European wildcat

| European Wildcat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Felis |

| Species: | F. silvestris |

| Subspecies: | F. s. silvestris |

| Trinomial name | |

| Felis silvestris silvestris | |

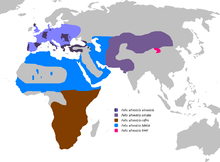

| Approximate European wildcat range within Europe, excluding the Asian part of Turkey and the Caucasus | |

The European wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) is the nominate subspecies of the wildcat that inhabits forests of Western, Southern, Central and Eastern Europe up to the Caucasus Mountains. It is absent in Scandinavia and has been extirpated in England and Wales.[2]

In France and Italy, the European wildcat is predominantly nocturnal, but also active in the daytime when undisturbed by human activities.[3][4]

Characteristics

The European wildcat is on average bigger and stouter than the domestic cat, has longer fur and a shorter non-tapering bushy tail. It has striped fur and a dark dorsal band.[5] Males average a weight of 5 kg (11 lb) up to 8 kg (18 lb), and females 3.5 kg (7.7 lb). Their weight fluctuates seasonally up to 2.5 kg (5.5 lb).[6]

Large males in Spain reach 65 cm (26 in) in length, with a 34.5 cm (13.6 in) long tail, and weigh up to 7.5 kg (17 lb). They also have a less diffuse stripe pattern, proportionally larger teeth, and feed more often on rabbits than the wildcats north of the Douro-Ebro, which are more dependent on small rodents.[7]

Since European wildcats and domestic cats interbreed, it is difficult to distinguish European wildcats and striped hybrids correctly on the basis of only morphological characteristics.[8]

Distribution and habitat

European wildcats live primarily in broad-leaved and mixed forests. They avoid intensively cultivated areas and settlements.[9] The northernmost population lives in northern and eastern Scotland.[10] There are two disconnected populations in France. The one in the Ardennes in the country's north-east extends to Luxembourg, Germany and Belgium. The other in southern France may be connected via the Pyrenees to populations in Spain and Portugal.[11] In Germany, the Rhine is a major barrier between the population in Eifel and Hunsrück mountains west of the river and populations east of the river, where a six-lane highway hampers dispersal.[12] The population in the Polish Carpathian Mountains extends to northern Slovakia and western Ukraine.[13][14] In Switzerland, wildcats are present in the Jura Mountains.[15] Three fragmented populations in Italy comprise one in the country's central and southern part, one in the eastern Alps that may be connected to populations in Slovenia and Croatia. The Sicilian population is the only Mediterranean insular population that has not been introduced.[16]

Evolution

In European Pleistocene deposits, remains of small cats are not uncommon, and indicate a close relationship to the European wildcat.[17]

Threats

In most European countries, European wildcats have become rare. Although legally protected, they are still shot by people mistaking them for feral cats. In the Scottish Highlands, where approximately 400 were thought to remain in the wild in 2004, interbreeding with feral cats is a significant threat to the wild population's distinctiveness.[18] The greatest population of wildcats lives in Spain and Portugal but is threatened by interbreeding with feral cats and loss of habitat.[19][20] In the 1990s, the easternmost population in Ukraine, Moldova, and the Caucasus was threatened by destruction of broad-leaved forests, entailing a reduction of their range. Only small numbers occur in protected areas.[21]

Conservation efforts

In Scotland

In 2012, conservationists reported to have discovered a previously unknown population of Scottish wildcats in the Cairngorms National Park. They are still threatened because of crossbreeding with domestic and feral cats. The scientists reported 465 potential sightings.[23][24][25] In response, the Scottish Wildcat Association disputed the claims, stating in their website, social networks, and press interviews that the sightings were defined as hybrid crossbreeds by leading experts, and that the wildcat population was likely well below 100 individuals.[26]

