Lectin

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins, macromolecules that are highly specific for sugar moieties of other molecules. Lectins perform recognition on the cellular and molecular level and play numerous roles in biological recognition phenomena involving cells, carbohydrates, and proteins.[1][2] Lectins also mediate attachment and binding of bacteria and viruses to their intended targets.

Lectins are ubiquitous in nature and are found in many foods. Some foods such as beans and grains need to be cooked or fermented to reduce lectin content. Some lectins are beneficial, such as CLEC11A which promotes bone growth, while others may be powerful toxins such as ricin.[3]

Lectins may be disabled by specific mono- and oligosaccharides, which bind to ingested lectins from grains, legume, nightshade plants and dairy; binding can prevent their attachment to the carbohydrates within the cell membrane.[4] The selectivity of lectins means that they are very useful for analyzing blood type, and they are also used in some genetically engineered crops to transfer traits, such as resistance to pests and resistance to herbicides.

Etymology

| Table of the major plant lectins [5] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lectin Symbol | Lectin name | Source | ligand motif | ||

| Mannose binding lectins | |||||

| ConA | Concanavalin A | Canavalia ensiformis | α-D-mannosyl and α-D-glucosyl residues branched α-mannosidic structures (high α-mannose type, or hybrid type and biantennary complex type N-Glycans) | ||

| LCH | Lentil lectin | Lens culinaris | Fucosylated core region of bi- and triantennary complex type N-Glycans | ||

| GNA | Snowdrop lectin | Galanthus nivalis | α 1-3 and α 1-6 linked high mannose structures | ||

| Galactose / N-acetylgalactosamine binding lectins | |||||

| RCA | Ricin, Ricinus communis Agglutinin, RCA120 | Ricinus communis | Galβ1-4GalNAcβ1-R | ||

| PNA | Peanut agglutinin | Arachis hypogaea | Galβ1-3GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr (T-Antigen) | ||

| AIL | Jacalin | Artocarpus integrifolia | (Sia)Galβ1-3GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr (T-Antigen) | ||

| VVL | Hairy vetch lectin | Vicia villosa | GalNAcα-Ser/Thr (Tn-Antigen) | ||

| N-acetylglucosamine binding lectins | |||||

| WGA | Wheat Germ Agglutinin, WGA | Triticum vulgaris | GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc, Neu5Ac (sialic acid) | ||

| N-acetylneuraminic acid binding lectins | |||||

| SNA | Elderberry lectin | Sambucus nigra | Neu5Acα2-6Gal(NAc)-R | ||

| MAL | Maackia amurensis leukoagglutinin | Maackia amurensis | Neu5Ac/Gcα2,3Galβ1,4Glc(NAc) | ||

| MAH | Maackia amurensis hemoagglutinin | Maackia amurensis | Neu5Ac/Gcα2,3Galβ1,3(Neu5Acα2,6)GalNac | ||

| Fucose binding lectins | |||||

| UEA | Ulex europaeus agglutinin | Ulex europaeus | Fucα1-2Gal-R | ||

| AAL | Aleuria aurantia lectin | Aleuria aurantia | Fucα1-2Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3/4)Galβ1-4GlcNAc, R2-GlcNAcβ1-4(Fucα1-6)GlcNAc-R1 | ||

W.C. Boyd introduced term 'lectin' in 1954 from Latin word 'choose'.[6]

History

Long before a deeper understanding of their numerous biological functions, the plant lectins, also known as phytohemagglutinins, were noted for their particular high specificity for foreign glycoconjugates (e.g. those of fungi, invertebrates, and animals)[7] and used in biomedicine for blood cell testing and in biochemistry for fractionation.

Although they were first discovered more than 100 years ago in plants, now lectins are known to be present throughout nature. It is generally believed that the earliest description of a lectin was given by Peter Hermann Stillmark in his doctoral thesis presented in 1888 to the University of Dorpat. Stillmark isolated ricin, an extremely toxic hemagglutinin, from seeds of the castor plant (Ricinus communis).

The first lectin to be purified on a large scale and available on a commercial basis was concanavalin A, which is now the most-used lectin for characterization and purification of sugar-containing molecules and cellular structures. The legume lectins are probably the most well-studied lectins.

Biological functions

Most lectins do not possess enzymatic activity. Lectins occur ubiquitously in nature. They may bind to a soluble carbohydrate or to a carbohydrate moiety that is a part of a glycoprotein or glycolipid. They typically agglutinate certain animal cells and/or precipitate glycoconjugates.

Functions in animals

Lectins serve many different biological functions in animals, from the regulation of cell adhesion to glycoprotein synthesis and the control of protein levels in the blood. They also may bind soluble extracellular and intercellular glycoproteins. Some lectins are found on the surface of mammalian liver cells that specifically recognize galactose residues. It is believed that these cell-surface receptors are responsible for the removal of certain glycoproteins from the circulatory system.

