Rockall

| |

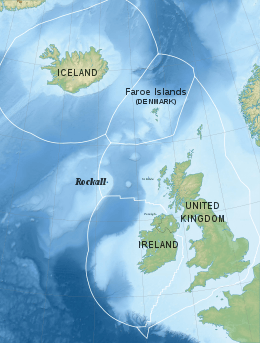

Exclusive economic zones of the UK, Ireland, Faroe Islands (Denmark), and Iceland around Rockall | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | North-east Atlantic |

| Coordinates | 57°35′46.695″N 13°41′14.308″W / 57.59630417°N 13.68730778°WCoordinates: 57°35′46.695″N 13°41′14.308″W / 57.59630417°N 13.68730778°W |

| OS grid reference | MC035165 |

| Area | 784.3 m2 (8,442 sq ft) |

| Highest elevation | 17.15 m (56.27 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Country |

|

| Council area | Na h-Eileanan Siar |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

Rockall (/ˈrɒkɔːl/) is a British uninhabited granite islet located within the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of the United Kingdom,[1][2] situated in the North Atlantic Ocean.

Its approximate distances from the closest large islands are: 301.3 kilometres (187.2 miles; 162.7 nautical miles) west of Scotland;[3] 423.2 kilometres (263.0 miles; 228.5 nautical miles) northwest of Ireland;[4] and 700 km (440 miles) south of Iceland. The nearest permanently inhabited place is North Uist, an island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, 370 km (230 miles) to the east.

The United Kingdom claimed Rockall in 1955 and incorporated it as a part of Scotland in 1972. Ireland does not recognise this claim, although it has never sought to claim sovereignty for itself.[5] The UK does not make a claim to extended EEZ based on Rockall, as it has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS); this says that "rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf".[1] However, such features are entitled to a territorial sea extending 12 nautical miles. With effect from 31 March 2014, the UK and Ireland published EEZ limits which resolved any disputes over the extent of their respective EEZs.[6][7]

In response to a Freedom of Information request in 2012, the British Government stated that, "The islet of Rockall is part of the UK: specifically it forms part of Scotland under the Island of Rockall Act 1972. No other state has disputed our claim to the islet."[1] In Scotland it is part of South Harris Parish.

Responding to a written parliamentary question in 2016, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs said: "The UK claims sovereignty over Rockall and has sought to formally annex it under its 1972 Island of Rockall Act. While Ireland has not recognised British sovereignty over Rockall, it has never sought to claim sovereignty for itself. The consistent position of successive Irish Governments has been that Rockall and similar rocks and skerries have no significance for establishing legal claims to mineral rights in the adjacent seabed or to fishing rights in the surrounding seas."[5]

Etymology

The origin and meaning of the islet's name "Rockall" is uncertain; the Old Norse name for the islet, Ròcal, may contain the element fjall, meaning "mountain".[8] It has also been suggested that the name is from the Norse *rok, meaning "foaming sea", and kollr, meaning "bald head"—a word which appears in other placenames in Scandinavian-speaking areas.[9] Another idea is that it derives from the Gaelic Sgeir Rocail, meaning "skerry of roaring" or "sea rock of roaring"[10] (although rocail can also be translated as "tearing" or "ripping").[11][12]

The Dutch mapmakers P. Plancius and C. Claesz, show an island called "Rookol" northwest of Ireland on their Map of New France and the Northern Atlantic Ocean (Amsterdam, c. 1594). The first literary reference to the island, where it is called "Rokol", is found in Martin Martin's A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland published in 1703. This book gives an account of a voyage to the archipelago of St. Kilda, and Martin states: "... and from it lies Rokol, a small rock sixty leagues to the westward of St. Kilda; the inhabitants of this place call it Rokabarra."[13]

The name Rocabarraigh, is also used in Scottish Gaelic folklore for a mythical rock which is supposed to appear three times, its last appearance being at the end of the world: "Nuair a thig Rocabarra ris, is dual gun tèid an Saoghal a sgrios." (When Rocabarra returns, the world will likely come to be destroyed.)[8]

History

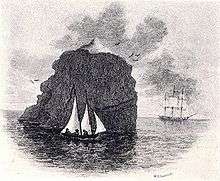

Since the late 16th century, the 17.15 metre (56.27 ft) high rock has been noted in written records.[14][15][16] In the 20th century, the location of the islet became relevant due to potential oil and fishing rights.

