Red wolf

| Red wolf | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Red wolf showing typical coloration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. rufus |

| Binomial name | |

| Canis rufus | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

The red wolf (Canis lupus rufus[6][4] or Canis rufus[7]) also known as the Florida black wolf or Mississippi Valley wolf,[8] is a canid native to the southeastern United States of unresolved taxonomic identity.[9][10] Morphologically it is intermediate between the coyote and gray wolf, and is of a reddish, tawny color.[11][12] The Red Wolf is a federally listed endangered species of the United States and is protected by law.[13] It has been listed by IUCN as a critically endangered species since 1996.[2] It is considered the rarest species of wolf and is one of the five most endangered species of canid in the world.[14]

Red wolves may have been the first New World wolf species encountered by European colonists, and were originally distributed throughout the eastern United States from the Atlantic Ocean to central Texas, and in the north from the Ohio River Valley, northern Pennsylvania and southern New York south to the Gulf of Mexico.[10] The red wolf was nearly driven to extinction by the mid-1900s due to aggressive predator-control programs, habitat destruction, and extensive hybridization with coyotes. By the late 1960s, it occurred in small numbers in the Gulf Coast of western Louisiana and eastern Texas. Fourteen of these survivors were selected to be the founders of a captive-bred population, which was established in the Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium between 1974 and 1980. After a successful experimental relocation to Bulls Island off the coast of South Carolina in 1978, the red wolf was declared extinct in the wild in 1980 to proceed with restoration efforts. In 1987, the captive animals were released into the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge on the Albemarle Peninsula in North Carolina, with a second release, since reversed, taking place two years later in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.[15] Of 63 red wolves released from 1987–1994,[16] the population rose to as many as 100–120 individuals in 2012, but has declined to 40 individuals in 2018.[17]

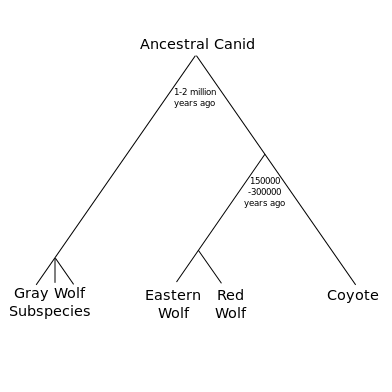

The red wolf's taxonomic status is the subject of ongoing debate. Genetic studies provide two theories about wolves in North America. The first theory proposes that there exists only two-species - grey wolves (C. lupus) and (western) coyotes (Canis latrans). These produced hybrids, including the Great Lakes wolf, the eastern coyote, the eastern wolf, and the red wolf. The second theory proposes that there exists three species – the addition of the eastern wolf as the species C. lycaon, with the red wolf being the same species. Hybrids include the Great Lakes wolf that are the product of grey wolf × eastern wolf hybridization, and eastern coyotes that are the result of eastern wolf × western coyote hybridization.[18] However, based on morphology the red wolf is considered as the separate species Canis rufus,[7] with possible fossils dating back to 10,000 years ago.[1] The debate remains unresolved.

Taxonomy

The taxonomic status of the red wolf is debated. It has been described as either a species with a distinct lineage,[19] a recent hybrid of the gray wolf and the coyote,[4] an ancient hybrid of the gray wolf and the coyote which warrants species status,[20] or a distinct species that has undergone recent hybridization with the coyote.[21][22]

The naturalists John James Audubon and John Bachman were the first to suggest that the wolves of the southern United States were different from wolves in its other regions. In 1851 they recorded the "Black American Wolf" as C. l. var arer that existed in Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, southern Indiana, southern Missouri, Louisiana, and northern Texas. They also recorded the "Red Texan Wolf" as C. l. var rufus that existed from northern Arkansas, through Texas, and into Mexico. In 1912 the zoologist Gerrit Smith Miller Jr. noted that the designation arer was unavailable and recorded these wolves as C. l. floridanus.[23]

In 1937 the zoologist Edward Alphonso Goldman proposed a new species of wolf Canis rufus.[7] Three subspecies of red wolf were originally recognized by Goldman with two of these subspecies now being extinct. The Florida black wolf (Canis rufus floridanus) (Maine to Florida) has been extinct since 1908 and Gregory's wolf (Canis rufus gregoryi) (south-central United States)[1] was declared functionally extinct in the wild by 1980. The Texas red wolf (Canis rufus rufus) was also functionally extinct in the wild by 1980, although that status was changed to endangered when captive-bred red wolves from Texas were reintroduced in eastern North Carolina in 1987.[24]

In 1967, the zoologists Barbara Lawrence and William H. Bossert believed that the case for classifying C. rufus as a species was based too heavily on the small red wolves of central Texas, from where it was known that there existed hybridization with the coyote. They said that if an adequate number of specimens had have been included from Florida, then the separation of C. rufus from C. lupus would have been unlikely.[23] The taxonomic reference Catalogue of Life classifies the red wolf as a subspecies of Canis lupus.[6] The mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft, writing in Mammal Species of the World (2005), regards the red wolf as a hybrid of the gray wolf and the coyote, but due to its uncertain status compromised by recognizing it as a subspecies of the grey wolf Canis lupus rufus.[4]

Taxonomic debate

When European settlers first arrived to North America, the coyote's range was limited to the western half of the continent. They existed in the arid areas and across the open plains, including the prairie regions of the midwestern states. Early explorers found some in Indiana and Wisconsin. From the mid-1800s coyotes began expanding beyond their original range.[23]

The taxonomic debate regarding North American wolves can be summarised as follows:

There are two prevailing evolutionary models for North American Canis: (i) a two-species model that identifies grey wolves (C. lupus) and (western) coyotes (Canis latrans) as distinct species that gave rise to various hybrids, including the Great Lakes-boreal wolf (also known as Great Lakes wolf), the eastern coyote (also known as Coywolf/brush wolf/tweed wolf), the red wolf and the eastern wolf; and (ii) a three-species model that identifies the grey wolf, western coyote and eastern wolf (C. lycaon) as distinct species, where Great Lakes-boreal wolves are the product of grey wolf × eastern wolf hybridization, eastern coyotes are the result of eastern wolf × western coyote hybridization, and red wolves are considered historically the same species as the eastern wolf, although their contemporary genetic signature has diverged owing to a bottleneck associated with captive breeding.[18]

