African wildcat

| African wildcat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Felis |

| Species: | F. lybica |

| Binomial name | |

| Felis lybica Forster, 1780 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Felis silvestris lybica Forster, 1780 | |

The African wildcat (Felis lybica[1]), also called Near Eastern wildcat is a wildcat species that lives in Northern Africa, the Near East and around the periphery of the Arabian Peninsula.[2][3] The status Least Concern on the IUCN Red List is attributed to the species, including all subspecies of wildcats.[4]

The African wildcat appears to have diverged from the other species about 131,000 years ago. Some individual African wildcats were first domesticated about 10,000 years ago in the Near East, and are the ancestors of the domestic cat.[3] The tomb of an African wildcat was found alongside a human tomb in Shillourokambos, a Pre-Pottery Neolithic B site in Cyprus that are estimated to have been established by Neolithic farmers about 9,500 years ago.[5] Crossings between domestic cats and African wildcats are still common today.[6]

Taxonomy

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Felis lineage[7] |

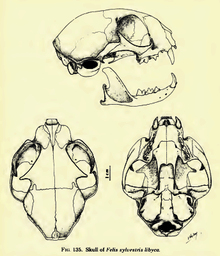

Characteristics

The fur colour of the African wildcat is light sandy grey, and sometimes with a pale yellow or reddish hue. The ears are reddish to grey, with long light yellow hairs around the pinna. The stripes around the face are dark ochre to black: two run horizontally on the cheek, and four to six across the throat. A dark stripe runs along the back, the flanks are lighter, and the belly is whitish. Pale vertical stripes on the sides often dissolve into spots. Two dark rings are on the forelegs, and hind legs are striped. The feet are dark brown to black.[8]

Pocock described the African wildcat as differing from the European wildcat by inconspicuous stripes on the nape and shoulders, a less sharply defined stripe on the spinal area and by the slender tail, which is cylindrical, less bushy and more tapering. Ears are normally tipped with a small tuft.[9]

Skins of male wildcats from Northern Africa measured 47–59.7 cm (18.5–23.5 in) in head-to-body length with a 26.7–36.8 cm (10.5–14.5 in) long tail. Skins of female wildcats measured 40.6–55.8 cm (16.0–22.0 in) with a 24.1–33.7 cm (9.5–13.3 in) long tail.[10] Male wildcats from Yemen measured 46–57 cm (18–22 in) in head-to-body length with a 25–32 cm (9.8–12.6 in) long tail; females were slightly smaller measuring 50–51 cm (20–20 in) in head-to-body length with a 25–28 cm (9.8–11.0 in) long tail. Both females and males ranged in weight from 3.2 to 4.5 kg (7.1 to 9.9 lb).[11]

Its fur is shorter than that of the European wildcat, and it is considerably smaller.

Distribution and habitat

The African wildcat occurs across northern Africa, in the Near East, around the periphery of the Arabian Peninsula to the Caspian Sea.[3] In Africa, it ranges from Morocco into Egypt, and inhabits the savannas of West Africa from Mauritania to the Horn of Africa, including Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Sudan, southwards to South Africa. It inhabits a broad variety of habitats, especially in hilly and mountainous landscapes such as the Hoggar Mountains. But in deserts such as the Sahara, it occurs at much lower densities.[4] The sand cat is much better adapted to desert environments.[2]

The wild cats in Sardinia were long considered a subspecies of the African wildcat.[9] But results of zooarchaeological research indicate that they descended from domestic cats introduced about 2000 years ago from the Near East or Sub-Saharan Africa.[12] The population on Corsica also descended from introduced domestic cats and is considered a feral cat.[13]

The wild cats on the island of Sicily are considered European wildcats.[12][14]

Ecology and behaviour

African wildcats are active mainly by night and search for prey. Their hearing is so fine that they can locate prey precisely. They approach prey by patiently crawling forward and using vegetation to hide. They rarely drink water.[15] They hunt primarily mice, rats, birds, reptiles, and insects.[16][17]

When confronted, the African wildcat raises its hair to make itself seem larger in order to intimidate its opponent. In the daytime it usually hides in the bushes, although it is sometimes active on dark cloudy days. The territory of a male overlaps with that of up to three females.[18]

Reproduction

Females give birth to one to three kittens, mostly during the warm wet season.[16]

The African wildcat often rests and gives birth in burrows or hollows in the ground. The gestation period lasts between 56 and 69 days. The kittens are born blind and need the full care of the mother. They stay with their mother for five to six months and are fertile after six months.

Evolution

Based on a mitochondrial DNA study of 979 domestic and wildcats from Europe, Asia, and Africa, the African wildcat is thought to have split off from the European wildcat about 173,000 years ago, with the North African/Near Eastern subspecies (F. l. lybica) splitting from the Asiatic wildcat (F. l. ornata) and the Southern African wildcat (F. l. cafra) about 131,000 years ago. About 10,000 years ago, some individual African wildcats were tamed in the Middle East and are the ancestors of the domestic cat. Modern domestic cats are derived from at least five "Mitochondrial Eves". The African wildcat easily interbreeds with feral domestic cats.[3]

Domestication occurred in the Middle East possibly at more than one location in Egypt and Turkey. African wildcats were traded throughout the region resulting in genetic mixing. Egyptian art depicts the changing role of the cat from field hunter in 1950 BCE to human companion by 1500 BCE. These tamed Egyptian cats are thought to be the ancestors of domestic cats.[19][20]

Conservation

The African wildcat is included in CITES Appendix II.[4]

Alley Cat Rescue is currently the only organization known to have a program specifically aimed at conserving African wildcats and reducing what some refer to as genetic pollution by domestic cats.

