Chili pepper

The chili pepper (also chile pepper, chilli pepper, or simply chilli[1]) from Nahuatl chīlli Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈt͡ʃiːli] (![]()

Chili peppers originated in Mexico.[3] After the Columbian Exchange, many cultivars of chili pepper spread across the world, used for both food and traditional medicine.

Worldwide in 2014, 32.3 million tonnes of green chili peppers and 3.8 million tonnes of dried chili peppers were produced.[4] China is the world's largest producer of green chillies, providing half of the global total.

History

Chili peppers have been a part of the human diet in the Americas since at least 7500 BCE. The most recent research shows that chili peppers were domesticated more than 6,000 years ago in Mexico, in the region that extends across southern Puebla and northern Oaxaca to southeastern Veracruz,[5] and were one of the first self-pollinating crops cultivated in Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America.[6]

Peru is considered the country with the highest cultivated Capsicum diversity because it is a center of diversification where varieties of all five domesticates were introduced, grown, and consumed in pre-Columbian times. Bolivia is considered to be the country where the largest diversity of wild Capsicum peppers is consumed. Bolivian consumers distinguish two basic forms: ulupicas, species with small round fruits including C. eximium, C. cardenasii, C. eshbaughii, and C. caballeroi landraces; and arivivis with small elongated fruits including C. baccatum var. baccatum and C. chacoense varieties.[7]

Christopher Columbus was one of the first Europeans to encounter them (in the Caribbean), and called them "peppers" because they, like black pepper of the genus Piper known in Europe, have a spicy, hot taste unlike other foodstuffs. Upon their introduction into Europe, chilies were grown as botanical curiosities in the gardens of Spanish and Portuguese monasteries. Christian monks experimented with the culinary potential of chili and discovered that their pungency offered a substitute for black peppercorns.[8]

Chilies were cultivated around the globe after indigenous people shared them with travelers.[9][10] Diego Álvarez Chanca, a physician on Columbus' second voyage to the West Indies in 1493, brought the first chili peppers to Spain and first wrote about their medicinal effects in 1494.

The spread of chili peppers to Asia was most likely a natural consequence of its introduction to Portuguese traders (Lisbon was a common port of call for Spanish ships sailing to and from the Americas) who, aware of its trade value, would have likely promoted its commerce in the Asian spice trade routes then dominated by Portuguese and Arab traders.[11] It was introduced in India by the Portuguese towards the end of 15th century.[12] Today chilies are an integral part of Indian and Southeast Asian cuisines.

The chili pepper features heavily in the cuisine of the Goan region of India, which was the site of a Portuguese colony (e.g., vindaloo, an Indian interpretation of a Portuguese dish). Chili peppers journeyed from India,[13] through Central Asia and Turkey, to Hungary, where they became the national spice in the form of paprika.

An alternate, although not so plausible account (no obvious correlation between its dissemination in Asia and Spanish presence or trade routes), defended mostly by Spanish historians, was that from Mexico, at the time a Spanish colony, chili peppers spread into their other colony the Philippines and from there to India, China, Indonesia. To Japan, it was brought by the Portuguese missionaries in 1542, and then later, it was brought to Korea.

In 1995 archaeobotanist Hakon Hjelmqvist published an article in Svensk Botanisk Tidskrift claiming there was evidence for the presence of chili peppers in Europe in pre-Columbian times.[14] According to Hjelmqvist, archaeologists at a dig in St Botulf in Lund found a Capsicum frutescens in a layer from the 13th century. Hjelmqvist thought it came from Asia. Hjelmqvist also said that Capsicum was described by the Greek Theophrastus (370–286 BCE) in his Historia Plantarum, and in other sources. Around the first century CE, the Roman poet Martial mentioned Piperve crudum (raw pepper) in Liber XI, XVIII, allegedly describing them as long and containing seeds (a description which seems to fit chili peppers - but could also fit the long pepper, which was well known to ancient Romans).