Fossil evidence

The paleontologist Ronald M. Nowak notes that the oldest fossil remains of the red wolf are 10,000 years old and were found in Florida near Melbourne, Brevard County, Withlacoochee River, Citrus County, and Devil's Den Cave, Levy County. He notes that there are only a few, but questionable, fossil remains of the gray wolf found in the southeastern states. He proposes that following the extinction of the dire wolf, the coyote appears to have been displaced from the southeast of the US by the red wolf until last century, when the extirpation of wolves allowed the coyote to expand its range. He also proposes that the ancestor of all North American and Eurasian wolves was C. mosbachensis, which lived in the Middle Pleistocene 700,000–300,000 years ago.[1] C. mosbachensis was a wolf that once lived across Eurasia before going extinct. It was smaller than most North American wolf populations and smaller than C. rufus, and has been described as being similar in size to the small Indian wolf, Canis lupus pallipes. He further proposes that C. mosbachensis invaded North America where it became isolated by the later glaciation and there gave rise to C. rufus. In Eurasia, C. mosbachensis evolved into C. lupus, which later invaded North America.[19]:242

The paleontologist and expert on genus Canis natural history, Xiaoming Wang, looked at red wolf fossil material but could not state if it was, or was not, a separate species. He said that R. Nowak had put together more morphometric data on red wolves than anybody else, but Nowak's statistical analysis of the data revealed a red wolf that is difficult to deal with. Wang believes that studies of ancient DNA taken from fossils might help settle the debate.[25]

Morphological evidence

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_C._lupus%2C_rufus_%26_latrans.jpg)

In 1771 the English naturalist Mark Catesby referred to Florida and the Carolinas when he wrote that "The Wolves in America are like those of Europe, in shape and colour, but are somewhat smaller." They were described as being more timid and less voracious.[26] In 1791 the American naturalist William Bartram wrote in his book Travels about a wolf which he had encountered in Florida that was larger than a dog, but was black in contrast to the larger yellow-brown wolves of Pennsylvania and Canada.[27][28] In 1851 the naturalists John James Audubon and John Bachman described the "Red Texan Wolf" in detail. They noted that it could be found in Florida and other southeastern states, but it differed from other North American wolves and named it Canis lupus rufus. It was described as being more fox-like than the gray wolf, but retaining the same "sneaking, cowardly, yet ferocious disposition".[3]

In 1905 the mammologist Vernon Bailey referred to the "Texan Red Wolf" with the first use of the name Canis rufus.[29] In 1937 the zoologist Edward Goldman undertook a morphological study of southeastern wolf specimens. He noted that their skulls and dentition differed from those of gray wolves and closely approached those of coyotes. He identified the specimens as all belonging to the one species which he referred to as Canis rufus.[7][30] Goldman then examined a large number of southeastern wolf specimens and identified three subspecies, noting that their colors ranged from black, gray, and cinnamon-buff.[30]

It is difficult to distinguish the red wolf from a red wolf × coyote hybrid.[28] During the 1960s, two studies of the skull morphology of wild Canis in the southeastern states found them to belong to the red wolf, the coyote, or many variations in between. The conclusion was that there has been recent massive hybridization with the coyote.[31][32] In contrast, another 1960s study of Canis morphology concluded that the red wolf, eastern wolf, and domestic dog were closer to the gray wolf than the coyote, while still remaining clearly distinctive from each other. The study regarded these 3 canines as subspecies of the gray wolf. However, the study noted that "red wolf" specimens taken from the edge of their range which they shared with the coyote could not be attributed to any one species because the cranial variation was very wide. The study proposed further research to ascertain if hybridization had occurred.[33][34]

In 1971, a study of the skulls of C. rufus, C. lupus and C. latrans indicated that C. rufus was distinguishable by being in size and shape midway between the gray wolf and the coyote. A re-examination of museum canine skulls collected from central Texas between 1915-1918 showed variations spanning from C. rufus through to C. latrans. The study proposes that by 1930 due to human habitat modification, the red wolf had disappeared from this region and had been replaced by a hybrid swarm. By 1969, this hybrid swarm was moving eastwards into eastern Texas and Louisiana.[35]

In the late 19th Century, sheep farmers in Kerr County, Texas stated that the coyotes in the region were larger than normal coyotes, and they believed that they were a gray wolf and coyote cross.[23] In 1970, the wolf mammalogist L. David Mech proposed that the red wolf was a hybrid of the gray wolf and coyote, and suggested that it should be taxonomically recognized as C. lupus × C. latrans.[5] However, a 1971 study compared the cerebellum within the brain of 6 Canis species and found that the cerebellum of the red wolf indicated a distinct species, was closest to that of the gray wolf, but in contrast indicated some characteristics that were more primitive than those found in any of the other Canis species.[36] In 2014, a three dimensional morphometrics study of Canis species accepted only 6 red wolf specimens for analysis from those on offer due to the impact of hybridization on the others.[21]

DNA evidence

Different DNA studies may give conflicting results because of the specimens selected, the technology used, and the assumptions made by the researchers.[37] Any one from a panel of genetic markers can be chosen for use in a study. The techniques used to extract, locate and compare genetic sequences can be applied using advances in technology, which allows researchers to observe longer lengths of base pairs that provide more data to give better phylogenetic resolution.[38] Phylogenetic trees compiled using different genetic markers have given conflicting results on the relationship between the wolf, dog and coyote. One study based on SNPs[39] (a single mutation), and another based on nuclear gene sequences[40] (taken from the cell nucleus), showed dogs clustering with coyotes and separate from wolves. Another study based on SNPS showed wolves clustering with coyotes and separate from dogs.[41] Other studies based on a number of markers show the more widely accepted result of wolves clustering with dogs separate from coyotes.[42][43] These results demonstrate that caution is needed when interpreting the results provided by genetic markers.[39]

Genetic evidence

In 1980, a study used gel electrophoresis to look at fragments of DNA taken from dogs, coyotes, and wolves from the red wolf's core range. The study found that a unique allele (expression of a gene) associated with Lactate dehydrogenase could be found in red wolves but not dogs and coyotes. The study suggests that this allele survives in the red wolf. The study did not compare gray wolves for the existence of this allele.[44]

Mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) passes along the maternal line and can date back thousands of years.[25] In 1991, a study of red wolf mDNA indicates that red wolf genotypes match those known to belong to the gray wolf or the coyote. The study concluded that the red wolf is either a wolf × coyote hybrid or a species that has hybridized with the wolf and coyote across its entire range. The study proposed that the red wolf is a south-eastern occurring subspecies of the gray wolf that has undergone hybridization due to an expanding coyote population, however being unique and threatened that it should remain protected.[45] This conclusion led to debate for the remainder of the decade.[46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56]

In 2000, a study looked at red wolves and eastern Canadian wolves. The study agreed that these two wolves readily hybridize with the coyote. The study used 8 microsatellites (genetic markers taken from across the genome of a specimen). The phylogenetic tree produced from the genetic sequences showed red wolves and eastern Canadian wolves clustering together. These then clustered next closer with the coyote and away from the gray wolf. A further analysis using mDNA sequences indicated the presence of coyote in both of these two wolves, and that these two wolves had diverged from the coyote 150,000–300,000 years ago. No gray wolf sequences were detected in the samples. The study proposes that these findings are inconsistent with the two wolves being subspecies of the gray wolf, that red wolves and eastern Canadian wolves evolved in North America after having diverged from the coyote, and therefore they are more likely to hybridize with coyotes.[57] In 2009, a study of eastern Canadian wolves using microsatellites, mDNA, and the paternally-inherited yDNA markers found that the eastern Canadian wolf was a unique ecotype of the gray wolf that had undergone recent hybridization with other gray wolves and coyotes. It could find no evidence to support the findings of the earlier 2000 study regarding the eastern Canadian wolf. The study did not include the red wolf.[58]

