Nellie Bly

| Elizabeth Jane Cochran | |

|---|---|

Elizabeth Cochran, "Nellie Bly" | |

| Born |

Elizabeth Jane Cochran May 5, 1864 Cochran's Mills, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died |

January 27, 1922 (aged 57) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Journalist, novelist, inventor |

| Spouse(s) | Robert Seaman (m. 1895–1904, his death) |

| Awards | National Women's Hall of Fame (1998) |

| Signature | |

| |

| Notes | |

|

After her marriage, Bly used the name "Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman" as seen in the signatures on patents she filed. | |

Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman[1] (May 5, 1864[2] – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was an American journalist who was widely known for her record-breaking trip around the world in 72 days, in emulation of Jules Verne's fictional character Phileas Fogg, and an exposé in which she worked undercover to report on a mental institution from within.[3] She was a pioneer in her field, and launched a new kind of investigative journalism.[4] Bly was also a writer, industrialist, inventor, and a charity worker.

Early life

At birth she was named Elizabeth Jane Cochran. She was born in "Cochran's Mills", now part of the Pittsburgh suburb of Burrell Township, Armstrong County, Pennsylvania.[5][6][7] Her father, Michael Cochran, born about 1810, started out as a laborer and mill worker before buying the local mill and most of the land surrounding his family farmhouse. He later became a merchant, postmaster, and associate justice at Cochran's Mills (which was named after him) in Pennsylvania. Michael married twice. He had 10 children with his first wife, Catherine Murphy, and 5 more children, including Elizabeth, with his second wife, Mary Jane Kennedy.[8] Michael Cochran's father had immigrated from County Londonderry, Ireland in the 1790s.

As a young girl Elizabeth often was called "Pinky" because she so frequently wore that color. As she became a teenager she wanted to portray herself as more sophisticated, and so dropped the nickname and changed her surname to "Cochrane".[9] She attended boarding school for one term, but after her father's death in 1870 or 1871, was forced to drop out due to lack of funds.

In 1880 Cochrane's mother moved her family to Pittsburgh.[10] A newspaper column entitled "What Girls Are Good For" in the Pittsburgh Dispatch that reported that girls were principally for birthing children and keeping house prompted Elizabeth to write a response under the pseudonym "Lonely Orphan Girl".[11][10][12] The editor, George Madden, was impressed with her passion and ran an advertisement asking the author to identify herself. When Cochrane introduced herself to the editor, he offered her the opportunity to write a piece for the newspaper, again under the pseudonym "Lonely Orphan Girl".[12] Her first article for the Dispatch, entitled "The Girl Puzzle", was about how divorce affected women. In it, she argued for reform of divorce laws.[13] Madden was impressed again and offered her a full-time job.[10] It was customary for women who were newspaper writers at that time to use pen names. The editor chose "Nellie Bly", adopted from the title character in the popular song "Nelly Bly" by Stephen Foster.[14] Cochrane originally intended that her pseudonym be "Nelly Bly", but her editor wrote "Nellie" by mistake and the error stuck.[15]

Career

Pittsburgh Dispatch

As a writer Bly focused her early work for the Pittsburgh Dispatch on the lives of working women, writing a series of investigative articles on women factory workers. However, the newspaper soon received complaints from factory owners about her writing, and she was reassigned to women's pages to cover fashion, society, and gardening, the usual role for women journalists, and she became dissatisfied. She then traveled to Mexico to serve as a foreign correspondent. Still only 21, she spent nearly half a year reporting the lives and customs of the Mexican people; her dispatches later were published in book form as Six Months in Mexico.[13] In one report, she protested the imprisonment of a local journalist for criticizing the Mexican government, then a dictatorship under Porfirio Díaz.[16] When Mexican authorities learned of Bly's report, they threatened her with arrest, prompting her to flee the country. Safely home, she accused Díaz of being a tyrannical czar suppressing the Mexican people and controlling the press.[10]