Contrary to the Columbian Exchange, evidence of the use of chili peppers in Southeast Asia can be found in stone inscriptions from the Bagan period of the thirteenth-century Myanmar. The Shwe-Kun-Cha Pagoda stone inscriptions (1223 CE) of King Nadoungmya (1234 – 1254 CE) included five baskets of chillies in the list of his donations to the pagoda and a slightly later stone inscription (1248 CE) of Princess A-Saw-Kyaum, alternative transliteration Asawgyun, included chillies alongside rice, betel nut, and salt in the cost of her merit makings.[15] [16]

Production

| Green chili production – 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (millions of tonnes) |

In 2014, world production of fresh green chillies and peppers was 33.2 million tonnes, led by China with 48% of the global total.[4] Global production of dried chillies and peppers was about nine times less than for fresh production, led by India with 32% of the world total.[4]

Species and cultivars

The five domesticated species of chili peppers are as follows:

- Capsicum annuum, which includes many common varieties such as bell peppers, wax, cayenne, jalapeños, chiltepin, and all forms of New Mexico chile.

- Capsicum frutescens, which includes malagueta, tabasco and Thai peppers, piri piri, and Malawian Kambuzi

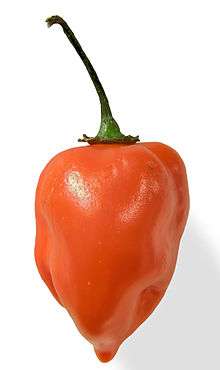

- Capsicum chinense, which includes the hottest peppers such as the naga, habanero, Datil and Scotch bonnet

- Capsicum pubescens, which includes the South American rocoto peppers

- Capsicum baccatum, which includes the South American aji peppers

Though there are only a few commonly used species, there are many cultivars and methods of preparing chili peppers that have different names for culinary use. Green and red bell peppers, for example, are the same cultivar of C. annuum, immature peppers being green. In the same species are the jalapeño, the poblano (which when dried is referred to as ancho), New Mexico, serrano, and other cultivars.

Peppers are commonly broken down into three groupings: bell peppers, sweet peppers, and hot peppers. Most popular pepper varieties are seen as falling into one of these categories or as a cross between them.

Intensity

The substances that give chili peppers their pungency (spicy heat) when ingested or applied topically are capsaicin (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) and several related chemicals, collectively called capsaicinoids.[17][18] The quantity of capsaicin varies by variety, and on growing conditions. Water stressed peppers usually produce stronger pods. When a habanero plant is stressed, for example low water, the concentration of capsaicin increases in some parts of the fruit.[19]

When peppers are consumed by mammals such as humans, capsaicin binds with pain receptors in the mouth and throat, potentially evoking pain via spinal relays to the brainstem and thalamus where heat and discomfort are perceived.[20] The intensity of the "heat" of chili peppers is commonly reported in Scoville heat units (SHU). Historically, it was a measure of the dilution of an amount of chili extract added to sugar syrup before its heat becomes undetectable to a panel of tasters; the more it has to be diluted to be undetectable, the more powerful the variety, and therefore the higher the rating.[21] The modern method is a quantitative analysis of SHU using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to directly measure the capsaicinoid content of a chili pepper variety. Pure capsaicin is a hydrophobic, colorless, odorless, and crystalline-to-waxy solid at room temperature, and measures 16,000,000 SHU.

Capsaicin is produced by the plant as a defense against mammalian predators and microbes, in particular a fusarium fungus carried by hemipteran insects that attack certain species of chillies, according to one study.[22] Peppers increased the quantity of capsaicin in proportion to the damage caused by fungal predation on the plant's seeds.[22]

Common peppers

.jpg)

A wide range of intensity is found in commonly used peppers:

Bell pepper 0 SHU New Mexico green chile 0–70,000 SHU Fresno, jalapeño 3,500–10,000 SHU Cayenne 30,000–50,000 SHU Piri piri 50,000–100,000 SHU Habanero, Scotch bonnet, bird's eye 100,000–350,000 SHU[23]

