West Prussia

| Province of West Prussia Provinz Westpreußen | ||||||

| Province of Prussia | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

.svg.png) | ||||||

| Capital | Marienwerder (1773–1793, 1806–1813) Danzig (1793–1806, 1813–1919) | |||||

| History | ||||||

| • | Established | 1773 | ||||

| • | Division by Napoleon | 1806 | ||||

| • | Restored | 1815 | ||||

| • | Province of Prussia | 1824–1878 | ||||

| • | Treaty of Versailles | 1919 | ||||

| • | Disestablished | 1922 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | 1890 | 25,534 km2 (9,859 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 1890 | 1,433,681 | ||||

| Density | 56.1 /km2 (145.4 /sq mi) | |||||

| Political subdivisions | Danzig Marienwerder | |||||

| Today part of | ||||||

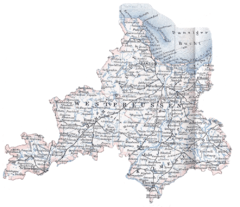

The Province of West Prussia (German: Provinz Westpreußen; Kashubian: Zôpadné Prësë; Polish: Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1922. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1773, formed from Royal Prussia of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth annexed in the First Partition of Poland. West Prussia was dissolved in 1829 and merged with East Prussia to form the Province of Prussia, but was re-established in 1878 when the merger was reversed and became part of the German Empire. From 1918, West Prussia was a province of the Free State of Prussia within Weimar Germany, losing most of its territory to the Second Polish Republic and the Free City of Danzig in the Treaty of Versailles. West Prussia was dissolved in 1922, and its remaining western territory was merged with Posen to form Posen-West Prussia, and its eastern territory merged with East Prussia as the Region of West Prussia district.

West Prussia's provincial capital alternated between Marienwerder (present-day Kwidzyn, Poland) and Danzig (Gdańsk, Poland) during its existence.

West Prussia was notable for its ethnic and religious diversity due to immigration and cultural changes, with the population becoming mixed over the centuries. Since the Middle Ages the region was inhabited by numerous Slavic and Baltic peoples, such as Pomeranians in the Pomerelia region, Old Prussians and Masovians in Kulmerland, and Pomesanians east of the Vistula River. Germans became the largest group in West Prussia by the 19th century, with large numbers of Kashubians, Poles, Slovincians, Huguenots, Mennonites, and Jews also settling in the region.

History

Context

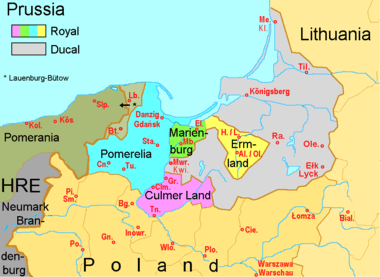

In the Thirteen Years' War (1454–1466), the towns of the Prussian Confederation in Pomerelia and the adjacent Prussian region east of the Vistula River rebelled against the rule of the Teutonic Knights and sought the assistance of King Casimir IV Jagiellon of Poland. By the Second Peace of Thorn in 1466, Pomerelia and the Prussian Culm (Chełmno) and Marienburg (Malbork) lands as well as the autonomous Prince-Bishopric of Warmia (Ermland) became the Polish province of Royal Prussia, which received special rights, especially in Danzig (Gdańsk). The province became a Land of the Polish Crown within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) by the 1569 Union of Lublin.

East Prussia around Königsberg, on the other hand, remained with the State of the Teutonic Knights, who were reduced to vassals of the Polish kings. Their territory was secularised to the Duchy of Prussia according to the 1525 Treaty of Kraków. Ruled in personal union with the Imperial Margraviate of Brandenburg from 1618, the Hohenzollern rulers of Brandenburg-Prussia were able to remove the Polish suzerainty by the 1657 Treaty of Wehlau. This development turned out to be fatal to the Polish monarchy, as the two parts of the rising Kingdom of Prussia were separated by Polish land.

Establishment

In the 1772 First Partition of Poland the Prussian king Frederick the Great took the occasion to annex most of Royal Prussia. The addition gave Prussia a land connection between the Province of Pomerania and East Prussia, cutting off the Polish access to the Baltic Sea and rendering East Prussia more readily defensible in the event of war with the Russian Empire. The annexed voivodeships of Pomerania (i.e. Pomerelia) except for the City of Danzig, Marienburg (Polish: Malbork) and Kulm (Polish: Chełmno) (except for Thorn; Polish: Toruń) were incorporated into the Province of West Prussia the following year, while Ermland (Polish: Warmia) became part of the Province of East Prussia. Further annexed areas of Greater Poland and Kuyavia in the south formed the Netze District. The Partition Sejm ratified the cession on 30 September 1773. Thereafter Frederick styled himself "King of Prussia" rather than "King in Prussia."

