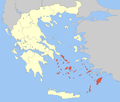

Milos

| Milos Μήλος | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

From top: | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Coordinates: 36°41′N 24°25′E / 36.683°N 24.417°ECoordinates: 36°41′N 24°25′E / 36.683°N 24.417°E | |||||

| Country |

| ||||

| Administrative region |

| ||||

| Regional unit | Milos | ||||

| Capital | Plaka | ||||

| Highest elevation | 748 m (2,454 ft) | ||||

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) | ||||

| Population (2011) | |||||

| • Total | 4,977 | ||||

| Demonym(s) | Melian | ||||

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) | ||||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) | ||||

| Postal code | 848 00, 848 01 | ||||

| Telephone | 2287 | ||||

| Website | www.milos.gr | ||||

Milos or Melos (/ˈmɛlɒs,

The island is famous for the statue of Aphrodite (the "Venus de Milo", now in the Louvre), and also for statues of the Greek god Asclepius (now in the British Museum[1]), the Poseidon and an archaic Apollo in Athens. Milos is a popular tourist destination during the summer. The Municipality of Milos also includes the uninhabited offshore islands of Antimilos and Akradies. The combined land area is 160.147 square kilometres (61.833 sq mi)[2] and the 2011 census population was 4,977 inhabitants.

History

Obsidian (a glass-like volcanic rock) from Milos was a commodity as early as 15,000 years ago.[3] Natural glass from Milos was transported over long distances and used for razor-sharp "stone tools" well before farming began and later: "There is no early farming village in the Near East that doesn't get obsidian".[4] The mining of obsidian did not lead to the development of permanent habitation or manufacturing on the island. Instead, those in search of obsidian arrived by boat, beaching it in a suitable cove and cutting pieces of the volcanic glass from the quarries.[5]

The position of Milos, between mainland Greece and Crete, and its possession of obsidian, made it an important centre of early Aegean civilisation. Milos lost its arms-making importance when bronze became the preferred material for the manufacture of weapons.[6]

The Bronze Age

The first settlement at Phylakopi (Greek Φυλακωπή) arose in the Bronze Age, flourishing as the extraction of obsidian was in the decline. The first settlers were tuna fishermen.[5] Lying on the north-east coast, 1896 excavations by the British School at Athens revealed a town wall and a Minoan-inspired structure, dubbed the Pillar room, which contained fragments of vivid wall paintings. The famous fresco of the flying fish[7] was found in the ruins of the Pillar room and was executed with delicate colouring and graphic observation of nature in the graceful movement of a fish. Stylistic similarities to Minoan frescoes are suggested, and it could perhaps have been the work of a Cretan artist.[8] Part of the site has been washed away by the sea.

The antiquities found at the site covered three major periods, from the Early Cycladic period to the Mycenaean period. At the site much pottery was excavated, with several changing styles and influences over the site's long occupation. In the early occupation of the site, there are many similarities and imports from other Cycladic islands and the settlement was very small. During the Middle Bronze Age however, the site expanded significantly and the expansion of Minoan Crete saw an influx of Minoan pottery into the Cyclades, particularly at Akrotiri on Thera, though much found its way to Phylakopi. The quantities found at the Cycladic sites have been taken to suggest a Minoan control over the region, though it could also be the consumptive nature of the islanders adopting Cretan fashions. There is more than just pottery at Phylakopi however, the eruption of the Thera volcano saw a reduction in Minoan presence in the Cyclades and it is at this time that Mycenaean involvement on the islands increases. At Phylakopi (and unknown in the rest of the Cyclades) a megaron structure, which is typically associated with the Mycenaean palaces, such as those at Tiryns, Pylos and Mycenae has been discovered. This has been taken to suggest that the Mycenaeans conquered the settlement and installed a seat of power for a governor. The evidence is not clear, though again it could be a legacy of the islanders adopting foreign elements into their culture. Particularly unexpected was the discovery in the 1970s of a shrine at the site, which contained many examples of Aegean figurines, including the famous "Lady of Phylakopi". The shrine is unprecedented in the Bronze Age Cyclades and has provided a valuable insight into the beliefs and rituals of the inhabitants of Phylakopi. The site was eventually abandoned and was never reoccupied.