Lord Kennet said of it in 1971, "There can be no place more desolate, despairing and awful."[17] It gives its name to one of the sea areas named in the shipping forecast provided by the British Meteorological Office.

Rockall has been a point of interest for adventurers and amateur radio operators, who have variously landed on or briefly occupied the islet. Fewer than 20 individuals have ever been confirmed to have landed on Rockall, and the longest continuous stay by an individual was 45 days in 2014.[18] In a House of Commons debate in 1971, William Ross, MP for Kilmarnock, said: "More people have landed on the moon than have landed on Rockall."[17]

Geography

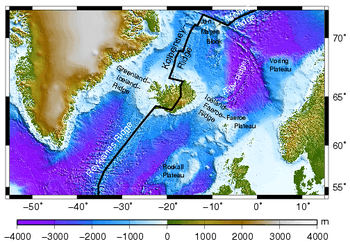

Rockall is one of the few pinnacles of the surrounding Helen's Reef; it is located 301.3 km, or 162.7 nmi west of the island of Soay, St Kilda, Scotland,[3] and 423.2 kilometres (263.0 miles; 228.5 nautical miles) northwest of Tory Island, County Donegal, Ireland.[4] Its location was precisely determined by Nick Hancock during his 2014 expedition.[19] The surrounding elevated seabed is called the Rockall Bank, lying directly south from an area known as the Rockall Plateau. It is separated from the Outer Hebrides by the Rockall Trough, itself located within the Rockall Basin (also known as the "Hatton Rockall Basin").

In 1956 the British scientist James Fisher referred to the island as "the most isolated small rock in the oceans of the world".[20] The neighbouring Hasselwood Rock and several other pinnacles of the surrounding Helen's Reef are smaller, at half the size of Rockall or less, and equally remote, but those formations are legally not islands or points on land, as they are often submerged completely, only revealed momentarily above certain types of ocean surface waves.

Rockall is about 25 metres (80 ft) wide and 31 metres (100 ft) long at its base[21] and rises sheer to a height of 17.15 m (56.27 ft).[14][15][16] It is often washed over by large storm waves, particularly in winter. There is a small ledge of 3.5 by 1.3 metres (11.5 by 4.3 ft), known as Hall's Ledge, 4 metres (13 ft) from the summit on the rock's western face.[22] It is the only named geographical location on the rock.

The nearest point on land from Rockall is 301.3 km, or 162.7 nmi, east at the uninhabited Scottish island of Soay in the St Kilda archipelago. The nearest inhabited area lies 303.2 km, or 163.7 nmi, east[23] at Hirta, the largest island in the St. Kilda group, which is populated intermittently at a single military base.[24][25] The nearest permanently inhabited settlement is 366.8 km, or 198.1 nmi, west of the headland of Aird an Rùnair,[26] near the crofting township of Hogha Gearraidh on the island of North Uist at NF705711 (57°36′33″N 7°31′7″W / 57.60917°N 7.51861°W). North Uist is part of the Na h-Eileanan Siar council area of Scotland.

The exact position of Rockall and the size and shape of the Rockall Bank was first charted in 1831 by Captain A. T. E. Vidal, a Royal Navy surveyor. The first scientific expedition to Rockall was led by Miller Christie in 1896 when the Royal Irish Academy sponsored a study of the flora and fauna.[27] They chartered the Granuaile.[20][28]

A detailed underwater mapping of the area around Rockall undertaken in 2011–2012 by Marine Scotland showed that Rockall itself is a minor pinnacle, whilst Helen's Reef extends in a sweeping arc of fissures and ridges to the north-west of the islet. Between the islet and Helen's Reef is a deeper trench much used by squid fishermen.[29]

The area where Rockall is in, is located in the pathway of the warming and moderating Gulf Stream. Although the rock does not sustain any weather station, the isolated nature of the setting dictates an extremely maritime climate without heat or cold extremes.