Asylum exposé

Burdened again with theater and arts reporting, Bly left the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1887 for New York City. Penniless after four months, she talked her way into the offices of Joseph Pulitzer's newspaper the New York World, and took an undercover assignment for which she agreed to feign insanity to investigate reports of brutality and neglect at the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island.[17]

It was not an easy task for Nellie to be admitted to the Asylum. Nellie first decided to check herself into a boarding house called Temporary Homes for Females. She stayed up all night long to give herself the wide-eyed look of a disturbed woman, and began making accusations that the other boarders were crazy. Nellie told the assistant matron "“There are so many crazy people about, and one can never tell what they will do.” [18] Nellie refused to go to bed, and eventually scared so many of the other boarders that the police were called to take Nellie to the nearby courthouse. Once examined by a police officer, a judge, and a doctor, Nellie began her journey to Blackwell's Island. [19]

Committed to the asylum, Bly experienced the deplorable conditions firsthand. After ten days, the asylum released Bly at The World's behest. Her report, later published in book form as Ten Days in a Mad-House, caused a sensation, prompted the asylum to implement reforms, and brought her lasting fame.[1]

Around the world

In 1888 Bly suggested to her editor at the New York World that she take a trip around the world, attempting to turn the fictional Around the World in Eighty Days into fact for the first time. A year later, at 9:40 a.m. on November 14, 1889, and with two days' notice,[20] she boarded the Augusta Victoria, a steamer of the Hamburg America Line,[21] and began her 40,070 kilometer journey.

She took with her the dress she was wearing, a sturdy overcoat, several changes of underwear, and a small travel bag carrying her toiletry essentials. She carried most of her money (£200 in English bank notes and gold, as well as some American currency) in a bag tied around her neck.[22][23]

The New York newspaper Cosmopolitan sponsored its own reporter, Elizabeth Bisland, to beat the time of both Phileas Fogg and Bly. Bisland would travel the opposite way around the world, starting on the same day as Bly took off.[24][25] To sustain interest in the story, the World organized a "Nellie Bly Guessing Match" in which readers were asked to estimate Bly's arrival time to the second, with the Grand Prize consisting at first of a free trip to Europe and, later on, spending money for the trip.[23][26]

During her travels around the world, Bly went through England, France (where she met Jules Verne in Amiens), Brindisi, the Suez Canal, Colombo (Ceylon), the Straits Settlements of Penang and Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan. The development of efficient submarine cable networks and the electric telegraph allowed Bly to send short progress reports,[27] although longer dispatches had to travel by regular post and thus were often delayed by several weeks.[26]

Bly travelled using steamships and the existing railroad systems,[28] which caused occasional setbacks, particularly on the Asian leg of her race.[29] During these stops, she visited a leper colony in China[30][31] and, in Singapore, she bought a monkey.[30][32]

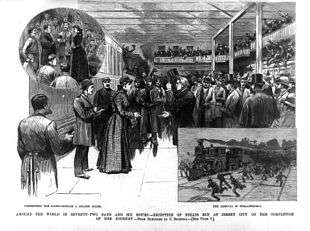

As a result of rough weather on her Pacific crossing, she arrived in San Francisco on the White Star Line ship RMS Oceanic on January 21, two days behind schedule.[29][33] However, after World owner Pulitzer chartered a private train to bring her home, she arrived back in New Jersey on January 25, 1890, at 3:51 pm.[27]

Just over seventy-two days after her departure from Hoboken, Bly was back in New York. She had circumnavigated the globe, traveling alone for almost the entire journey.[21] Bisland was, at the time, still crossing the Atlantic, only to arrive in New York four and a half days later. She also had missed a connection and had to board a slow, old ship (the Bothnia) in the place of a fast ship (Etruria).[20] Bly's journey was a world record, although it was bettered a few months later by George Francis Train, whose first circumnavigation in 1870 possibly had been the inspiration for Verne's novel. Train completed the journey in 67 days, and on his third trip in 1892 in 60 days.[34][35] By 1913, Andre Jaeger-Schmidt, Henry Frederick, and John Henry Mears had improved on the record, the latter completing the journey in fewer than 36 days.[36]