Notable hot chili peppers

Some of the world's hottest chili peppers are:

Pepper X 3.18M SHU[24]

Dragon's Breath 2.4M SHU[25]

Carolina Reaper 2.2M SHU[26]

Trinidad moruga scorpion 2.0M SHU[27]

Bhut jolokia (Ghost pepper) 1.58M SHU[28]

Trinidad Scorpion Butch T 1.463M SHU[29]

Naga Viper 1.4M SHU[30]

Infinity chili 1.2M SHU[31]

Uses

Culinary uses

.jpg)

Chili pepper pods, which are berries, are used fresh or dried. Chilies are dried to preserve them for long periods of time, which may also be done by pickling.

Dried chilies are often ground into powders, although many Mexican dishes including variations on chiles rellenos use the entire chili. Dried whole chilies may be reconstituted before grinding to a paste. The chipotle is the smoked, dried, ripe jalapeño.

Many fresh chilies such as poblano have a tough outer skin that does not break down on cooking. Chilies are sometimes used whole or in large slices, by roasting, or other means of blistering or charring the skin, so as not to entirely cook the flesh beneath. When cooled, the skins will usually slip off easily.

The leaves of every species of Capsicum are edible. Though almost all other Solanaceous crops have toxins in their leaves, chili peppers do not. The leaves, which are mildly bitter and nowhere near as hot as the fruit, are cooked as greens in Filipino cuisine, where they are called dahon ng sili (literally "chili leaves"). They are used in the chicken soup tinola.[32] In Korean cuisine, the leaves may be used in kimchi.[33] In Japanese cuisine, the leaves are cooked as greens, and also cooked in tsukudani style for preservation.

Chili is a staple fruit in Bhutan. Bhutanese call this crop ema (in Dzongkha) or solo (in Sharchop). The ema datsi recipe is entirely made of chili mixed with local cheese.

In India, most households always keep a stock of fresh hot green chilies at hand, and use them to flavor most curries and dry dishes. It is typically lightly fried with oil in the initial stages of preparation of the dish. Some states in India, such as Rajasthan, make entire dishes only by using spices and chilies.

Chilies are present in many cuisines. Some notable dishes other than the ones mentioned elsewhere in this article include:

- Arrabbiata sauce from Italy is a tomato-based sauce for pasta always including dried hot chilies.

- Puttanesca sauce is tomato-based with olives, capers, anchovy and, sometimes, chilies.

- Paprikash from Hungary uses significant amounts of mild, ground, dried chilies, known as paprika, in a braised chicken dish.

- Chiles en nogada from the Puebla region of Mexico uses fresh mild chilies stuffed with meat and covered with a creamy nut-thickened sauce.

- Curry dishes usually contain fresh or dried chillies.

- Kung pao chicken (Mandarin Chinese: 宫保鸡丁 gōng bǎo jī dīng) from the Sichuan region of China uses small hot dried chilies briefly fried in oil to add spice to the oil then used for frying.

- Mole poblano from the city of Puebla in Mexico uses several varieties of dried chilies, nuts, spices, and fruits to produce a thick, dark sauce for poultry or other meats.

- Nam phrik are traditional Thai chili pastes and sauces, prepared with chopped fresh or dry chilies, and additional ingredients such as fish sauce, lime juice, and herbs, but also fruit, meat or seafood.

- 'Nduja, a more typical example of Italian spicy specialty, from the region of Calabria, is a soft pork sausage made "hot" by the addition of the locally grown variety of jalapeño chili.

- Paprykarz szczeciński is a Polish fish paste with rice, onion, tomato concentrate, vegetable oil, chili pepper powder and other spices.

