Square of Marx and Engels (present Square of Nikola Pašić) in the 1950s to the north. Terazije became a "lifeless" ground for the parade and, in the future, for the automobile traffic.[3]

In 1958, the sculptural group by Lojze Dolinar, which represented merchant Sima Igumanov and two orphans, was removed from the roof of Igumanov's bequest, the Iguman's Palace, to make way for the first neon commercial signage.Aa mobile advertisement for the Zagreb's Chromos Corporation, it was the first neon commercial sign in Belgrade.[11]

Terazije Tunnel was opened in 1970 and in 1976 the old "Terazijska česma" was returned from Topčider back to the square and placed at its present location.

Administration

Terazije quarter had a population of 6,333 by the 1883 census of population.[12] According to the further censuses, the population of Terazije was 5,273 in 1890, 6,074 in 1895, 6,494 in 1900, 6,260 in 1905, 9,049 in 1910 and 7,038 in 1921.[13][14]

For a short period after the World War II, when Belgrade was administratively reorganized from districts (raions) into the municipalities in 1952, Terazije had its own municipality with the population of 17,858 in 1953.[15] However, already on 1 January 1957 the municipality was dissolved and divided between the municipalities of Vračar and Stari Grad. Population of the modern local community (mesna zajednica) of Terazije was 5,033 in 1981,[16] 4,373 in 1991[17] and 3,338 in 2002.[18] Municipality of Stari Grad later abolished the local communities so data from the 2011 census are not known.

Notable buildings

As the central and one of the most famous squares in Belgrade, it is the location of many famous Belgrade buildings. The most important hotels, restaurants and shops are or were located here.

Former

- Hotel Pariz; it was built in 1870 at the spot where Bezistan passage and shopping area is located today. Hotel was demolished during the reconstruction of the square in 1948;[19]

- Kod zlatnog krsta (Serbian for 'By the Golden Cross'); a kafana where the first film was shown by the Lumière brothers on 6 June 1896; used to be at the spot where Dušanov grad is located today;

- Takovo restaurant and cinema;

Present

- Hotel Kasina; the old hotel was built around 1860, next to Hotel Pariz. The owner of Kasina was Doka Bogdanović (1860-1914). He allowed for the travelling cinemas to show movies in Kasina in the 1900s and in 1910 Jovanović opened the permanent cinema. In 1913 he founded the "Factory for the making of the cinematography films" and purchased the technology for filming movies. He hired Russian photographer Samson Chernov who filmed photo journals from the Second Balkan War which Jovanović showed in Kasina under the title "First Serbian program". When the World War I broke out, Jovanović and Chernov were filming new movies for the cinema in September 1914 on the Syrmian front, when Jovanović fell off the horse, dying after a while from the aftermaths of the fall.[20] At this hotel, in 1918 the National Assembly of Serbia held its meetings for a while. The plays of the National Theatre in Belgrade have been performed here until 1920. The present Hotel Kasina was built at the same place in 1922;

- Hotel Balkan; right across the Hotel Moskva; originally a one-story building built in 1860, which was demolished in 1935 when the present building of the hotel was constructed, work of architect Aleksandar Janković;[19] The old building was also known as the Simina mehana ("Sima's meyhane") and was the gathering point for the volunteers during the Serbian-Turkish wars;[21] Singer Zdravko Čolić recorded a song about the hotel in 2000;[19][22]

- Hotel Moskva; built in 1906; still preserving the original shape with its famous façade made of ceramic tiles. Often voted as one of the most beautiful buildings in Belgrade;

- Palace Albania, built in 1937, the first high rise in Belgrade and the highest building in the Balkans before World War II;

- The biggest McDonald's restaurant in the Balkans;

- Theatre on Terazije, the Serbian equivalent to Broadway staging numerous musical productions and adaptations from around the world. The theatre is one of the most modern in Belgrade being reconstructed in 2005;

Other features

Bezistan

Bezistan is a shopping area in an indoor passage which connects Terazije and the Square of Nikola Pašić. Originally, it was a location of Hotel "Pariz", which was built in 1870 and demolished in 1948 during the reconstruction of Terazije. Passage has been protected by the state as a "cultural property", though still under the "preliminary protection", and was nicknamed by the architects as the "belly button of Belgrade".[23] It is part of the wider protected Spatial Cultural-Historical Unit of Stari Grad.[24]