Geology

Rockall is made of a type of peralkaline granite that is relatively rich in sodium and potassium. Within this granite are darker bands richer in iron because they contain two iron-sodium silicate minerals called aegirine and riebeckite. The darker bands are a type of granite that geologists have named "rockallite", although use of this term is now discouraged.[31]

In 1975, a mineral new to science was discovered in a rock sample from Rockall. The mineral is called bazirite, named after the chemical elements barium and zirconium. Bazirite has the chemical composition BaZrSi3O9.[32]

Rockall forms part of the deeply eroded Rockall Igneous Centre that was formed as part of the North Atlantic Igneous Province,[33] approximately 55 million years ago, when the ancient continent of Laurasia was split apart by plate tectonics. Greenland and Europe separated and the northeast Atlantic Ocean was formed between them,[31] eventually leaving Rockall as an isolated islet.

The RV Celtic Explorer surveyed the Rockall Bank in 2003.[34] The Irish Light Vessel Granuaile (the same name as the steamer on the RIA 1896 botany survey) was chartered by the Geological Survey of Ireland, on behalf of the Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources, to conduct a seismic survey of the Rockall Bank and the Hatton Bank in July 2004,[35] as part of the Irish National Seabed Survey.[35]

Ecology

The island's only permanent macro-organism inhabitants are common periwinkles and other marine molluscs. Small numbers of seabirds, mainly fulmars, northern gannets, black-legged kittiwakes, and common guillemots, use the rock for resting in summer, and gannets and guillemots occasionally breed successfully if the summer is calm with no storm waves washing over the rock. In total there have been just over twenty species of seabird and six other animal species observed (including the aforementioned molluscs) on or near the islet.

Cold-water coral biogenic reefs have been identified on the wider Rockall Bank[36], which are contributing features for the East Rockall Bank and North-West Rockall Bank SACs[37][38].

Discovery of new species

In December 2013 surveys by Marine Scotland discovered four new species of animals in the sea around Rockall. These are believed to live in an area where hydrocarbons are released from the sea bed, known as a cold seep. The discovery has raised the issue of restricting some forms of fishery to protect the sea bed.[39] The species are:

- Volutopsius scotiae Frussen, McKay & Drewery, 2013 – a sea snail about 10 cm long

- Thyasira scotiana Zelaya, 2009 – a clam

- Isorropodon mackayi – a clam in the order Veneroida

- Antonbruunia sociabilis sp. – a marine worm in the order Phyllodocida

Visits to Rockall

The earliest recorded date of landing on the island is often given as 8 July 1810, when a Royal Navy officer named Basil Hall led a small landing party from the frigate HMS Endymion to the summit. However, research by James Fisher of the landing (see below), in the log of the Endymion and elsewhere, indicates that the actual date for this first landing was on Sunday 8 September 1811.[40]

The landing party left the Endymion for the rock by boat. Whilst there, the Endymion, which was taking depth measurements around Rockall, lost visual contact with the rock as a haze descended. The ship drifted away, leaving the landing party stranded. The expedition made a brief attempt to return to the ship, but could not find the frigate in the haze, and soon gave up and returned to Rockall. After the haze became a fog, the lookout sent to the top of Rockall spotted the ship again, but it turned away from Rockall before the expedition in their boats reached it. Finally, just before sunset, the frigate was again spotted from the top of Rockall, and the expedition was able to get back on board. The crew of the Endymion reported that they had been searching for five or six hours, firing their cannon every ten minutes. Hall related this experience and other adventures in a book entitled Fragment of Voyages and Travels Including Anecdotes of a Naval Life.

The next landing was by a Mr Johns of HMS Porcupine whilst the ship was on a mission, (between June and August 1862), to make a survey of the sea bed prior to the laying of a transatlantic telegraph cable. Johns managed to gain foothold on the island, but failed to reach the summit.

On 18 September 1955, Rockall was annexed by the British Crown when Lieutenant-Commander Desmond Scott RN, Sergeant Brian Peel RM, Corporal AA Fraser RM, and James Fisher (a civilian naturalist and former Royal Marine), were winched onto the island by a Royal Navy helicopter from HMS Vidal (coincidentally named after the man who first charted the island). The annexation of Rockall was announced by the Admiralty on 21 September 1955.

