Prostitution in the United States

Prostitution is illegal in the vast majority of the United States as a result of state laws rather than federal laws. It is, however, legal in some rural counties within the state of Nevada. Prostitution nevertheless occurs throughout the country.

The regulation of prostitution in the country is not among the enumerated powers of the federal government. It is therefore exclusively the domain of the states to permit, prohibit, or otherwise regulate commercial sex under the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, except insofar as Congress may regulate it as part of interstate commerce with laws like the Mann Act. In most states, prostitution is considered a misdemeanor in the category of public order crime–crime that disrupts the order of a community. Prostitution was at one time considered a vagrancy crime.

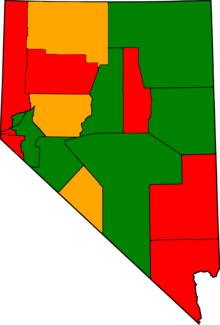

Currently, Nevada is the only U.S. jurisdiction to allow legal prostitution – in the form of regulated brothels – the terms of which are stipulated in the Nevada Revised Statutes. Only eight counties currently contain active brothels. All forms of prostitution are illegal in Clark County (which contains the Las Vegas–Paradise metropolitan area), Washoe County (which contains Reno), Carson City, Douglas County, and Lincoln County. The other counties theoretically allow brothel prostitution, but some of these counties currently have no active brothels. Street prostitution, "pandering", and living off of the proceeds of a prostitute remain illegal under Nevada law, as is the case elsewhere in the country.

According to the National Institute of Justice, a study conducted in 2008 found that approximately 15-20 percent of men in the country have engaged in commercial sex.[1]

As with other countries, prostitution in the U.S. can be divided into three broad categories: street prostitution, brothel prostitution, and escort prostitution.

History

18th century

Some of the women in the American Revolution who followed the Continental Army served the soldiers and officers as sexual partners. Prostitutes were a worrisome presence to army leadership, particularly because of the possible spread of venereal diseases. Some army officers, however, encouraged the presence of prostitutes during the Civil War to keep troop morale high. In August 20, 1863, the U.S. military commander Brig. General Robert S. Granger legalized prostitution in Nashville, Tennessee, in order to curb venereal disease among Union soldiers. The move was successful and venereal disease rates fell from forty percent to just four percent due to a stringent wellness program which required all prostitutes to register and be checked by a board certified physician every two weeks for which they were charged five dollars registration fee plus 50 cents per examination.[2]

19th century

In the 19th century, parlor house brothels catered to upper class clientele, while bawdy houses catered to the lower class. At concert saloons, men could eat, listen to music, watch a fight, or pay women for sex. Over 200 brothels existed in lower Manhattan. Prostitution was illegal under the vagrancy laws, but was not well-enforced by police and city officials, who were bribed by brothel owners and madams. Attempts to regulate prostitution were struck down on the grounds that regulation would be counter to the public good. Seventy-five percent of New York men had some type of sexually transmitted disease.[3]

The gold rush profits of the 1840s to 1900 attracted gambling, crime, saloons, and prostitution to the mining towns of the wild west. Julia Bulette was a leading madam in Virginia City, Nevada who was murdered in 1867. Widespread media coverage of prostitution occurred in 1836, when famous courtesan Helen Jewett was murdered, by one of her customers. The Lorette Ordinance of 1857 prohibited prostitution on the first floor of buildings in New Orleans.[4] Nevertheless, prostitution continued to grow rapidly in the U.S., becoming a $6.3 million business in 1858, more than the shipping and brewing industries combined.