Since the 1950s, the covered square was a quiet corner in sole downtown, with mini gardens and coffee shops and a popular destination of many Belgraders, but in the recent decades mainly lost that function. In 1959 a round plateau with the fountain and a bronze sculpture, called “Girl with the seashell”, sculptured by Aleksandar Zarin, was built. A webbed roof, shaped like a semi-opened dome, made of concrete and projected by Vladeta Maksimović, was constructed to cover the plateau and the fountain. Because of that feature, and a small shops located in it, it was named "Bezistan", though it never functioned as the bezistan in its true, oriental sense of the term. Revitalization and reconstruction was projected for the second half of 2008, but the only work that has been done was the reconstruction of the plateau and the fountain in 2011.[24][25]

Bezistan covers an area of 13,667 m2 (147,110 sq ft).[25] The major feature within Bezistan was the "Kozara" cinema, one of the most popular in Belgrade for decades. It was closed in 2003, purchased by Croatian tycoon Ivica Todorić and allegedly planned as a supermarket for Todorić's Serbian brand "Idea" before it was destroyed by fire on 25 May 2012[26][27] It has been left in that condition ever since. Bezistan had candy and souvenir shops on one side, and modernistic section on other side, with McDonald's restaurant, modern coffee shop and "Reiffeisen bank", but as of 2018 it looks like nothing more than a neglected, empty passage. New possible reconstruction was announced in April 2017,[25] followed by a series of postponing: for October 2017, January, March and May 2018. The project includes new paving of the area and reintroduction of the greenery.[24]

Čumić Alley

In the early 20th century, a section behind the main square became a hub of commercial and craft shops. After the owner of the lot, quite big for the central urban zone of the city, Živko Kuzmanović, the area became known as the Kuzmanović Alley, or Kuzmanović Yard. Initially quite a successful business area, by the 1930s the shops went bankrupt and were closed. The alley was transformed into an informal settlement.[28] In the reprint of its article from 13 March 1937, daily Politika writes about the city’s decision to tear down the Kuzmanović Yard: It seems that another disgrace will disappear from Belgrade, but much larger and more dangerous for the health and lives of the people than that eyesore that ”Albania” was. A row of shacks and hovels in ”Kuzmanović yard”, which altogether cover an area of 4.000 m2 between the streets of Dečanska, Pašićeva nad Kolarčeva, will disappear. Belgrade municipality sent its commission yesterday to check the condition of the ”Kuzmanović yard”. The commission established that the shanties and burrows are prone to collapse any minute and that it will advocate for them to be teared down, in the interest of health and lives of the tennants.[6] The shantytown was demolished by 1940. The alley was later renamed Čumićevo Sokače ("Čumić Alley") after a politician Aćim Čumić, former mayor of Belgrade and prime minister of Serbia.[28]

In 1989, the first modern shopping mall (concurrently with the Staklenac on the Republic Square) in Belgrade was opened in Čumić Alley, colloquially shortened only to Čumić. It soon became one of the elite shopping locations in Belgrade, with numerous cafés, galleries and clubs in addition. It is also the shortest passage between the squares of the Republic and of Nikola Pašić. By the late 1990s, when other shopping malls started to open around the city, the decline of Čumić began. By 2010, the district was almost completely abandoned, becoming a ghost town. Then a group of young designers moved into the empty shops and began selling their homemade crafts, forming a Belgrade Design District with over 100 shops. In 2018 city administration stepped in with plans of creating a full artistic quart in the future.[28]

Sremska

Sremska is a short, curved street which connects the section where the Knez Mihailova and Terazije meet and the Maršala Birjuzova street, making a pedestrian connection between Terazije and Zeleni Venac, and with Varoš Kapija, further down the Maršala Birjuzova. Sremska is known for the shopping mall on its right side. On the left side, the tall building of "Agrobanka" was built from 1989 to 1994, and as a part of the project, a barren concrete plateau was built right above the Terazije tunnel. Since 1990s it was used as a location for the small flea market. In 2005 the market was removed and from December 2010 to April 2011 the concrete slab was turned into a mini-square (piazzetta) with small, mobile park, in the form of the roof garden. The urban pocket has lawns, flowers and evergreen shrubs. It is also Belgrade's first public location in the past 100 years that had a mosaic done on the floor. Materials used include the porous concrete, movable metal construction on which the grass turfs are planted and the drip irrigation system was installed. With Terazije, it is part of the "Stari Beograd" ("Old Belgrade") cultural unit, which is under protection.[29][30]

Terazije Fountain

In history, there were 2 fountains in Terazije: a drinking fountain (1860-1911 & 1976-) and a fountain (1927-47).

