Muratorian fragment

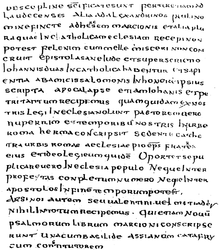

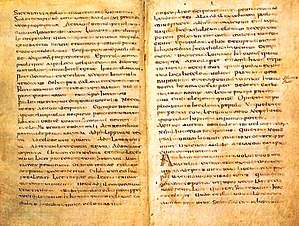

The Muratorian fragment, also known as the Muratorian Canon[1](18:02) or Canon Muratori, is a copy of perhaps the oldest known list of most of the books of the New Testament. The fragment, consisting of 85 lines, is a 7th-century Latin manuscript bound in a 7th or 8th century codex from the library of Columbanus's monastery at Bobbio Abbey; it contains features suggesting it is a translation from a Greek original written about 170 or as late as the 4th century. Both the degraded condition of the manuscript and the poor Latin in which it was written have made it difficult to translate. The beginning of the fragment is missing, and it ends abruptly. The fragment consists of all that remains of a section of a list of all the works that were accepted as canonical by the churches known to its original compiler. It was discovered in the Ambrosian Library in Milan by Father Ludovico Antonio Muratori (1672–1750), the most famous Italian historian of his generation, and published in 1740.[2]

The definitive formation of the New Testament canon did not occur until 367, when bishop Athanasius of Alexandria in his annual Easter letter composed the list that is still recognised today as the canon of 27 books. However, it would take several more centuries of debates until agreement on Athanasius' canon had been reached within all of Christendom.[1](7:30)

Characteristics

The text of the list itself is traditionally dated to about 170 because its author refers to Pius I, bishop of Rome (140—155), as recent:

But Hermas wrote The Shepherd "most recently in our time", in the city of Rome, while bishop Pius, his brother, was occupying the chair of the church of the city of Rome. And therefore it ought indeed to be read; but it cannot be read publicly to the people in church either among the Prophets, whose number is complete, or among the Apostles, for it is after their time.

The document contains a list of the books of the New Testament, a similar list concerning the Old Testament having apparently preceded it. It is in barbarous Latin which has probably been translated from original Greek—the language prevailing in Christian Rome until c. 200.[3]

A few scholars[4] have also dated it as late as the 4th century, but their arguments have not won widespread acceptance in the scholarly community. For more detail, see the article in the Anchor Bible Dictionary. Bruce Metzger has advocated the traditional dating,[5] as has Charles E. Hill.[6]

The unidentified author accepts four Gospels, the last two of which are Luke and John, but the names of the first two at the beginning of the list are missing. Scholars find it highly likely that the missing two gospels are Matthew and Mark, although this remains uncertain.[1](19:44) Also accepted by the author are the "Acts of all Apostles" and 13 of the Pauline Epistles (the Epistle to the Hebrews is not mentioned in the fragment). The author considers spurious the letters claiming to have Paul as author that are ostensibly addressed to the Laodiceans and to the Alexandrians. Of these he says they are "forged in Paul's name to [further] the heresy of Marcion."

Of the General epistles, the author accepts the Epistle of Jude and says that two epistles "bearing the name of John are counted in the catholic church"; 1 and 2 Peter and James are not mentioned in the fragment. It is clear that the author assumed that the author of the Gospel of John was the same as the author of the First Epistle of John, for in the middle of discussing the Gospel of John he says "what marvel then is it that John brings forward these several things so constantly in his epistles also, saying in his own person, "What we have seen with our eyes and heard with our ears, and our hands have handled that have we written," (1 John 1:1) which is a quotation from the First Epistle of John. It is not clear whether the other epistle in question is 2 John or 3 John. Another indication that the author identified the Gospel writer John with two epistles bearing John's name is that when he specifically addresses the epistles of John, he writes, "the Epistle of Jude indeed, and the two belonging to the above mentioned John." In other words, he thinks that these letters were written by the John whom he has already discussed, namely John the gospel writer. He gives no indication that he considers the John of the Apocalypse to be a different John from the author of the Gospel of John.

Indeed, by calling the author of the Apocalypse of John the "predecessor" of Paul, who, he assumes, wrote to seven churches (Rev 2–3) before Paul wrote to seven churches [lines 48–50],[7] he most likely has in mind the gospel writer, since he assumes that the writer of the Gospel of John was an eyewitness disciple who knew Jesus, and thus preceded Paul who joined the church only a few years after Jesus' death.

In addition to receiving the Apocalypse of John into the church canon, the author remarks that they also receive the Apocalypse of Peter, although "some of us will not allow the latter to be read in church"[line 72].[7] However, it is not certain whether this refers to the Greek Apocalypse of Peter or the quite different Coptic Apocalypse of Peter, the latter of which, unlike the former, was Gnostic. The author also includes the Book of Wisdom, "written by the friends of Solomon in his honour"[line 70][7] in the canon.