The expedition team cemented in a brass plaque on Hall's Ledge and hoisted the Union Flag to stake the UK's claim. The inscription on the plaque read:

By authority of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of her other realms and territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith, and in accordance with Her Majesty's instructions dated the 14th day of September, 1955, a landing was effected this day upon this island of Rockall from HMS Vidal. The Union flag was hoisted and possession of the island was taken in the name of Her Majesty. [Signed] R H Connell, Captain, HMS Vidal, 18 September 1955.

The initial incentive for the annexation was the test-firing of the UK's first guided nuclear weapon, the American-made Corporal missile. The missile was to be launched from South Uist and sent over the North Atlantic. The Ministry of Defence was concerned that the unclaimed island would provide an opportunity for the Soviet Union to spy on the test. Consequently, in April 1955 an order was issued to the Admiralty to seize the island and declare UK sovereignty, lest it become an outpost for foreign observers.

On 7 November 1955, J. Abrach Mackay, a member of the Clan Mackay, made a protest about the annexation; the 84-year-old local councillor declared: "My old father, God rest his soul, claimed that island for the Clan of Mackay in 1846 and I now demand that the Admiralty hand it back. It's no' theirs'." The British Government ignored the protests, which were soon forgotten.[17][41]

In 1971,[42] Captain T R Kirkpatrick RE led the landing party on a government expedition named "Operation Top Hat" that was mounted from RFA Engadine to establish that the rock was part of the United Kingdom and to prepare the islet for the installation of a light beacon. The landing party included Royal Engineers, Royal Marines and civilian members from the Institute of Geological Sciences in London. The party was landed by winch line from the Wessex 5 helicopters of the Royal Naval Air Services Commando Headquarters Squadron, commanded by Lt Cmdr Neil Foster RN. As well as collecting samples of the aegerine granite, rockallite, for later analysis in London, the top of the rock was blown off using a newly developed blasting technique, Precision Pre-Splitting. This created a level area that was drilled to take the anchorages for the light beacon that was installed the following year. There was no evidence of the brass plate thought to have been installed in 1955 and two phosphor bronze plates were chased into the wall above Hall's Ledge, each secured by four 80-tonne rock-anchor bolts.

Establishing that the rock is part of the United Kingdom and its development as a light beacon facilitated the incorporation of the island into the District of Harris in the County of Inverness in the Island of Rockall Act 1972 and reinforced the UK Government's position with regard to seabed rights in the area.

In 1978,[43] eight members of the Dangerous Sports Club, including David Kirke, one of its founders, held a cocktail party on the island.[44]

Former SAS member and survival expert (the Irish born) Tom McClean lived on the island from 26 May 1985 to 4 July 1985 to affirm the UK's claim to the islet.[45]

In 1997, the environmentalist organisation Greenpeace occupied the islet for a short time,[46] calling it Waveland, to protest against oil exploration. Greenpeace declared the island to be a "new Global State" (in this case qualifying it as a micronation) and offered citizenship to anyone willing to take their pledge of allegiance. The British Government's response was to state that "anyone is free to go there"[47] and otherwise ignore them. During his one night on Rockall, Greenpeace protester and Guardian journalist John Vidal unscrewed the 1955 plaque and re-fixed it back-to-front.[48]

In 2010, it was revealed that the plaque had gone missing. An Englishman, Andy Strangeway, announced his intention to land on the island and affix a replacement plaque in June 2010.[49] The Western Isles Council have approved planning permission for the plaque.[50] The 2010 expedition was cancelled, but Strangeway still intends to replace the plaque.[51]

In 2013 an occupation of the island by explorer Nick Hancock to raise money for the charity Help for Heroes was planned. The challenge was to land on Rockall and survive solo for 60 days.[52] On 31 May 2013, Hancock, and a TV crew from The One Show, sailed to the islet aboard the Orca III, and he made his first unsuccessful attempt to land on the islet.[53] The weather conditions at the time "were not favourable" according to a Maritime and Coastguard Agency official. Subsequently, Hancock postponed his challenge until 2014.[54] On 5 June 2014 Hancock successfully landed on Rockall to begin his 60-day survival.[55] Despite being forced to cut his 60-day goal short after losing supplies in a storm, Hancock did remain on the island for 45 days (beating McClean's occupancy record by five days).[56][57]

The "Round Rockall" sailing race, sponsored by Galway Bay Sailing Club, runs from Galway, Ireland, around Rockall and back. It was held in 2012 to coincide with the finish of the 2011–12 Volvo Ocean Race around the world.[58]

