Nazca Lines

Coordinates: 14°43′00″S 75°08′00″W / 14.71667°S 75.13333°W

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

|---|---|

1953 aerial photograph by Maria Reiche, one of the first archaeologists to study the lines | |

| Location | Nazca Desert, Peru |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, iv |

| Reference | 700 |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) |

| Area | 75,358.47 ha |

| Coordinates | 14°43′33″S 75°8′55″W / 14.72583°S 75.14861°W |

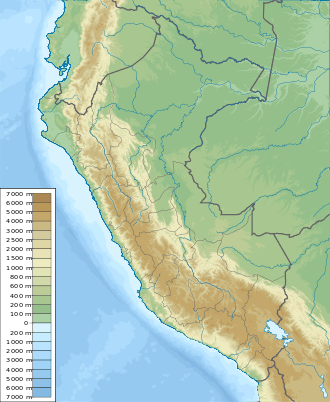

Location of Nazca Lines in Peru | |

The Nazca Lines /ˈnæzkɑː/ are a series of large ancient geoglyphs in the Nazca Desert, in southern Peru. The largest figures are up to 370 m (1,200 ft) long.[1] They were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. Although some local geoglyphs resemble Paracas motifs, scholars believe the Nazca Lines were created by the Nazca culture between 500 BCE and 500 CE.[2] The figures vary in complexity. Hundreds are simple lines and geometric shapes; more than 70 are zoomorphic designs of animals, such as birds, fish, llamas, jaguars, and monkeys, or human figures. Other designs include phytomorphic shapes, such as trees and flowers.

The designs are shallow lines made in the ground by removing naturally occurring reddish pebbles and uncovering the whitish/grayish ground beneath. Scholars differ in interpreting the purpose of the designs, but in general, they ascribe religious significance to them.[3][4][5][6]

Because of its isolation and the dry, windless, stable climate of the plateau, the lines have mostly been preserved naturally. Extremely rare changes in weather may temporarily alter the general designs. As of 2012, the lines are said to have been deteriorating because of an influx of squatters inhabiting the lands.[7]

Contrary to the popular belief that the lines and figures can only be seen from an aircraft, they are visible from the surrounding foothills and other high places.[8][9][10]

Location

The high, arid plateau stretches more than 80 km (50 mi) between the towns of Nazca and Palpa on the Pampas de Jumana, approximately 400 km (250 mi) south of Lima, roughly matching the main PE-1S Panamericana Sur, with a main concentration in a 10 by 4 kilometers rectangle, south of San Miguel de la Pascana hamlet. In this area, the most notable geoglyphes are visible.

History

The first published mention of the Nazca Lines was by Pedro Cieza de León in his book of 1553, and he mistook them for trail markers.[11] Although partially visible from the nearby hills, the first to report them were Peruvian military and civilian pilots. In 1927 the Peruvian archaeologist Toribio Mejía Xesspe spotted them while he was hiking through the foothills. He discussed them at a conference in Lima in 1939.[12][13].

Paul Kosok, a historian from Long Island University, is credited as the first scholar to study the Nazca Lines. In the country in 1940–41 to study ancient irrigation systems, he flew over the lines and realized one was in the shape of a bird. Another chance observation helped him see how lines converged at the winter solstice in the Southern Hemisphere. He began to study how the lines might have been created, as well as to try to determine their purpose. He was joined by Maria Reiche, a German mathematician and archaeologist, to help determine the purpose of the Nazca Lines. They proposed one of the earliest reasons for the existence of the figures: to be markers on the horizon to show where the sun and other celestial bodies rose on significant dates. Archaeologists, historians, and mathematicians have all tried to determine the purpose of the lines.

Determining how they were made has been easier than determining why they were made. Scholars have theorized the Nazca people could have used simple tools and surveying equipment to construct the lines. Archaeological surveys have found wooden stakes in the ground at the end of some lines, which supports this theory. One such stake was carbon-dated and was the basis for establishing the age of the design complex.