By the U.S. Civil War, Washington's Pennsylvania Avenue had become a disreputable slum known as Murder Bay, home to an extensive criminal underclass and numerous brothels. So many prostitutes took up residence there to serve the needs of General Joseph Hooker's Army of the Potomac that the area became known as "Hooker's Division." Two blocks between Pennsylvania and Missouri Avenues became home to such expensive brothels that it was known as "Marble Alley."[5]

In 1873, Anthony Comstock created the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, an institution dedicated to supervising the morality of the public. Comstock successfully influenced the United States Congress to pass the Comstock Law, which made illegal the delivery or transport of "obscene, lewd, or lascivious" material and birth control information. In 1875, Congress passed the Page Act of 1875 that made it illegal to transport women into the nation to be used as prostitutes.[6]

In 1881, the Bird Cage Theatre opened in Tombstone, Arizona. It included a brothel in the basement and 14 cribs suspended from the ceiling, called cages. Famous men such as Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson, Diamond Jim Brady, and George Hearst frequented the establishment.

In the late 19th century, newspapers reported that 65,000 white slaves existed. Around 1890, the term "red-light district" was first recorded in the United States. From 1890 to 1982, the Dumas Brothel in Montana was America's longest-running house of prostitution.

New Orleans city alderman Sidney Story wrote an ordinance in 1897 to regulate and limit prostitution to one small area of the city, "The District", where all prostitutes in New Orleans must live and work. The District, or Storyville, became the most famous area for prostitution in the nation. Storyville at its peak had some 1500 prostitutes and 200 brothels.

20th century

Legal measures

In 1908, The Bureau of Investigation (BOI) was founded by the government to investigate "white slavery" by interviewing brothel employees to find out if they had been kidnapped. Out of 1106 prostitutes interviewed in one city, six said they were victims of white slavery. (In 1935, the BOI became the FBI.) The White-Slave Traffic Act (Mann Act) of 1910 prohibited so-called white slavery. It also banned the interstate transport of females for "immoral purposes". Its primary stated intent was to address prostitution and perceived immorality. The Supreme Court later included consensual debauchery, adultery, and polygamy under "immoral purposes".

Prior to World War I, there were few laws criminalizing prostitutes or the act of prostitution.[7]

During World War I, the U.S. government developed a public health program called the American Plan which authorized the military to arrest any woman within five miles of a military cantonment. If found infected, a woman could be sentenced to a hospital or a "farm colony" until cured. By the end of the war 15,520 prostitutes had been imprisoned, most never having received medical hospitalization.[8]

In 1918, the Chamberlain-Kahn Act which implemented the American Plan,[9] gave the government the power to quarantine any woman suspected of having a sexually transmitted disease (STD). A medical examination was required, and if it revealed an STD, this discovery could constitute proof of prostitution. The purpose of this law was to prevent the spread of venereal diseases among U.S. soldiers.[10] During World War I, Storyville was shut down to prevent VD transmission to soldiers in nearby army and navy camps.

The National Venereal Disease Control Act, which became effective July 1, 1938, authorized the appropriation of federal funds to assist the states in combating venereal diseases. Appropriations under this act were doubled after the United States entered the war. The May Act,3 which became effective with its signature by the President, July 11, 1941, armed the federal government with authority to suppress commercialized vice in the neighborhood of military camps and naval establishments in the United States.

The May Act, which became law in June 1941, intended to prevent prostitution on restricted zones around military bases. It was invoked chiefly during wartime. See World War II U.S. Military Sex Education.

Mortensen vs. United States, in 1944, ruled that prostitutes could travel across state lines, if the purpose of travel was not for prostitution.[11]

In 1967, New York City eliminated license requirements for massage parlors. Many massage parlors became brothels.[12] In 1970, Nevada began regulation of houses of prostitution. In 1971, the Mustang Ranch became Nevada's first licensed brothel, eventually leading to the legalization of brothel prostitution in 10 of 17 counties within the state. In time, Mustang Ranch became Nevada's largest brothel, with more revenue than all other legal Nevada brothels combined.

Other developments

In 1917, New Orleans government shut down prostitute cribs.[13] On January 25, 1917, an anti-prostitution drive in San Francisco attracted huge crowds to public meetings. At one meeting attended by 7,000 people, 20,000 were kept out for lack of room. In a conference with Reverend Paul Smith, an outspoken foe of prostitution, 300 prostitutes made a plea for toleration, explaining they had been forced into the practice by poverty. When Smith asked if they would take other work at $8 to $10 a week, the ladies laughed derisively, which lost them public sympathy. The police closed about 200 houses of prostitution shortly thereafter.[14]

In the early 20th century, widespread use of phones made call girls possible. This took prostitutes indoors and off the streets. They give their phone numbers on cards to customers. By World War II, prostitutes had increasingly gone underground as call girls.