Another lectin is a receptor that recognizes hydrolytic enzymes containing mannose-6-phosphate, and targets these proteins for delivery to the lysosomes. I-cell disease is one type of defect in this particular system.

Lectins also are known to play important roles in the immune system. Within the innate immune system lectins such as the MBL, the mannose-binding lectin, help mediate the first-line defense against invading microorganisms. Other lectins within the immune system are thought to play a role in self-nonself discrimination and they likely modulate inflammatory and autoreactive processes.[8] Intelectins (X-type lectins) were shown to bind microbial glycans and may function in the innate immune system as well. Lectins may be involved in pattern recognition and pathogen elimination in the innate immunity of vertebrates including fishes.[9]

Functions in plants

The function of lectins in plants (legume lectin) is still uncertain. Once thought to be necessary for rhizobia binding, this proposed function was ruled out through lectin-knockout transgene studies.[10]

The large concentration of lectins in plant seeds decreases with growth, and suggests a role in plant germination and perhaps in the seed's survival itself. The binding of glycoproteins on the surface of parasitic cells also is believed to be a function. Several plant lectins have been found to recognize non-carbohydrate ligands that are primarily hydrophobic in nature, including adenine, auxins, cytokinin, and indole acetic acid, as well as water-soluble porphyrins. It has been suggested that these interactions may be physiologically relevant, since some of these molecules function as phytohormones.[11]

Functions in bacteria and viruses

It is hypothesized that some hepatitis C viral glycoproteins attach to C-type lectins on the host cell surface (liver cells) to initiate infection.[12] To avoid clearance from the body by the innate immune system, pathogens (e.g., virus particles and bacteria that infect human cells) often express surface lectins known as adhesins and hemagglutinins that bind to tissue-specific glycans on host cell-surface glycoproteins and glycolipids.[13]

Use in science, medicine, and technology

Use in medicine and medical research

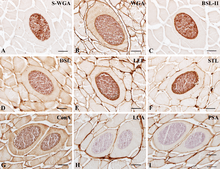

Purified lectins are important in a clinical setting because they are used for blood typing.[14] Some of the glycolipids and glycoproteins on an individual's red blood cells can be identified by lectins.

- A lectin from Dolichos biflorus is used to identify cells that belong to the A1 blood group.

- A lectin from Ulex europaeus is used to identify the H blood group antigen.

- A lectin from Vicia graminea is used to identify the N blood group antigen.

- A lectin from Iberis amara is used to identify the M blood group antigen.

- A lectin from coconut milk is used to identify Theros antigen.

- A lectin from Carex is used to identify R antigen.

In neuroscience, the anterograde labeling method is used to trace the path of efferent axons with PHA-L, a lectin from the kidney bean.[15]

A lectin (BanLec) from bananas inhibits HIV-1 in vitro.[16] Achylectins, isolated from Tachypleus tridentatus, show specific agglutinating activity against human A-type erythrocytes. Anti-B agglutinins such as anti-BCJ and anti-BLD separated from Charybdis japonica and Lymantria dispar, respectively, are of value both in routine blood grouping and research.[17]

Use in studying carbohydrate recognition by proteins

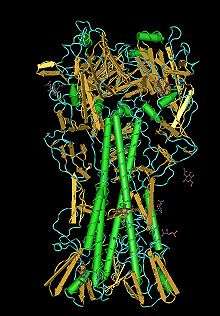

Lectins from legume plants, such as PHA or concanavalin A, have been used widely as model systems to understand the molecular basis of how proteins recognize carbohydrates, because they are relatively easy to obtain and have a wide variety of sugar specificities. The many crystal structures of legume lectins have led to a detailed insight of the atomic interactions between carbohydrates and proteins.

Use as a biochemical tool

Concanavalin A and other commercially available lectins have been used widely in affinity chromatography for purifying glycoproteins. [18]

In general, proteins may be characterized with respect to glycoforms and carbohydrate structure by means of affinity chromatography, blotting, affinity electrophoresis, and affinity immunoelectrophoreis with lectins as well as in microarrays, as in evanescent-field fluorescence-assisted lectin microarray.[19]

Use in biochemical warfare

One example of the powerful biological attributes of lectins is the biochemical warfare agent ricin. The protein ricin is isolated from seeds of the castor oil plant and comprises two protein domains. Abrin from the jequirity pea is similar:

- One domain is a lectin that binds cell surface galactosyl residues and enables the protein to enter cells

- The second domain is an N-glycosidase that cleaves nucleobases from ribosomal RNA, resulting in inhibition of protein synthesis and cell death.