Dorian settlement

The first Dorian settlement on Melos was established no earlier than the 1st millennium BC. Dorians are the ethnic group to which the Spartans belonged, but the Dorian settlers of Melos made themselves independent. They eventually established a city whose site lies on the eastern shore of the bay, just south-west of the present-day community of Trypiti.

From the 6th century BC up to the siege of 416 BC, Melos issued its own coinage, struck according to the Milesian weight standard: the base coin was the stater which weighed just over 14 grams.[11][12][13] Melos was the only island in the Aegean Sea to use this standard.[14] Most coins bore the image of an apple, which is a pun because the ancient Greek word for "apple" (mêlon) sounded similar to the name of the island.[15] The coins also often bore the name of its people: ΜΑΛΙΟΝ (Malion) or some abbreviation thereof.[16]

By the 6th century BC, the Melians had also learned to write, and they used an archaic variant of the ancient Greek script that exhibited Cretan and Theraic influences. It was discarded after the siege of 416 BC.[17]

| Α | Β | Γ | Δ | Ε | Ϝ | Ζ | Η | Η | Θ | Ι | Κ | Λ | Μ | Ν | Ξ | Ο | Π | Ϻ | Ϙ | Ρ | Σ | Τ | Υ | Φ | Χ | Ψ | Ω | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laconia (Sparta) |

– | – | (φσ) | – | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Attica (Athens) |

– | (χσ) | – | (φσ) | – | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melos | – | (κϻ) | – | (πh) | (κh) | (πϻ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

From at least as early as 470 BC and ending with the siege of 416 BC, the Melians exported terracotta reliefs, which were typically use as door or chest ornaments and depicted scenes from mythology.

During the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, the Melians refused to submit to Persia and contributed two warships to the Greek war effort, which were used at the Battle of Salamis.[18] After the battle, the Melians returned to their traditional isolationism.[19]

A Melian stater from the 5th century.

A Melian stater from the 5th century. Melian terracotta relief depicting Triton and Theseus.

Melian terracotta relief depicting Triton and Theseus.

Siege of 416 BC

During the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) between Athens and Sparta, the Melians made some small donations to the Spartan war effort[20][21] but remained largely neutral despite sharing the Spartans' Dorian ethnicity. In 426 BC, the Athenians raided the Melian countryside, and the following year demanded tribute[22], but Melos refused. In the summer of 416 BC, Athens invaded again with 3,400 men, and demanded that Melos ally with them against Sparta, or be destroyed. The Melians rejected this, so the Athenian army laid siege to the city and eventually captured it in the winter of 416 or 415 BC. After the city's fall, the Athenians executed all the adult men[23], and sold the women and children into slavery. They then settled 500 of their own colonists on the island.[24] In 405 BC, with Athens losing the war, the Spartan general Lysander expelled the Athenian settlers from Melos and repatriated the survivors of the siege.[25][26] Sparta annexed Melos and installed a military governor (a harmost).[27]

The Greek historian Thucydides dramatized the failed negotiations between the Athenians and the Melians in his famous Melian Dialogue. This piece has since become a classic case study in political realism, an argument that states pursue their own selfish interests over moral concerns.

The tribulations of its population and the loss of its independence meant that the cultural distinctiveness of Melos faded away as it was absorbed into mainstream Greek culture.[28] Their coinage switched to the Rhodian standard[29] (tetradrachms weighing 15.3 g[30]) and ceased bearing the word ΜΑΛΙΟΝ. The production of its terracotta reliefs also ceased.

The Hellenistic period

In 338 BC, Philip II of Macedon defeated the Greeks at the Battle of Chaeroneia and became the overlord of Greece and the Cyclades. During this time, Melos and the nearby island Kimolos disputed each other over the ownership of the islands of Polyaigos, Heterea, and Libea (the last two are probably today's uninhabited islands of Agios Efstathios and Agios Georgios). In the past, this dispute would have been settled by war, but the two communities took their dispute to Argos on the Greek mainland. The Argives decided the islands belonged to Kimolos.[31]

The Roman and Byzantine period

In 197 BC, the Romans forced Philip V to withdraw from Greece, and Melos subsequently came under Roman influence.