Terazije drinking fountain (Serbian: Теразијска чесма, Terazijska česma);

In 1860 the old water tower was removed and replaced with the drinking fountain. It was built to celebrate the return of Prince Miloš Obrenović to Serbia and his second rule.[31] During the reconstruction of Terazije, the fountain was moved to Topčider in 1911. It was situated in the churchyard of the Topčider Church.[32] It was reinstated in Terazije in 1976, in front of the Moskva Hotel.

Terazije fountain (Serbian: Теразијска фонтана, Terazijska fontana);

The first proper, decorative fountain (fontana) in Belgrade, as previously only drinking fountains (česma) were built.[31]

A plan for the rearrangement of Terazije in the summer of 1911, among numerous other changes, included the construction of a new fountain.[2] Among many rundelas (round flower beds), on the side towards today's passage to the Nušićeva street one rundela was used as the base for the postament of the monument “Victory Herald”, a work of Ivan Meštrović. Meštrović’s statue was finished in 1913,[33] immediately after and as a continuation, in concept and style, of the cycle of sculptures intended for his large-scale project for a shrine commemorating the Battle of Kosovo ("Temple of Vidovdan"), which includes representative sculptures such as Miloš Obilić and Marko Kraljević. Conceived as a colossal athletic male nude set up on a tall column, the monument symbolically represents the iconic figure of victory. In iconographic terms, the personification of the triumph of a victorious nation can be traced back to classical antiquity and its mythic hero Hercules.[33] The outbreak of World War I and the reconstruction of a massively demolished Belgrade delayed the dedication but the idea was revived in the 1920s. However, some puritan and female organizations protested heavily against posting a 5 m (16 ft) tall figure of a fully naked man in downtown. It was then opted to erect the monument in the Kalemegdan Park in the Belgrade Fortress. Becoming known as Pobednik (The Victor), the statue is today a symbol and one of the most recognized landmarks of Belgrade.[34]

The rundela designated as the base of the monument remained empty. Due to the impending marriage of the King Alexander I Karađorđević and Romanian princess Maria, city architect Momir Korunović was given a task of making something out of it, worthy of the royal wedding which was set for 8 June 1922. The rundela was turned into the several steps elevated podium, with a stone border which was ornamented with the lion heads from the outside and pigeons from the inside. Due to the lack of time and funds, the animal ornaments were made of papier-mâché, like a theatrical scenography. After the wedding, the cardboard ornaments survived until the fall of 1922 and were disintegrated by the rains. The rundela again remained empty for several years.[32]

In 1927 city administration decided to adapt it into a fountain.[3] It was ceremonially open on 2 April 1927. During winters, in order to prevent the frost damage, the entire fountain was covered with hay, earth and grass on top. It was a constant source of making fun of the city government, which was being accused by the journalists for creating a midden in downtown instead of progressing to the future.[32] The fountain itself though, was considered a beauty: it was made of greenish granite, had sprinklers of different intensity while the bed of the pond was made from Murano glass.[31] In 1947, Dobrović demolished almost everything to the ground level, including the fountain[3] His explanation for the destruction was that the fountain "choked" the traffic.[32]

Terazije Terrace

Terazije Terrace (Serbian: Теразијска тераса, translit. Terazijska Terasa is a sloping park coming down from the 117 m (384 ft) [35] high Terazije Ridge (on top of which Terazije is built) to the right bank of the Sava river, but more specifically coming down to the Zeleni Venac market. Geographically, it is a part of the larger, 300 m (980 ft) long Sava Ridge.

