Marxist feminism

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

People

|

|

Marxist feminism is feminism focused on investigating and explaining the ways in which women are oppressed through systems of capitalism and private property.[1] According to Marxist feminists, women's liberation can only be achieved through a radical restructuring of the current capitalist economy, in which, they contend, much of women's labor is uncompensated.[2]

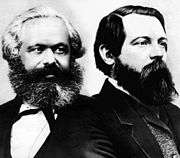

Theoretical background in Marxism

Influential work by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848) in The Communist Manifesto[3] and Marx (1859) in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy laid the foundation for some of the early discourse about the relationship between capitalism and oppression. The theory and method of study developed by Marx (1859), termed historical materialism, recognizes the ways in which economic systems structure society as a whole and influence everyday life and experience.[4] Historical materialism places a heavy emphasis on the role of economic and technological factors in determining the base structure of society. The base structure prescribes a range of systems and institutions aimed to advance the interests of those in power, often facilitated through the exploitation of the working class. Marx (1859) argues that these systems are set by the ruling class in accordance with their need to maintain or increase class conflict in order to remain in power. However, Marx (1859) also acknowledges the potential for organization and collective action by the lower classes with the goal of empowering a new ruling class. As Vladimir Lenin (1917) argues in support of this possibility, the organization of socialist consciousness by a vanguard party is vital to the working class revolutionary process.[5]

In 1884, Engels published The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State.[6] According to Engels (1884), the shift from feudalism to private ownership of land has had a huge effect on the status of women. In a private ownership system, individuals who do not own land or other means of production are in a situation that Engels (1884) compares to enslavement - they must work for the owners of the land in order to be able to live within the system of private ownership. Engels (1884) explains that the transition to this type of system resulted in the creation of separate public and private spheres and assigned access to waged labor disproportionately to men.

Engels (1884) argues that a woman's subordination is not a result of her biological disposition but of social relations, and that men's efforts to achieve their demands for control of women's labor and sexual faculties have gradually become institutionalized in the nuclear family. Through a Marxist historical perspective, Engels (1884) analyzes the widespread social phenomena associated with female sexual morality, such as fixation on virginity and sexual purity, incrimination and violent punishment of women who commit adultery, and demands that women be submissive to their husbands. Ultimately, Engels traces these phenomena to the recent development of exclusive control of private property by the patriarchs of the rising slaveowner class in the ancient mode of production, and the attendant desire to ensure that their inheritance is passed only to their own offspring: chastity and fidelity are rewarded, says Engels (1884), because they guarantee exclusive access to the sexual and reproductive faculty of women possessed by men from the property-owning class.

As such, gender oppression is closely related to class oppression and the relationship between men and women in society is similar to the relations between proletariat and bourgeoisie.[2] On this account women's subordination is a function of class oppression, maintained (like racism) because it serves the interests of capital and the ruling class; it divides men against women, privileges working class men relatively within the capitalist system in order to secure their support; and legitimates the capitalist class's refusal to pay for the domestic labor assigned, unpaid, to women.

Productive and reproductive labour

In the capitalist system, two types of labor exist, a division stressed by Marxist feminists like Margaret Benston and Peggy Morton.[7] The first is productive, in which the labor results in goods or services that have monetary value in the capitalist system and are thus compensated by the producers in the form of a paid wage. The second form of labor is reproductive, which is associated with the private sphere and involves anything that people have to do for themselves that is not for the purposes of receiving a wage (i.e. cleaning, cooking, having children). Both forms of labor are necessary, but people have different access to these forms of labor based on certain aspects of their identity. Women are assigned to the domestic sphere where the labor is reproductive and thus uncompensated and unrecognized in a capitalist system. It is in the best interest of both public and private institutions to exploit the labor of women as an inexpensive method of supporting a work force. For the producers, this means higher profits. For the nuclear family, the power dynamic dictates that domestic work is exclusively to be completed by the woman of the household thus liberating the rest of the members from their own necessary reproductive labor. Marxist feminists argue that the exclusion of women from productive labor leads to male control in both private and public domains.[7][8]