During the early 9th century CE the Cyclades were harassed by Arab raiders, though how Milos fared at this time is unclear. Milos was mentioned in a Byzantine chrysobull of 1198, which shows it was still important to the Byzantines.[32]

Medieval period

In the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade (1204), the Venetian Marco Sanudo seized control of Milos and a number of other islands in the Cyclades. Sanudo declared himself the Duke of Naxos, after the island where he established his capital. Sanudo did not make his duchy a vassal of Venice, but instead declared loyalty to the Latin Emperor.[33] Sanudo's dynasty lasted nine generations, then was succeeded by the Crispos. Both families were Catholic. The majority of the population was (and still is) Greek Orthodox.

Up to this point, the population of Melos was overwhelmingly Greek Orthodox Christian, just like the rest of the archipelago. When the Venetians conquered the archipelago, they brought Catholicism with them. The first Catholic bishop of Milos was appointed in 1253.[34]

Ottoman period

In 1566 the Venetians handed over the Duchy of Naxos to the Ottoman Empire, and its last Catholic duke fled to Venice. The Ottoman sultan Selim II appointed a Portuguese Jew named Joseph Nasi as its duke. Upon Nasi's death in 1579, the Ottomans formally annexed the territory.[35]

In the early 18th century, the population surpassed 6,000[36] and was almost entirely Greek and Christian. It was ruled by Turkish judge or kadi, and a Turkish governor or voivode. The voivode was responsible for collecting taxes and enforcing the decisions of the kadi. The day-to-day affairs of the island were managed by three elected magistrates (epitropi), although any of their decisions could be appealed to the kadi. The island had two bishops: one Greek Orthodox and one Latin Catholic. The Greek bishop was wealthier than his Latin counterpart, as he had a larger revenue base. Although the islanders enjoyed a great degree of autonomy, they chafed under the heavy taxation of their Ottoman overlords.[37][38]

In 1771 the island was occupied by the Russian Empire for three years, then retaken by the Ottomans.

In the late 18th century, the population declined considerably for uncertain reasons.[39] By 1798, it had fallen below 500 people.[40] Visitors reported that up to two thirds of the buildings had fallen into ruin. It began growing again in the early 19th century, reaching 5,000 people by 1821.[41] Reliable figures are hard to find as the Ottoman Empire never performed a census before 1881.

Modern period

Melos was one of the first islands to join the Greek War of Independence of 1821.

During the 19th century, Melos was a major rendezvous point for American and British ships fighting Muslim pirates in the Mediterranean.

The population peaked in 1928 at 6,562 people.[42] In 2011 it was 4,977.

Geography

Milos is the southwesternmost island in the Cyclades, 120 kilometres (75 miles) due east from the coast of Laconia. From east to west it measures about 23 km (14 mi), from north to south 13 km (8.1 mi), and its area is estimated at 151 square kilometres (58 sq mi). The greater portion is rugged and hilly, culminating in Mount Profitis Elias 748 metres (2,454 feet) in the west. Like the rest of the cluster, the island is of volcanic origin, with tuff, trachyte and obsidian among its ordinary rocks. The natural harbour is the hollow of the principal crater, which, with a depth diminishing from 70 to 30 fathoms (130–55 m), strikes in from the northwest so as to separate the island into two fairly equal portions (see photo), with an isthmus not more than 18 km (11 mi) broad. In one of the caves on the south coast, the heat from the volcano is still great, and on the eastern shore of the harbour, there are hot sulfurous springs.

Antimelos or Antimilos, 13 miles (21 km) north-west of Milos, is an uninhabited mass of trachyte, often called Erimomilos (Desert Milos). Kimolos, or Argentiera, 1.6 km (0.99 mi) to the north-east, was famous in antiquity for its figs and fuller's earth, and contained a considerable city, the remains of which cover the cliff of St. Andrew's. Polyaigos (also called Polinos, Polybos or Polivo — alternative spelling Polyaegos) lies 2 km (1 mi) south-east of Kimolos. It was the subject of dispute between the Milians and Kimolians. It is now uninhabited.