In September 2012, following a review of 2,000 records including camera trapping photographs, sighting reports, and road kills, the Scottish Wildcat Association (SWA) warned that Scottish wildcats could be extinct within a short time, because only 35 pure wildcats survive in the wild.[27] A severe reduction of rabbit populations due to myxomatosis has hastened the wildcat's decline.[28] In 2013, the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland encouraged collection of biological material, but considered cloning as an option only after "all other avenues have been exhausted".[29]

In September 2013, the Aspinall Foundation announced plans to develop an in-situ captive breeding centre on the island of Càrna, off the west coast of Scotland at Ardnamurchan.[30] The Scottish Wildcat Association had developed the Wildcat Haven project on this peninsula to identify pure Scottish wildcats and neuter feral cats, using a genetic test to identify hybridisation in Scottish wildcats.[31][32]

The news was followed by an SNH announcement to launch a new wildcat Action Plan taking a more "pragmatic" approach to conserve wildcats and hybrids exhibiting wildcat features using a relaxed definition of the wildcat.[33][34] The founder and former chairman of the Scottish Wildcat Association however considered the approach a "shameful effort" that would force the Scottish wildcat into extinction.[33][35][36]

In July 2014, the Wildcat Haven project announced the successful neutering of feral and hybrid cats across 250 sq mi (650 km2) of the West Highlands, creating a protected zone for the Scottish wildcat.[37][38]

On 9 March 2016, an ambitious project was announced to allocate more than 800 square miles of the west Scottish Highlands and to create a further 7,000 square mile haven for wildcats.[39][40] Chief scientist Paul O'Donoghue said: “We have now developed a proven template for wildcat conservation that can be rolled out across the western Highlands. Eight hundred square miles can home around 100 true Scottish wildcats, but our aim is a 7,000 square mile threat-free area that could hold a sustainable population and save them from extinction. Wildcat Haven is living proof that the Scottish wildcat can and must be saved in the wild where they belong. It's all about hybridisation. The wildcat is a very capable survivor and prefers to breed with other wildcats, but it's so outnumbered by domestic cats that hybridisation is inevitable. This means that over a few generations, those wildcat genes are lost, and you're just left with domestic and feral cats causing big problems for prey species and themselves.”[39][40] Scottish Wildcat Action,[41] is another project to save Scottish wildcats involving six priority areas: Strathpeffer, Strathbogie, Strathavon, Morvern, North Strathspey and the Angus Glens.[42]

Taxonomy

Many authorities restrict the subspecies F. s. silvestris to the populations of the European mainland. As per the old classification that considered several different subspecies, the small population of Scottish wildcats is F. s. grampia, the Caucasian wildcat (also including wildcats in Turkey) is F. s. caucasica, the possibly extinct Cretan wildcat is F. s. cretensis, the Balearic wildcat is F. s. jordansi, and the possibly extinct Corsican wildcat is F. s. reyi.[1] But in 2007, a genetic study suggested that the European wildcat populations, including those in Sicily, Anatolia, and the Caucasus Mountains belong to this subspecies as well; on the other hand, populations in Corsica, Sardinia, Crete, and Cyprus turned out to be introduced African wildcats.[22]

Two different forms often are identified in the Iberian Peninsula: the common European form, north of the Douro and Ebro Rivers, and a "giant" Iberian form, sometimes considered a different subspecies F. s. tartessia, in the rest of the region.[43] The palaeontologist Björn Kurtén noted that the disputed "Tartessian" subspecies has uniquely kept the same size and proportions as the form that was found throughout mainland Europe during the Ice Ages of the Pleistocene.[17] The habitat of both forms also is different: the northern, typical population lives mainly in deciduous Quercus robur forests and the southern, large type in Mediterranean evergreen Quercus ilex forests.[7]

In captivity

Despite being closely related to the domestic cat, wildcats have a reputation for being effectively impossible to raise as pets.[44] Naturalist Frances Pitt wrote "there was a time when I did not believe this...my optimism was daunted" by trying to keep a wildcat she named Beelzebina.[45]

References

- 1 2 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 536–537. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A.; Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. (2015). "Felis silvestris". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2015: e.T60354712A50652361. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ↑ Stahl, P. (1986). Le chat forestier d'Europe (Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777): Exploitation des resources et organisation spatiale [The European forest wildcat (Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777): resource exploitation and spatial organization]. Nancy: University of Nancy.