Accomplishments and activism

The militant nature of Marxist feminists and their ability to mobilize to promote social change has enabled them to engage in important activism. Though their controversial advocacy often receives criticism, Marxist feminists challenge capitalism in ways that facilitate new discourse and shed light on the status of women.[8] These women throughout history have used a range of approaches in fighting hegemonic capitalism, which reflect their different views on the optimal method of achieving liberation for women.[2]

Wages for housework

Focusing on exclusion from productive labor as the most important source of female oppression, some Marxist feminists devoted their activism to fighting for the inclusion of domestic work within the waged capitalist economy. The idea of creating compensated reproductive labor was present in the writings of socialists such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1898) who argued that women's oppression stemmed from being forced into the private sphere.[9] Gilman proposed that conditions for women would improve when their work was located, recognized, and valued in the public sphere.[2]

Perhaps the most influential of the efforts to compensate reproductive labor was the International Wages for Housework Campaign, an organization launched in Italy in 1972 by members of the International Feminist Collective. Many of these women, including Selma James,[10] Mariarosa Dalla Costa,[11] Brigitte Galtier, and Silvia Federici[12] published a range of sources to promote their message in academic and public domains. Despite the efforts beginning with a relatively small group of women in Italy, The Wages for Housework Campaign was successful in mobilizing on an international level. A Wages for Housework group was founded in Brooklyn, New York with the help of Federici.[12] As Heidi Hartmann acknowledges (1981), the efforts of these movements, though ultimately unsuccessful, generated important discourse regarding the value of housework and its relation to the economy.[8]

Sharing the responsibility of reproductive labour

Another solution proposed by Marxist feminists is to liberate women from their forced connection to reproductive labour. In her critique of traditional Marxist feminist movements such as the Wages for Housework Campaign, Heidi Hartmann (1981) argues that these efforts "take as their question the relationship of women to the economic system, rather than that of women to men, apparently assuming the latter will be explained in their discussion of the former."[8] Hartmann (1981) believes that traditional discourse has ignored the importance of women's oppression as women, and instead focused on women's oppression as members of the capitalist system. Similarly, Gayle Rubin, who has written on a range of subjects including sadomasochism, prostitution, pornography, and lesbian literature as well as anthropological studies and histories of sexual subcultures, first rose to prominence through her 1975 essay The Traffic in Women: Notes on the 'Political Economy' of Sex,[13] in which she coins the phrase "sex/gender system" and criticizes Marxism for what she claims is its incomplete analysis of sexism under capitalism, without dismissing or dismantling Marxist fundamentals in the process.

More recently, many Marxist feminists have shifted their focus to the ways in which women are now potentially in worse conditions after gaining access to productive labour. Nancy Folbre proposes that feminist movements begin to focus on women's subordinate status to men both in the reproductive (private) sphere, as well as in the workplace (public sphere).[14] In an interview in 2013, Silvia Federici urges feminist movements to consider the fact that many women are now forced into productive and reproductive labour, resulting in a "double day".[15] Federici argues that the emancipation of women still cannot occur until they are free from their burdens of unwaged labour, which she proposes will involve institutional changes such as closing the wage gap and implementing child care programs in the workplace.[15] Federici's suggestions are echoed in a similar interview with Selma James (2012) and these issues have been touched on in recent presidential elections.[10]

Affective Labor

Feminist scholars and sociologists such as Michael Hardt[16], Antonio Negri[16], Arlie Russell Hochschild[17] and Shiloh Whitney[18] discuss a new form of labor that transcends the traditional spheres of labor and which does not create product, or is byproductive. [18] Affective labor focuses on the blurred lines between personal life and economic life. Whitney states "The daily struggle of unemployed persons and the domestic toil of housewives no less than the waged worker are thus part of the production and reproduction of social life, and of the biopolitical growth of capital that valorizes information and subjectivities."[18] The concept of emotional labor is a focus of affective labor, particularly the emotional labor that is present and required in traditionally pink collared jobs (jobs traditionally occupied by women). Arlie Russell Hochschild discusses the emotional labor of flight attendants in her book The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling (1983)[17] in which she considers the affective labor of the profession as flight attendants smile, exchange pleasantries and banter with customers.