In 2011, a study compared the genetic sequences of 48,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (mutations) taken from the genomes of canids from around the world. The comparison indicated that the red wolf was about 76% coyote and 24% gray wolf with hybridization having occurred 287–430 years ago. The eastern wolf was 58% gray wolf and 42% coyote with hybridization having occurred 546–963 years ago. The study rejected the theory of a common ancestry for the red and eastern wolves.[59][25]

Also in 2011, a scientific literature review was undertaken to help assess the taxonomy of North American wolves. One of the findings proposed was that the eastern wolf is supported as a separate species by morphological and genetic data. Genetic data supports a close relationship between the eastern and red wolves, but not close enough to support these as one species. It was "likely" that these were the separate descendants of a common ancestor shared with coyotes. This review was published in 2012.[60] In 2014, the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis was invited by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to provide an independent review of its proposed rule relating to gray wolves. The Center's panel findings were that the proposed rule was heavily dependent upon the analysis contained in a scientific literature review conducted in 2011 (Chambers et al.), that this work was not universally accepted and that the issue was "not settled", and that the rule does not represent the "best available science".[61]

In early 2016, an mDNA analysis of 3 ancient (300–1900 years old) wolf-like samples from the south-eastern United States found that they grouped with the coyote clade, although their teeth were wolf-like. The study proposed that the specimens were either coyotes and this would mean that coyotes had occupied this region continuously rather than intermittently, a North American evolved red wolf lineage related to coyotes, or an ancient coyote–wolf hybrid. Ancient hybridization between wolves and coyotes would likely have been due to natural events or early human activities, not landscape changes associated with European colonization because of the age of these samples.[62] Coyote–wolf hybrids may have occupied the southeastern United States for a long time, filling an important niche as a large predator.[53][62]

Genomic evidence

.png)

In July 2016, a whole-genome DNA study proposed, based on the assumptions made, that all of the North American wolves and coyotes diverged from a common ancestor less than 6,000–117,000 years ago. The study also indicated that all North America wolves have a significant amount of coyote ancestry and all coyotes some degree of wolf ancestry, and that the red wolf and Great Lakes region wolf are highly admixed with different proportions of gray wolf and coyote ancestry. One test indicated a wolf/coyote divergence time of 51,000 years before present that matched other studies indicating that the extant wolf came into being around this time. Another test indicated that the red wolf diverged from the coyote between 55,000–117,000 years before present and the Great Lakes region wolf 32,000 years before present. Other tests and modelling showed various divergence ranges and the conclusion was a range of less than 6,000 and 117,000 years before present. The study found that coyote ancestry was highest in red wolves from the southeast of the United States and lowest among the Great Lakes region wolves.

The theory proposed was that this pattern matched the south-to-north disappearance of the wolf due to European colonization and its resulting loss of habitat. Bounties led to the extirpation of wolves initially in the southeast, and as the wolf population declined wolf-coyote admixture increased. Later, this process occurred in the Great Lakes region with the influx of coyotes replacing wolves, followed by the expansion of coyotes and their hybrids across the wider region.[63][64] The red wolf may possess some genomic elements that were unique to gray wolf and coyote lineages from the American South.[63] The proposed timing of the wolf/coyote divergence conflicts with the finding of a coyote-like specimen in strata dated to 1 million years before present,[65] and red wolf fossil specimens dating back 10,000 years ago.[1] The study concluded by stating that because of the extirpation of gray wolves in the American Southeast, "the reintroduced population of red wolves in eastern North Carolina is doomed to genetic swamping by coyotes without the extensive management of hybrids as is currently practiced by the USFWS."[63]

In September 2016, the USFWS announced a program of changes to the red wolf recovery program[66] and "will begin implementing a series of actions based on the best and latest scientific information". The service will secure the captive population which is regarded as not sustainable, determine new sites for additional experimental wild populations, revise the application of the existing experimental population rule in North Carolina, and complete a comprehensive Species Status Assessment.[67]

In 2017 a group of canid researchers challenged the recent finding that the red wolf and the eastern wolf were the result of recent coyote-wolf hybridization. The group highlight that no testing had been undertaken to ascertain the time period that hybridization had occurred and that, by the previous study's own figures, the hybridization could not have occurred recently but supports a much more ancient hybridization. The group found deficiencies in the previous study's selection of specimens and the findings drawn from the different techniques used. Therefore, the group argues that both the red wolf and the eastern wolf remain genetically distinct North American taxa.[20] This was rebutted by the authors of the earlier study.[68]

Physical description and behavior

The red wolf's appearance is typical of the genus Canis, and is generally intermediate in size between the coyote and gray wolf, though some specimens may overlap in size with small gray wolves. A study of Canis morphometrics conducted in eastern North Carolina reported that red wolves are morphometrically distinct from coyotes and hybrids.[69] Adults measure 136–160 cm (53.5–63 in) in length, and weigh 23–39 kg (50-85 lbs).[69] Its pelage is typically more reddish and sparsely furred than the coyote's and gray wolf's, though melanistic individuals do occur.[11] Its fur is generally tawny to grayish in color, with light markings around the lips and eyes.[12] Like the eastern wolf,[70] the red wolf has been compared by some authors to the greyhound in general form, owing to its relatively long and slender limbs. The ears are also proportionately larger than the coyote's and gray wolf's. The skull is typically narrow, with a long and slender rostrum, a small braincase and a well developed sagittal crest. Its cerebellum is unlike that of other Canis species, being closer in form to that of canids of the Vulpes and Urocyon genera, thus indicating that the red wolf is one of the more plesiomorphic members of its genus.[11]

The red wolf is more sociable than the coyote, but less so than the gray wolf. It mates in January–February, with an average of 6-7 pups being born in March, April, and May. It is monogamous, with both parents participating the rearing of young.[71][72] Denning sites include hollow tree trunks, along stream banks and the abandoned earths of other animals. By the age of six weeks, the pups distance themselves from the den,[71] and reach full size at the age of one year, becoming sexually mature two years later.[12]

Using long-term data on red wolf individuals of known pedigree, it was found that inbreeding among first-degree relatives was rare.[73] A likely mechanism for avoidance of inbreeding is independent dispersal trajectories from the natal pack. Many of the young wolves spend time alone or in small non-breeding packs composed of unrelated individuals. The union of two unrelated individuals in a new home range is the predominant pattern of breeding pair formation.[73] Inbreeding is avoided because it results in progeny with reduced fitness (inbreeding depression) that is predominantly caused by the homozygous expression of recessive deleterious alleles.[74]