Later work

In 1904 Iron Clad began manufacturing the steel barrel that was the model for the 55-gallon oil drum still in widespread use in the United States. Although there have been spurious claims that Bly invented the barrel,[37] the actual inventor is Henry Wehrhahn. (U.S. Patents 808,327 and 808,413).[38]

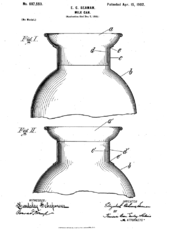

Bly was, however, an inventor in her own right, receiving U.S. Patent 697,553 for a novel milk can and U.S. Patent 703,711 for a stacking garbage can, both under her married name of Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman. For a time she was one of the leading women industrialists in the United States, but her negligence and embezzlement by a factory manager resulted in the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co. going bankrupt.[39] Back in reporting, she wrote stories on Europe's Eastern Front during World War I[40]. Nellie was actually the first woman and one of the first ever foreigners to visit the war zone between Serbia and Austria. She was even arrested when she was mistaken for a British spy.[41]

Ever the activist, Nellie notably covered the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913. Under the headline "Suffragists Are Men's Superiors", her parade story accurately predicted that it would be 1920 before women in the United States would be given the right to vote.[42]

Personal life and death

In 1895, Bly married millionaire manufacturer Robert Seaman.[43] Bly was 31 and Seaman was 73 when they married.[44] Due to her husband's failing health, she retired from journalism and succeeded her husband as head of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co., which made steel containers such as milk cans and boilers. In 1904, Seaman died.[37]

Bly died of pneumonia at St. Mark's Hospital in New York City in 1922 at age 57.[44] She was interred in a modest grave at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.[45]

Gallery

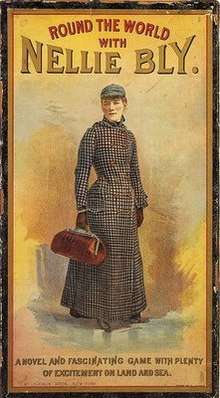

Cover of the 1890 board game Round the World with Nellie Bly

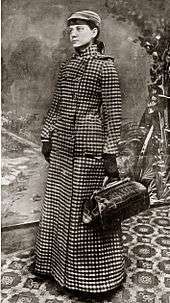

Cover of the 1890 board game Round the World with Nellie Bly Portrait of a 21-year-old Bly in Mexico

Portrait of a 21-year-old Bly in Mexico Nellie Bly in her later years

Nellie Bly in her later years- Bly's grave in Woodlawn Cemetery

Legacy

Dramatic representations

- Bly was the subject of the 1946 Broadway musical Nellie Bly, by Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen. The show ran for 16 performances.[46]

- Anne Helm appeared as Nellie Bly in the November 21, 1960, Tales of Wells Fargo TV episode "The Killing of Johnny Lash".

- In 1981, Linda Purl appeared as Bly in a made-for-television movie titled The Adventures of Nellie Bly.[47]

- Julia Duffy appeared as Bly in the July 10, 1983 Voyagers! episode "Jack's Back".

- In 1998, Lynn Schrichte wrote and toured a one-woman show about Nellie Bly titled Did You Lie, Nellie Bly?[48]

- A fictionalized account of Bly's around the world trip was used in the 2010 comic book Julie Walker is The Phantom published by Moonstone Books (Story: Elizabeth Massie, art: Paul Daly, colors: Stephen Downer).[49]

- Nellie Bly has been the subject of two episodes of the Comedy Central series Drunk History. The second-season episode "New York City" featured her undercover exploits in the Blackwell's Island asylum, with Bly being portrayed by Laura Dern.[50] The third-season episode "Journalism" starred Ellie Kemper as Bly and retold the story of her race around the world against Elizabeth Bisland (Natasha Leggero).[51]