Conditions for sex trade workers changed considerably in the 1960s. The combined oral contraceptive pill was first approved in 1960 for contraceptive use in the United States. "The Pill" helped prostitutes prevent pregnancy. In 1971, famous New York madame Xaviera Hollander wrote The Happy Hooker: My Own Story, a book that was notable for its frankness at the time, and considered a landmark of positive writing about sex. An early forerunner (1920s-1930s) of Xaviera Hollander's, both as a madam and author, was Polly Adler, whose bestselling book, A House Is Not a Home, was eventually adapted as a film also entitled A House is Not a Home. Carol Leigh, a prostitute's rights activist known as the "Scarlot Harlot," coined the term "Sex worker" in 1978. That same year, the Broadway musical The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas opened. It was based on the real-life Texas Chicken Ranch brothel. The play was the basis for the 1982 film starring Dolly Parton and Burt Reynolds.

COYOTE, formed in 1973, was the first prostitutes' rights group in the country. Other prostitutes' rights groups later formed, such as FLOP, HIRE, and PUMA.[15]

In 1997, "Hollywood Madam" Heidi Fleiss was convicted in connection with her prostitution ring with charges including pandering and tax evasion. Her ring had numerous famous and wealthy clients. Her original three-year sentence prompted widespread outrage at her harsh punishment, while her customers had not been punished. Earlier, in the 1980s, a member of Philadelphia's social elite, Sydney Biddle Barrows was revealed as a madam in New York City. She became known as the Mayflower Madam.

In 1990, U.S. Representative Barney Frank (D-MA) admitted to paying for sex in 1989. The House of Representatives voted to reprimand him.[16]

21st century

Ted Haggard, former leader of the National Association of Evangelicals, resigned in 2006 after he was accused of soliciting homosexual sex and methamphetamine.[17]

Randall L. Tobias, former Director of U.S. Foreign Assistance and U.S. Agency for International Development Administrator, resigned in 2007 after being accused of patronizing a Washington escort service.[18]

In 2007, U.S. Senator from Louisiana David Vitter acknowledged past transgressions after his name was listed as a client of "D.C. Madam" Deborah Jeane Palfrey's prostitution service in Washington.[19]

Eliot Spitzer resigned as governor of New York in 2008 amid threats of impeachment after news reports alleged he was a client of an international prostitution ring.[20]

In 2009, Rhode Island signed a bill into law making prostitution a misdemeanor. Prior to this law, between 1980 and 2009, Rhode Island was the only U.S. state where prostitution was decriminalized, as long as it was done indoors.[21] (See Prostitution in Rhode Island).

In 2014, due to the stagnant economy in Puerto Rico, the government considered legalizing prostitution.[22][23] In 2018, economist Robin Hanson suggested that the legalization of prostitution may solve the problem of inceldom.[24]

On April 11, 2018, the United States Congress passed the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act, commonly known as FOSTA-SESTA, which imposed severe penalties on online platforms that facilitated illicit sex work. The act shut down Backpage and lead to the arrest of its founders. The effectiveness of the bill has come into question as it has purportedly endangered sex workers and has been ineffective in catching and stopping sex traffickers.[25]

Types of prostitution

Red light districts

Although informal, red light districts can be found in some areas of the country, such as The Block in Baltimore. Since prostitution is illegal, there are no formal brothels, but massage parlors offering prostitution may be found along with street prostitution. Typically, these areas will also have other adult-oriented businesses, often due to zoning, such as strip clubs, sex shops, adult movie theaters, adult video arcades, peep shows, sex shows, and sex clubs.