The harbour town is Adamantas; from this there is an ascent to the plateau above the harbour, on which are situated Plaka, the chief town, and Kastro, rising on a hill above it, and other villages. The ancient town of Milos was nearer to the entrance of the harbour than Adamas, and occupied the slope between the village of Trypiti and the landing-place at Klima. Here is a theatre of Roman date and some remains of town walls and other buildings, one with a fine mosaic excavated by the British school at Athens in 1896. Numerous fine works of art have been found on this site, notably the Aphrodite in Paris, the Asclepius in London, and the Poseidon and the archaic Apollo in Athens. Other villages include Triovasalos, Peran Triovasalos, Pollonia and Zefyria (Kampos).

Climate

Milos has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa) with mild, rainy winters and warm to hot dry summers.[43]

| Climate data for Milos | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.6 (70.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

35.4 (95.7) |

40.0 (104) |

41.0 (105.8) |

38.4 (101.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

27.8 (82) |

23.4 (74.1) |

41.0 (105.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.8 (73) |

27.1 (80.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.5 (50.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.0 (77) |

24.6 (76.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

16.1 (61) |

13.1 (55.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.0 (32) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.0 (50) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

2.8 (37) |

0.0 (32) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 74.7 (2.941) |

50.6 (1.992) |

47.2 (1.858) |

20.5 (0.807) |

13.1 (0.516) |

3.3 (0.13) |

0.3 (0.012) |

1.4 (0.055) |

5.8 (0.228) |

42.9 (1.689) |

60.7 (2.39) |

90.3 (3.555) |

410.8 (16.173) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.8 | 7.3 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 9.0 | 46.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.3 | 72.5 | 72.0 | 67.0 | 63.5 | 58.8 | 60.1 | 63.4 | 66.8 | 71.3 | 73.9 | 73.7 | 68.0 |

| Source: NOAA[44] | |||||||||||||

Natural resources

Bentonite, perlite, pozzolana and small quantities of kaolin are actively collected via strip mine or open-pit mine techniques in Milos and sold all over the world. In the past, baryte, sulfur, millstones and gypsum were also mined; in fact, Pliny notes that Milos was the most abundant source of sulfur in the ancient world.[45] In ancient times the alum of Milos was reckoned next to that of Egypt (Pliny xxxv. 15 [52]). The Melian earth was employed as a pigment by ancient artists. Milos was a source of obsidian during the Neolithic ages for the Aegean and Mediterranean. Orange, olive, cypress, tamarisk, juniper (Juniperus oxycedrus) and arbutus trees grow throughout the island, which, however, is too dry to have any profusion of vegetation. Vines, cotton and barley are the main crops.

Beaches

There are only 70 beaches on Milos Island. Hivadolimni Beach is the longest at about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi). The rest of the beaches are starting from (North): Sarakiniko Beach, Papafragas, Kapros, Pachena, Alogomantra, Konstantinos, Mitakas, Mantrakia, Firopotamos, Nerodafni, Lakida, Plathiena, Fourkovouni, Areti, Pollonia, Gourado and Filakopi. (South): Firiplaka, Paliochori, Provatas, Tsigrado, Agia Kyriaki, Psaravolada, Kleftiko, Gerontas, Gerakas, Agios Sostis, Mouchlioti, Katergo, Spathi, Firligos, Pialothiafes, Kalamos, Krotiraki, Psathi, Svoronou and Sakelari. (West): Agios Ioannis, Cave of Sikia, Agathia, Triades and Ammoudaraki. (East): Voudia, Thalassa, Paliorema, Tria Pagidia and Thiafes. (In the Bay Area): Hivadolimni, Lagada, Papikinou, Fatourena, Klima, Skinopi and Patrikia. The North and South and bay beaches are tourist attractions. The east beaches are very quiet, and those to the west are also quiet beaches.

Demographics

Historical population

| Year | Island population |

|---|---|

| 1798 | 500[40] |

| 1812 | 2,300[46] |

| 1821 | 5,000[41] |

| 1907 | 5,393[47] |

| 1991 | 4,380 |

| 2001 | 4,771 |

| 2011 | 4,977 |

People

- Diagoras (5th century BC), philosopher

- Melanippides (5th century BC), poet

- Antonio Millo (active 1557–1590), captain and cartographer

- Antonio Vassilacchi (1556–1629), painter

Sister island

Gallery

- Antonio Vassilacchi, painter born on Milos in 1556[48]

The tallest peak of Milos (2,440 feet high)