The Polish administrative and legal code was replaced by the Prussian system, and 750 schools were built from 1772-1775.[1] Both Protestant and Roman Catholic teachers taught in West Prussia, and teachers and administrators were encouraged to be able to speak both German and Polish. Frederick II of Prussia also advised his successors to learn Polish, a policy followed by the Hohenzollern dynasty until Frederick III decided not to let William II learn Polish.[1] Despite this, Frederick II (Frederick the Great) looked askance upon many of his new citizens. In a letter from 1735, he calls them "dirty" and "vile apes"[2] He had nothing but contempt for the szlachta, the numerous Polish nobility, and wrote that Poland had "the worst government in Europe with the exception of Ottoman Empire".[3] He considered West Prussia less civilized than Colonial Canada[4] and compared the Poles to the Iroquois.[3] In a letter to his brother Henry, Frederick wrote about the province that "it is a very good and advantageous acquisition, both from a financial and a political point of view. In order to excite less jealousy I tell everyone that on my travels I have seen just sand, pine trees, heath land and Jews. Despite that there is a lot of work to be done; there is no order, and no planning and the towns are in a lamentable condition."[5] Frederick invited German immigrants to redevelop the province,.[1][6] Many German officials also regarded the Poles with contempt.[4] According to the Polish historian Jerzy Surdykowski, Frederick the Great introduced 300,000 German colonists.[7] According to Christopher Clark, 54 percent of the annexed area's and 75 percent of the urban population were German-speaking Protestants.[8] Further Polish areas were annexed in the Second Partition of Poland in 1793, now including the cities of Danzig (Gdańsk) and Thorn (Toruń). Some of the areas of Greater Poland annexed in 1772 that formed the Netze District were added to West Prussia in 1793 as well.

After the defeat of Prussia by the Napoleonic French Empire at the 1806 Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, West Prussia lost its southern territory in the vicinity of Thorn and Culm (Chełmno) to the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw, it also lost Danzig, which was a Free City from 1807 until 1814. After the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Danzig, Kulm, and Thorn were returned to West Prussia by resolution of the Vienna Congress.

Restoration

In 1815, the province was administratively subdivided into the Regierungsbezirke Danzig and Marienwerder. From 1824-1878 West Prussia was combined with East Prussia to form the Province of Prussia, after which they were reestablished as separate provinces. In 1840, King Frederick William IV of Prussia sought to reconcile the state with the Catholic Church and the kingdom's Polish subjects by granting amnesty to imprisoned Polish bishops and re-establishing Polish instruction in schools in districts having Polish majorities. However, after the region became part of the German Empire in 1871 during the unification of Germany, it was subjected to measures aimed at Germanization of Polish-speaking areas.

The Polish historian Andrzej Chwalba cites Germanization measures that included:

- Ethnic Germans were favoured in government contracts and only they won them, while Poles always lost.[9]

- Ethnic Germans were also promoted in investment plans, supply contracts.[9]

- German craftsmen in Polish territories received the best locations in cities from authorities so that they could start their own business and prosper.[9]

- Soldiers received orders that banned them from buying in Polish shops and from Poles under the threat of arrest.[9]

- German merchantmen were encouraged to settle in Polish territories.[9]

- Tax incentives and beneficial financial arrangements were proposed to German officials and clerks if they would settle in Polish inhabited provinces.[9]

In the German census of 1910, the population of West Prussia was put at just over 1.7 million, of whom 65 percent listed their first language as German, 28 percent Polish and 7 percent Kashubian.

Dissolution

After the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, most of West Prussia was granted to the Second Polish Republic (the Polish Corridor) or the Free City of Danzig, while small parts in the west and east of the former province remained in Weimar Germany. The western remainder formed Posen-West Prussia in 1922, while the eastern remainder became part of Regierungsbezirk West Prussia within East Prussia.

The region was included in the Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia within Nazi Germany during World War II and settled with 130,000 German colonists,[10] while between 120,000 and 170,000 Poles and Jews were ethnically cleansed by the Germans.[11] As in all other areas, Poles and Jews were classified as "Untermenschen" by the German state, with their fate being slavery and extermination. Later in the war, many West Prussian Germans fled westward as the Red Army advanced on the Eastern Front. All of the areas occupied by Nazis were restored to Poland according to the post-war Potsdam Agreement in 1945, along with further neighbouring areas of former Nazi Germany. The vast majority of the remaining German population of the region which had not fled before was subsequently expelled westward. Many German civilians were deported to labor camps like Vorkuta in the Soviet Union, where a large number of them perished or were later reported missing. In 1949, the refugees established the non-profit Landsmannschaft Westpreußen to represent West Prussians in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Historical population

