Nattō

Nattō is often eaten on rice | |

| Course | Breakfast |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Japan |

| Main ingredients | Fermented soybeans |

Nattō (納豆) is a traditional Japanese food made from soybeans fermented with Bacillus subtilis var. natto.[1] Some eat it as a breakfast food.[2] It is served with soy sauce, karashi mustard and Japanese bunching onion. Nattō may be an acquired taste because of its powerful smell, strong flavor, and sticky, slimy texture.[3][4][5][6][7] In Japan, nattō is most popular in the eastern regions, including Kantō, Tōhoku, and Hokkaido.[8]

History

Sources differ about the earliest origin of nattō. One theory is that nattō was codeveloped in multiple locations in the distant past, since it is simple to make with ingredients and tools commonly available in Japan since ancient times.[9] There is also the story about Minamoto no Yoshiie, who was on a campaign in northeastern Japan between 1086 AD and 1088 AD, when one day, they were attacked while boiling soybeans for their horses. They hurriedly packed up the beans, and did not open the straw bags until a few days later, by which time the beans had fermented. The soldiers ate it anyway, and liked the taste, so they offered some to Yoshiie, who also liked the taste.[10]

A change in the production of nattō occurred in the Taishō period (1912–1926), when researchers discovered a way to produce a nattō starter culture containing Bacillus subtilis without the need for straw, thereby simplifying the commercial production of nattō and enabling more consistent results.[11]

Appearance and consumption

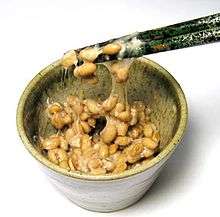

Nattō has a distinctive smell, somewhat akin to a pungent cheese. Stirring nattō produces lots of sticky strings.[1]

Nattō is occasionally used in other foods, such as nattō sushi, nattō toast, in miso soup, tamagoyaki, salad, as an ingredient in okonomiyaki, or even with spaghetti. Sometimes soybeans are crushed and fermented. This is called hikiwari nattō.

Many find the taste unpleasant and smelly while others relish it as a delicacy. Nattō is more popular in some areas of Japan than in others. Nattō is known to be popular in the eastern Kantō region, but less popular in Kansai. A 2009 Internet survey in Japan indicated 70.2% of respondents like nattō and 29.8% do not, but out of 29.8% who dislike nattō, about half of them eat nattō for its health benefits.[12]

Production process

Nattō is made from soybeans, typically nattō soybeans. Smaller beans are preferred, as the fermentation process will be able to reach the center of the bean more easily. The beans are washed and soaked in water for 12 to 20 hours to increase their size. Next, the soybeans are steamed for 6 hours, although a pressure cooker may be used to reduce the time. The beans are mixed with the bacterium Bacillus subtilis, known as nattō-kin in Japanese. From this point on, care must be taken to keep the ingredients away from impurities and other bacteria. The mixture is fermented at 40 °C (104 °F) for up to 24 hours. Afterward, the nattō is cooled, then aged in a refrigerator for up to one week to allow the development of stringiness.

In nattō-making facilities, these processing steps have to be done while avoiding incidents in which soybeans are touched by workers. Even though workers use B. subtilis natto as the starting culture, which can suppress some undesired bacterial growth, workers pay extra-close attention not to introduce skin flora on to soy beans.[13]

To make nattō at home, a bacterial culture of B. subtilis is needed. B. subtilis natto is weak in lactic acid, so it is important to prevent lactic acid bacteria from breeding. Some B. subtilis natto varieties that are closer to odorless are usually less active, raising the possibility that minor germs will breed. Bacteriophages are dangerous to B. subtilis.

Historically, nattō was made by storing the steamed soybeans in rice straw, which naturally contains B. subtilis natto. The soybeans were packed in straw and left to ferment.

End product

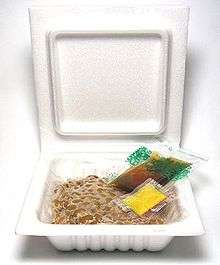

Today's mass-produced nattō is sold in small polystyrene containers. A typical package contains two, three, or occasionally four containers, each 40 to 50 g. One container typically complements a small bowl of rice.

Nattō has a different nutritional makeup from raw soy beans, losing Vitamin A and several other vitamins and minerals. The calorie content of nattō is lower than that of raw soy beans, however. While soy beans are highly nutritious, the nutrition is packed in the bean's hard fiber. Nattō includes the benefits of nutritious soy and softer dietary fiber without the high sodium content present in many other soy products, notably in miso. Nattō contains no cholesterol and is a significant source of iron, calcium, magnesium, protein, potassium, vitamins B6, B2, E, K2, and more.[14][15] When nattō is mixed with egg and eaten with rice, Japanese call the dish a perfectly nutritious meal, covering all nutritional needs. Nattō is the richest food source of natural K2. Consumption of it is strongly associated with bone health.[16]

When B. subtilis natto breaks up soy protein, the bacteria create chains of polyglutamic acid, gamma polyglutamic acid. This polypeptide chain is unusual in that the peptide bond is found between the nitrogen and the R-group's carboxyl acid.[17] Nattō gets its stringiness from the gamma polyglutamic acid. Its odor comes from diacetyl and pyrazines, but if it is allowed to ferment too long, then ammonia is released.[18]

Nutrition

By mass, nattō is 55% water, 18% protein, 11% fats, 5% fiber, and 5% sugars.[19]

A serving of nattō (100g) provides 29% of the Daily value (DV) of Vitamin K2, 22% of the DV for Vitamin C, 76% of the DV for manganese, 48% of the DV for iron, and 22% of the DV for dietary fiber.[20]

Close relatives of nattō

Many countries produce similar traditional soybean foods fermented with Bacillus subtilis, such as shuǐdòuchǐ (水豆豉) of China, cheonggukjang (청국장) of Korea, thuanao (ถั่วเน่า) of Thailand, kinema of Nepal and the Himalayan regions of West Bengal and Sikkim, tungrymbai of Meghalaya, hawaijaar of Manipur, bekang um of Mizoram, akhuni of Nagaland, and piak of Arunachal Pradesh, India.[8][21]

In addition, certain West African bean products are fermented with the bacillus, including dawadawa, sumbala, and iru, made from néré seeds or soybeans, and ogiri, made from sesame or melon seeds.

