McLane–Ocampo Treaty

The McLane–Ocampo Treaty, formally the Treaty of Transit and Commerce, was an 1859 agreement negotiated between the United States and Mexico, during Mexico's War of the Reform, when the Mexican liberal government of Benito Juárez was fighting against conservatives. The treaty was controversial in both Mexico and the United States. For Mexico, it was seen as a betrayal of the country by ceding rights to the United States, which had defeated Mexico in the Mexican–American War a decade before, but it promised the financially-strapped liberal government the means to wage war against conservatives. The U.S. Senate rejected ratification of the treaty in 1860. Had it been ratified, it would have given major control over Mexican territory seen as a crucial transit point from the Caribbean to the Pacific Ocean.[1]

Background

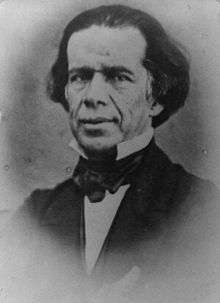

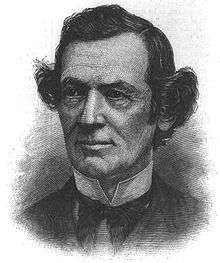

The treaty was negotiated by Robert M. McLane, the US Ambassador to Mexico, and Melchor Ocampo, Mexico's Minister of Foreign Affairs.[2] It was signed in the port of Veracruz in Mexico on December 14, 1859, which would have sold the perpetual right of transit to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec to the U.S. for $4 million through the Mexican ports of Tehuantepec in the south, to Coatzacoalcos in the Gulf of Mexico free of any charge or duty, for military and commercial effects and troops. It even required Mexican troops to assist in the enforcement of the rights permanently granted to the U.S.

Additionally, it granted perpetual rights of passage through two strings of Mexican land: one that would run through the state of Sonora from the port of Guaymas on the Gulf of California, to Nogales, on the border with Arizona; and another one from the western port of Mazatlán, in the state of Sinaloa, going through Monterrey all the way through Matamoros, Tamaulipas, south of present-day Brownsville, Texas, on the Gulf of Mexico. Mexico was also compelled to build storage facilities on either side of the Tehuantepec isthmus.

Of the $4 million for the total cost of these benefits, the U.S. would pay immediately $2 million to the Mexican government, and the rest would stay in U.S. hands in provision for payments to American citizens suing the Mexican government for damages to their rights.

Although U.S. President James Buchanan strongly favored the arrangement, and Mexican President Benito Juárez badly needed the money to finance the war that he was waging against the Conservative Party, the treaty was never ratified by the U.S. Senate because of the imminent civil war in the U.S., whose the northern, free states were concerned that the provisions in the treaty, in particular the free transit of military effects and troops through the isthmus would benefit the soon-to-become Confederate States if there was an open civil war.

The U.S. hoped to build a railroad or canal across the isthmus to speed transport of mail and trade goods between the eastern and western coasts. Roads there and in Nicaragua and Panama already carried considerable traffic.

Treaty provisions

- Extending the Gadsden Treaty, Mexico agreed to grant the US a right "in perpetuity" to transit across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

- Both parties agreed to protect the region's trade routes

- Mexico agreed to establish "ports of deposit" at both coasts

- Goods in transit from port to port would be subject to no tariff or duty

- Goods imported to Mexico at these ports would be subject to normal tariffs

- Mexico agreed to grant the US the right to intervene at the request of Mexico, or in emergencies without, in the case of danger to the trade routes

- Mexico agreed to grant the US the right of military transit, with due notice

- Mexico agreed to grant US citizens the right of transit across Mexico by various routes

- Both parties agreed to reciprocal and equal tariff policies

- Mexico agreed not to grant other parties similar rights

Legacy in Mexico

For Mexicans who consider President Benito Juárez a nationalist hero who defended the nation's sovereignty against the French Intervention in Mexico, the McLane-Ocampo Treaty gives fuel to Juárez's critics who see him as not being so ideologically pure. Juárez authorized U.S. ships to attack Mexican conservative vessels in 1860, prompting critics' charges that Juárez "condoned foreign intervention and sold out to the United States."[3] In the U.S. the unratified treaty garners little attention from scholars, but in Mexico it is the subject of major studies.[4][5]

See also

References

- ↑ Charles R. Berry, "McLane-Ocampo Treaty (1859)" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 3, p. 561. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ↑ Edward J. Berbusse, "The Origins of the McLane-Ocampo Treaty of 1859." The Americas vol. 14 (1958): 223–243.

- ↑ D.F. Stevens, "Benito Juárez" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 3. p. 334. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ↑ Agustín Cue Canovas, Agustín, El tratado McLane-Ocampo: Juárez, los Estados Unitods y Europa. 2nd ed. 1959.

- ↑ Salvador Ysunza Uzeta, Juárez y el tratado McLane-Ocampo. 1964.

Further reading

- Berbusse, Edward J. "The Origins of the McLane-Ocampo Treaty of 1859," The Americas vol. 14 (1958): 223–243.

- Cue Canovas, Agustín, El tratado McLane-Ocampo: Juárez, los Estados Unitods y Europa. 2nd ed. 1959.

- Ysunza Uzeta, Salvador. Juárez y el tratado McLane-Ocampo. 1964.

External links

- Mexican-American relations were a primary topic of the 1860 State of the Union address by Buchanan.