Toxicity

Lectins are ubiquitous in nature and many foods contain the proteins. Because some lectins can be harmful if poorly cooked or consumed in great quantities, "lectin-free" fad diets have been proposed, most based on the writing of Steven Gundry. A typical lectin-free diet excludes a range of foods, including most grains, pulses and legumes, as well as eggs, seafood and many staple fruits and vegetables. These foods do not contain harmful levels of lectins when properly cooked, and there is no health benefit to following these diets for most people. A strict lectin-free diet is unbalanced and dangerously low in many nutrients, requiring significant dietary supplementation to maintain health.[20][21]

Lectins are one of many toxic constituents of many raw plants, which are inactivated by proper processing and preparation (e.g., cooking with heat, fermentation).[22] For example, raw kidney beans naturally contain toxic levels of lectin (e.g. phytohaemagglutinin).

Effects of exposure

Adverse effects may include nutritional deficiencies, and immune (allergic) reactions.[23]

Hemagglutination

Lectins are considered a major family of protein antinutrients (ANCs), which are specific sugar-binding proteins exhibiting reversible carbohydrate-binding activities.[24] Lectins are similar to antibodies in their ability to agglutinate red blood cells.[25]

Many legume seeds have been proven to contain high lectin activity, termed "hemagglutination."[26] Soybean is the most important grain legume crop in this category. Its seeds contain high activity of soybean lectins (soybean agglutinin or SBA). SBA is able to disrupt small intestinal metabolism and damage small intestinal villi via the ability of lectins to bind with brush border surfaces in the distal part of small intestine.[27]

See also

- Bacillus thuringiensis

- Concanavalin A, Phytohaemagglutinin

- Con A Proteopedia 1bxh, Pokeweed lectin Proteopedia 1uha, Artocarpus lectin Proteopedia 1toq, Pterocarpus lectin Proteopedia 1q8v, Urtica lectin Proteopedia 1en2

- Lectin pathway, Ficolin

- Toxalbumin

References

- ↑ URS Rutishauser and Leo Sachs (May 1, 1975). "Cell-to-Cell Binding Induced by Different Lectins". Journal of Cell Biology. Rockefeller University Press. 65 (2): 247–257. doi:10.1083/jcb.65.2.247. PMC 2109424. PMID 805150.

- ↑ Matthew Brudner, Marshall Karpel, Calli Lear, Li Chen, L. Michael Yantosca, Corinne Scully, Ashish Sarraju, Anna Sokolovska, M. Reza Zariffard, Damon P. Eisen, Bruce A. Mungall, Darrell N. Kotton, Amel Omari, I-Chueh Huang, Michael Farzan, Kazue Takahashi, Lynda Stuart, Gregory L. Stahl, Alan B. Ezekowitz, Gregory T. Spear, Gene G. Olinger, Emmett V. Schmidt, and Ian C. Michelow1 (April 2, 2013). Bradley S. Schneider, ed. "Lectin-Dependent Enhancement of Ebola Virus Infection via Soluble and Transmembrane C-type Lectin Receptors". PLoS ONE. 8 (4 specific e code=e60838): e60838. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860838B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060838. PMC 3614905. PMID 23573288.

- ↑ Chan, Charles KF; Ransom, Ryan C; Longaker, Michael T (13 December 2016). "Lectins bring benefits to bones". eLife. 5. doi:10.7554/eLife.22926. PMC 5154756. PMID 27960074.

- ↑ "THE LECTIN STORY".

- ↑ "Lectin list" (PDF). Interchim. 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1365-2559.1985.tb02790.x

- ↑ Els. J. M. Van Damme, Willy J. Peumans, llArpad Pusztai, Susan Bardocz (March 30, 1998). Handbook of Plant Lectins: Properties and Biomedical Applications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-471-96445-2. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ↑ Maverakis E, Kim K, Shimoda M, Gershwin M, Patel F, Wilken R, Raychaudhuri S, Ruhaak LR, Lebrilla CB (2015). "Glycans in the immune system and The Altered Glycan Theory of Autoimmunity". J Autoimmun. 57 (6): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2014.12.002. PMC 4340844. PMID 25578468.

- ↑ Arasu, Abirami; Kumaresan, Venkatesh; Sathyamoorthi, Akila; Palanisamy, Rajesh; Prabha, Nagaram; Bhatt, Prasanth; Roy, Arpita; Thirumalai, Muthukumaresan Kuppusamy; Gnanam, Annie J.; Pasupuleti, Mukesh; Marimuthu, Kasi; Arockiaraj, Jesu (2013). "Fish lily type lectin-1 contains β-prism architecture: Immunological characterization". Molecular Immunology. 56 (4): 497–506. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2013.06.020. PMID 23911406.