The top of the area is an excellent natural lookout point to the Sava river valley, Novi Beograd and further into the Syrmia region. The future of the terrace is a subject of public and academic debate ever since the 19th century. First general plan for it is from 1912 by the French architect Alban Chamond which envisioned it as the cascades of trapezoid piazzetas with flowers and fountains, leaving the panoramic view intact. In 1923 a project for constructing a terrace-observation point was made. In 1929, Serbian architect Nikola Dobrović's plan was accepted. He projected two tall business buildings on the both ends of the ridge and a plateau between with several small business and leisure objects, while the slope itself would be a succession of horizontal gardens, pools and fountains.[36] At that time, only the upper section was adapted as a park, while the lower section was occupied by the houses in the Kraljice Natalije Street and their backyards. In order to hide that "eyesore" from the view of the people in downtown, a front-type wooden wall made of slats was constructed in the 1930s. It was made like a grid, and the ivy was planted in order to grow around it and to obstruct the view on the lower neighborhood.[1] The houses were demolished after the war, so the park today extends all the way to the Kraljice Natalije.

In the 1990s Dobrović's plan was reactivated, but the temporary park remained and a competition from 1991 resulted only in the large building at the beginning of the Balkanska street which met with disapproval of the public. In 2006 a new tender for architectural solution for Terazije Terrace was organized which resulted in 2008 project by Branislav Redžić which remained only on paper. In 2015, city announced plans to reactivate and adapt Redžić's project, but as of 2018, still no work has been done.[36]

Terazije Tunnel

Terazije Tunnel (Serbian: Теразијски тунел, translit. Terazijski tunel) is a traffic tunnel which passes right beneath Terazije in the east-west direction. Eastern entry point is at the intersection of the Dečanska and Nušićeva streets, while western is the extension of the Brankova street. It is a direct and the closest link between downtown Belgrade and the Branko's Bridge and further to the New Belgrade and Zemun. In one of his projects, architect Dimitrije T. Leko envisioned the tunnel in 1955. In 1957-60 a building was constructed by Zagorka Mešulam which is located at the future entry point from the Nušićeva street. An elevated empty space in the base of the building was built to keep and area for the future descent into the tunnel. The space was hidden behind the wall before the tunnel was built. The tunnel was projected by the Ljubomir Porfirović and Milosav Vidaković and was officially opened on 4 December 1970 by the President of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito and the first lady Jovanka Broz. It was part of the four major official openings on the same day, which also included the Mostar interchange, the highway through Belgrade and the Gazela bridge. Today Terazije tunnel is known as one of the busiest traffic routes in Belgrade and even a short stoppage in it causes widespread traffic jams all over the downtown.[37] On the same day, the underground passage in Nušićeva street, at the entrance into the tunnel, was also opened. First 24/7 supermarket in Belgrade, (in Serbian: dragstor), was opened in the passage. Since then, it deteriorated quite a bit, with only few shops working, despite a partial reconstruction in 2009.[38]

Already in the 1970s it was evident that the tunnel is not adequate for the amount of traffic. A "twin tunnel" for the traffic from the opposite direction was planned. It was to connect the Bulevar kralja Aleksandra and the Branko's Bridge. According to the proposed plans, the traffic would descend underground between the bridge and the Republic Square. In time, several other routes were proposed, like the Branko's Bridge-Bulevar Despota Stefana (Palilula neighborhood), from the Pop Lukina Street at the bridge to the First school of economics at the corner of the Cetinjska and Bulevar Despota Stefana streets. Ultimately, the tunnel wasn't built. In the 2010s the idea of a tunnel resurfaced, but though the exit point at Palilula remained in the new plans, the entry point was moved to the west, near the Old Sava Bridge area.[39]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Dragan Perić (29 April 2018). "Политикин времеплов - Траг о несталом Дугом мосту" [Politika's chronicle - A trace of the missing Long bridge]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1074 (in Serbian). p. 28.

- 1 2 "Ulepšavanje Terazija", Politika (in Serbian), 31 August 1911

- 1 2 3 4 5 Slobodan Giša Bogunović (28 April 2012), "Terazije na novom Beogradu", Politika-Kulturni dodatak (in Serbian)

- ↑ "I trg i ulica Terazije", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Branko Bogdanović (16 September 2018). "Градоначелник коме је пресео "Победник"" [Mayor who got fed up with the "Pobednik"]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1094 (in Serbian). pp. 28–29.

- 1 2 "Opština ruši kućerke i ćumeze u Kuzmanovićevom dvorištu na Terazijama" [Municipality is demolishing the shanties and huts in Kuzmanović Yard in Terazije], Politika (in Serbian), 13 March 1937

- ↑ Ivan Jević (16 October 2014). "Terazije, 17 VIII 1941" (in Serbian). Vreme.