Refuting the hypothesis of Erich von Däniken that the lines had to have been created by "ancient astronauts", prominent skeptic Joe Nickell has reproduced the figures using tools and technology available to the Nazca people. Scientific American called his work "remarkable in its exactness" when compared to the lines.[14] With careful planning and simple technologies, he proved that a small team of people could recreate even the largest figures within days, without any aerial assistance.[13]

Most of the lines are formed on the ground by a shallow trench with a depth between 10 and 15 cm (4 and 6 in). Such trenches were made by removing the reddish-brown iron oxide-coated pebbles that cover the surface of the Nazca Desert. When this gravel is removed, the light-colored clay earth exposed in the bottom of the trench produces lines and contrasts sharply in color and tone with the surrounding land surface. This sublayer contains high amounts of lime which, with the morning mist, hardens to form a protective layer that shields the lines from winds, thereby preventing erosion.

The Nazca "drew" several hundred simple, but huge, curvilinear animal and human figures by this technique. In total, the earthwork project is huge and complex: the area encompassing the lines is nearly 450 km2 (170 sq mi), and the largest figures can span nearly 370 m (1,200 ft).[1] Some of the measurements for the figures conclude that the hummingbird is 93 m (310 ft) long, the condor is 134 m (440 ft), the monkey is 93 m (310 ft) by 58 m (190 ft), and the spider is 47 m (150 ft). The extremely dry, windless, and constant climate of the Nazca region has preserved the lines well. This desert is one of the driest on Earth and maintains a temperature near 25 °C year round. The lack of wind has helped keep the lines uncovered and visible.

The discovery of two new small figures was announced in early 2011 by a Japanese team from Yamagata University. One of these resembles a human head and is dated to the early period of Nazca culture or earlier, and the other, undated, is an animal. In March 2012, the university announced a new research center would be opened at the site in September 2012 to study the area for the next 15 years. The team has been conducting field work there since 2006, when it had found approximately 100 new geoglyphs.[15][16]

Earlier Paracas geoglyphs

The Paracas culture is considered the precursor that influenced the development of the Nazca Lines. In 2018, drones used by archaeologists revealed many geoglyphs in the Palpa province that are being assigned to the Paracas culture. Many predate the associated Nazca lines by a thousand years, and some demonstrate a significant difference in the subjects and locations, such as some being on hillsides.[17] Co-discoverer, Peruvian archaeologist Luis Jaime Castillo Butters indicates that many of these newly discovered geoglyphs represent warriors.

Purpose

Anthropologists, ethnologists, and archaeologists have studied the ancient Nazca culture to try to determine the purpose of the lines and figures. One hypothesis is that the Nazca people created them to be seen by deities in the sky. Paul Kosok and Maria Reiche advanced a purpose related to astronomy and cosmology: the lines were intended to act as a kind of observatory, to point to the places on the distant horizon where the sun and other celestial bodies rose or set in the solstices. Many prehistoric indigenous cultures in the Americas and elsewhere constructed earthworks that combined such astronomical sighting with their religious cosmology, as did the late Mississippian culture at Cahokia in present-day United States. Another example is Stonehenge in England.

Gerald Hawkins and Anthony Aveni, experts in archaeoastronomy, concluded in 1990 that the evidence was insufficient to support such an astronomical explanation.[18]

Maria Reiche asserted that some or all of the figures represented constellations. By 1998, Phyllis B. Pitluga, a protégé of Reiche and senior astronomer at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, had concluded that the animal figures were "representations of heavenly shapes". According to The New York Times, "she contends they are not shapes of constellations, but of what might be called counter constellations, the irregularly-shaped dark patches within the twinkling expanse of the Milky Way."[19] Aveni criticized her work for failing to account for all the details.