- ↑ Oldroyd, Giles E.D.; Downie, J. Allan (2008). "Coordinating Nodule Morphogenesis with Rhizobial Infection in Legumes". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 59: 519–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092839. PMID 18444906.

- ↑ Komath SS, Kavitha M, Swamy MJ (March 2006). "Beyond carbohydrate binding: new directions in plant lectin research". Org. Biomol. Chem. 4 (6): 973–88. doi:10.1039/b515446d. PMID 16525538.

- ↑ R. Bartenschlager, S. Sparacio (2007). "Hepatitis C Virus Molecular Clones and Their Replication Capacity in Vivo and in Cell Culture". Virus Research. Elsevier. 127 (2): 195–207. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.022. PMID 17428568.

- ↑ Soto, GE; Hultgren, SJ (1999). "Bacterial adhesins: common themes and variations in architecture and assembly". J Bacteriol. 181 (4): 1059–1071. PMID 9973330.

- ↑ Sharon, N.; Lis, H (2004). "History of lectins: From hemagglutinins to biological recognition molecules". Glycobiology. 14 (11): 53R–62R. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwh122. PMID 15229195.

- ↑ Carlson, Neil R. (2007). Physiology of behavior. Boston: Pearson Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 0-205-46724-5.

- ↑ Swanson, M. D.; Winter, H. C.; Goldstein, I. J.; Markovitz, D. M. (2010). "A Lectin Isolated from Bananas is a Potent Inhibitor of HIV Replication". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (12): 8646–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.034926. PMC 2838287. PMID 20080975.

- ↑ Viswambari Devi, R.; Basilrose, M. R.; Mercy, P. D. (2010). "Prospect for lectins in arthropods". Italian Journal of Zoology. 77 (3): 254–260. doi:10.1080/11250003.2010.492794.

- ↑ "Immobilized Lectin". legacy.gelifesciences.com.

- ↑ Glyco Station, Lec Chip, Glycan profiling technology Archived 2010-02-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Rosenbloom, Cara (7 July 2017). "Going 'lectin-free' is the latest pseudoscience diet fad". Washington Post. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Warner, Anthony (27 July 2017). "Lectin-free is the new food fad that deserves to be skewered". New Scientist. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Taylor, Steve (2008). "40: Food Toxicology (Lectins: Cell-Agglutinating and Sugar-Specific Proteins)". In Metcalfe, Dean; Sampson, Hugh; Simon, Ronald. Food Allergy: Adverse Reactions to Foods and Food Additives (4th ed.). pp. 498–507.

- ↑ Cordain, Loren; Toohey, L.; Smith, M. J.; Hickey, M. S. (2007). "Modulation of immune function by dietary lectins in rheumatoid arthritis". British Journal of Nutrition. 83 (3): 207–17. doi:10.1017/S0007114500000271. PMID 10884708.

- ↑ Goldstein, Erwin; Hayes, Colleen (1978). "The Lectins: Carbohydrate-Binding Proteins of Plants and Animals". Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry. 35: 127–340. doi:10.1016/S0065-2318(08)60220-6. ISBN 9780120072354. PMID 356549.

- ↑ Sharon, Nathan; Lis, Halina (1972). "Lectins: Cell-Agglutinating and Sugar-Specific Proteins". Science. 177 (4053): 949–959. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..949S. doi:10.1126/science.177.4053.949.

- ↑ Ellen, R.P.; Fillery, E.D.; Chan, K.H.; Grove, D.A. (1980). "Sialidase-Enhanced Lectin-Like Mechanism for Actinomyces viscosus and Actinomyces naeslundii Hemagglutination". Infection and Immunity. 27 (2): 335–343.

- ↑ Hajos, Gyongyi; Gelencser, Eva (1995). "Biological Effects and Survival of Trypsin Inhibitors and the Agglutinin from Soybean in the Small Intestine of the Rat". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 43 (1): 165–170. doi:10.1021/jf00049a030.

Further reading

- Halina Lis; Sharon, Nathan (2007). Lectins (Second ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 1-4020-6605-8.

- Ni Y, Tizard I (1996). "Lectin-carbohydrate interaction in the immune system". Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 55 (1–3): 205–23. doi:10.1016/S0165-2427(96)05718-2. PMID 9014318.

External links

- Major Lectins & Conjugated Lectins from different natural sources

- Functional Glycomics Gateway, a collaboration between the Consortium for Functional Glycomics and Nature Publishing Group

- Introduction by Jun Hirabayashi

- Proteopedia shows more than 800 three-dimensional molecular models of lectins, fragments of lectins and complexes with carbohydrates

- EY Laboratories, Inc., Lectin and Lectin Conjugates manufacturer

- Recombinant Protein Purification Handbook

- Immobilized lectins, chromatography media

- Medicago AB, Lectin and Lectin Conjugates manufacturer