- A fictionalized account of Bly's experience while committed is used as the basis for the 2013 horror novel Bedlam Stories by Pearry Reginald Teo and Christine Converse.[52]

- Bly is the protagonist of the 2014 historical murder mystery novel The New Colossus by Marshall Goldberg, published by Diversion Books.[53]

- A feature film by Pendragon Pictures titled 10 Days in a Madhouse after Bly's exposé was released on November 11, 2015. The film starring Caroline Barry, Christopher Lambert, Kelly Le Brock and Julia Chantrey depicts Bly's experiences on Blackwells Island.[54][55]

- Nellie is the protagonist of the 2015 novel by Dan Jorgensen titled And The Wind Whispered, published by Bygone Era Books.[56]

Eponyms and namesakes

- The Nellie Bly Amusement Park in Brooklyn, New York City, was named after her, taking as its theme Around the World in Eighty Days. The park reopened in 2007[58] under new management, renamed "Adventurers Amusement Park".[59]

- From early in the twentieth century until 1961, the Pennsylvania Railroad operated a parlor-car only express train between New York and Atlantic City that bore the name, Nellie Bly. The train was famously involved in a spectacular wreck in 1901, killing 17 people.[60]

- The New York Press Club confers an annual "Nellie Bly Cub Reporter" journalism award to acknowledge the best journalistic effort by an individual with three years or less professional experience.

- The board game Round the World with Nellie Bly created in 1890 is named in recognition of her trip.[61]

- Nellie Bly Kaleidoscope Shop[62] in Jerome, AZ, is the world's largest kaleidoscope shop.

- "Nelly Bly's Olde Tyme Ice Cream Parlour" is an ice cream shop and restaurant located in Riverton, New Jersey.[63]

- A fireboat named Nellie Bly operated in Toronto, Canada in the first decade of the 20th Century.[57]

Other recognition

- The character of Lois Lane is based on Bly

- In 1998 Bly was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[64]

- Bly was one of four journalists honored with a U.S postage stamp in a "Women in Journalism" set in 2002.[65][66]

- Bly's investigation of the Blackwell's Island insane asylum is dramatized in a 4-D film in the Annenberg Theater at the Newseum in Washington, D.C.

- Bly served as inspiration for the character Katherine Plumber from the musical adaptation of Disney's Newsies.[67]

- A fictionalized version of Bly as a mouse, named Nellie Brie, is a central character in An American Tail: The Mystery of the Night Monster.

- The character of Lana Winters (Sarah Paulson) in American Horror Story: Asylum is inspired by Bly's experience in the asylum.[68]

- The character of Maggie Dubois in The Great Race (1965) played by Natalie Wood is loosely inspired by Bly.[69]

- Author Carol McCleary has a series of mystery novels starring a fictionalized version of Bly.[70]

- In 2010 mystery writer Vicki Lane uses Bly's character to investigate twin mediums/spiritualists in the subplot of her novel, Under the Skin.[71]

- On May 5, 2015, the Google search engine produced an interactive "Google Doodle" for Bly; for the "Google Doodle" Karen O wrote, composed, and recorded an original song about Bly and Katy Wu created an animation set to Karen O's music.[72]

- Nellie Bly was a subject of Season 2 Episode 5 of The West Wing. First Lady Abbey Bartlet dedicated a memorial in Pennsylvania in honor of Nellie Bly and convinced the President to mention Addy and other female historic figures on his weekly radio address.[73]

- On the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, the character of Gillian Darmody uses the name pseudonym "Nellie Bly" and reads her book as an orphaned child.