- Sambal terasi or sambal belacan is a traditional Indonesian and Malay hot condiment made by frying a mixture of mainly pounded dried chillies, with garlic, shallots, and fermented shrimp paste. It is customarily served with rice dishes and is especially popular when mixed with crunchy pan-roasted ikan teri or ikan bilis (sun-dried anchovies), when it is known as sambal teri or sambal ikan bilis. Various sambal variants existed in Indonesian archipelago, among others are sambal badjak, sambal oelek, sambal pete (prepared with green stinky beans) and sambal pencit (prepared with unripe green mango).

- Som tam, a green papaya salad from Thai and Lao cuisine, traditionally has, as a key ingredient, a fistful of chopped fresh hot Thai chili, pounded in a mortar.

Fresh or dried chilies are often used to make hot sauce, a liquid condiment—usually bottled when commercially available—that adds spice to other dishes. Hot sauces are found in many cuisines including harissa from North Africa, chili oil from China (known as rāyu in Japan), and sriracha from Thailand. Dried chilies are also used to infuse cooking oil.

Ornamental plants

The contrast in colour and appearance makes chili plants interesting to some as a purely decorative garden plant.

- Black pearl pepper: small cherry-shaped fruits and dark brown to black leaves Black pearl pepper

- Black Hungarian pepper: green foliage, highlighted by purple veins and purple flowers, jalapeño-shaped fruits [34]

- Bishop's crown pepper, Christmas bell pepper: named for its distinct three-sided shape resembling a red bishop’s crown or a red Christmas bell[35]

Psychology

Psychologist Paul Rozin suggests that eating chilies is an example of a "constrained risk" like riding a roller coaster, in which extreme sensations like pain and fear can be enjoyed because individuals know that these sensations are not actually harmful. This method lets people experience extreme feelings without any risk of bodily harm.[36]

Medicinal

Capsaicin, the chemical in chili peppers that makes them hot, is used as an analgesic in topical ointments, nasal sprays, and dermal patches to relieve pain.[37]

Chemical irritants

Capsaicin extracted from chilies is used in manufacturing pepper spray and tear gas as chemical irritants, forms of less-lethal weapons for control of unruly individuals or crowds.[38] Such products have considerable potential for misuse, and may cause injury or death.[38]

Crop defense

Conflicts between farmers and elephants have long been widespread in African and Asian countries, where elephants nightly destroy crops, raid grain houses, and sometimes kill people. Farmers have found the use of chilies effective in crop defense against elephants. Elephants do not like capsaicin, the chemical in chilies that makes them hot. Because the elephants have a large and sensitive olfactory and nasal system, the smell of the chili causes them discomfort and deters them from feeding on the crops. By planting a few rows of the pungent fruit around valuable crops, farmers create a buffer zone through which the elephants are reluctant to pass. Chilly dung bombs are also used for this purpose. They are bricks made of mixing dung and chili, and are burned, creating a noxious smoke that keeps hungry elephants out of farmers' fields. This can lessen dangerous physical confrontation between people and elephants.[39]

Food defense

Birds do not have the same sensitivity to capsaicin, because it targets a specific pain receptor in mammals. Chili peppers are eaten by birds living in the chili peppers' natural range, possibly contributing to seed dispersal and evolution of the protective capsaicin in chili peppers.[40]

Nutritional value

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 166 kJ (40 kcal) |

|

8.8 g | |

| Sugars | 5.3 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.5 g |

|

0.4 g | |

|

1.9 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

6% 48 μg5% 534 μg |

| Vitamin B6 |

39% 0.51 mg |

| Vitamin C |

173% 144 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Iron |

8% 1 mg |

| Magnesium |

6% 23 mg |

| Potassium |

7% 322 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 88 g |

| Capsaicin | 0.01g – 6 g |

| |

|

†Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

While red chilies contain large amounts of vitamin C (table), other species contain significant amounts of provitamin A beta-carotene.[41] In addition, peppers are a rich source of vitamin B6 (see table).

Spelling and usage

The three primary spellings are chili, chile and chilli, all of which are recognized by dictionaries.