Legend for the districts:

Perhaps the earliest estimations on ethnic or national structure of West Prussia are from 1819. At that time West Prussia had 630,077 inhabitants, including 327,300 Poles (52%), 290,000 Germans (46%) and 12,700 Jews (2%).[13]

| Ethnic group | Population (number) | Population (percent) |

|---|---|---|

| Poles (Polen) | 327,300 | 52% |

| Germans (Deutsche) | 290,000 | 46% |

| Jews (Juden) | 12,700 | 2% |

| Total | 630,077 | 100% |

1 Estimated numbers. The first Prussian census asking about language was done in 1861

Karl Andree, "Polen: in geographischer, geschichtlicher und culturhistorischer Hinsicht" (Leipzig 1831), gives the total population of West Prussia as 700,000 - including 50% Poles (350,000), 47% Germans (330,000) and 3% Jews (20,000).[14]

The population more than doubled during the next seven decades, reaching 1,433,681 inhabitants (including 1,976 foreigners) in 1890. From 1885 to 1890 West Prussia's population decreased by 1%.

- 1875 - 1,343,057

- 1880 - 1,405,898

- 1890 - 1,433,681 (717,532 Catholics, 681,195 Protestants, 21,750 Jews, others)

- 1900 - 1,563,658 (800,395 Catholics, 730,685 Protestants, 18,226 Jews, others)

- 1905 - 1,641,936 (including 437,916 Polish speakers, 99,357 Kashubian speakers)[15]

According to the official German census of 1910, in the areas that became Polish after 1918, 42 percent of the populace were ethnic German in 1910 (including German military, civil clerks, and settlers).[16]

Contemporary sources in late 19th and early 20th centuries gave the number of Kashubians between 80,000–200,000.[17]

Subdivisions

Note: Prussian provinces were subdivided into districts called "Kreise" (singular "Kreis", abbreviated "Kr."). Cities would have their own "Stadtkreis" (urban district) and the surrounding rural area would be named for the city, but referred to as a "Landkreis" (rural district).

Population according to the German census 1905:

| Kreis (district) | Polish Name | Population 1905 | Polish, Kashubian | in Percent | German | in Percent |

| Regierungsbezirk Danzig | ||||||

| Elbing-Stadt | Elbląg | 55,627 | 175 | 0.31 | 55,328 | 99.46 |

| Elbing-Land | Elbląg | 38,871 | 105 | 0.27 | 38,737 | 99.66 |

| Marienburg | Malbork | 63,110 | 1,705 | 2.70 | 61,044 | 96.73 |

| Danzig-Stadt (City) | Gdańsk | 160,090 | 3,065 | 1.91 | 154,629 | 96.59 |

| Danzig-Niederung (lowland) | Gdańsk | 36,519 | 178 | 0.49 | 36,286 | 99.36 |

| Danziger Höhe (highland) | Gdańsk | 50,148 | 5,703 | 11.73 | 44,113 | 87.97 |

| Dirschau | Tczew | 40,856 | 15,144 | 37.07 | 25,466 | 62.33 |

| Preußisch Stargard | Starogard Gdański | 62,465 | 44,809 | 71.73 | 17,425 | 27.90 |