The 2015-2016 Clipper Round the World Yacht Race race 12 from New York to Londonderry was extended around Rockall despite previous promises to crew from Sir Robin Knox-Johnston that this would not happen again after the race to Danang.[59]

In 2017, the Safehaven Marine team led by Frank Kowalski set a world record for the Long Way Round Circumnavigation of Ireland via Rockall island. The Baracuda-style naval patrol, search and rescue vessel, Thunder Child, completed the route in 34 hours, 1 minute, and 47 seconds. [60] Set on an anti-clockwise direction, the new record – the first of its kind - is now subject to ratification by Irish Sailing and the Union Internationale Motonautique, the world governing board for all powerboat activity.

Ownership

United Kingdom

The UK claims Rockall along with a 12-nautical-mile (22 km; 14 mi) territorial sea around the islet inside the country's exclusive economic zone (EEZ).[1] The UK also claims "a circle of UK sovereign airspace over the islet of Rockall".[1]

The UK claimed Rockall on 18 September 1955 when "Two Royal Marines and a civilian naturalist, led by Royal Navy officer Lieutenant Commander Desmond Scott, raised a Union flag on the island and cemented a plaque into the rock".[61] Prior to this the island was legally terra nullius.[62] In 1972, the British Island of Rockall Act formally annexed Rockall to the United Kingdom.[62]

The UK considers the island administratively part of the Isle of Harris and, under the Scottish Adjacent Waters Boundaries Order 1999 a large sea area around it was declared to be under the jurisdiction of Scots law. A navigational beacon was installed on the island in 1982 and the UK declared that no ship would be allowed within a 50-mile (80 km) radius of the rock.[63] However, in 1997, the UK ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), limiting territorial sea claims to a 12-nautical-mile, or 14 mile (22 km), radius, and therefore allowing free passage in waters beyond this.

In 1988, the United Kingdom and Ireland signed an EEZ boundary agreement for which "the location of Rockall was irrelevant to the determination of the boundary".[2] In 1997, the UK ratified UNCLOS, which states that "Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf".

As the rock lies within the United Kingdom's EEZ, the UK has sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources of the area, including jurisdiction over the protection and preservation of the marine environment.[6][64]

In May 2017, declassified documents revealed that the 1955 decision to claim the island as UK territory was motivated by worries that it could otherwise be used by "hostile agents" to spy on the future South Uist missile testing range.[65]

Ireland

Potential Irish claims to Rockall are based on its proximity to the Irish mainland,[66] however the country has never formally claimed sovereignty over the rock. Although Rockall is closer to the UK coast than to the Irish coast,[3][4] Ireland does not recognise the UK's territorial claim to Rockall, "which would be the basis for a claim to a 12-mile territorial sea".[67][5]

Ireland regards Rockall as irrelevant when determining the boundaries of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) as the rock is uninhabitable[2][68][69] and in signing the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1997, the UK has agreed that "Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf".

In 1988, Ireland and the United Kingdom signed an EEZ boundary agreement, ignoring the rock per UNCLOS.[2] With effect from 31 March 2014, the UK and Ireland published EEZ limits which include Rockall within the UK's EEZ.[6][7]

In October 2012, the Irish Independent published a picture of the Irish Navy ship LÉ Róisín sailing past Rockall conducting routine maritime security patrols, and claimed that it was exercising Ireland's sovereign rights over the rock.[70]

Shipping disasters

_p0231_ROCKALL.jpg)

There have been various disasters on the neighbouring Hasselwood Rock and Helen's Reef (the latter was named in 1830).

- 1686 – a Spanish, French, or Spanish-French ship ran aground around Rockall. Several men of the crew, Spanish and French, were able to reach St. Kilda in a pinnace and save their lives. Some details of this event were recounted by Martin Martin in his A late voyage to St. Kilda, published in 1698.[13] The ship was perhaps a fishing vessel based in the Bay of Biscay and bound for North Atlantic cod fisheries.

- 1812 – a survey vessel Leonidas foundered on Helen's Reef.

- 1824 – Brigantine Helen of Dundee, bound for Quebec, foundered on Helen's Reef with fatalities.