Street prostitution

Street prostitution is illegal throughout the United States. Street prostitution tends to be clustered in certain areas known for solicitation. For instance, statistics on official arrests from the Chicago Police Department from August 19, 2005 to May 1, 2007, suggest that prostitution activity is highly concentrated: nearly half of all prostitution arrests occur in a tiny one-third of one percent of all blocks in the entire city of Chicago.[26]

A study of violence against women engaged in street prostitution found that 68% reported having been raped and 82% reported having been physically assaulted.[27]

A variation of street prostitution is that which occurs at truck stops along Interstate highways in rural areas. Called "lot lizards", these prostitutes solicit at truck stop parking lots and may use CB radios to communicate.

Escort or out-call prostitution

In spite of its illegality, escort prostitution exists throughout the United States from both independent prostitutes and those employed through escort agencies. Both freelancers and agencies may advertise under the term "bodywork" in the back of alternative newspapers, although some of these bodywork professionals are straightforward massage professionals.

The amount of money made by an escort differs depending on race, appearance, age, experience (e.g., pornography and magazine work), gender, services rendered, and location. Generally, male escorts command less on an hourly basis than women; white women quote higher rates than non-white women; and youth is at a premium. In the gay community, one escort agency in Washington, D.C., charges $150 an hour for male escorts and $250 an hour for transgender escorts. That agency takes $50 an hour from the escort. In larger metropolitan areas such as New York City, extremely attractive white American female escorts can charge $1,000–$2,000 per hour, with the agency taking 40%-50%.[28]

Typically, an agency will charge its escorts either a flat fee for each client connection or a percentage of the prearranged rate. In San Francisco, it is usual for typical heterosexual-market agencies to negotiate for as little as $100 up to a full 50% of a woman's reported earnings (not counting any gratuity received). Most transactions occur in cash, and optional tipping of escorts by clients in most major U.S. cities is customary but not compulsory. Credit card processing offered by larger scale agencies is often available for a service charge.[29]

Escorts and escort agencies have historically advertised through classified ads, yellow pages advertising, or word-of-mouth, but in more recent years, much of the advertising and soliciting of indoor prostitution has shifted to internet sites. Sites may represent individual escorts, agencies, or may run ads for many escorts. There are also a number of sites in which customers can discuss and post reviews of the sexual services offered by prostitutes and other sex workers. Many sites allow potential buyers to search for sex workers by physical characteristics and types of services offered.

Internet advertising of sexual services is offered not only by specialty sites, but in many cases by more mainstream advertising sites. Craigslist for many years featured an "adult services" section of this kind. After several years of pressure from law enforcement and anti-prostitution groups, Craigslist closed this section in September 2010, first for its U.S. pages, then some months later internationally. In January 2017, the "Adult" section of Backpage was closed down.[30]

Brothel prostitution

With the exception of some rural counties of Nevada, brothels are illegal in the United States. However, many massage parlors, saunas, spas, and similar otherwise-legal establishments serve as fronts for prostitution, especially in larger cities. Often, parlors are staffed by Asian immigrants and advertise in alternative newspapers and on sites like Craigslist and Backpage. They tend to have much longer working hours than parlors which are not actually brothels. They tend to be located in cities or along major highways.

Child prostitution

The prostitution of children in the United States is a serious concern[31][32] More than 100,000 children are reportedly forced into prostitution in the United States every year [33][34]

Legal status

Nevada is the only U.S. jurisdiction to allow some legal prostitution. Currently eight counties in Nevada have active brothels (these are all rural counties); as of February 2018, there are 21 brothels in Nevada.[35] Prostitution outside the licensed brothels is illegal throughout Nevada. Prostitution is illegal in the major metropolitan areas of Las Vegas, Reno, and Carson City, where most of the population lives; more than 90% of Nevada citizens live in a county where prostitution is illegal.

Prostitution in Rhode Island was outlawed in 2009. On November 3, governor Donald Carcieri signed into law a bill which makes the buying and selling of sexual services a crime.[21] Prostitution was legal in Rhode Island between 1980 and 2009 because there was no specific statute to define the act and outlaw it, although associated activities such as street solicitation, running a brothel and pimping were illegal.

