Rhizaria

| Rhizaria Temporal range: Neoproterozoic - Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ammonia tepida (Foraminifera) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Diaphoretickes |

| (unranked): | SAR |

| (unranked): | Rhizaria Cavalier-Smith, 2002 |

| Phyla | |

The Rhizaria are a species-rich supergroup of mostly unicellular[1] eukaryotes.[2] A multicellular form has also been described.[3] This supergroup was proposed by Cavalier-Smith in 2002. Being described mainly from rDNA sequences, they vary considerably in form, having no clear morphological distinctive characters (synapomorphies), but for the most part they are amoeboids with filose, reticulose, or microtubule-supported pseudopods. Many produce shells or skeletons, which may be quite complex in structure, and these make up the vast majority of protozoan fossils. Nearly all have mitochondria with tubular cristae.

Groups

The three main groups of Rhizaria are:[4]

- Cercozoa – various amoebae and flagellates, usually with filose pseudopods and common in soil

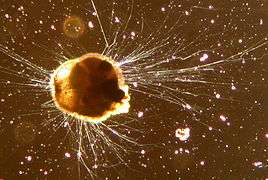

- Foraminifera – amoeboids with reticulose pseudopods, common as marine benthos

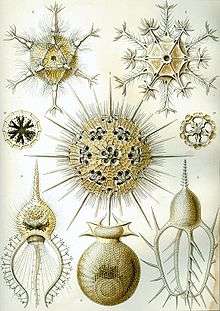

- Radiolaria – amoeboids with axopods, common as marine plankton

A few other groups may be included in the Cercozoa, but on some trees appear closer to the Foraminifera. These are the Phytomyxea and Ascetosporea, parasites of plants and animals, respectively, and the peculiar amoeba Gromia. The different groups of Rhizaria are considered close relatives based mainly on genetic similarities, and have been regarded as an extension of the Cercozoa. The name Rhizaria for the expanded group was introduced by Cavalier-Smith in 2002,[5] who also included the centrohelids and Apusozoa.

Another order that appears to belong to this taxon is the Mikrocytida.[6] These are parasites of oysters.

Evolutionary relationships

Rhizaria are part of the Diaphoretickes (bikont) clade along with Archaeplastida, Alveolata, Cryptista, Haptista, and Halvaria.

Historically, many rhizarians were considered animals because of their motility and heterotrophy. However, when a simple animal-plant dichotomy was superseded by a recognition of additional kingdoms, taxonomists generally placed rhizarians in the kingdom Protista. When scientists began examining the evolutionary relationships among eukaryotes using molecular data, it became clear that the kingdom Protista was paraphyletic. Rhizaria appear to share a common ancestor with Stramenopiles and Alveolates forming part of the SAR (Stramenopiles+Alveolates+Rhizaria) super assemblage.[7] Rhizaria has been supported by molecular phylogenetic studies as a monophyletic group.[8]

Phylogeny

Phylogeny based on Bass et al. 2009,[9] Howe et al. 2011,[10] and Silar 2016.[11]

|

|

Cercozoa |

Cercomonas sp. (Cercozoa: Cercomonadida

Cercomonas sp. (Cercozoa: Cercomonadida Ebria sp. (Cercozoa: Ebridea)

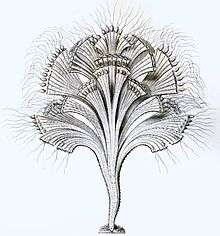

Ebria sp. (Cercozoa: Ebridea) Rhipidodendron sp. (Cercozoa: Spongomonadea)

Rhipidodendron sp. (Cercozoa: Spongomonadea) Euglypha sp. (Cercozoa: Euglyphida)

Euglypha sp. (Cercozoa: Euglyphida) Phaeodarians (Cercozoa: Phaeodarea)

Phaeodarians (Cercozoa: Phaeodarea) Clathrulina elegans (Cercozoa: Granofilosea: Desmothoracida)