Alberto Rossell Castro (1977) proposed a multifunctional interpretation of the geoglyphs, which were divided into three groups, among which the first was given by tracks connected to irrigation and field division, the second includes the lines as axes connected with mounds and cairns, the third was linked to astronomical interpretations. [20]

In 1985, archaeologist Johan Reinhard published archaeological, ethnographic, and historical data demonstrating that worship of mountains and other water sources predominated in Nazca religion and economy from ancient to recent times. He theorized that the lines and figures were part of religious practices involving the worship of deities associated with the availability of water, which directly related to the success and productivity of crops. He interpreted the lines as sacred paths leading to places where these deities could be worshiped. The figures were symbols representing animals and objects meant to invoke the aid of the deities in supplying water. The precise meanings of many of the individual geoglyphs remain unknown.

Henri Stierlin, a Swiss art historian specializing in Egypt and the Middle East, published a book in 1983 linking the Nazca Lines to the production of ancient textiles that archeologists have found wrapping mummies of the Paracas culture.[21] He contended that the people may have used the lines and trapezes as giant, primitive looms to fabricate the extremely long strings and wide pieces of textiles typical of the area. According to his theory, the figurative patterns (smaller and less common) were meant only for ritualistic purposes. This theory is not widely accepted, although scholars have noted similarities in patterns between the textiles and the Nazca Lines, which they interpret as sharing in a common culture.

The first systematic field study of the geoglyphs is due to Markus Reindel and Johny Cuadrado Island who since 1996 documented and excavated more than 650 sites. The iconographical comparison between the ceramics found the figurative motifs of geoglyphs has led archaeologists to conclude that the lines were made between 200 and 600 BC. C. [22]

Another contribution in the interpretation of Nazca Lines was proposed by Johnson who, on the basis of the results obtained by geophysical investigations and the observation of geological faults, argued that some geoglyphs followed the paths of aquifers from which aqueducts (or puquios) collected water [23]

A recent research [24] conducted by Nicola Masini and Giuseppe Orefici in Pampa de Atarco (at about 10 km south of Pampa de Nasca), revealed a spatial, functional and religious relationship between these geoglyphs and the temples of Cahuachi. In particular, the investigations performed using remote sensing techniques put in evidence "five groups of geoglyphs, each of them characterized by a specific motif and shape, and associated with a distinct function" [25]: from the ceremonial one, given by meandering motifs, to calendarical one, as proved by the presence of radial centers aligned along the directions of winter solstice and equinox sunset. For the two Italian scholars the geoglyphs were the venues of events linked to agriculture calendar and served to strengthen social cohesion among various groups of pilgrims, sharing common ancestors and religious beliefs [26]

Alternative explanations

Other theories were that the geometric lines could indicate water flow or irrigation schemes, or be a part of rituals to "summon" water. The spiders, birds, and plants may be fertility symbols. It also has been theorized that the lines could act as an astronomical calendar.[27]

Phyllis Pitluga, senior astronomer at the Adler Planetarium and a protégé of Reiche, performed computer-aided studies of star alignments. She asserted the giant spider figure is an anamorphic diagram of the constellation Orion. She further suggested that three of the straight lines leading to the figure were used to track the changing declinations of the three stars of Orion's Belt. In a critique of her analysis, Dr. Anthony F. Aveni noted she did not account for the other 12 lines of the figure. He commented generally on her conclusions, saying:

I really had trouble finding good evidence to back up what she contended. Pitluga never laid out the criteria for selecting the lines she chose to measure, nor did she pay much attention to the archaeological data Clarkson and Silverman had unearthed. Her case did little justice to other information about the coastal cultures, save applying, with subtle contortions, Urton's representations of constellations from the highlands. As historian Jacquetta Hawkes might ask: was she getting the pampa she desired?[28]

Jim Woodmann[29] theorized that the Nazca lines could not have been made without some form of flight to observe the figures properly. Based on his study of available technology, he suggests a hot-air balloon was the only possible means of flight at the time of construction. To test this hypothesis, Woodmann made a hot-air balloon using materials and techniques he understood to have been available to the Nazca people. The balloon flew, after a fashion. Most scholars have rejected Woodmann's thesis as ad hoc,[13] because of the lack of any evidence of such balloons.[30]

Preservation and environmental concerns

People trying to preserve the Nazca Lines are concerned about threats of pollution and erosion caused by deforestation in the region.