Louisiana is the only state where convicted prostitutes are required to register as sex offenders. The State's crime against nature by solicitation law is used when a person is accused of engaging in oral or anal sex in exchange for money. Only prostitutes prosecuted under this law are required to be registered. This has led to a lawsuit filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights.[36]

The federal government also prosecutes some prostitution offenses. One man who forced women to be prostitutes received a 40-year sentence in federal court.[37] Another was prosecuted for income tax evasion.[38] Another man pleaded guilty to federal charges of harboring a 15-year-old girl and having her work as a prostitute.[39] Another federal defendant got life imprisonment for sex trafficking of a child by force.[40]

The ban on prostitution in the US has been criticized from a variety of viewpoints.[41]

Statistics on prostitutes and customers

One 1990 study estimated the annual prevalence of full-time equivalent prostitutes in the United States to be 23 per 100,000 population based on a capture–recapture study of prostitutes found in Colorado Springs, CO, police and sexually transmitted diseases clinic records between 1970 and 1988.[42]

A continuation of the Colorado Springs study[43] found a death rate among active prostitutes of 459 per 100,000 person-years, which is 5.9 times that for the (age and race adjusted) general population.

Among voluntary substance abuse program participants, 41.4% of women and 11.2% of men reported selling prostitution services during the last year (March 2008).[44]

In Newark, New Jersey, one report claims 57 percent of prostitutes are reportedly HIV-positive, and in Atlanta, 12 percent of prostitutes are possibly HIV-positive.[45]

A 2004 TNS poll reported 15 percent of all men have paid for sex and 30 percent of single men over age 30 have paid for sex.[46]

Over 200 men answered ads placed in Chicago area sex service classifieds for in depth interviews. Of these self-admitted "johns", 83% view buying sex as a form of addiction, 57% suspect that the women they paid were abused as children, and 40% said they are usually intoxicated when they purchase sex.[47]

The prostitution trade in the United States is estimated to generate $14 billion a year.[48] A 2012 report by Fondation Scelles indicated that there were an estimated 1 million prostitutes in the U.S.[49]

John schools

John schools are programs aimed towards the rehabilitation of purchasers of prostitution. In the first 12 years of the still ongoing program, now called the First Offender Prostitution Program, the recidivism rate amongst offenders was reduced from 8% to less than 5%. Since 1995, similar programs have been implemented in more than 40 other communities throughout the U.S., including Washington, D.C., West Palm Beach, FL, Buffalo, NY, Los Angeles, CA, and Brooklyn, NY. A 2009 audit of the first john school in San Francisco done by the city's budget analysis, faults the program with ill-defined goals and no way to determine its effectiveness. Despite being touted as a national model that comes at no cost to taxpayers, the audit said the program didn't cover its expenses in each of the last five years, leading to a $270,000 shortfall.[50]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prostitution in the United States. |

References

- ↑ "Percentage of Men (by Country) Who Paid for Sex at Least Once: The Johns Chart". ProCon.org. June 1, 2011.

- ↑ Serratore, Angela (July 8, 2013). "The Curious Case of Nashville's Frail Sisterhood". Smithsonian. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ XY factor, Prostitution: Sex in the City (History Channel)

- ↑ "Prostitution: Historical Timeline". ProCon.org. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ↑ Lowry, The Story the Soldiers Wouldn't Tell: Sex in the Civil War, 1994, p. 61-65.

- ↑ George Anthony Peffer, "Forbidden Families: Emigration Experiences of Chinese Women Under the Page Law, 1875-1882," Journal of American Ethnic History 6.1 (Fall 1986): 28-46. p.28.

- ↑ Melissa Gira Grant (February 18, 2013). "When Prostitution Wasn't a Crime: The Fascinating History of Sex Work in America". Alternet. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ↑ Ruth Rosen (1983). The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution in America, 1900-1918. JHU Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780801826658.

- ↑ Anne Cipriano Venzon, ed. (2013). The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 9781135684464.