- 1904 – Danish ship SS Norge foundered on Hasselwood Rock with the loss of nearly all its 750 passengers. This led to a proposal by D. & C. Stevenson for an unattended lightship to be moored close to the rock.[71]

In popular culture

- English poet Michael Roberts published a poem "Rockall" in his 1939 collection, Orion Marches. The poem describes a shipwrecked traveler on the rock.

- In the 1951 novel The Cruel Sea by Nicholas Monsarrat, the island features as the place of the final act of HMS Saltash's war. It is here the ship takes the surrender of two German U-boats on the last day of World War Two in Europe.

- The 1955 British landing, complete with the trappings such as the hoisting the flag, caused a certain amount of popular amusement, with some seeing it as a sort of farcical end to imperial expansion. The satirists Flanders and Swann sang a successful piece titled "Rockall", playing on the similarity of the word to the vulgar expression "fuck all", meaning "nothing": The fleet set sail for Rockall, Rockall, Rockall, To free the isle of Rockall, From fear of foreign foe. We sped across the planet, To find this lump of granite, One rather startled gannet; In fact, we found Rockall.[72]

- In The Goon Show episode "Napoleon's Piano" (October 1955), Seagoon made a less-than-triumphant landfall on Rockall with the titular piano. Rockall was the launching site for the prototype "Jet propelled guided NAAFI" in the Goon Show episode of the same name (January 1956). Musty Mind, the parody of Mastermind on the 1970s lunchtime radio programme of Noel Edmonds, featured a send-up subject, The Cultural and Social History of Rockall. And the cast of the BBC radio programme I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again claimed to have spent the break between two series of the programme making a "triumphant tour of Rockall".

- It has been suggested that Rockall is the rock which forms the setting for William Golding's 1956 novel Pincher Martin.

- The Master, a 1957 novel by T. H. White, is set inside Rockall.[73]

- David Frost, when hosting the 1960s BBC satirical TV programme That Was The Week That Was, recited a list of the dwindling British colonial possessions, ending with the words, "... and sweet Rockall."[74]

- The Irish folk group The Wolfe Tones made Rockall the subject of their 1976 song "Rock on, Rockall".[75][76]

- "Ether", the opening track of the English post-punk band Gang of Four's 1979 debut album, Entertainment!, features the satirical line "There may be oil under Rockall".

- William Sarjeant (under the pen-name Antony Swithin) wrote a series of novels titled The Perilous Quest for Lyonesse (1990-1993) set in a fictional land of Rockall, based on the island.

- A club, "The Rockall Club", has been established for people who have landed there.[77]

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Foreign & Commonwealth Office Response to Freedom of Information request regarding Rockall". 8 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Written Answers – Rockall Island. Oireachtas, Dublin, 24 March 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 Google Earth. Rockall ETRS89 57°35'46.695"N 13°41'14.308"W to Gob a' Ghaill, Soay, St Kilda at approximately WGS84 57°49'40.8"N 8°38'59.4"W is approximately 301.3 kilometres (187.2 miles; 162.7 nautical miles).

- 1 2 3 Google Earth. Rockall ETRS89 57°35'46.695"N 13°41'14.308"W to Tory Island at approximately WGS84 55°16'29.73"N 8°15'00.92"W is approximately 423.2 kilometres (263.0 miles; 228.5 nautical miles).

- 1 2 3 Written answers, Dublin: Oireachtas, retrieved January 29, 2018

- 1 2 3 "The Exclusive Economic Zone Order 2013". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Maritime Jurisdiction (Boundaries of Exclusive Economic Zone) Order 2014". irishstatutebook.ie. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- 1 2 Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012. p. 101

- ↑ Coates (1990) pp. 49–54, esp. 51-2.

- ↑ Keay and Keay (1994) p. 817.

- ↑ "Sgeir" ceantar.org. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ↑ "Rocail" ceantar.org. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- 1 2 Martin, Martin (1703). A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland Circa 1695. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- 1 2 The Rockall Club website's Facts page. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- 1 2 bbc.co.uk. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- 1 2 Stornoway Gazette. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 James Mellor (23 October 2011). "A hard place for a protest as invaders raise the flag on Rockall". The Independent.

- ↑ "The Guardian – Record occupation of Rockall". theguardian.com. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ "Nick Hancock guest blog Ordnance Survey". 9 October 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- 1 2 Fisher, James (1956). Rockall. London: Geoffrey Bles. pp. 12–13.