The Lines themselves are superficial, they are only 10 to 30 cm deep and could be washed away... Nazca has only ever received a small amount of rain. But now there are great changes to the weather all over the world. The Lines cannot resist heavy rain without being damaged.

– Viktoria Nikitzki of the Maria Reiche Centre[31]

After flooding and mudslides in the area in mid-February 2007, Mario Olaechea Aquije, archaeological resident from Peru's National Institute of Culture, and a team of specialists surveyed the area. He said, "[T]he mudslides and heavy rains did not appear to have caused any significant damage to the Nazca Lines", but he noted that the nearby Southern Pan-American Highway did suffer damage, and "the damage done to the roads should serve as a reminder to just how fragile these figures are."[32]

In 2013, machinery used in a limestone quarry was reported to have destroyed a small section of a line, and caused damage to another.[33]

In December 2014, Greenpeace activists irreparably damaged the Nazca Lines while setting up a banner within the lines of one of the famed geoglyphs. The activists damaged an area around the hummingbird by grinding rocks into the sandy soil. Access to the area around the lines is strictly prohibited[34][35] and special shoes must be worn to avoid damaging the UN World Heritage site. Greenpeace claimed the activists were "absolutely careful to protect the Nazca lines,"[36] but this is contradicted by video and photographs showing the activists wearing conventional shoes (i.e. not special protective shoes) while walking on the site.[37][38] Greenpeace has apologized to the Peruvian people,[39] but Luis Jaime Castillo, Peru's vice minister of cultural heritage, called the apology "a joke", because Greenpeace initially refused to identify the vandals or accept responsibility.[40] Culture Minister Diana Alvarez-Calderon said that evidence gathered during an investigation by the government would be used as part of a legal suit against Greenpeace. "The damage done is irreparable and the apologies offered by the environmental group aren't enough," she said at a news conference.[34] Facing increasing pressure, Greenpeace later released the identities of four of the activists involved.[41] One of the activists, Wolfgang Sadik, was eventually given a fine and a suspended prison sentence for his role in the incident.[42]

The Greenpeace incident also directed attention to other damage to geoglyphs outside of the World Heritage area caused in 2012 and 2013 by off-road vehicles of the Dakar Rally,[43] visible from satellite imagery.[44]

In January 2018, an errant truck driver was arrested, but later released for lack of evidence indicating any intent other than simple error, despite damage to three of the geoglyphs, leaving substantial tire marks across an area of approximately 150 by 350 feet.[45]

Images

- The Hummingbird

- The Condor

The Heron

The Heron- The Whale

- The Human

- The Spider

- The Pelican

- The Dog

- The Tree

- The Monkey

Phytomorphic glyphs

Phytomorphic glyphs- Hands

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Golomb, Jason. "Nasca Lines – The Sacred Landscape". National Geographic. National Geographic. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ Unesco World Heritage (2009). "Lines and Geoglyphs of Nasca and Pampas de Jumana".

- ↑ Helaine Selin. Nature Across Cultures: Views of Nature and the Environment in Non-Western Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media; 17 April 2013. ISBN 978-94-017-0149-5. p. 286–.

- ↑ Richard A. Freund. Digging Through History: Archaeology and Religion from Atlantis to the Holocaust. Rowman & Littlefield; 27 October 2016. ISBN 978-1-4422-0883-4. p. 22–.

- ↑ Mary Strong. Art, Nature, and Religion in the Central Andes: Themes and Variations from Prehistory to the Present. University of Texas Press; 1 May 2012. ISBN 978-0-292-73571-2. p. 33–.

- ↑ Religion and the Environment. Palgrave Macmillan UK; 3 June 2016. ISBN 978-0-230-28634-4. p. 110–.

- ↑ Taj, Mitra (August 15, 2012). "Pigs and squatters threaten Peru's Nazca lines". Reuters. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ↑ Gardner's Art Through the Ages: Ancient, medieval, and non-European art. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1 January 1991. ISBN 978-0-15-503770-0.