Prior to its extinction in the wild, the red wolf's diet consisted of rabbits, rodents, and nutria (an introduced species).[75] In contrast, the red wolves from the restored population rely on white-tailed deer, raccoon, nutria and rabbits.[76][77] It should be noted, however, that white-tailed deer were largely absent from the last wild refuge of red wolves on the Gulf Coast between Texas and Louisiana (where specimens were trapped from the last wild population for captive breeding), which likely accounts for the discrepancy in their dietary habits listed here. Historical accounts of wolves in the southeast by early explorers such as William Hilton, who sailed along the Cape Fear River in what is now North Carolina in 1644, also note that they ate deer.[78]

Range and habitat

.png)

The originally recognized red wolf range extended throughout the southeastern United States from the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, north to the Ohio River Valley and central Pennsylvania, and west to Central Texas and southeastern Missouri.[79] Research into paleontological, archaeological and historical specimens of red wolves by Ronald Nowak expanded their known range to include land south of the Saint Lawrence River in Canada, along the eastern seaboard, and west to Missouri and mid-Illinois, terminating in the southern latitudes of Central Texas.[1]

Since 1987, red wolves have been released into northeastern North Carolina, where they roam 1.7 million acres.[80] These lands span five counties (Dare, Hyde, Tyrrell, Washington, and Beaufort) and include three national wildlife refuges, a U.S. Air Force bombing range, and private land.[80] The red wolf recovery program is unique for a large carnivore reintroduction in that more than half of the land used for reintroduction lies on private property. Approximately 680,000 acres (2,800 km2) are federal and state lands, and 1,002,000 acres (4,050 km2) are private lands. Beginning in 1991, red wolves were also released into the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in eastern Tennessee.[81] However, due to exposure to environmental disease (parvovirus), parasites, and competition (with coyotes as well as intraspecific aggression), the red wolf was unable to successfully establish a wild population in the park. Low prey density was also a problem, forcing the wolves to leave the park boundaries in pursuit of food in lower elevations. In 1998, the FWS removed the remaining red wolves in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, relocating them to Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in eastern North Carolina.[82] Other red wolves have been released on the coastal islands in Florida, Mississippi, and South Carolina as part of the captive breeding management plan. St. Vincent Island in Florida is currently the only active island propagation site.

Given their wide historical distribution, red wolves probably used a large suite of habitat types at one time. The last naturally occurring population used coastal prairie marshes, swamps, and agricultural fields used to grow rice and cotton. However, this environment probably does not typify preferred red wolf habitat. Some evidence shows the species was found in highest numbers in the once extensive bottom-land river forests and swamps of the southeastern United States. Red wolves reintroduced into northeastern North Carolina have used habitat types ranging from agricultural lands to forest/wetland mosaics characterized by an overstory of pine and an understory of evergreen shrubs. This suggests that red wolves are habitat generalists and can thrive in most settings where prey populations are adequate and persecution by humans is slight.[28]

Extirpation in the wild

_Louisiana_black_wolf.png)

Before the arrival of Europeans, the red wolf featured prominently in Cherokee mythology, where it is known as wa'ya (ᏩᏯ), said to be the companion of Kana'ti the hunter and father of the Aniwaya or Wolf Clan.[83] Cherokees generally avoided killing red wolves, as such an act was believed to bring about the vengeance of the killed animals' pack-mates.[84]

In 1940 the biologist Stanley P. Young noted that the red wolf was still common in eastern Texas, where more than 800 had been caught in 1939 because of their attacks on livestock. He did not believe that they could be exterminated because of their habit of living concealed in thickets.[85] In 1962 a study of skull morphology of wild Canis in the states of Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas indicated that the red wolf existed in only a few populations due to hybridization with the coyote. The explanation was that either the red wolf could not adapt to changes to its environment due to human land-use along with its accompanying influx of competing coyotes from the west, or that the red wolf was being hybridized out of existence by the coyote.[31]

Captive breeding and reintroduction

After the passage of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, formal efforts backed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began to save the red wolf from extinction, when a captive-breeding program was established at the Point Defiance Zoological Gardens, Tacoma, Washington. Four hundred animals were captured from southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas from 1973 to 1980 by the USFWS.[86][87] Measurements, vocalization analyses, and skull X-rays were used to distinguish red wolves from coyotes and red wolf-coyote hybrids. Of the 400 animals captured, only 43 were believed to be red wolves and sent to the breeding facility. The first litters were produced in captivity in May 1977. Some of the pups were determined to be hybrids, and they and their parents were removed from the program. Of the original 43 animals, only 17 were considered pure red wolves and since three were unable to breed, 14 became the breeding stock for the captive-breeding program.[88] These 14 were so closely related that they had the genetic effect of being only eight individuals.

In December 1976, two wolves were released onto Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge's Bulls Island in South Carolina with the intent of testing and honing reintroduction methods. They were not released with the intent of beginning a permanent population on the island.[89] The first experimental translocation lasted for 11 days, during which a mated pair of red wolves was monitored day and night with remote telemetry. A second experimental translocation was tried in 1978 with a different mated pair, and they were allowed to remain on the island for close to nine months.[89] After that, a larger project was executed in 1987 to reintroduce a permanent population of red wolves back to the wild in the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge (ARNWR) on the eastern coast of North Carolina. Also in 1987, Bulls Island became the first island breeding site. Pups were raised on the island and relocated to North Carolina until 2005.[90]

In September 1987, four male-female pairs of red wolves were released in ARNWR in northeastern North Carolina and designated as an experimental population. Since then, the experimental population has grown and the recovery area expanded to include four national wildlife refuges, a Department of Defense bombing range, state-owned lands, and private lands, encompassing about 1,700,000 acres (6,900 km2).[91]

In 1989, the second island propagation project was initiated with release of a population on Horn Island off the Mississippi coast. This population was removed in 1998 because of a likelihood of encounters with humans. The third island propagation project introduced a population on St. Vincent Island, Florida, offshore between Cape San Blas and Apalachicola, Florida, in 1990, and in 1997, the fourth island propagation program introduced a population to Cape St. George Island, Florida, south of Apalachicola.

In 1991, two pairs were reintroduced into the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where the last known red wolf was killed in 1905. Despite some early success, the wolves were relocated to North Carolina in 1998, ending the effort to reintroduce the species to the park.