Intersectionality and Marxist feminism

With the emergence of Intersectionality[19] as a widely popular theory of current feminism, Marxist feminists are broadening their focus to include persons that would be at an increased risk for exploitation in a capitalist system while also remaining critical of intersectionality theory for relying on bourgeois identity politics.[20] The current organization Radical Women provides a clear example of successful incorporation of the goals of Marxist feminism without overlooking identities that are more susceptible to exploitation. They contend that elimination of the capitalist profit-driven economy will remove the motivation for sexism, racism, homophobia, and other forms of oppression.[21]

Marxist feminist critiques of other branches of feminism

Clara Zetkin[22][23] and Alexandra Kollontai[24][25] were opposed to forms of feminism that reinforce class status. They did not see a true possibility to unite across economic inequality because they argue that it would be extremely difficult for an upper class woman to truly understand the struggles of the working class.

"For what reason... should the woman worker seek a union with the bourgeois feminists? Who, in actual fact, would stand to gain in the event of such an alliance? Certainly not the woman worker." — Alexandra Kollontai, 1909[24]

Critics like Kollontai (1909) believed liberal feminism would undermine the efforts of Marxism to improve conditions for the working class. Marxists supported the more radical political program of liberating women through socialist revolution, with a special emphasis on work among women and in materially changing their conditions after the revolution. Additional liberation methods supported by Marxist feminists include radical demands coined as "Utopian Demands" by Maria Mies.[26] This indication of the scope of revolution required to promote change states that demanding anything less than complete reform will produce inadequate solutions to long-term issues.

Notable Marxist feminists

See also

References

- ↑ Desai, Murli (2014), "Feminism and policy approaches for gender aware development", in Desai, Murli, ed. (2014). The paradigm of international social development: ideologies, development systems and policy approaches. New York: Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 9781135010256.

- 1 2 3 4 Ferguson, Ann; Hennessy, Rosemary (2010), "Feminist perspectives on class and work", in Stanford Uni (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ Marx, Karl; Engels, Frederick (1848). The Communist Manifesto. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. OCLC 919388374. View online.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1904) [1859]. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co. OCLC 896669199. View online.

- ↑ Lenin, Vladimir (1917). The State and Revolution: The Marxist Theory of the State & The Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution. London: George Allen & Unwin. OCLC 926871435. View online.

- ↑ Engels, Frederick (1902) [1884]. The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co. OCLC 213734607. View online.

- 1 2 Vogel, Lise (2013), "A decade of debate", in Vogel, Lise (ed.). Marxism and the oppression of women: toward a unitary theory. Leiden, Holland: Brill. p. 17. ISBN 9789004248953.

- Citing:

- Benston, Margaret (September 1969). "The political economy of women's liberation". Monthly Review. Monthly Review Foundation. 21 (4): 13&ndash, 27. doi:10.14452/MR-021-04-1969-08_2.

- Morton, Peggy (May 1970). "A woman's work is never done" [The production, maintenance and reproduction of labor power]. Leviathan. 2. OCLC 741468359.

- Reproduced as: Morton, Peggy (1972), "Women's work is never done... or The production, maintenance and reproduction of labour power", in Various, Women unite! (Up from the kitchen. Up from the bedroom. Up from under.) An anthology of the Canadian Women's Movement, Toronto: Canadian Women's Education Press, OCLC 504303414

- Citing:

- 1 2 3 4 Hartmann, Heidi (1981), "The unhappy marriage of Marxism and feminism: towards a more progressive union", in Sargent, Lydia, Women and revolution: a discussion of the unhappy marriage of Marxism and Feminism, South End Press Political Controversies Series, Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press, pp. 1&ndash, 42, ISBN 9780896080621.