- ↑ N.M. (28 May 2011), "Spomen-ploča obeŠenim rodoljubima", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Tanjug (18 July 2011), "Odata pošta rodoljubima obešenim na Terazijama", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ J. Gajić (15–16 April 2017). "Na praznik padale bombe" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 27.

- ↑ Miloš Lazić (16 September 2018). "Како хор веселих баба продаје робу" [How a choir of cheerful old wives is selling goods]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1094 (in Serbian). pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Belgrade by the 1883 census

- ↑ Претходни резултати пописа становништва и домаће стоке у Краљевини Србији 31 декембра 1910 године, Књига V, стр. 10 [Preliminary results of the census of population and husbandry in Kingdom of Serbia on 31 December 1910, Vol. V, page 10]. Управа државне статистике, Београд (Administration of the state statistics, Belgrade). 1911.

- ↑ Final results of the census of population from 31 January 1921, page 4. Kingdom of Yugoslavia - General State Statistics, Sarajevo. June 1932.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva 1953, Stanovništvo po narodnosti (pdf). Savezni zavod za statistiku, Beograd.

- ↑ Osnovni skupovi stanovništva u zemlji – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1981, tabela 191. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Stanovništvo prema migracionim obeležjima – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1991, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva po mesnim zajednicama, Saopštenje 40/2002, page 4. Zavod za informatiku i statistiku grada Beograda. 26 July 2002.

- 1 2 3 Dejan Aleksić (7–8 April 2018). "Razglednica koje više nema" [Postcards that is no more]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 22.

- ↑ Filmska enciklopedija, knjiga I [Film encyclopedia, Vol. I]. Zagreb: Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. 1986. pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Goran Vesić (14 September 2018). "Прва европска кафана - у Београду" [First European kafana - in Belgrade]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ↑ Zdravko Čolić - "Okano" album

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (26 March 2008), "Bezistan - Pepeljuga ili princeza" [Bezistan - Cinderella or princess], Politika (in Serbian), p. 23

- 1 2 3 Daliborka Mučibabić (24 March 2018). "Novi rok za lepši Bezistan" [New deadline for nicer Bezistan]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Daliborka Mučibabić (20 April 2017), "Bezistan bez kioska, a dobija klupe" [Bezistan without kiosk, new benches will be placed], Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ B.Hadžić (25 May 2012), "Bioskop Kozara izgoreo do temelja" [Cinema Kozara burned to the ground], Večernje Novosti (in Serbian)

- ↑ S.Šulović (27 September 2013), "Beograd spao na 9 bioskopa" [Belgrade came down to only 9 cinemas], 24 sata (in Serbian), p. 3

- 1 2 3 Daliborka Mučibabić (11 October 2018). "Traži se rešenje za novi izgled Čumićevog sokačeta" [A new look for Čumićevo Sokače is being searched for]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (2 December 2010), "Zelena oaza umesto sivog betona", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (27 April 2011), "Umesto buvljaka - zelena oaza", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 3 Dejan Aleksić (30 April 2018). "Svaka nova fontana malo umetničko delo" [Every new fountain (will be) a small work of art]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 19.

- 1 2 3 4 Dragan Perić (11 March 2018). "Politikin vremeplov: Kartonski lavovi prvi ukras Terazijske fontane" [Politika's chronicle: Cardboard lions were the first ornaments of the Terazije fountain]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1067 (in Serbian). p. 28.

- 1 2 Branka Vasiljević (16 September 2017), ""Pobedniku" puca pod nogama" [Cracks beneath "Pobednik’s" feet], Politika (in Serbian), pp. 1 & 15

- ↑ "City of Belgrade - Famous Monuments". City of Belgrade.

- ↑ Statistical Yearbook of Belgrade 2007 - Topography, climate and environment Archived 2011-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Daliborka Mučibabić (6 March 2015). "Terazijska terasa – novi gradski trg" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 15.

- ↑ Zoran Nikolić (18 December 2014). "Metropola se rodila tokom noći" (in Serbian). Večernje novosti.

- ↑ S.D. (April 2010), "Oživljava prolaz u Nušićevoj", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić, Dejan Aleksić (30 September 2018). "Нови саобраћајни тунели под водом, кроз брдо и центар града" [New traffic tunnels under water, through the hill and downtown]. Politika (in Serbian).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terazije. |