- ↑ Ann Moseley; John J. Murphy; Robert Thacker, eds. (2017). Cather Studies. Volume 11: Willa Cather at the Modernist Crux. University of Nebraska Press. p. 175. ISBN 9780803296992.

- ↑ "Mortensen v. United States, 322 U.S. 369 (1944)". Justia Law. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "4 Groups Are Key Landlords For Midtown Sex Industry". The New York Times. July 10, 1977. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Storyville District - Stop 7 of 10 on the tour The Birthplace of Jazz: A Walking Tour Through New Orleans's Musical Past | New Orleans Historical". New Orleans Historical.

- ↑ San Francisco History - The Barbary Coast, Chapter 12. The End of The Barbary Coast Archived May 18, 2006, at Archive.is

- ↑ Bingham, Nicole (1998). "NEVADA SEX TRADE: A GAMBLE FOR THE WORKERS". Yale Journal of Law & Feminism. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "TV Movie Led to Prostitute's Disclosures". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Amid allegations, Haggard steps aside". Rocky Mountain News. November 2, 2006. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ↑ Glenn Kessler (April 28, 2007). "Rice Deputy Quits After Query Over Escort Service". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Scandal-linked senator breaks a week of silence". CNNPolitics.com. July 17, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ↑ "'Deeply sorry,' Spitzer to step down by Monday". CNNPolitics.com. March 12, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- 1 2 Arditi, Lynn (October 3, 2009). "Bill Signing Finally Outlaws Prostitution". Providence Journal. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Puerto Rico to legalize marijuana and prostitution". hightimes.com. April 23, 2014. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Prostitution Proponents in Puerto Rico". gardianlv.com. Apr 27, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ "We're talking about "sex robots" now. We've been here before". 2018-05-04.

- ↑ "Police Realizing That SESTA/FOSTA Made Their Jobs Harder; Sex Traffickers Realizing It's Made Their Job Easier".

- ↑ Chicago Booth. "Capital Ideas: Selected Papers on Chicago Price Theory - April 2009 - Trading Tricks". Chicagobooth.edu. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ↑ Farley, Melissa; Kelly, Vanessa (2008). "Prostitution". Women & Criminal Justice. 11 (4): 29–64. doi:10.1300/J012v11n04_04. ISSN 0897-4454.

- ↑ Celizic, Mike. "Former call girl opens up about the industry". TODAY.com. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Philadelphia female escorts service in New Jersey". Escorts Philadelphia. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ Hamilton, Matt. "Backpage shuts down adult section, citing government pressure and unlawful censorship campaign". latimes.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ↑ John Dankosky (April 17, 2013). Human Trafficking: Modern Day Slavery. Connecticut Public Radio. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ Eric M. Strauss (July 14, 2008). "Domestic Sex Trafficking in the U.S." ABC News. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ↑ Regehr, Roberts & Wolbert Burgess 2012, p. 230.

- ↑ "100,000 Children Are Forced Into Prostitution Each Year".

- ↑ "Nevada Brothel List". Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Nathan Koppel (February 16, 2011). "Louisiana's 'Crime Against Nature' Sex Law Draws Legal Fire". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "Sex Trafficking Ring Leader Sentenced to 40 Years in Prison - OPA - Department of Justice". justice.gov. 2011-03-24.

- ↑ Pankratz, Howard (September 16, 2010). "Owner of Denver Players prostitution service pleads guilty to tax evasion". Denver Post.

- ↑ "FBI — Brooklyn Man Pleads to Guilty to Forcing Underage Girls Into Prostitution in New York". Fbi.gov. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ↑ "FBI — Tea Man Sentenced to Life Imprisonment Plus 10 Years for Sex Trafficking of a Child by Force and Solicitation to Murder a Federal Witness". Minneapolis.fbi.gov. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ↑ German Lopez (18 August 2015). "The case for decriminalizing prostitution". Vox.