- Chili is widely used in historically Anglophone regions of the United States[42] and Canada.[43] However, it is also commonly used as a short name for chili con carne (literally "chili with meat"). Most versions are seasoned with chili powder, which can refer to pure dried, ground chili peppers, or to a mixture containing other spices.

- Chile is the most common Spanish spelling in Mexico and several other Latin American countries,[44] as well as some parts of the United States and Canada, which refers specifically to this plant and its fruit. In the Southwest United States (particularly New Mexico), chile also denotes a thick, spicy, un-vinegared sauce made from this fruit, available in red and green varieties, and served over the local food, while chili denotes the meat dish. The plural is chile or chiles.

- Chilli was the original Romanization of the Náhuatl language word for the fruit (chīlli) and is the preferred British spelling according to the Oxford English Dictionary, although it also lists chile and chili as variants.[45] Chilli (and its plural chillies) is the most common spelling in Australia, India, Malaysia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Singapore and South Africa.[46][47]

The name of the plant is almost certainly unrelated to that of Chile, the country, which has an uncertain etymology perhaps relating to local place names.[48] Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico are some of the Spanish-speaking countries where chilies are known as ají, a word of Taíno origin. Though pepper originally referred to the genus Piper, not Capsicum, the latter usage is included in English dictionaries, including the Oxford English Dictionary (sense 2b of pepper) and Merriam-Webster.[49] The word pepper is also commonly used in the botanical and culinary fields in the names of different types of chili plants and their fruits.

Gallery

The habanero pepper

The habanero pepper Immature chilies in the field

Immature chilies in the field The Black Pearl cultivar

The Black Pearl cultivar Cubanelle peppers

Cubanelle peppers Scotch bonnet chili peppers in a Caribbean market

Scotch bonnet chili peppers in a Caribbean market Chili peppers drying in Kathmandu, Nepal

Chili peppers drying in Kathmandu, Nepal- Removing veins and seeds from dried chilies in San Pedro Atocpan

Dried chili pepper flakes and fresh chilies

Dried chili pepper flakes and fresh chilies- Chili pepper dip in a traditional restaurant in Amman, Jordan

Dried Thai bird's eye chilies

Dried Thai bird's eye chilies- Green chilies

Guntur chilli drying in the sun, Andhra Pradesh, India

Guntur chilli drying in the sun, Andhra Pradesh, India Sundried chilli at Imogiri, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Sundried chilli at Imogiri, Yogyakarta, Indonesia New Mexico chiles dried on the plant in Mesilla, New Mexico

New Mexico chiles dried on the plant in Mesilla, New Mexico Chili pepper wine from Virginia

Chili pepper wine from Virginia

See also

- Chili grenade, a type of weapon made with chili peppers

- Dragon's Breath (chili pepper)

- Hatch, New Mexico, known as the "Chile Capital of the World"

- History of chocolate, which the Mayans drank with ground chili peppers

- Peppersoup

- Ristra, an arrangement of dried chili pepper pods

- Sweet chili sauce, a condiment for adding a sweet, mild heat taste to food

- Taboo food and drink, which in some cultures includes chili peppers

References

- ↑ Dasgupta, Reshmi R (8 May 2011). "Indian chilli displacing jalapenos in global cuisine – The Economic Times". The Times Of India.

- ↑ "HORT410. Peppers – Notes". Purdue University Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

Common name: pepper. Latin name: Capsicum annuum L. ... Harvested organ: fruit. Fruit varies substantially in shape, pericarp thickness, color and pungency.