The tallest peak of Milos (2,440 feet high) Thalassitra church at Plaka, Milos

Thalassitra church at Plaka, Milos White volcanic tephra at Sarakiniko beach

White volcanic tephra at Sarakiniko beach Inscription on a tomb in the catacombs of Milos

Inscription on a tomb in the catacombs of Milos.jpg) The lair of the Saracen pirates in Sarakiniko beach

The lair of the Saracen pirates in Sarakiniko beach.jpg) Inside the lair of the pirates

Inside the lair of the pirates Gerakas Beach

Gerakas Beach The salty slide of Gerakas Beach

The salty slide of Gerakas Beach- Southeast Milos showing the beaches of Agia Kyriaki and Paliochori in August 2014

See also

References

- ↑ British Museum Collection

- ↑ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- ↑ N. Laskaris, A. Sampson, F. Mavridis, I. Liritzis, (September 2011) "Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene seafaring in the Aegean: new obsidian hydration dates with the SIMS-SS method" Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 38, Issue 9, pp.2475–2479

- ↑ C. Renferew

- 1 2 David Abulafia (2011). The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-196999-2.

- ↑ Chalk and Jonassohn, 65

- ↑ Flying fish Archived 2015-10-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ CAH pg. 448

- ↑ Based on a map by Brian Sparkes, published in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982).

- ↑ Based on a map by Brian Sparkes, published in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982).

- ↑ Brain Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p 230: "Melian coins of the late sixth and fifth centuries are of silver [...] and based on the Milesian weight standard."

- ↑ Gardner (1918): "Already, in the sixth century, Melos struck coins on a different standard from that of most of the other islands of the Aegean, the stater weighing about 224 grains (grm. 14.50). Certain coins of the Santorin find (p. 122) are not of Aeginetan but of this Phoenician weight."

- ↑ According to the website of Robert J. O'Hara (http://rjohara.net/coins/history/), a Lydo-Milesian stater weighed 14.10 grams.

- ↑ Brain Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p 47

- ↑ Hill (1899), p. 176

- ↑ Brain Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p 230

- ↑ Brain Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982)

- ↑ Herodotus. The Histories, 46-48: "The Seriphians, Siphnians, and Melians also took part, since they were the only islanders who had not given earth and water to the barbarian. [...] All of these came to the war providing triremes, except the Melians and Siphnians and Seriphians, who brought fifty-oared boats. The Melians (who are of Lacedaemonian stock) provided two; the Siphnians and Seriphians, who are Ionians from Athens, one each. The total number of ships, besides the fifty-oared boats, was three hundred and seventy-eight."

- ↑ Brain Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p 49

- ↑ Geoffrey Ernest Maurice de Ste Croix (1954). "The Character of the Athenian Empire". An essay originally published in Historia 3, republished in Low (2008): "Epigraphic evidence allows us to go further still: it puts the original Athenian attack on Melos in quite a different light. The inscription found near Sparta [...] records two separate donations by Melos to the Spartan war-funds, one of twenty Aeginetan minae [...] The other figure has perished. The donors are described, it will be noticed, as toi Malioi, 'the Melians'. [...] This shows that the Melian subscription was an official one. [...] there is good reason to think these gifts to Sparta were made in the spring of 427."

- ↑ The evidence is an inscription (IG V 1, 1) which reads: "The Melians gave to the Lacedaimonians twenty mnas of silver." See Loomis (1992), p 13

- ↑ Brian Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p. 49

- ↑ Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War, 116

The key word in the account by Thucydides is hebôntas (ἡβῶντας), which generally describes people who have passed puberty and in this context refers to the men as Thucydides described a different fate for the women and children. Some translators such as Rex Warner translated this as "men of military age". Another possible translation is "men in their prime". Thucydides made no specific mention of what happened to the elderly males. - ↑ Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War, 5.84-116

- ↑ Xenophon. Hellenica, 2.2.9: "Meantime Lysander, upon reaching Aegina, restored the state to the Aeginetans, gathering together as many of them as he could, and he did the same thing for the Melians also and for all the others who had been deprived of their native states."

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Lysander, 14.3: "But there were other measures of Lysander upon which all the Greeks looked with pleasure, when, for instance, the Aeginetans, after a long time, received back their own city, and when the Melians and Scionaeans were restored to their homes by him, after the Athenians had been driven out and had delivered back the cities."