- ↑ Hinman, Bonnie. Mystery of the Nazca Lines. ABDO; 1 January 2016. ISBN 978-1-68077-242-5. p. 6–.

- ↑ Anthony F. Aveni. Between the Lines: The Mystery of the Giant Ground Drawings of Ancient Nasca, Peru. University of Texas Press; 2000. ISBN 978-0-292-70496-1. p. 88–.

- ↑ In the Antwerp edition of 1554, see: Pedro Cieza de León, La Chronica del Peru (The chronicle of Peru), (Antwerp, (Belgium): Martin Nucio, 1554), page 141. On page 141, Cieza discussed the Nazca region of Peru and then mentioned that: " … y por algunas partes delos arenales se veen señales, paraque atinen el camino que han de lleuar." ( … and in some parts of the desert are seen signals, so that they [i.e., the Indians] find the path that has to be taken.)

In 1586, Luis Monzón reported having seen ancient ruins in Peru, including the remains of "roads": Luis Monzón (1586) "Descripcion de la tierra del repartimiento de los rucanas antamarcas de la corona real, jurisdicion de la ciudad de Guamanga. año de 1586." in: Marcos Jiménez de la Espada, ed., Relaciones geográficas de Indias: Peru, volume 1 (Madrid, Spain: Manuel G. Hernandez, 1881), pp. 197–216. On page 210, Munzón mentioned seeing ancient ruins, including " … y hay señales de calles." (… and there are signs of streets.) Munzón asked elderly Indians about the ruins. They told him that before the Incas, a people whom " … llamaron viracochas, …" (… they called viracochas …) inhabited the area, and "A éstos les hacian caminos, que hoy dia son vistos, tan anchos como una calle … " (To those [places] they made paths, that are seen today, as wide as a street … .) - ↑ Mejía Xesspe, Toribio (1939) "Acueductos y caminos antiguos de la hoya del Río Grande de Nazca" (Aqueducts and ancient roads of the Rio Grand valley in Nazca), Actas y Trabajos Cientificos del 27 Congreso Internacional de Americanistas (Proceedings and scientific works of the 27th international congress of American anthropologists), 1: 559–69.

- 1 2 3 Katherine Reece, "Grounding the Nasca Balloon", Into the Hall of Ma'at website

- ↑ Nickell, Joe (2005). Unsolved History: Investigating Mysteries of the Past, The University Press of Kentucky ISBN 978-0-8131-9137-9, pp. 13–16

- ↑ "Team finds more Peru geoglyphs". Japan Times. Jan 20, 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-07-15. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ "University to open center at Nazca Lines". Japan Times. March 22, 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Greshko, Michael, Exclusive: Massive Ancient Drawings Found in Peruvian Desert, National Geographic, April 5, 2018

- ↑ Cameron, Ian (1990). Kingdom of the Sun God: A History of the Andes and Their People. New York: Facts on File. p. 46. ISBN 0-8160-2581-9.

- ↑ ROBERT McG. THOMAS Jr, "Maria Reiche, 95, Keeper of an Ancient Peruvian Puzzle, Dies", The New York Times, 15 June 1998

- ↑ Rossel Castro, Albert (1977) Arqueología Sur del Perú, Editorial Universo, Lima.

- ↑ Stierlin (1983)

- ↑ Reindel and Wagner, 2009

- ↑ Johnson et al. 2002

- ↑ Masini et al. 2016

- ↑ Masini et al. 2016, p. 239

- ↑ Masini et al. 2016, p. 277.

- ↑ Brown, Cynthia Stokes (2007). Big History. New York: The New Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-59558-196-9.

- ↑ Aveni, Anthony F. Between the Lines: The Mystery of the Giant Ground Drawings of Ancient Nasca, Peru . Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. 1 July 2006 ISBN 0-292-70496-8 p.205

- ↑ "The Theory of Jim Woodman - Science in the Sand". Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ Haughton (2007)

- ↑ Shafik Meghji, "Flooding and tourism threaten Peru's mysterious Nazca Lines", The Independent, July 17, 2004. Accessed April 02, 2007.