- ↑ Kraft, KH; Brown, CH; Nabhan, GP; Luedeling, E; Luna Ruiz, Jde J; Coppens; d'Eeckenbrugge, G; Hijmans, RJ; Gepts, P (4 December 2013). "Multiple lines of evidence for the origin of domesticated chili pepper, Capsicum annuum, in Mexico". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (17): 6165–6170. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308933111. PMC 4035960. PMID 24753581. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chili production in 2014; Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity/Chillies and Peppers, Green and Dried from pick lists". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "Birthplace of the domesticated chili pepper identified in Mexico" Eurekalert April 21, 2014

- ↑ Bosland, P.W. (1998). "Capsicums: Innovative uses of an ancient crop". In J. Janick. Progress in new crops. Arlington, VA: ASHS Press. pp. 479–487. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ↑ van Zonneveld M, Ramirez M, Williams D, Petz M, Meckelmann S, Avila T, Bejarano C, Rios L, Jäger M, Libreros D, Amaya K, Scheldeman X (2015). "Screening genetic resources of Capsicum peppers in their primary center of diversity in Bolivia and Peru". PLoS ONE. 10 (9): e0134663. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134663. PMC 4581705. PMID 26402618.

- ↑ "Chile Pepper Glossary". Thenibble.com. August 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Heiser Jr., C.B. (1976). N.W. Simmonds, ed. Evolution of Crop Plants. London: Longman. pp. 265–268.

- ↑ Eshbaugh, W.H. (1993). J. Janick and J.E. Simon, ed. New Crops. New York: Wiley. pp. 132–139.

- ↑ Collingham, Elizabeth (February 2006). Curry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-09-943786-4.

- ↑ N.Mini Raj; K.V.Peter E.V.Nybe (1 January 2007). Spices. New India Publishing. pp. 107–. ISBN 978-81-89422-44-8.

- ↑ Robinson, Simon (14 June 2007). "Chili Peppers: Global Warming". www.time.com. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Hjelmqvist, Hakon. "Cayennepeppar från Lunds medeltid". Svensk Botanisk Tidskrift, vol 89. pp. 193–.

- ↑ Myanmar Language Commission (2009). "Bagan Period". Sarkoe-Abidan: Myanmar Stone Inscriptions and Ink Writings. Yangon, Myanmar: Ministry of Education. pp. 61, 143. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ↑ Tun Nyein (trans. & ed.) (1899). "Inscriptions of Pagan, No. (16). - Obverse". Inscriptions of Pagan, Pinya, and Ava: Translations, With Notes. Rangoon, Burma: Superintendent, Government Press. p. 114. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ↑ S Kosuge, Y Inagaki, H Okumura (1961). Studies on the pungent principles of red pepper. Part VIII. On the chemical constitutions of the pungent principles. Nippon Nogei Kagaku Kaishi (J. Agric. Chem. Soc.), 35, 923–927; (en) Chem. Abstr. 1964, 60, 9827g.

- ↑ (ja) S Kosuge, Y Inagaki (1962) Studies on the pungent principles of red pepper. Part XI. Determination and contents of the two pungent

- ↑ Ruiz-Lau, Nancy; Medina-Lara, Fátima; Minero-García, Yereni; Zamudio-Moreno, Enid; Guzmán-Antonio, Adolfo; Echevarría-Machado, Ileana; Martínez-Estévez, Manuel (1 March 2011). "Water Deficit Affects the Accumulation of Capsaicinoids in Fruits of Capsicum chinense Jacq". HortScience. 46 (3): 487–492. ISSN 0018-5345.

- ↑ O'Neill, J; Brock, C; Olesen, A. E.; Andresen, T; Nilsson, M; Dickenson, A. H. (2012). "Unravelling the Mystery of Capsaicin: A Tool to Understand and Treat Pain". Pharmacological Reviews. 64 (4): 939–971. doi:10.1124/pr.112.006163. PMC 3462993. PMID 23023032.

- ↑ "History of the Scoville Scale | FAQS". Tabasco.Com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- 1 2 Tewksbury, J. J; Reagan, K. M; Machnicki, N. J; Carlo, T. A; Haak, D. C; Peñaloza, A. L; Levey, D. J (2008). "Evolutionary ecology of pungency in wild chilies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (33): 11808–11811. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802691105. PMC 2575311.