- ↑ Genovesi, P. and Boitani, L. (1993). "Spacing patterns and activity rhythms of a wildcat (Felis silvestris) in Italy". Seminar on the biology and conservation of the wildcat (Felis silvestris), Nancy, France, 23–25 September 1992. Environmental encounters No. 16. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. pp. 98–101.

- ↑ Condé, B., and Schauenberg, P. (1963). Le chat sauvage – dernier félin de France [The wildcat – last feline of France]. Éditions Font-Vive 8: 1–8.

- ↑ Condé, B.; Schauenberg, P. (1971). "Le poids du chat forestier d ́Europe (Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777)" [Weight of the European forest wildcat]. Revue Suisse de Zoologie. 78: 295–315. ISSN 0035-418X.

- 1 2 Garcia-Perea, R. (2006). "Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777". Pp. 333–338 in Atlas y Libro Rojo de los Mamíferos Terrestres de España (Spanish)]. Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, Gobierno de Espagna.

- ↑ Krüger, M.; Hertwig, S. T.; Jetschke, G.; Fischer, M. S. (2009). "Evaluation of anatomical characters and the question of hybridization with domestic cats in the wildcat population of Thuringia, Germany". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 47 (3): 268–282. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2009.00537.x.

- ↑ Nowell, K. and Jackson, P. (1996). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, Gland.

- ↑ Davis, A.R. and Gray, D. (2010). The distribution of Scottish wildcats (Felis silvestris) in Scotland (2006-2008). Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report.

- ↑ Say, L., Devillard, S., Leger, F., Pontier, D. and Ruette, S. (2012). Distribution and spatial genetic structure of European wildcat in France. Animal Conservation 15: 18–27.

- ↑ Hartmann, S. A., Steyer, K., Kraus, R. H. S., Segelbacher, G. and Nowak, C. (2013). Potential barriers to gene flow in the endangered European wildcat (Felis silvestris). Conservation Genetics 14: 413–426.

- ↑ Okarma, H., & Olszańska, A. (2002). The occurrence of wildcat in the Polish Carpathian Mountains. Acta Theriologica 47(4): 499–504.

- ↑ Zagorodniuk, I., Gavrilyuk, M., Drebet, M., Skilsky, I., Andrusenko, A., & Pirkhal, A. (2014). Wildcat (Felis silvestris Schreber, 1777) in Ukraine: modern state of the populations and eastwards expansion of the species. Біологічні студії 8 (3-4): 233–254.

- ↑ Weber, D., Roth, T., Huwyler, S. (2010). Die aktuelle Verbreitung der Wildkatze (Felis silvestris silvestris Schreber, 1777) in der Schweiz. Ergebnisse der systematischen Erhebungen in den Jurakantonen in den Wintern 2008/09 und 2009/10. Hintermann & Weber AG, Bundesamt für Umwelt, Bern.

- ↑ Mattucci F., Oliveira R., Bizzarri L., Vercillo F., Anile S., Ragni B., Lapini L., Sforzi A., Alves P.C., Lyons L.A., Randi E. (2013). "Genetic structure of wildcat (Felis silvestris) populations in Italy". Ecology and Evolution. 3 (8): 2443–2458. doi:10.1002/ece3.569.

- 1 2 Kurtén, B. (1965). "On the evolution of the European Wild Cat, Felis silvestris Schreber". Acta Zoologica Fennica. 111: 3–34.

- ↑ Macdonald, D. W., Daniels, M. J., Driscoll, C. A., Kitchener, A. C. and Yamaguchi, N. (2004). The Scottish Wildcat: analyses for conservation and an action plan. The Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Oxford, UK.