It has been discovered that a domestic cat can serve as a surrogate mother for wildcat embryos. The numerous similarities between the two species mean that an embyro of an African wildcat may be carried and borne by a domestic cat. A documentary by the BBC describes the details of the experiments that led to this discovery, and also shows a mature wildcat that was born by a surrogate female.[21]

In philately

The Libyan Posts, in cooperation with World Wide Fund for Nature, dedicated a postage stamp issue to Felis lybica on November 1, 1997. The issue was also released as a set of four stamps printed on a minisheet.[22]

References

- ↑ Kitchener, A. C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Eizirik, E., Gentry, A., Werdelin, L., Wilting A., Yamaguchi, N., Abramov, A. V., Christiansen, P., Driscoll, C., Duckworth, J. W., Johnson, W., Luo, S.-J., Meijaard, E., O’Donoghue, P., Sanderson, J., Seymour, K., Bruford, M., Groves, C., Hoffmann, M., Nowell, K., Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11.

- 1 2 Nowell, K., Jackson, P. (1996). African Wildcat Felis silvestris, lybica group (Forster, 1770) Archived 2012-11-29 at the Wayback Machine. In: Wild Cats: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland.

- 1 2 3 4 Driscoll, C. A.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Roca, A. L.; Hupe, K.; Johnson, W. E.; Geffen, E.; Harley, E. H.; Delibes, M.; Pontier, D.; Kitchener, A. C.; Yamaguchi, N.; O'Brien, S. J.; Macdonald, D. W. (2007), "The near eastern origin of cat domestication", Science, 317: 519–523, doi:10.1126/science.1139518, PMC 5612713, PMID 17600185 .

- 1 2 3 Yamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A.; Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. (2015). "Felis silvestris". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2015: e.T60354712A50652361. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ↑ Vigne, J. D.; Guilaine, J.; Debue, K.; Haye, L.; Gérard, P. (2004). "Early taming of the cat in Cyprus". Science. 304 (5668): 259–259. doi:10.1126/science.1095335.

- ↑ Kingdon, J. (1988). "Wild Cat (Felis sylvestris)". East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part A: Carnivores. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-43721-3.

- ↑ Mattern, M.Y.; McLennan, D.A. (2000). "Phylogeny and speciation of felids". Cladistics. 16 (2): 232–53. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2000.tb00354.x.

- ↑ Hufnagl, E., Craig-Bennett, A., and Van Weerd, E. (1972). African Wild Cat. In: Libyan Mammals. Oleander Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Page 42.

- 1 2 Pocock, R. I. (1951). Catalogue of the Genus Felis. Trustees of the British Museum, London.

- ↑ Pocock, R. I. (1944). The Races of the North African Wild Cat (Felis lybica). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 114 (1–2): 65–73.

- ↑ Al-Safadi, M. M.; Nader, I. A. (1990). "First record of the wild cat, Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777 from the Yemen Arab Republic (Carnivora: Felidae)". Mammalia. 54 (4): 621–626. doi:10.1515/mamm.1990.54.4.621.

- 1 2 3 Gippoliti, Spartaco; Amori, Giovanni (January 2006). "Ancient introductions of mammals in the Mediterranean Basin and their implications for conservation". Mammal Review. 36 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00081.x.

- ↑ Vigne, Jean-Dénis (June 1992). "Zooarchaeology and the biogeographical history of the mammals of Corsica and Sardinia since the last ice age". Mammal Review. 22 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1992.tb00124.x.

- ↑ Mattucci, F.; Oliveira, R.; Bizzarri, L.; Vercillo, F.; Anile, S.; Ragni, B.; Lapini, L.; Sforzi, A.; Alves, P. C.; Lyons, L. A.; Randi, E. (August 2013). "Genetic structure of wildcat (Felis silvestris) populations in Italy". Ecology and Evolution. 3 (8): 2443–2458. doi:10.1002/ece3.569.

- ↑ Dragesco-Joffe, A. (1993). The African Wildcat, ancestor of the domestic cat. In La vie sauvage du Sahara: 134-136. Lausanne: Delachaux et Niestle.

- 1 2 Smithers, R. H. N. (1971). The Mammals of Botswana. University of Pretoria, South Africa.

- ↑ Hufnagel E. (1972). African Wild Cat Felis lybica. In: Libyan mammals. The Oleander Press. Page 42.

- ↑ Estes, R. D. (1999). The Safari Companion. Russel Friedman Books. ISBN 1-890132-44-6.

- ↑ Ottoni, C; Van Neer, W.; De Cupere, B.; Daligault, J. et al. (2017). "The palaeogenetics of cat dispersal in the ancient world". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1: 0139. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0139.

- ↑ Grimm, D. (2017). "Ancient Egyptians may have given cats the personality to conquer the world". Science | AAAS. 356 (6343). Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ Wild cat mothered by a domestic cat! - Making Animal Babies - BBC Earth

- ↑ "Libyan Stamps online". Archived from the original on 2012-07-26. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Felis silvestris lybica. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Felis silvestris lybica |