In 1996, the red wolf is listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as a critically endangered species.[2]

In 2007, the USFWS estimated that 300 red wolves remained in the world, with 207 of those in captivity.[92]

By 1999, introgression of coyote genes was recognized as the single greatest threat to wild red wolf recovery and an adaptive management plan which included coyote sterilization has been successful, with coyote genes being reduced by 2015 to < 4% of the wild red wolf population.[16]

Interbreeding with the coyote has been recognized as a threat affecting the restoration of red wolves. Currently, adaptive management efforts are making progress in reducing the threat of coyotes to the red wolf population in northeastern North Carolina. Other threats, such as habitat fragmentation, disease, and anthropogenic mortality, are of concern in the restoration of red wolves. Efforts to reduce the threats are presently being explored.[80]

Over 30 facilities participate in the red wolf Species Survival Plan and oversee the breeding and reintroduction of over 150 wolves.[93]

In 2012, the Southern Environmental Law Center filed a lawsuit against the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission for jeopardizing the existence of the wild red wolf population by allowing nighttime hunting of coyotes in the five-county restoration area in eastern North Carolina.[94] A 2014 court-approved settlement agreement was reached that banned nighttime hunting of coyotes and requires permitting and reporting coyote hunting.[94] In response to the settlement, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission adopted a resolution requesting the USFWS to remove all wild red wolves from private lands, terminate recovery efforts, and declare red wolves extinct in the wild.[95] This resolution came in the wake of a 2014 programmatic review of the red wolf conservation program conducted by The Wildlife Management Institute.[96][97][98] The Wildlife Management Institute indicated the reintroduction of the red wolf was an incredible achievement. The report indicated that red wolves could be released and survive in the wild, but that illegal killing of red wolves threatens the long-term persistence of the population.[98] The report stated that the USFWS needed to update its red wolf recovery plan, thoroughly evaluate its strategy for preventing coyote hybridization and increase its public outreach.[99] Since the programmatic review, the USFWS ceased implementing the red wolf adaptive management plan that was responsible for preventing red wolf hybridization with coyotes and allowed the release of captive-born red wolves into the wild population.[100] Since then, the wild population has decreased from 100–115 red wolves to 50–65.[101] Despite the controversy over the red wolf's status as a unique taxon as well as the USFWS' apparent disinterest towards wolf conservation in the wild, the vast majority of public comments (including NC residents) submitted to the USFWS in 2017 over their new wolf management plan were in favor of the original wild conservation plan.[102]

In 2014, the USFWS issued the first take permit for a red wolf to a private landowner.[103] Since then, the USFWS issued several other take permits to landowners in the five-county restoration area. During June 2015, a landowner shot and killed a female red wolf after being authorized a take permit, causing a public outcry.[104][105] In response, the Southern Environmental Law Center filed a lawsuit against the USFWS for violating the Endangered Species Act.[106]

A 2016 genetic study of canid scats found that despite high coyote density inside the Red Wolf Experimental Population Area (RWEPA), hybridization occurs rarely (4% are hybrids). High wolf mortality related to anthropogenic causes appeared to be the main factor limiting wolf dispersal westward from the RWEPA.[107] High anthropogenic wolf mortality similarly limits expansion of eastern wolves outside of protected areas in south-eastern Canada.[108]

By 2016, the red wolf population of North Carolina had declined to 45-60 wolves. The largest cause of this decline was gunshot.[109]

In June 2018, the USFWS announced a proposal that would limit the wolves' safe range to only Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge where only about 35 wolves remain, thus allowing hunting on private land.[110][111]

Gallery

Showing color variation

Showing color variation In winter

In winter Red wolf in a breeding program. Less than 100 remain in the wild.

Red wolf in a breeding program. Less than 100 remain in the wild. With radio collar

With radio collar

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nowak, Ronald M. (2002). "The Original Status of Wolves in Eastern North America". Southeastern Naturalist. 1 (2): 95–130. doi:10.1656/1528-7092(2002)001[0095:TOSOWI]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 Kelly BT, Beyer A & Phillips MK (2008). "Canis rufus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2008: e.T3747A10057394. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3747A10057394.en. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 Audubon, J. and Bachman J. (1851) The Vivaparous Quadrupeds of North America, Volume 2. New York, NY. p.240.

- 1 2 3 4 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA576

- 1 2 Mech, L.1970. The wolf: The ecology and behavior of an endangered species. Natural History Press, Garden City, NY. pp. 22-25, 285, 331.

- 1 2 Roskov Y., Abucay L., Orrell T., Nicolson D., Bailly N., Kirk P.M., Bourgoin T., DeWalt R.E., Decock W., De Wever A., Nieukerken E. van, Zarucchi J., Penev, L, eds. (May 2018). "Canis lupus rufus Audubon and Bachman, 1851". Catalogue of Life 2018 Checklist. Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Goldman E (1937). "The wolves of North America". Journal of Mammalogy. 18: 37–45. doi:10.2307/1374306. JSTOR 1374306.

- ↑ Glover, A. (1942), Extinct and vanishing mammals of the western hemisphere, with the marine species of all the oceans, American Committee for International Wild Life Protection, pp. 229-233.

- ↑ Reich, D.E.; Wayne, R.K.; Goldstein, D.B. (1999). "Genetic evidence for a recent origin by hybridization of red wolves". Molecular Ecology. 8 (1): 139–144. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00514.x. PMID 9919703.

- 1 2 Joseph W. Hinton; Michael J. Chamberlain; David R. Rabon Jr. (August 2013). "Red Wolf (Canis rufus) Recovery: A Review with Suggestions for Future Research". Animals. 3 (3): 722–724. doi:10.3390/ani3030722. PMC 4494459. PMID 26479530. Retrieved 2015-08-16.

- 1 2 3 Paradiso, J. L.; Nowak, R. M. (1972). "Canis rufus" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 22 (22): 1–4. doi:10.2307/3503948. JSTOR 3503948. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-16.

- 1 2 3 Woodward, D. W. (1980), The Red Wolf, FWS

- ↑ "Red wolf (Canis rufus)". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: Environmental Conservation Online System.

- ↑ "The 5 Most Endangered Canine Species", Sciam.com, John R. Platt, May 9, 2013, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/extinction-countdown/ost-endangered-canine-species/

- ↑ Hendry, D. (2007). "Red Wolf Restoration: A 20-Year Journey". International Wolf Center. 17: 4.

- 1 2 Eric M. Gese; Fred F. Knowlton; Jennifer R. Adams; Karen Beck; Todd K. Fuller; Dennis L. Murray; Todd D. Steury; Michael K. Stoskopf; Will T. Waddell; Lisette P. Waits (2015). "Managing hybridization of a recovering endangered species: The red wolf Canis rufus as a case study" (PDF). Current Zoology. 61 (1): 191–205. doi:10.1093/czoolo/61.1.191. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ "Government: Wild red wolf population could soon be wiped out". www.msn.com. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- 1 2 L. Y. Rutledge; S. Devillard; J. Q. Boone; P. A. Hohenlohe; B. N. White (July 2015). "RAD sequencing and genomic simulations resolve hybrid origins within North American Canis". Biology Letters. 11: 1–4. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0303. PMC 4528444. PMID 26156129. Retrieved 2015-08-16.