- ↑ Living in Peru. "Peru: Nazca Lines escape mudslides", Living in Peru, February 20, 2007. Accessed April 02, 2007.

- ↑ Manuel Vigo (2013-03-14). "Peru: Heavy machinery destroys Nazca lines". Peru this Week. Archived from the original on 2013-07-29. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

- 1 2 Kozak, Robert (2014-12-14). "Peru Says Greenpeace Permanently Damaged Nazca Lines". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2015-02-03.

- ↑ Neuman, William (12 December 2014). "Peru is Indignant After Greenpeace Makes Its Mark on Ancient Site". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ↑ Briceno, Franklin (December 9, 2014). "Peru Riled by Greenpeace Stunt at Nazca Lines". Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Video of Greenpeace Nazca Lines Protest". Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ↑ Vice News: "Drone Footage Shows Extent of Damage From Greenpeace Stunt at Nazca Lines" By Kayla Ruble December 17, 2014

- ↑ "Greenpeace sorry for Nazca lines stunt in Peru". December 11, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Greenpeace Won't Name Activists Linked to Damage". 16 December 2014. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014.

- ↑ "Greenpeace identifies four suspects linked to protest at famed Nazca Lines site". January 21, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Greenpeace activist fined, sentenced for damaging Nazca Lines in Peru". May 20, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ↑ Dube, Ryan; Kozak, Robert (December 28, 2014). "Peruvians Spar Over Protecting Ancient Sites". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 16, 2015. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Hesse R. Combining Structure-from-Motion with high and intermediate resolution satellite images to document threats to archaeological heritage in arid environments. Journal of Cultural Heritage 16 (2015), pp. 192–201

- ↑ Rosenberg, Eli (Feb 1, 2018). "A truck driver inexplicably plowed over a 2,000-year-old site in Peru, damaging the designs". Washington Post.

References

- Aveni, Anthony F. (ed.) (1990). The Lines of Nazca. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-183-3

- Haughton, Brian. (2007). Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries. Career Press. ISBN 1-56414-897-1

- Johnson, Emma. 2007. The 'Mysterious' Nazca Lines. PARA Web Bibliography B-01.

- Johnson, D. W., Proulx. D. A., Mabee, S. B. (2002). The correlation between geoglyphs and subterranean water resources in the Rio Grande de Nasca drainage. In Silvermann H. & Isbell W. H. (Ed.), Andean Archaeology II: art, landscape, and society. New York, Kluwer Academic, pp. 307-332.

- Kosok, Paul (1965). Life, Land and Water in Ancient Peru, Brooklyn: Long Island University Press.

- Lambers, Karsten (2006). The Geoglyphs of Palpa, Peru: Documentation, Analysis, and Interpretation. Lindensoft Verlag, Aichwald/Germany. ISBN 3-929290-32-4

- Masini, Nicola, Orefici, Giuseppe, Danese, M., Pecci, A., Scavone, M., Lasaponara, R. (2016). Cahuachi and Pampa de Atarco: Towards Greater Comprehension of Nasca Geoglyphs. In: Lasaponara R., Masini N., Orefici G. (Eds). The Ancient Nasca World New Insights from Science and Archaeology. Springer International Publishing, pp. 239-278.

- Nickell, Joe. 1983. Skeptical Inquirer The Nazca Lines Revisited: Creation of a Full-Sized Duplicate.

- Reindel, Marcus, Wagner, Günther A. (2009) (Eds.) New Technologies for Archaeology: Multidisciplinary Investigations in Nasca and Palpa, Peru. Springer, Heidelberg, Berlin

- Reinhard, Johan (1996) (6th ed.) The Nazca Lines: A New Perspective on their Origin and Meaning. Lima: Los Pinos. ISBN 84-89291-17-9

- Sauerbier, Martin. GIS-based Management and Analysis of the Geoglyphs in the Palpa Region. ETH (2009). doi:10.3929/ethz-a-005940066.

- Stierlin, Henri (1983). La Clé du Mystère. Paris: Albin Michel. ISBN 2-226-01864-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nazca lines. |