- ↑ MacDonald, Fraser (2006) 'The last outpost of Empire: Rockall and the Cold War" Archived 22 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine., (pdf) Journal of Historical Geography, 32 627–647. University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

- ↑ "About Rockall" Rockall2011.com. Accessed 12 December 2010

- ↑ Google Earth. Rockall ETRS89 57°35'46.695"N 13°41'14.308"W to An Campar, Hirta, St Kilda at approximately WGS84 57°49'30.4"N 8°37'03.6"W is approximately 303,195 kilometres (188,397 miles; 163,712 nautical miles).

- ↑ Maclean (1977) page 142.

- ↑ "Advice for visitors" Archived 16 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine. (2004) National Trust for Scotland. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ↑ Google Earth. Rockall ETRS89 57°35'46.695"N 13°41'14.308"W to Aird an Runair, North Uist at approximately WGS84 57°36'11.4"N 7°32'59.3"W is approximately 366,843 kilometres (227,946 miles; 198,079 nautical miles).

- ↑ "Brochure" (PDF). The Royal Irish Academy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2010 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Hamilton, John (2000) [1999]. "Granuaile – Not the Irish Lights tender." BEAM Magazine. 28. Archived from the original on 5 August 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ "Marine Scotland Information: Rockall Bathymetry 2011 and 2012". Marine Scotland. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ↑ Harvie-Brown et al (1889) Facing p. LXXXI.

- 1 2 Sutherland, D. S. (editor) (1982). Igneous Rocks of the British Isles. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 413, 541, 542. ISBN 0-471-27810-6.

- ↑ Livingstone, Alec (2002). Minerals of Scotland. National Museums of Scotland. ISBN 978-1901663464.

- ↑ Ritchie, J.D.; Gatliff, R.W.; Richards, P.C. (1999). "Early Tertiary magmatism in the offshore NW UK margin and surrounds". In Fleet A.J. & Boldy S.A.R. Petroleum geology of Northwest Europe: proceedings of the 5th conference, held at the Barbican Centre, London, 26–29 October 1997, Volume 1. London: Geological Society. p. 581. ISBN 978-1-86239-039-3. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ↑ "Irish National Seabed Survey". 2004. Archived from the original on 12 August 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- 1 2 Gray, Dermot (2004–2005). "Granuaile carries out seismic survey at Rockall" (PDF). Beam. Irish Lighthouse Service. 33: 14–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ "Marine Scotland Information: Cold Water Coral Reef". Marine Scotland. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ↑ "East Rockall Bank SAC". JNCC. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ↑ "North West Rockall Bank SAC". JNCC. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ↑ "Deep sea creatures found off Rockall 'new to science'". News Highlands and Islands. BBC. 28 December 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ↑ Fisher, James (1957). Rockall. The Country Book Club. pp. 23–35.

- ↑ Ondřej Daněk "Rockall" 2009

- ↑ "'Report on Operational Top Hat government expedition to Rockall in 1970 [sic]'" (PDF).

- ↑ "Timeline". The Rockall Club. The Rockall Club. 2015. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- ↑ Llewellyn-Smith, Julia (2004-06-06). "An endangered species". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- ↑ "Written Answers – Rockall Island". Dáil Éireann. 358. 22 May 1985. Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ SchNews issue 131 Archived 12 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine., Justice?, Brighton, 22 August 1997; see also SchNEWS Annual, Justice?, Brighton, 1998, ISBN 0-9529748-1-9

- ↑ "A hard place for a protest as invaders raise the flag on Rockall". 12 June 1997.

- ↑ John Vidal. "'Hello Mum, I'm on Rockall': The £100bn piece of rock". the Guardian.

- ↑ "Rockall bid – to erect Queen's plaque". Letterkenny Post. 25 February 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ↑ "BBC article on 2010 planning permission". BBC News. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ "Island Man News". Andy Strangeway. 20 July 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ Severin Carrell, Scotland correspondent (31 May 2013). "Rockall adventurer fails in first attempt to land on remote Atlantic islet | UK news | guardian.co.uk". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Severin Carrell, Scotland correspondent (1 June 2013). "Rockall occupation bid postponed until 2014 after weather prevents landing | UK news". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ "Ratho adventurer Nick Hancock begins Rockall solo bid". 5 June 2014.

