Sacred Valley

%2C_Peru.jpg) Sacred Valley of the Incas | |

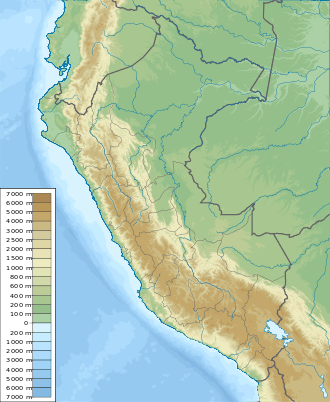

Shown within Peru | |

| Alternative name | Urubamba Valley |

|---|---|

| Location | Cuzco Region, Peru |

| Coordinates | 13°20′00″S 72°05′00″W / 13.33333°S 72.08333°WCoordinates: 13°20′00″S 72°05′00″W / 13.33333°S 72.08333°W |

| Type | valley |

| History | |

| Cultures | Inca |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

.jpg)

The Sacred Valley of the Incas (Spanish: Valle Sagrado de los Incas; Quechua: Willka Qhichwa) or the Urubamba Valley is a valley in the Andes of Peru, 20 kilometres (12 mi) at its closest north of the Inca capital of Cusco. It is located in the present-day Peruvian region of Cusco. In colonial documents it was referred to as the "Valley of Yucay." The Sacred Valley was incorporated slowly into the incipient Inca Empire during the period from 1000 to 1400 CE.[1]

The scenic and historical Sacred Valley is a major tourist destination. In 2013, 1.2 million people, 800,000 of them non-Peruvians, are estimated to have visited Machu Picchu, its most famous archaeological site. Many of the same tourists also visited other archaeological sites and modern towns in the Sacred Valley.

Geography

The valley, running generally west to east, is understood to include everything along the Urubamba River between the town and Inca ruins at Písac westward to Machu Picchu, 100 kilometres (62 mi) distant.[2] The Sacred Valley has elevations above sea level along the river ranging from 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) at Pisac to 2,050 metres (6,730 ft) at the Urubamba River below the citadel of Machu Picchu. On both sides of the river, the mountains rise to much higher elevations, especially to the south where two prominent mountains overlook the valley: Sahuasiray, 5,818 metres (19,088 ft) and Veronica, 5,893 metres (19,334 ft) in elevation. The intensely cultivated valley floor is about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) wide on average. Side valleys and agricultural terraces (andenes) expand the cultivatable area.[3]

The valley was formed by the Urubamba river, also known as the Vilcanota River, Willkanuta River (Aymara, "house of the sun") or Willkamayu (Quechua). The latter, in Quechua, the still spoken lingua franca of the Inca Empire, means the sacred river. It is fed by numerous tributaries which descend through adjoining valleys and gorges, and contains numerous archaeological remains and villages. The Sacred Valley was the most important area for maize production in the heartland of the Inca Empire and access through the valley to tropical areas facilitated the import of products such as coca leaf and chile peppers to Cuzco.[4]

The climate of Urubamba is typical of the valley. Precipitation, concentrated in the months of October through April, totals 527 millimetres (20.7 in) annually and monthly average temperatures range between 15.4 °C (59.7 °F) in November, the warmest month, to 12.2 °C (54.0 °F) in July, the coldest month.[5] The Incas built extensive irrigation works throughout the valley to counter deficiencies and seasonality in precipitation.[6]

History

The early Incas lived in the Cuzco area.[7] By conquest or diplomacy, during the period 1000 to 1400 CE, the Inca achieved administrative control over the various ethnic groups living in or near the Sacred Valley.[8]

The attraction of the Sacred Valley to the Inca, in addition to its proximity to Cuzco, was probably that it was lower in elevation and therefore warmer than any other nearby area. The lower elevation permitted maize to be grown in the Sacred Valley. Maize was a prestige crop for the Incas, especially to make chicha, a fermented maize drink the Incas and their subjects consumed in large quantities at their many ceremonial feasts and religious festivals.[9]

Large scale maize production in the Sacred Valley was apparently facilitated by varieties bred in nearby Moray, either a governmental crop laboratory[10] or a seedling nursery of the Incas.[11]

The Inca customarily divided conquered lands into three more-or-less equal parts. One part was for the emperor (the Sapa Inca), one part for the religious establishment, and one part for the communities of farmers themselves. In the 1400s, the Sacred Valley became an area of royal estates and country homes. Once a royal estate was created by an emperor it continued to be owned by descendants of the emperor after his death.[12] The estate of the emperor Yawar Waqaq (ca. 1380 CE) was located at Paullu and Lamay (a few kilometers downstream from Pisac); Huchuy Qosqo, the estate of the emperor Viracocha Inca (c. 1410-1438), overlooks the Sacred Valley; the estate of Pachacuti (1438-1471 CE) was at Pisac; and the sparse ruins of Quispiguanca. the estate of the emperor Huayna Capac (1493-1527 CE), are in the town of Urubamba.[13] Most archaeologists believe that Machu Picchu was built as an estate for Pachacuti.[14]

Agricultural terraces, called andenes, were built up hillsides flanking the valley floor and are today the most visible and widespread signs of the Inca civilization in the Sacred Valley.[15]

In 1537, the Inca Emperor Manco Inca Yupanqui fought and won the Battle of Ollantaytambo against a Spanish army headed by Hernando Pizarro. Nevertheless, Manco soon withdrew from the Sacred Valley and the area came under the control of the Spanish colonialists.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ Bauer, Brian S.; Covey, R. Alan (2002). "Processes of State Formation in the Inca Heartland (Cuzco, Peru)". American Anthropologist. 104 (3): 846–64. doi:10.1525/aa.2002.104.3.846.

- ↑ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, p. 127

- ↑ Google Earth. Another definition of the area of the Sacred Valley is that it is between Pisaq and Ollantaytambo, a distance of about 60 kilometres (37 mi).

- ↑ Covey, R. Alan (2009), How the Incas built their Heartland, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp 43-44

- ↑ Climate: Urubamba, https://en.climate-data.org/location/44993/, accessed 24 Dec 2016

- ↑ D'Altroy, pp. 127-140

- ↑ Alan Covey, R (2003). "A processual study of Inka state formation". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 22 (4): 333–57. doi:10.1016/S0278-4165(03)00030-8.

- ↑ Bauer and Covey, p. 846

- ↑ D'Altroy, p. 189

- ↑ Earls, John (nd), "The Character of Inca and Andean Agriculture," pp. 18-19. http://macareo.pucp.edu.pe/~jearls/documentosPDF/theCharacter.PDF, accessed 20 dec 2016

- ↑ Plachetka, Uwe Christian; Pietsch, Stephan A. (2009). "El centro vaviloviano en el Perú: un conjunto socio-ecológico frente a riesgos extremos" [The center Vavilov year in Peru: a socio-ecological set against extreme risks] (PDF). Tikpa Pachapaq (in Spanish). 1 (1): 9–16.

- ↑ McEwan, pp 87-88

- ↑ Covey, R. Alan (2009), How the Incas built their Heartland, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, p. 217; Niles, Susan A. (1999), The Shape of Inca History, Iowas City: University of Iowa Press, pp. 133-153. Downloaded from Project Muse.

- ↑ Rowe, John (1990). "Machu Picchu a la luz de documentos de siglo XVI. Historia, 16 (1), pp.139–154

- ↑ Guillet, David and others (1987), "Terracing and Irrigation in the Peruvian Highlands," Current Anthropology, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp. 409-410. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ↑ Hemming, John (1970), The Conquest of the Incas, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, pp 213-232.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sacred Valley. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sacred Valley of the Incas. |