- ↑ Devon D. Brewer; John J. Potterat; Sharon B. Garrett; Stephen Q. Muth; John M. Roberts, Jr.; Danuta Kasprzyk; Daniel E. Montano; William W. Darrow (October 24, 2000). "Prostitution and the sex discrepancy in reported number of sexual partners" (pdf). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (22): 12385–12388. doi:10.1073/pnas.210392097. PMC 17351. PMID 11027304. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ↑ Potterat, J. J.; Brewer, D. D.; Muth, S. Q.; Rothenberg, R. B.; Woodhouse, D. E.; Muth, J. B.; Stites, H. K; Brody, S. (April 15, 2004). "Mortality in a Long-term Open Cohort of Prostitute Women". American Journal of Epidemiology. 159 (8): 778–785. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh110. PMID 15051587. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ ML Burnette, E Lucas, M Ilgen, Susan M. Frayne, J Mayo, JC Weitlauf "Prevalence and Health Correlates of Prostitution Among Patients Entering Treatment for Substance Use Disorders," in, Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol. 65 no. 3, page(s) 337-344

- ↑ "Prostitution: Not a Victimless Career Choice - Womens eNews". womensenews.org.

- ↑ Gary Langer, with Cheryl Arnedt and Dalia Sussman (October 21, 2004). "Primetime Live Poll: American Sex Survey". ABC News. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ↑ David Heinzmann (May 6, 2008). "Some men say using prostitutes is an addiction". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Prostitution Statistics – Facts about Prostitution and Latest News". havocscope.com.

- ↑ Gus Lubin (January 17, 2012). "There Are 42 Million Prostitutes In The World, And Here's Where They Live". Business Insider. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Audit faults S.F. D.A.'s prostitution program". SFGate. 2009-09-20.

- Regehr, Cheryl; Roberts, Albert R.; Wolbert Burgess, Ann (2012). Victimology: Theories and Applications. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1449665333.

Further reading

- Blackburn, George M., and Sherman L. Ricards. "The prostitutes and gamblers of Virginia City, Nevada: 1870." Pacific Historical Review 48.2 (1979): 239-258. online

- Best, Joel. "Careers in Brothel Prostitution: St. Paul, 1865-1883," Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 22 (1982), 597-619. online

- Blackman, Kayla. "Public power, private matters: The American Social Hygiene Association and the policing of sexual health in the Progressive era." (MA Thesis, University of Montana, 2014). online

- Butler, Anne M. Daughters of joy, sisters of misery: prostitutes in the American West, 1865-90 (University of Illinois Press, 1987).

- Clement, Elizabeth Alice. Love for Sale: Courting, Treating, and Prostitution in New York City, 1900-1945 (U of North Carolina Press, 2006). online

- Connelly, Mark Thomas. The Response to Prostitution in the Progressive Era (U of North Carolina Press, 1980). online

- Donovan, Brian. White Slave Crusades: Race, Gender, and Anti-vice Activism, 1887-1917 (U of Illinois Press, 2005)

- Goldman, Marion S. (1981). Gold Diggers & Silver Miners: Prostitution and Social Life on the Comstock Lode. U of Michigan Press. pp. passim. ISBN 978-0472063321.

- Hobson, Barbara Meil. Uneasy Virtue: The Politics of Prostitution and the American Reform Tradition (1987). online

- James, Ronald Michael, and C. Elizabeth Raymond, eds. Comstock women: the making of a mining community (U of Nevada Press, 1998).

- McNamara, Robert P. The Times Square Hustler: Male Prostitution in New York City (1994) online

- Pivar, David J. Purity and Hygiene: Women, Prostitution, and the "American Plan," 1900-1930 (Greenwood Press, 2002).

- Ringdal, Nils Johan. Love for sale: A world history of prostitution (Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 2007).

- Rosen, Ruth. The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution in America, 1900-1918 (Johns Hopkins U. Press, 1983).

- Spude, Catherine Holder. Saloons, Prostitutes, and Temperance in Alaska Territory (U of Oklahoma Press, 2015).

- Weitzer, Ronald. Legalizing Prostitution: From Illicit Vice to Lawful Business (2012) online

- West, Elliott. "Scarlet West: The oldest profession in the trans-Mississippi West." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 31.2 (1981): 16-27.