- 1 2 R.M. Nowak (2003). "Chapter 9 - Wolf evolution and taxonomy". In Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi. Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. pp. 239–258. ISBN 978-0-226-51696-7.

- 1 2 Paul A. Hohenlohe, Linda Y. Rutledge, Lisette P. Waits, Kimberly R. Andrews, Jennifer R. Adams, Joseph W. Hinton, Ronald M. Nowak, Brent R. Patterson, Adrian P. Wydeven, Paul A. Wilson, Brad N. White (2017). "Comment on "Whole-genome sequence analysis shows two endemic species of North American wolf are admixtures of the coyote and gray wolf"". Science Advances. 3 (6): e1602250. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E2250H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1602250. PMC 5462499. PMID 28630899.

- 1 2 Schmitt, E; Wallace, S (2014). "Shape Change and Variation in the Cranial Morphology of Wild Canids (Canis lupus, Canis latrans, Canis rufus) Compared to Domestic Dogs (Canis familiaris) Using Geometric Morphometrics". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 24: 42. doi:10.1002/oa.1306.

- ↑ Fredrickson RJ, Hedrick PW. 2006. Dynamics of Hybridization and Introgression in Red Wolves and Coyotes. Conservation Biology 20(4):1272–1283

- 1 2 3 4 Nowak, Ronald M. (1979). "North American Quaternary Canis". 6. Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas: 39. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.4072. ISBN 978-0-89338-007-6. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ "Red Wolf Recovery Program". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Program. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- 1 2 3 Beeland, T. (2013). "8-Tracing the Origins of Red Wolves". The Secret World of Red Wolves: The Fight to Save North America's Other Wolf. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 105–123. ISBN 978-1-4696-0199-1.

- ↑ Catesby, M (1771) "The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands". Royal Society London, 2 vols. p.xxvi

- ↑ Bartram, W. (1791) "Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws. Containing an Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions; Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians", James & Johnson Philadelphia, p197. The second edition that was printed in London in 1794 can be found here

- 1 2 3 Phillips, M.; Henry, V.; Kelly, B. (2003). "ch.11-Restoration of the Red Wolf". In Mech, L. D.; Boitani, L. Wolves, Behavior, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. pp. 272–274. ISBN 0226516970.

- ↑ Bailey, V. (1905) "Biological survey of Texas : Life zones, with characteristic species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and plants. Reptiles, with notes of distribution. Mammals, with notes on distribution, habits and economic importance", North American fauna; no. 25. p.174

- 1 2 Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America. 2. Dover Publications, New York. pp. 413–477. ISBN 0486211932.

- 1 2 McCarley, H. (1962) The Taxonomic Status of Wild Canis (Canidae) in the South Central United States, The Southwestern Naturalist, Vol. 7, No. 3/4 (Dec. 15, 1962), pp. 227-235

- ↑ Paradiso, J. (1968). "Canids recently collected in east Texas, with comments on the taxonomy of the red wolf". Am. Midl. Nat. 80 (2): 529–34. doi:10.2307/2423543. JSTOR 2423543.

- ↑ Lawrence, B. and Bossert, W. (May, 1967) "Multiple Character Analysis of Canis lupus, latrans, and familiaris, with a Discussion of the Relationships of Canis niger", American Zoologist Vol. 7, No. 2 , pp. 223-232, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Lawrence, B. and W. Bossert. 1975. Relationships of North American Canis shown by a multiple character analysis of selected populations. P. 73-86 in M.W. Fox, ed., The wild canids: Their systematic, behavioral ecology, and evolution. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York.

- ↑ Paradiso, J. L., and Nowak, R. M. (1971). A Report on the Taxonomic Status and Distribution of the Red Wolf, U.S. Department of the Interior Special Scientific Report--Wildlife No. 145, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Atkins, D. (1971). "Evolution of the cerebellum in the genus Canis". J. Mammal. 52: 96–97. doi:10.2307/1378435. JSTOR 1378435.

- ↑ Boyko, A. (2009). "Complex population structure in African village dogs and its implications for inferring dog domestication history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (33): 13903–13908. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10613903B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902129106. PMC 2728993. PMID 19666600.

- ↑ Pang, J. (2009). "mtDNA data indicate a single origin for dogs south of Yangtze River, less than 16,300 years ago, from numerous wolves". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (12): 2849–64. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp195. PMC 2775109. PMID 19723671.

- 1 2 Cronin, M. A.; Canovas, A.; Bannasch, D. L.; Oberbauer, A. M.; Medrano, J. F. (2014). "Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Variation of Wolves (Canis lupus) in Southeast Alaska and Comparison with Wolves, Dogs, and Coyotes in North America". Journal of Heredity. 106 (1): 26–36. doi:10.1093/jhered/esu075. PMID 25429025.

- ↑ Bardeleben, Carolyne; Moore, Rachael L.; Wayne, Robert K. (2005). "A molecular phylogeny of the Canidae based on six nuclear loci". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37 (3): 815–31. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.07.019. PMID 16213754.

- ↑ Gray, Melissa M; Sutter, Nathan B; Ostrander, Elaine A; Wayne, Robert K (2010). "The IGF1 small dog haplotype is derived from Middle Eastern grey wolves". BMC Biology. 8: 16. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-16. PMC 2837629. PMID 20181231.

- ↑ Vila, C. (1997). "Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog". Science. 276 (5319): 1687–9. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1687. PMID 9180076.

- ↑ Wayne, Robert K.; Vonholdt, Bridgett M. (2012). "Evolutionary genomics of dog domestication". Mammalian Genome. 23 (1–2): 3–18. doi:10.1007/s00335-011-9386-7. PMID 22270221.

- ↑ Ferrell, Robert E; Morizot, Donald C; Horn, Jacqueline; Carley, Curtis J (1980). "Biochemical markers in a species endangered by introgression: The red wolf". Biochemical Genetics. 18 (1–2): 39–49. doi:10.1007/BF00504358. PMID 6930264.

- ↑ Wayne, R. K; Jenks, S. M (1991). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis implying extensive hybridization of the endangered red wolf Canis rufus". Nature. 351 (6327): 565. Bibcode:1991Natur.351..565W. doi:10.1038/351565a0.

- ↑ Crying Wolf in North America, Gittleman, John L; Pimm, Stuart L; Nature Jun 13, 1991; 351, 6327; ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Source pg. 524

- ↑ Nowak, Ronald M (1992). "The Red Wolf is Not a Hybrid". Conservation Biology. 6 (4): 593. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.06040593.x.

- ↑ Dowling, Thomas E; Minckley, W.L; Douglas, Michael E; Marsh, Paul C; Demarais, Bruce D (1992). "Response to Wayne, Nowak, and Phillips and Henry: Use of Molecular Characters in Conservation Biology". Conservation Biology. 6 (4): 600. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.06040600.x.