- ↑ Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p. 51

- ↑ Brian Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982)

- ↑ Brian Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p 231

- ↑ http://rjohara.net/coins/history/#weights

- ↑ Brain Sparkes, in Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p 50

- ↑ Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p. 58

- ↑ Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p. 58-69

- ↑ GCatholic.org - Diocese of Milos

- ↑ http://www.greeka.com/cyclades/milos/milos-history.htm

- ↑ Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982)

- ↑ Tournefort (1717), p. 180-181

- ↑ Thompson (1752), vol 1, p. 291-300

- ↑ Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p. 69

- 1 2 Olivier (1801), p. 156

- 1 2 Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p. 148

- ↑ Renfrew & Wagstaff (1982), p. 70

- ↑ Kottek, M.; J. Grieser; C. Beck; B. Rudolf; F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Milos Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Sulfur. Encyclopedia of Earth, eds. A.Jorgensen and C.J.Cleveland, National Council for Science and the environment, Washington DC Archived 2012-10-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Turner (1820), p. 32

- ↑ 1907 Greek census (1909), statistics.gr, page 411 (Δήμος Μήλου/ Milos Municipality 4.864 + Δήμος Αδάμαντος / Adamas Municipality 529 = 5.393)

- ↑ Gould, John (1838). Biographical dictionary of painters, sculptors, engravers, and architects, from the earliest ages to the present time: interspersed with original anecdotes, Volume 2. Greenland. p. 577. OCLC 261336841.

VASSILACCHI, called L'ALI- ENSE (Antonio), a Greek historical painter, born at Milo, a Greek island in the Venetian territory, in 1556, and died in 1629

Sources

- Hill, G. F. (1899). A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins. Macmillan and Co., Limited.

- Loomis, William T. (1992). The Spartan War Fund: IG V 1, 1 and a New Fragment. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-06147-6.

- Renfrew, Colin; Wagstaff, Malcolm, eds. (1982). An Island Polity: The Archaeology of Exploitation in Melos. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23785-8.

- Thucydides (c. 400 BC). History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Richard Crawley (1914).

- David Abulafia (2011). The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-196999-2.

- Tournefort, Joseph Pitton de (1717). Relation d'un Voyage du Levant [An Account of a Voyage into the Levant] (in French).

- Thompson, Charles (1752). The Travels of the Late Charles Thompson, Esq. 1.

- Turner, William (1820). Journal of a Tour in the Levant, Vol. 1. John Murray, Albermarle-Street.

- Olivier, Guillaume Antoine (1801). Travels in the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Persia. Paris H. Agasse.

Sources

- I.F. Stone, 1988, The trial of Socrates, Anthos.

- Cambridge Ancient History, Vol.II, 1924, New York, MacMillan

- Colin Renfrew and Malcolm Wagstaff (editors), 1982, An Island Polity, the Archaeology of Exploitation in Melos, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Colin Renfrew (editor), 1985, The Archaeology of Cult, the Sanctuary at Phylakopi, London, British School at Athens and Thames & Hudson.

- Leycester, "The Volcanic Group of Milo, Anti-Milo, &c.," in Jour. Roy. Geog. Soc. (1852).

- Tournefort, Voyage.

- William Martin Leake, Northern Greece, iii.

- Anton von Prokesch-Osten, Denkwürdigkeiten, &c.

- Bursian, Geog. von Griechenland, ii.; Journ. Hell. Stud, xvi, xvii, xviii, Excavations at Phylakopi; Inscr. grace, xii. iii. 197 sqq.;

- on coins found in 1909, see Jameson in Rev. Num. 1909; 188 sqq.

- "Mílos". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- Seaman, Michael G., "The Athenian Expedition to Melos in 416 B.C.," Historia 46 (1997) pp. 385–418.

- Chalk, Frank; Jonassohn, Kurt (1990). History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-300-04445-3.

- Bosworth, A.B. (2005). ""Athens and Melos." Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity ed. Dinah L. Shelton". Gale Cengage, enotes.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- Connor, W. Raymond (1984). Thucydides. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 151.

- Thucydides (1954). The Peloponnesian War. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Milos. |

- Official website (in English) (in Greek)