Gallery

A nattō bean-size legend using beans before fermentation in a supermarket

A nattō bean-size legend using beans before fermentation in a supermarket Nattō being stirred with chopsticks

Nattō being stirred with chopsticks Nattō gunkan maki (Nattō sushi)

Nattō gunkan maki (Nattō sushi) Nattō wrapped in rice straw, old-style nattō package

Nattō wrapped in rice straw, old-style nattō package

See also

- Amanattō – beans sweetened with sugar

- Shiokara – another sticky fermented Japanese seafood

- Oncom – Indonesian slimy fermented soy

- Okra – another slimy food common in the American South

- Corn smut

- Fermented bean paste

- Japanese cuisine – Other fermented soy foods include soy sauce, Japanese miso and fermented tofu.

- List of ancient dishes and foods

- List of fermented soy products

- List of soy-based foods

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- 1 2 Hosking, Richard (1995). A Dictionary of Japanese Food - Ingredients and Culture. Tuttle. p. 106. ISBN 0-8048-2042-2.

- ↑ McCloud, Tina (7 December 1992). "Natto: A Breakfast Dish That's An Acquired Taste". Daily Press. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

It is a traditional soybean breakfast food from northern Japan and it's called natto. [...] As a breakfast food, natto is usually served over steamed rice and mixed with mustard and soy sauce.

- ↑ Katz, Sandor Ellix (2012). The Art of Fermentation: An In-Depth Exploration of Essential Concepts and Processes from Around the World. Chelsea Green Publish. pp. 328–329. ISBN 978-1603582865.

Natto is a Japanese soy ferment that produces a slimy, mucilagenous coating on the beans, something like okra. [...] The flavor of natto carries notes of ammonia (like some cheeses or overripe tempeh), which gets stronger as it ferments longer.

- ↑ A., M. (30 March 2010). "Not the natto!". Asian Food. The Economist. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

... natto, a food that has achieved infamy among Japan's foreign residents.

- ↑ Buerk, Roland (11 March 2010). "Japan opens 98th national airport in Ibaraki". BBC News. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

... natto, a fermented soy bean dish that many consider an acquired taste.

- ↑ "Natto Fermented Soy Bean Recipe Ideas". Japan Centre. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

Natto are one of those classic dishes that people either love or hate. Like Marmite or blue cheese, natto has a very strong smell and intense flavour that can definitely be an acquired taste.

- ↑ "Preparing Nattou". Massahiro. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

Preparing Nattou step by step, without using rice straw.

- 1 2 Shurtleff, W.; Aoyagi, A (2012). History of Natto and Its Relatives (1405–2012). Lafayette, California: Soyinfo Center.

- ↑ Deutsch, Jonathan; Murakhver, Natalya (2012). They Eat That?: A Cultural Encyclopedia of Weird and Exotic Food from Around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-313-38058-7. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ↑ William Shurtleff; Akiko Aoyagi (2012). History of Natto and Its Relatives (1405–2012). Soyinfo Center. ISBN 978-1-928914-42-6.

- ↑ Kubo, Y; Rooney, A. P; Tsukakoshi, Y; Nakagawa, R; Hasegawa, H; Kimura, K (2011). "Phylogenetic Analysis of Bacillus subtilis Strains Applicable to Natto (Fermented Soybean) Production". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (18): 6463–6469. doi:10.1128/AEM.00448-11. PMC 3187134. PMID 21764950.

- ↑ "納豆が出来るまで。納豆の製造工程". Natto.in. 2004. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ "Soybean Nutrition Facts, Soybean Facts". Soy-beans.org. 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ "Natto – Nutritional Information". eLook.org. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ Kaneki M, Hodges SJ, Hosoi T, Fujiwara S, Lyons A, Crean SJ, Ishida N, Nakagawa M, Takechi M, Sano Y, Mizuno Y, Hoshino S, Miyao M, Inoue S, Horiki K, Shiraki M, Ouchi Y, Orimo H (2001). "Japanese fermented soybean food as the major determinant of the large geographic difference in circulating levels of K vitamins2: possible implications for hip-fracture risk". Nutrition. 17 (4): 315–321. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00554-2. PMID 11369171.

- ↑ "Google Translate". Translate.google.ca. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ Kada S, Yabusaki MY, Kaga T, Ashida H, Yoshida KI (2008). "Identification of Two Major Ammonia-Releasing Reactions Involved in Secondary Natto Fermentation" (PDF). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 72 (7): 1869–1876. doi:10.1271/bbb.80129. PMID 18603778.

- ↑ United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 27 Basic Report: 16113, Natto

- ↑ Natto nutritional values

- ↑ Arora, Dilip K.; Mukerji, K. G.; Marth, Elmer H., eds. (1991). Handbook of Applied Mycology Volume 3: Foods and Feeds. CRC Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-8247-8491-1.