See also

- Bicho de Sete Cabeças, 2001 Brazilian film about life in a mental hospital

- List of female adventurers

- Nellie Bly Cub Reporter Award

- Rosenhan experiment, 1970s, being sane in an insane place

- Winifred Bonfils, another pioneering woman journalist

References

- 1 2 DeMain, Bill. "Ten Days in a Madhouse: The Woman Who Got Herself Committed". mental floss. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- ↑ Kroeger 1994 reports (p. 529) that although a birth year of 1867 was deduced from the age Bly claimed to be at the height of her popularity, her baptismal record confirms 1864.

- ↑ "Five Reasons why a Google Doodle Tribute to Nellie Bly is justified". Biharprabha. May 5, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ↑ "American Experience". PBS.

- ↑ "Nellie Bly" (PDF). Pittsburgh Civic Light Opera. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Nellie Bly Historical Marker". Explore PA History. WITF-TV. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ Cridlebaugh, Bruce S. "Cochran's Mill Rd over Licks Run". Bridges and Tunnels of Allegheny County and Pittsburgh, PA. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ Kroeger 1994, p. 3.

- ↑ Kroeger 1994, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 Arthur Fritz. "Nellie Bly, (1864–1922)". Nellie Bly Online. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Young and Brave: Girls Changing History". National Woman's History Museum. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- 1 2 Jone Johnson Lewis. "Nellie Bly". About.com. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- 1 2 Simkin, John (September 1997). "Nellie Bly". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ Adrian Room (July 1, 2010). Dictionary of Pseudonyms: 13,000 Assumed Names and Their Origins, 5th ed. McFarland. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-7864-5763-2.

- ↑ Kroeger 1994, as excerpted at "Brooke Kroeger's Nellie Bly". New York Correction History Society. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ Bly, Nellie (1889). "

- ↑ Gregory, Alice (May 14, 2014). "Nellie Bly's Lessons in Writing What You Want To". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Ten Days in a Mad-House". digital.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ "Ten Days in a Mad-House". digital.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- 1 2 Ruddick 1999, p. 4.

- 1 2 Kroeger 1994, p. 146.

- ↑ Kroeger 1994, p. 141.

- 1 2 Ruddick 1999, p. 5.

- ↑ Barcousky, Len. "Eyewitness 1890: Pittsburgh welcomes home globe-trotting Nellie Bly", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 23, 2009, accessed January 30, 2011

- ↑ "Society Topics of the Week". The New York Times, November 24, 1889, accessed January 30, 2011

- 1 2 Kroeger 1994, p. 150.

- 1 2 Ruddick 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ Ruddick 1999, p. 6.

- 1 2 Bear, David. "Around the World With Nellie Bly." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 26, 2006

- 1 2 Ruddick 1999, p. 7.

- ↑ Kroeger 1994, p. 160.

- ↑ Kroeger 1994, p. 158.

- ↑ "Phineas Fogg Outdone". Daily Alta California. January 22, 1890. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ George Francis Train, The Bostonian Who Really Was Phileas Fogg at the New England Historical Society

- ↑ "William Lightfoot Visscher, Journal profile, part one". Skagitriverjournal.com. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ The New York Times, "A Run Around the World", August 8, 1913

- 1 2 "The Remarkable Nellie Bly". American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Industries – Business History of Oil Drillers, Refiners". Business History. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ Garrison, Jayne (March 28, 1994). "Nellie Bly, Girl Reporter : Daredevil journalist". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ↑ The remarkable Nellie Bly, inventor of the metal oil drum, Petroleum Age, 12/2006, p.5.

- ↑ "Nellie Bly - New World Encyclopedia". www.newworldencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ Harvey, Sheridan (2001). "Marching for the Vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913". American Women. Library of Congress. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Nellie Bly | American journalist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- 1 2 "Nellie Bly, journalist, Dies of Pneumonia". The New York Times. The New York Times Co. January 28, 1922. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ↑ Dunning, Jennifer (February 23, 1979). "Woodlawn, Bronx's Other Hall of Fame". The New York Times. The New York Times Co. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ↑ "After the poorly received Nellie Bly (1946) ... [stage director Edgar J.] MacGregor retired.", musicals101.com

- ↑ The Adventures of Nellie Bly at AllMovie

- ↑ "Lynn Schrichte". Resourceful Women. Library of Congress. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "024. Julie Walker: The Phantom (A)". Moonstonebooks.com. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Nellie Bly Goes Undercover at Blackwell's Island". Comedy Central. July 8, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Journalism". Comedy Central. October 20, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Bedlam Stories". Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ↑ "The New Colossus". diversionbooks.com/ebooks/new-colossus. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ↑ 10 Days in a Mad House, Website.