Clathrulina elegans (Cercozoa: Granofilosea: Desmothoracida) Chlorarachnion sp. (Cercozoa: (Chlorarachniophyta)

Chlorarachnion sp. (Cercozoa: (Chlorarachniophyta) Vampyrella sp. (Cercozoa: Vampyrellidae)

Vampyrella sp. (Cercozoa: Vampyrellidae)_b_083.jpg)

_of_potatoes_(1914)_(14577838889).jpg) Powdery scab (Cercozoa: Plasmodiophorida)

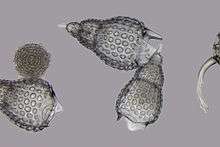

Powdery scab (Cercozoa: Plasmodiophorida) Foraminiferans (Retaria: Foraminifera)

Foraminiferans (Retaria: Foraminifera) Polycystines (Retaria: Radiolaria)

Polycystines (Retaria: Radiolaria) Acantharians (Retaria: Radiolaria)

Acantharians (Retaria: Radiolaria)

References

- ↑ Christopher Taylor (2004). "Rhizaria". Archived from the original on 2009-04-20.

- ↑ Nikolaev SI, Berney C, Fahrni JF, et al. (May 2004). "The twilight of Heliozoa and rise of Rhizaria, an emerging supergroup of amoeboid eukaryotes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (21): 8066–71. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308602101. PMC 419558. PMID 15148395.

- ↑ Brown; et al. (2012). "Aggregative Multicellularity Evolved Independently in the Eukaryotic Supergroup Rhizaria". Current Biology. 22: 1123–1127. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.021. PMID 22608512.

- ↑ Moreira D, von der Heyden S, Bass D, López-García P, Chao E, Cavalier-Smith T (July 2007). "Global eukaryote phylogeny: Combined small- and large-subunit ribosomal DNA trees support monophyly of Rhizaria, Retaria and Excavata". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 44 (1): 255–66. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.11.001. PMID 17174576.

- ↑ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2002). "The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 52 (2): 297–354. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-2-297. ISSN 1466-5026. PMID 11931142. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ↑ Hartikainen, H; Stentiford, GD; Bateman, KS; Berney, C; Feist, SW; Longshaw, M; Okamura, B; Stone, D; Ward, G; Wood, C; Bass, D (2014). "Mikrocytids are a broadly distributed and divergent radiation of parasites in aquatic invertebrates". Curr Biol. 24 (7): 807–12. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.033. PMID 24656829.

- ↑ Burki, F; Shalchian-Tabrizi, K; Minge, M; Skjaeveland, A; Nikolaev, SI; Jakobsen, KS; Pawlowski, J (2007). Butler, Geraldine, ed. "Phylogenomics Reshuffles the Eukaryotic Supergroups". PLoS ONE. 2 (8): e790–. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000790. PMC 1949142. PMID 17726520. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ↑ Burki, Fabien; Shalchian-Tabrizi, Kamran; Pawlowski, Jan (August 23, 2008). "Phylogenomics reveals a new 'megagroup' including most photosynthetic eukaryotes". Biology Letters. 4 (4): 366–9. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0224. PMC 2610160. PMID 18522922. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Bass D, Chao EE, Nikolaev S, et al. (February 2009). "Phylogeny of Novel Naked Filose and Reticulose Cercozoa: Granofilosea cl. n. and Proteomyxidea Revised". Protist. 160 (1): 75–109. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2008.07.002. PMID 18952499.

- ↑ Howe; et al. (2011), "Novel Cultured Protists Identify Deep-branching Environmental DNA Clades of Cercozoa: New Genera Tremula, Micrometopion, Minimassisteria, Nudifila, Peregrinia", Protist, 162: 332–372, doi:10.1016/j.protis.2010.10.002, PMID 21295519

- ↑ Silar, Philippe (2016), "Protistes Eucaryotes: Origine, Evolution et Biologie des Microbes Eucaryotes", HAL archives-ouvertes: 1–462