| Berent | Kościerzyna | 53,726 | 29,898 | 55.65 | 23,515 | 43.77 |

| Karthaus | Kartuzy | 66,612 | 46,281 | 69.48 | 20,203 | 30.33 |

| Neustadt | Wejherowo | 55,587 | 27,358 | 49.22 | 27,048 | 48.66 |

| Putzig | Puck | 25,701 | 17,906 | 69.67 | 7,629 | 29.68 |

| Regierungsbezirk Marienwerder | ||||||

| Stuhm | Sztum | 36,559 | 13,473 | 36.85 | 22,550 | 61.68 |

| Marienwerder | Kwidzyn | 68,096 | 24,541 | 36.04 | 42,699 | 62.70 |

| Rosenberg | Susz | 53,293 | 3,465 | 6.50 | 49,304 | 92.51 |

| Löbau | Lubawa | 57,285 | 45,510 | 79.44 | 11,368 | 19.84 |

| Strasburg | Brodnica | 59,927 | 38,507 | 64.26 | 21,008 | 35.06 |

| Briesen | Wąbrzeźno | 47,542 | 25,415 | 53.46 | 21,688 | 45.62 |

| Thorn-Stadt (City) | Toruń | 43,658 | 13,988 | 32.04 | 29,230 | 66.59 |

| Thorn-Land | Toruń | 58,765 | 30,833 | 52.47 | 27,508 | 46.81 |

| Kulm | Chełmno | 49,521 | 25,659 | 51.89 | 23,521 | 47.50 |

| Graudenz-Stadt (City) | Grudziądz | 39,953 | 4,421 | 11.07 | 30,709 | 76.86 |

| Graudenz-Land | Grudziądz | 46,509 | 19,331 | 41.56 | 26,888 | 57.81 |

| Schwetz | Świecie | 87,151 | 47,779 | 54.82 | 39,276 | 45.07 |

| Tuchel | Tuchola | 30,803 | 20,540 | 66.68 | 9,925 | 32.22 |

| Konitz | Chojnice | 59,694 | 32,704 | 54.79 | 26,581 | 44.50 |

| Schlochau | Człuchów | 66,317 | 10,180 | 15.35 | 55,981 | 84.41 |

| Flatow | Złotów | 67,783 | 18,002 | 26.56 | 49,167 | 72.54 |

| Deutsch Krone | Wałcz | 63,706 | 653 | 1.03 | 62,977 | 98.86 |

Office holders

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Koch, p. 136

- ↑ Przegląd humanistyczny, Tom 22, Wydania 3–6 Jan Zygmunt Jakubowski Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe, 2000, page 105

- 1 2 Ritter, p. 192

- 1 2 David Blackbourn. "Conquests from Barbarism": Interpreting Land Reclamation in 18th Century Prussia. Harvard University. Accessed 24 May 2006.

- ↑ MacDonogh, p. 363

- ↑ Norbert Finszch and Dietmar Schirmer. Identity and Intolerance: Nationalism, Racism, and Xenophobia in Germany and the United States. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-521-59158-9

- ↑ Duch Rzeczypospolitej Jerzy Surdykowski - 2001 Wydawn. Nauk. PWN, 2001, page 153

- ↑ Christopher M. Clark (2006). Iron Kingdom: the rise and downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947. Harvard University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-674-02385-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Andrzej Chwalba - Historia Polski 1795-1918 pages 461-463

- ↑ Bogdan Chrzanowski: Wypędzenia z Pomorza. Biuletyn IPN nr 5/2004, May 2004.

- ↑ WYSIEDLENIA Z ZIEM ZACHODNICH RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ W OKRESIE OKUPACJI NIEMIECKIEJ doctor Andrzej Gąsiorowski Stutthof Museum

- ↑ A history of eastern Europe: crisis and change Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries page 180, Routledge; 1st edition 1998 ""It systematically Germanicized "eastern" place names and public signs, fostered German cultural imperialism, and provided financial and other inducements for German farmers, officials, clergy, and teachers to settle and work in the east. After Bismarck's fall in 1890, Kaiser Wilhelm II actively encouraged all this. Not only did he provide large benefactions..."

- 1 2 Hassel, Georg (1823). Statistischer Umriß der sämmtlichen europäischen und der vornehmsten außereuropäischen Staaten, in Hinsicht ihrer Entwickelung, Größe, Volksmenge, Finanz- und Militärverfassung, tabellarisch dargestellt; Erster Heft: Welcher die beiden großen Mächte Österreich und Preußen und den Deutschen Staatenbund darstellt. Verlag des Geographischen Instituts Weimar. p. 42.

- ↑ Karl Andree: Polen: in geographischer, geschichtlicher und culturhistorischer Hinsicht, Leipzig 1831

- ↑ Zeno. "Westpreußen". www.zeno.org. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ http://web.ku.edu/~eceurope/hist557/lect11_files/11pic2.jpg

- ↑ Kilka słów o Kaszubach i ich mowie (in Polish)

References

- Blanke, Richard (1993). Orphans of Versailles. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 316. ISBN 0-8131-1803-4.

- Koch, H. W. (1978). A History of Prussia. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 326. ISBN 0-88029-158-3.

- MacDonogh, Giles (2001). Frederick the Great: A Life in Deed and Letters. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 436. ISBN 0-312-27266-9.

- Ritter, Gerhard (1974). Frederick the Great: A Historical Profile. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-520-02775-2.

- de Zayas, Alfred-Maurice (1994). A Terrible Revenge: The Ethnic Cleansing of the Eastern European Germans 1944-1950. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Rota, Andrea (2010). Wiedersehen mit der Familie, Wiedersehen in der Heimat. SÖHNE von Volker Koepp. In Elena Agazzi, Erhard Schütz (Ed.): Heimkehr: eine zentrale Kategorie der Nachkriegszeit. Geschichte, Literatur und Medien. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. p. 257-268. ISBN 978-3-428-53379-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Prussia. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article West Prussia. |