- ↑ STUDIES: Women still struggle in male-dominated film industry Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., Tom Henderson, Filmfiles.tv.

- ↑ Callison, Jill (March 23, 2015). "Author: There's gold in them thar southern Black Hills". USA Today. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- 1 2

Chris Bateman (2013). "The nautical adventures of the Trillium ferry in Toronto". Blog TO. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

A second fire boat, the Nellie Bly, presumably named after the American journalist famous for her round-the-world trip and expose piece of US mental health practices, was also involved. {'

Their combined efforts prevented the fire from spreading,' noted the Star. }} - ↑ "Adventurer's Amusement Park" UltimaterollerCoaster.com

- ↑ "Adventurer's Park Family Entertainment Center – 1824 Shore Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11214 – (718) 975–2748". adventurerspark.com.

- ↑ "Terrible Wreck On Pennsylvania Road" The Gloversville Daily Leader February 22, 1901

- ↑ "Round the world with Nellie Bly--The Worlds globe circler". Library of Congress. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Home". Nellie Bly Kaleidoscopes and Art Glass.

- ↑ "Catch the Scoop on Riverton's Old-Fashioned Ice Cream Shop". Moorestown, New Jersey Patch.

- ↑ "Elizabeth Jane Cochran – National Women's Hall of Fame". Greatwomen.org. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ USPS Press Release (September 14, 2002), Four Accomplished Journalists Honored on U.S. Postage Stamps, usps.com

- ↑ http://slideplayer.com/slide/9446515/

- ↑ "Being Katherine: An Interview with Newsies' Kara Lindsay". Oh My Disney. September 17, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ Eidell, Lynsey (October 7, 2015). "All the Real-Life Scary Stories Told on American Horror Story". Glamour. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ Vollen, Guy (July 20, 2016). "Forgotbusters: The Early Years | THE GREAT RACE and THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR FLYING MACHINES". The Solute. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Books". Carol McCleary. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ↑ Lane, Vicki (2010-01-28). "Vicki Lane Mysteries: Enter Nellie Bly". Vicki Lane Mysteries. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

- ↑ "What Girls are Good For: Happy birthday Nellie Bly". May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ↑ MacIntosh, Selena (July 2011). "Ladyghosts: The West Wing 2.05, "And It's Surely to Their Credit"". Persephone. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

Bibliography

- Affidavit of Beatrice K. Brown; Surrogates Court, Kings County (1922)

- Goodman, Matthew (2013). Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland's History-Making Race Around the World.

- Kroeger, Brooke (1994). Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0812925258.

- Ruddick, Nicholas (1999). "Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age". Canadian Review of American Studies. 29 (1).

External links

| Library resources about Nellie Bly |

| By Nellie Bly |

|---|

- Information, photos and original Nellie Bly articles at Nellie Bly Online

- Nellie Bly's collected journalism at The Archive of American Journalism

- Editions of Bly's books at the Celebration of Women Writers:

- American Experience | Around the World In 72 Days, a documentary about Bly's trip around the world

- Daily Alta California, January 22, 1890

- Norwood, Arlisha. "Nellie Bly". National Women's History Museum. 2017.

- The Daring Nellie Bly: America's Star Reporter illustrated biography by Bonnie Christensen, reviewed by Maria Popova

- Works by Nellie Bly at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Nellie Bly at Internet Archive

- Works by Nellie Bly at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)