- ↑ Roy, M.S., Geffen, E., Smith, D., Ostrander, E.A., and Wayne, R.K. 1994. Pattern of differentiation and hybridization in North American wolflike canids, revealed by analysis of microsatellite loci. Mol. Biol. Evol. 11: 553–570.

- ↑ Brewster, W.G., and Fritts, S.H. 1995. Taxonomy and genetics of the gray wolves in western North America. In Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World: Proceedings of the Second North American Symposium on wolves. Edited by L.N. Carbyn, S.H. Fritts, and D.R. Seip. Canadian Circumpolar Institute, University of Alberta, Edmonton. pp. 353–373.

- ↑ Nowak et al. (1995). Another look at wolf taxonomy. pp 375–397 In L.N. Carbyn, S.H. Fritts, and D.R. Seip, eds. Ecology and conservation of wolves in a changing world. Canadian Circumpolar Institute, Edmonton, Alberta.

- ↑ Nowak, R.M., Phillips, M.K., Henry, V.G., Hunter, W.C., and Smith, R. 1995. The origin and fate of the red wolf. In Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World: Proceedings of the Second North American Symposium on Wolves. Edited by L.N. Carbyn, S.H. Fritts, and D.R. Seip. Canadian Circumpolar Institute, University of Alberta, Edmonton. pp. 409–415.

- 1 2 Roy, M.S., Geffen, E., Smith, D., and Wayne, R.K. 1996. Molecular genetics of pre-1940 red wolves. Conserv. Biol. 10: 1413–1424.

- ↑ Nowak, R.M., and Federoff, N.E. 1998. Validity of the red wolf:response to Roy et al. Conserv. Biol. 12: 722–725.

- ↑ Wayne, R.K., Roy, M.S., and Gittleman, J.L. 1998. Origin of the red wolf: response to Nowak and Federoff and Gardener. Conserv. Biol. 12: 726–729.

- ↑ Reich, D. E; Wayne, R. K; Goldstein, D. B (1999). "Genetic evidence for a recent origin by hybridization of red wolves". Molecular Ecology. 8 (1): 139–44. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.1999.00514.x. PMID 9919703.

- ↑ Wilson, Paul J; Grewal, Sonya; Lawford, Ian D; Heal, Jennifer NM; Granacki, Angela G; Pennock, David; Theberge, John B; Theberge, Mary T; Voigt, Dennis R; Waddell, Will; Chambers, Robert E; Paquet, Paul C; Goulet, Gloria; Cluff, Dean; White, Bradley N (2000). "DNA profiles of the eastern Canadian wolf and the red wolf provide evidence for a common evolutionary history independent of the gray wolf". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 78 (12): 2156. doi:10.1139/z00-158.

- ↑ Koblmüller, Stephan; Nord, Maria; Wayne, Robert K; Leonard, Jennifer A (2009). "Origin and status of the Great Lakes wolf". Molecular Ecology. 18 (11): 2313. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04176.x. PMID 19366404.

- ↑ Vonholdt, Bridgett M; Pollinger, John P; Earl, Dent A; Knowles, James C; Boyko, Adam R; Parker, Heidi; Geffen, Eli; Pilot, Malgorzata; Jedrzejewski, Wlodzimierz; Jedrzejewska, Bogumila; Sidorovich, Vadim; Greco, Claudia; Randi, Ettore; Musiani, Marco; Kays, Roland; Bustamante, Carlos D; Ostrander, Elaine A; Novembre, John; Wayne, Robert K (2011). "A genome-wide perspective on the evolutionary history of enigmatic wolf-like canids". Genome Research. 21 (8): 1294. doi:10.1101/gr.116301.110. PMID 21566151.

- ↑ Chambers, Steven M.; Fain, Steven R.; Fazio, Bud; Amaral, Michael (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna. 77: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ↑ Dumbacher, J., Review of Proposed Rule Regarding Status of the Wolf Under the Endangered Species Act, NCEAS (January 2014)

- 1 2 Brzeski, Kristin E.; Debiasse, Melissa B.; Rabon, David R.; Chamberlain, Michael J.; Taylor, Sabrina S. (2016). "Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Southeastern Pre-Columbian Canids" (PDF). Journal of Heredity. 107 (3): 287–293. doi:10.1093/jhered/esw002. PMC 4885236. PMID 26774058.

- 1 2 3 Vonholdt, B. M.; Cahill, J. A.; Fan, Z.; Gronau, I.; Robinson, J.; Pollinger, J. P.; Shapiro, B.; Wall, J.; Wayne, R. K. (2016). "Whole-genome sequence analysis shows that two endemic species of North American wolf are admixtures of the coyote and gray wolf". Science Advances. 2 (7): e1501714. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1714V. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501714.

- ↑ Morell, Virginia (2016). "How do you save a wolf that's not really a wolf?". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aag0699.

- ↑ Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H. (2008). Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13528-3. OCLC 185095648.

- ↑ Science leads Fish and Wildlife Service to significant changes for red wolf recovery, Red Wolf Program Review, US Fish and Wildlife Service, 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Science leads Fish and Wildlife Service to significant changes for red wolf recovery by Jeff Fleming. Media Release, US Fish and Wildlife Service, 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Vonholdt, Bridgett M.; Cahill, James A.; Gronau, Ilan; Shapiro, Beth; Wall, Jeff; Wayne, Robert K. (2017). "Response to Hohenloheet al". Science Advances. 3 (6): e1701233. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E1233V. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1701233. PMC 5462503. PMID 28630935.

- 1 2 Hinton, Joseph W.; Chamberlain, Michael J. (2014-08-22). "Morphometrics of Canis taxa in eastern North Carolina". Journal of Mammalogy. 95 (4): 855–861. doi:10.1644/13-MAMM-A-202. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1859), "On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life", Nature (Full image view 1st ed.), London: John Murray, 5 (121): 92, Bibcode:1872Natur...5..318B, doi:10.1038/005318a0, retrieved 2011-03-01

- 1 2 Hinton, Joseph W.; Chamberlain, Michael J. (2010-01-01). "Space and Habitat Use by a Red Wolf Pack and Their Pups During Pup-Rearing". Journal of Wildlife Management. 74 (1): 55–58. doi:10.2193/2008-583. ISSN 1937-2817.

- ↑ Sparkman, Amanda M.; Adams, Jennifer; Beyer, Arthur; Steury, Todd D.; Waits, Lisette; Murray, Dennis L. (2011-05-07). "Helper effects on pup lifetime fitness in the cooperatively breeding red wolf (Canis rufus)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1710): 1381–1389. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1921. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3061142. PMID 20961897.

- 1 2 Sparkman, AM; Adams, JR; Steury, TD; Waits, LP; Murray, DL (July 2012). "Pack social dynamics and inbreeding avoidance in the cooperatively breeding red wolf". Behavioral Ecology. 23 (6): 1186–1194. doi:10.1093/beheco/ars099.