- ↑ Cabral, M. J., Almeida, J., Almeida, P. R., Dellinger, T., Ferrand de Almeida, N., Oliveira, M. E., Palmeirim, J. M., Queiroz, A. I., Rogado, L. and Santos-Reis, M. (eds). (2005). Livro Vermelho dos Vertebrados de Portugal. Instituto da Conservação da Natureza, Lisboa.

- ↑ Palomo, L. J. and Gisbert, J. (2002). Atlas de los mamíferos terrestres de España. Dirección General de Conservación de la Naturaleza. SECEM-SECEMU, Madrid, Spain.

- ↑ Belousova, A.V. (1993). "Small Felidae of Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Far East: survey of the state of populations". Lutreola. 2: 16–21.

- 1 2 Driscoll, C. A.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Roca, A. L.; Hupe, K.; Johnson, W. E.; Geffen, E.; Harley, E. H.; Delibes, M.; Pontier, D.; Kitchener, A. C.; Yamaguchi, N.; O’Brien, S. J.; Macdonald, D. W. (2007). "The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication" (PDF). Science. 317 (5837): 519–523. doi:10.1126/science.1139518. PMC 5612713. PMID 17600185.

- ↑ "Scottish wildcats found in Cairngorms". BBC News. 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ Miller, D. (24 April 2012). "Camera traps capture new Scottish wildcat sites in the Cairngorms". BBC News.

- ↑ Baird, E. (2012). "Practical Wildcat Conservation in the Cairngorms National Park, Conference Report Summary" (PDF). Highland Tiger. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ McQuilan, R. (13 July 2012). "Can Scotland's wildcats be saved from extinction?". Scottish Herald.

- ↑ "Scottish wildcat extinct within months, association says". BBC News. 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ↑ Pooran, N. (2013). "Scottish wildcats hit by rabbit shortage as numbers decline". Deadline News.

- ↑ Gray, S. (1 March 2013). "Wildcat cloning idea rejected by experts – for now". The Courier. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015.

- ↑ "Remote island plan to help save Scottish wildcats from extinction". The Herald. Glasgow. 22 September 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ Wildcat Haven Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. ardtornish.co.uk. January 2013

- ↑ "Scottish wildcat could be extinct 'within two years'". BBC News. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- 1 2 McQuillan, R. (23 September 2013). "Scottish wildcat plan 'will not save animal'". The Herald. Glasgow. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan. snh.org.uk. September 2013

- ↑ McKenna, K. (23 September 2013). "Extinction by stealth: how long can the Scottish wildcat survive?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ "Plan launched to save Scotland's wildcats". Wildlife Extra News. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ Haven to save the wildcat from total extinction. The Herald (Glasgow). 14 July 2014

- ↑ "Scottish wildcat 'safe haven' set up in Ardnamurchan". BBC News. 15 July 2014

- 1 2 The Press and Journal: 800 square miles of Scottish Highlands now dedicated to saving the wildcat

- 1 2 BBC: West Highland wildcat haven extended to cover 800 sq miles

- ↑ Scottish WildCat Action

- ↑ Earth Touch News Network: Scotland's 'Highland Tiger' is a Cat on the Brink - Can We Save It?

- ↑ Purroy, F. J. and Varela, J. M. (2003). Guía de los Mamíferos de España. Península, Baleares y Canarias. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- ↑ Konrad Lorenz (2 September 2003). Man Meets Dog. Routledge. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-134-49899-4.

- ↑ John Bradshaw (15 August 2013). Cat Sense: The Feline Enigma Revealed. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 36–7. ISBN 978-0-241-96046-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Felis silvestris silvestris. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Felis silvestris silvestris |

- Wildcat Haven

- Species portrait European wildcat; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

- Save the Scottish Wildcat, general information and education website for Scottish wildcats.

- Electric Scotland: Scottish Wildcats

- Kreiszeitung: Wildkatzen rücken nach Norden vor (Wildcats Reach The North) (German)