Comparison

| Book | Muratorian Canon | Present canon[8] |

|---|---|---|

| Gospel of Matthew | Probably[9] | Yes |

| Gospel of Mark | Probably[9] | Yes |

| Gospel of Luke | Yes | Yes |

| Gospel of John | Yes | Yes |

| Acts of the Apostles | Yes | Yes |

| Romans | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Corinthians | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Corinthians | Yes | Yes |

| Galatians | Yes | Yes |

| Ephesians | Yes | Yes |

| Philippians | Yes | Yes |

| Colossians | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Thessalonians | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Thessalonians | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Timothy | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Timothy | Yes | Yes |

| Titus | Yes | Yes |

| Philemon | Yes | Yes |

| Hebrews | No | Yes[10] |

| James | No | Yes[10] |

| 1 Peter | No | Yes |

| 2 Peter | No | Yes |

| 1 John | Probably[11] | Yes |

| 2 John | Maybe[11] | Yes |

| 3 John | Maybe[11] | Yes |

| Jude | Yes | Yes[10] |

| Apocalypse of John | Yes | Yes[10] |

| Apocalypse of Peter | Yes | No |

| Wisdom of Solomon | Yes | No |

References

- 1 2 3 Bart D. Ehrman (2002). "21: Formation Of The New Testament Canon". Lost Christianities. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ↑ Muratori, Antiquitates Italicae Medii Aevii (Milan 1740), vol. III, pp 809–80. Located within Dissertatio XLIII (cols. 807-80), entitled 'De Literarum Statu., neglectu, & cultura in Italia post Barbaros in eam invectos usque ad Anum Christii Millesimum Centesimum', at cols. 851-56.

- ↑ "MURATORI - Online Information article about MURATORI". encyclopedia.jrank.org. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Hahneman, Geoffrey Mark. The Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon. (Oxford: Clarendon) 1992. Sundberg, Albert C., Jr. "Canon Muratori: A Fourth Century List" in Harvard Theological Review 66 (1973): 1–41.

- ↑ Metzger, The Canon Of The New Testament: Its Origin, Significance & Development (1997, Clarendon Press, Oxford),

- ↑ ""The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon," Westminster Theological Journal 57:2 (Fall 1995)" (PDF). earlychurch.org.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "The Muratorian Fragment". www.bible-researcher.com. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ The Assyrian Church of the East does not recognise the following books: 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Epistle of Jude, Apocalypse of John. Moreover, it rejects certain verses of books as non-canonical: Matthew 27:35(b), Luke 22:17-18, John 7:53, 8:1-11, Acts 8:37, 15:34 and 28:29, and 1 John 5:7.

- 1 2 The beginning of the Muratorian Canon is lost; the fragment that has survived, starts by naming Luke the third gospel and John the fourth. Historians therefore assume that the first two gospels would have been Matthew and Mark, although this remains uncertain.

- 1 2 3 4 Martin Luther doubted the canonicity of Hebrews, James, Jude and the Apocalypse of John. He showed this by the way in which he ordered them. However, he did incorporate the books in his canon, and all Lutheran communities have done so since.

- 1 2 3 The Muratorian fragment mentions two letters by John, but gives little clues as to which ones. Therefore, it is not known which of the three was excluded that would later be considered canonical. Bruce Metzger concluded that the Muratorian fragment cites 1 John 1:1-3 when it says: "What marvel is it then, if John so consistently mentions these particular points also in his Epistles, saying about himself, 'What we have seen with our eyes and heard with our ears and our hands have handled, these things we have written to you?'". Bruce Metzger (translator). "The Muratorian fragment". EarlyChristianWritings.com. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

Other sources

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

According to The Catholic Encyclopaedia, lines of the Muratorian fragment are preserved in "some other manuscripts", including codices of Paul's Epistles at the abbey of Monte Cassino.

Further reading

- Metzger, Bruce M., 1987. The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. (Clarendon Press. Oxford) ISBN 0-19-826954-4

- Jonathan J. Armstrong, "Victorinus of Pettau as the Author of the Canon Muratori," Vigiliae Christianae, 62,1 (2008), pp 1–34.

- Anchor Bible Dictionary

- Bruce, F.F. The Canon of Scripture. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1988.

- Verheyden, J., "The Canon Muratori: A Matter of dispute," Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium (2003), The Biblical Canons, ed. by J.-M. Auwers & H. J. De Jonge, p. 487–556.

External links

- Text of the Muratorian fragment.

- "The development of the canon of the New Testament": The Muratorian Canon

- Henry Wace, A Dictionary of Christian biography: Muratorian fragment

- Earlychristianwritings.com: Original and amended Latin and English translation of the Muratorian fragment.

- Muratorian Fragment in the Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible

- C. E. Hill, “The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon,” Westminster Theological Journal 57:2 (Fall 1995): 437–452(PDF)

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Muratori

- More information at Earlier Latin Manuscripts