- ↑ Charlesworth D, Willis JH (2009). "The genetics of inbreeding depression". Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 (11): 783–96. doi:10.1038/nrg2664. PMID 19834483.

- ↑ Shaw, J.1975. Ecology, behavior and systematic of the red wolf (Canis rufus). Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

- ↑ Dellinger, Justin A.; Ortman, Brian L.; Steury, Todd D.; Bohling, Justin; Waits, Lisette P. (2011-12-01). "Food Habits of Red Wolves during Pup-Rearing Season". Southeastern Naturalist. 10 (4): 731–740. doi:10.1656/058.010.0412. ISSN 1528-7092.

- ↑ McVey, Justin M.; Cobb, David T.; Powell, Roger A.; Stoskopf, Michael K.; Bohling, Justin H.; Waits, Lisette P.; Moorman, Christopher E. (2013-10-15). "Diets of sympatric red wolves and coyotes in northeastern North Carolina". Journal of Mammalogy. 94 (5): 1141–1148. doi:10.1644/13-MAMM-A-109.1. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ↑ Powell, W. S. (1973). Creatures of North Carolina from Roanoke Island to Purgatory Mountain. North Carolina Historical Review, 50 (2 ), 121-168.

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.1997. Endangered Red Wolves. http://library.fws.gov/Pubs4/endangered_red_wolves.pdf:p7.

- 1 2 3 "Current Red Wolf Facts," found on the Red Wolf Recovery web page, http://www.fws.gov/redwolf/index.html, accessed on July 5, 2011.

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.1997. Endangered Red Wolves. http://library.fws.gov/Pubs4/endangered_red_wolves.pdf:1-pp.8-9.

- ↑ National Park Service. "Mammals". Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ Camuto, C. (2000), Another Country: Journeying Toward the Cherokee Mountains, University of Georgia Press, ISBN 0-8203-2237-7

- ↑ Lopez, B. H. (1978), Of Wolves and Men, J. M. Dent and Sons Limited, p. 109, ISBN 0-7432-4936-4

- ↑ Young, S. P. (1940) Review of "North American Big Game", Journal of Mammology vol. 21, pp 96-98

- ↑ Carley, C (1975). Activities and findings of the red wolf recovery program from late 1973 to July 1, 1975 (Report). Albuquerque, NM: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ↑ McCarley, H. & J. Carley (1979). Recent changes in distribution and status of red wolves (Canis rufus) Endangered Species Report no.4 (Report). Albuquerque, NM: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ↑ Red Wolf Recovery/Species Survival Plan (Report). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1990.

- 1 2 Carley, Curtis J. 1979. "Report on the Successful Translocation Experiment of Red Wolves (Canis rufus) to Bulls Island, S.C." Presentation at the Portland Wolf Symposium, Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon, August 13–17, 1979.

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Cape Romain NWR, red wolf web page

- ↑ USFWS.2010. Red Wolf Recovery Program, 1st Quarter Report, October–December 2010, Manteco, NC.

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Red Wolf (Canis rufus) 5-Year Status Review: Summary and Evaluation.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- 1 2 "Protection of Red Wolves | Animal Welfare Institute". awionline.org. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission > News > News Article". www.ncwildlife.org. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "WMI to Coordinate Comprehensive Review and Evaluation of the Red Wolf Recovery Program". www.wildlifemanagementinstitute.org. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ Resolution Requesting that the United States Fish and Wildlife Service Declare the Red Wolf (Canis rufus) Extinct in the Wild and Terminate the Red Wolf Reintroduction Program in Beaufort, Dare, Hyde, Tyrrell, and Washington Counties, North Carolina (January 29, 2015)

- 1 2 "Red Wolf Recovery Program". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "Wildlife Management Institute Releases New Report on Red Wolf Recovery Program". Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "Service Halts Red Wolf Reintroductions Pending Examination of Recovery Program". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "2015 Brings No Conclusions On Red Wolf Recovery Program In Eastern NC". wfae.org. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "Public Overwhelmingly Supports Protecting Wild Red Wolves". www.biologicaldiversity.org. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ↑ "USFWS Grants Landowner Permit to Kill Critically Endangered Red Wolf | Wolf Conservation Center". nywolf.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "How management rule allows certain red wolf killings". newsobserver. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "Sierra Weaver: No defense for death of red wolf". newsobserver. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ "U.S. Fish and Wildlife faces lawsuit over red wolf program". newsobserver. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- ↑ Justin H. Bohling; Justin Dellinger; Justin M. McVey; David T. Cobb; Christopher E. Moorman & Lisette P. Waits (July 2016). "Describing a developing hybrid zone between red wolves and coyotes in eastern North Carolina, USA". Evolutionary Applications. 9 (6): 791–804. doi:10.1111/eva.12388. PMC 4908465. PMID 27330555. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ↑ Benson, J.; B. Patterson & P. Mahoney (2014). "A protected area influences genotype specific survival and the structure of a Canis hybrid zone". Ecology. 95 (2): 254–264. doi:10.1890/13-0698.1. PMID 24669720. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ↑ Hinton, Joseph W.; White, Gary C.; Rabon, David R.; Chamberlain, Michael J. (2017). "Survival and population size estimates of the red wolf". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 81 (3): 417. doi:10.1002/jwmg.21206.

- ↑ bopete@postandcourier.com, Bo Petersen. "Fish and Wildlife to allow open hunting of endangered wild red wolves in Southeast". Post and Courier. Retrieved 2018-06-29.

- ↑ "Service proposes new management rule for non-essential, experimental population of red wolves in North Carolina | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2018-06-29.

Further reading

- FWS – Red Wolf 5-year review 2018

- ^ R. Nowak, R.M. (1992). "The red wolf is not a hybrid.". Conservation Biology 6 : 593-595.

- Hinton, J. W.; Chamberlain, M. J.; Rabon, D. R. (2013). "Red Wolf (Canis rufus) Recovery: A Review with Suggestions for Future Research". Animals. 3 (3): 722–744. doi:10.3390/ani3030722. PMC 4494459. PMID 26479530.

- ^ Roy, M.S., Geffen, E., Smith, D., Ostrander, E.A. & Wayne, R.K. (1994). "Patterns of differentiation and hybridization in North American wolflike canids, revealed by analysis of micro satellite loci.". Molecular Biology and Evolution 11 : 553–570.

- ^ Roy, M.S., Girman, D.G., Taylor, A.C. & Wayne, R.K. (1994). "The use of museum specimens to reconstruct the genetic variability and relationships of extinct populations.". Experientia 50 : 551-557.

- ^ Silverstein, A., Silverstein, V. B. & Silverstein, R. A. (1994). "The Red wolf: endangered in America.". Brookfield: Conn. Millbrook Press.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Canis rufus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- ARKive – images and movies of the Red wolf (Canis rufus)

- Red Wolf Species Overview at Enature.com using Wayback Machine

- Red Wolf, International Wolf Center

- The Red Wolf Coalition

- Wolf Source