- ↑ "Rockall". Scotland.gov.

- ↑ Nick Hancock sets world records on Rockall, Grindtv; accessed 18 July 2014.

- ↑ Round Rockall Race Archived 27 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Clippers to head for disputed Rockall to give Londonderry time to get ready for the party". www.londonderrysentinel.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ↑ "Thunderchild Route". thunderchild.safetrxapp.com. Retrieved 2017-07-06.

- ↑ BBC staff (2008). "1955: Britain claims Rockall". BBC.

- 1 2 Ian Mitchell (2012). Isles of the North. Birlinn. p. 232.

- ↑ "Rockall – The Jubilee landing and a bit of history. | heavywhalley". Heavywhalley.wordpress.com. 11 June 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ "United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Part V" (PDF). Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ↑ "UK government spy base fears over remote Rockall". BBC News. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ↑ Symmons (1993), p. 35. "As a matter of international law fall within Irish jurisdiction" and "which are closer to the Irish than the British coast"

- ↑ "Written Answers. - Ownership of Rockall". Dáil Éireann. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Tullio Treves; Laura Pineschi (1997). The Law of the Sea: The European Union and Its Member States. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 305–. ISBN 978-90-411-0326-0. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ↑ "Dáil Éireann – Volume 384 – 29 November 1988 Continental Shelf Delimitation Agreement between Ireland and Britain: Motion". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Heffernan, Breda (13 October 2012). "Our Navy's show of force off Rockall". Independent.ie.

- ↑ Talbot, Frederick A. A. (1913). Lightships and Lighthouses. pp. 299–300. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ "Flanders and Swann Online - And Then We Wrote ... - Rockall". Archived from the original on 6 October 2013.

- ↑ White, T. H., The Master: An Adventure Story (1957) J. Moulder and M. Schaefer. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ↑ http://www.frasermacdonald.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/MacDonald-F-JHG-2006.pdf

- ↑ "OWNERSHIP OF ROCKALL".

- ↑ "Why the end of the Wolfe Tones is music to my ears".

- ↑ The Rockall Club. "Home - The Rockall Club".

Bibliography

- Coates, Richard (1990) The place-names of St Kilda. Lewiston, etc.: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-077-9.

- Harvie-Brown, J. A. & Buckley, T. E. (1889) A Vertebrate Fauna of the Outer Hebrides. Edinburgh. David Douglas.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004) The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh. Canongate ISBN 1-84195-454-3

- Keay, J., and Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London. HarperCollins ISBN 0-00-255082-2

- Maclean, Charles (1977) Island on the Edge of the World: the Story of St. Kilda, Edinburgh, Canongate ISBN 0-903937-41-7

- Martin, Martin (1703) "A Voyage to St. Kilda" in A Description of The Western Islands of Scotland. Appin Regiment/Appin Historical Society. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Symmons, Clive Ralph (1993). Ireland and the law of the sea. Blackrock: Round Hall Press. ISBN 1-85800-022-X.

- Symmons, Clive Ralph (1978). The maritime zones of islands in international law. The Hague; Boston: M. Nijhoff. ISBN 9789024721719.

Further reading

- British Birds, birds breeding on Rockall. 86: 16–17, 320–321 (1993).

- Houses of the Oireachtas, Parliament of Ireland – Tithe an Oireachtais debate with the Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Dáil Éireann, 1 November 1973.

- Martin, Martin A Description of the Western isles of Scotland (1716).

External links

- Rockall.name – a complex website about the islet available in both English and Czech

- RockallIsland.co.uk – a website detailing the MSØIRC/p amateur radio expedition of 16 June 2005

- Rockall2011.com – a website advocating a charitable fund for soldiers based on a pending expedition to Rockall in 2011

- Rockall.be – a website on the MMØRAI/p amateur radio expedition to Rockall in 2011

- Waveland.org – official website of the former micronation Waveland based on Rockall

- 1955: Britain claims Rockall – "On This Day" story of British claim to Rockall from BBC's official website

- British journalist Ben Fogle attempts to claim Rockall

- Icelandic Ministry of Foreign Affairs map showing all parties' claims to the continental shelf around Rockall.

- Cross-section of the geology around Rockall