- ↑ "Chile Pepper Heat Scoville Scale". Homecooking.about.com. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ http://www.latimes.com/sns-dailymeal-1812885-pepper-x-worlds-hottest-pepper-hot-sauce-92317-20170923-story.html

- ↑ http://www.nationalgeographic.com.au/nature/the-hottest-chilli-in-the-world-was-created-in-wales-accidentally.aspx

- ↑ "Confirmed: Smokin Ed's Carolina Reaper sets new record for hottest chilli". Guinness World Records. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ↑ "Trinidad Moruga Scorpion wins hottest pepper title" Retrieved 11 May 2013

- ↑ Joshi, Monika (11 March 2012). "Chile Pepper Institute studies what's hot". Your life. USA Today. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "Aussies grow world's hottest chilli" Retrieved 12 April 2011

- ↑ "Title of world's hottest chili pepper stolen - again". The Independent. London. 25 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ Henderson, Neil (19 February 2011). ""Record-breaking" chilli is hot news". BBC News. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ↑ Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived 14 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chilies as Ornamental Plants, Seedsbydesign Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bishop's crown pepper, image, cayennediane

- ↑ Paul Rozin1 and Deborah Schiller, Paul; Schiller, Deborah (1980). "The nature and acquisition of a preference for chili pepper by humans". Motivation and Emotion. 4 (1): 77–101. doi:10.1007/BF00995932.

- ↑ Fattori, V; Hohmann, M. S.; Rossaneis, A. C.; Pinho-Ribeiro, F. A.; Verri, W. A. (2016). "Capsaicin: Current Understanding of Its Mechanisms and Therapy of Pain and Other Pre-Clinical and Clinical Uses". Molecules. 21 (7): 844. doi:10.3390/molecules21070844. PMID 27367653.

- 1 2 Haar, R. J; Iacopino, V; Ranadive, N; Weiser, S. D; Dandu, M (2017). "Health impacts of chemical irritants used for crowd control: A systematic review of the injuries and deaths caused by tear gas and pepper spray". BMC Public Health. 17 (1): 831. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4814-6. PMC 5649076. PMID 29052530.

- ↑ Mott, Maryann. "Elephant Crop Raids Foiled by Chili Peppers, Africa Project Finds". National Geographic. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Tewksbury, J. J.; Nabhan, G. P. (2001). "Directed deterrence by capsaicin in chilies". Nature. 412 (6845): 403–404. doi:10.1038/35086653. PMID 11473305.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Burruezo, A; González-Mas Mdel, C; Nuez, F (2010). "Carotenoid composition and vitamin a value in ají (Capsicum baccatum L.) and rocoto (C. Pubescens R. & P.), 2 pepper species from the Andean region". Journal of Food Science. 75 (8): S446–53. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01795.x. PMID 21535519.

- ↑ "chili" from Merriam-Webster; other spellings are listed as variants, with "Chili" identified as "chiefly British"

- ↑ The Canadian Oxford Dictionary lists chili as the main entry, and labels chile as a variant, and chilli as a British variant.

- ↑ Heiser, Charles (August 1990). Seed To Civilization: The Story of Food. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-79681-0.

- ↑ "Definition for chilli – Oxford Dictionaries Online (World English)". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ "Fall in exports crushes chilli prices in Guntur". Thehindubusinessline.com. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ "Chilli, Capsicum and Pepper are spicy plants grown for the pod. Green chilli is a culinary requirement in any Sri Lankan household". Sundaytimes.lk. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ "Chili or Pepper?". Chilipedia.org. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ↑ "va=pepper – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". M-w.com. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

External links

| Look up chili in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capsicum. |

- WildChilli.EU All about Wild Chili's / Capsicums / Peppers

- Plant Cultures: Chilli pepper botany, history and uses

- The Chile Pepper Institute of New Mexico State University

- Capsicums: Innovative Uses of an Ancient Crop

- Chilli: La especia del Nuevo Mundo (Article from Germán Octavio López Riquelme about biology, nutrition, culture and medical topics. In Spanish)

- The Hot Pepper List List of chilli pepper varieties ordered by heat rating in Scoville Heat Units (SHU)