- Reproduced as: Hartmann, Heidi (2013), "The unhappy marriage of Marxism and feminism: towards a more progressive union", in McCann, Carole; Kim, Seung-kyung, Feminist theory reader: local and global perspectives, New York: Routledge, pp. 187&ndash, 199, ISBN 9780415521024

- ↑ Gilman, C. P. (1898). Women and economics: a study of the economic relation between men and women as a factor in social evolution. Boston: Small, Maynard, & Co. OCLC 26987247.

- 1 2 Gardiner, Becky (8 June 2012). "A life in writing: Selma James". The Guardian.

- ↑ Dalla Costa, Mariarosa; James, Selma (1972). The power of women and the subversion of the community. Bristol, England: Falling Water Press. OCLC 67881986.

- 1 2 Cox, Nicole; Federici, Silvia (1976). Counter-planning from the kitchen: wages for housework: a perspective on capital and the left (PDF) (2nd ed.). New York: New York Wages for Housework. OCLC 478375855.

- ↑ Rubin, Gayle (1975), "The Traffic in Women: Notes on the 'Political Economy' of Sex", in Reiter, Rayna (ed.). Toward an Anthropology of Women. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 9780853453727.

- Reprinted in: Nicholson, Linda (1997). The second wave: a reader in feminist theory. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415917612.

- ↑ Folbre, Nancy (1994). Who pays for the kids?: gender and the structures of constraint. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415075657.

- See also: Baker, Patricia (Autumn 1996). "Reviewed work Who Pays for the Kids? Gender and the Structures of Constraint by Nancy Folbre". Canadian Journal of Sociology. University of Alberta. 21 (4): 567–571. doi:10.2307/3341533. JSTOR 3341533.

- 1 2 Vishmidt, Marina (7 March 2013). "Permanent reproductive crisis: an interview with Silvia Federici". Mute.

- 1 2 Michael., Hardt, (2000). Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674251210. OCLC 1051694685.

- 1 2 Brown, J. V. (1985-09-01). "The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. By Arlie Russell Hochschild. University of California Press, 1983. 307 pp. $14.95". Social Forces. 64 (1): 223–224. doi:10.1093/sf/64.1.223. ISSN 0037-7732.

- 1 2 3 Whitney, Shiloh (2017-12-14). "Byproductive labor". Philosophy & Social Criticism. 44 (6): 637–660. doi:10.1177/0191453717741934. ISSN 0191-4537.

- ↑ Crenshaw, Kimberle (1991-07). "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color". Stanford Law Review. 43 (6): 1241. doi:10.2307/1229039. ISSN 0038-9765. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Mitchell, Eve (2013). I am a woman and a human: a Marxist feminist critique of intersectionality (pamphlet). Houston, NYC, and Atlanta: Unity and Struggle. Archived from the original on 2017-05-29. Pdf of pamphlet.

- ↑ Cornish, Megan (2001), "Introduction", in Radical Women, Radical Women (ed.). The Radical Women manifesto: socialist feminist theory, program and organizational structure. Seattle, Washington: Red Letter Press. pp. 5&ndash, 16. ISBN 9780932323118.

- ↑ Zetkin, Clara (1895). On a bourgeois feminist petition.

- Cited in: Draper, Hal; Lipow, Anne G. (1976). "Marxist women versus bourgeois feminism". The Socialist Register. Merlin Press Ltd. 13: 179&ndash, 226. Pdf.

- ↑ Zetkin, Clara (1966) [1920]. Lenin on the women’s question. New York, N.Y.: International Publishers. OCLC 943938450.

- 1 2 Kollontai, Alexandra (1977) [1909]. The social basis of the woman question. Allison & Busby. OCLC 642100577.

- ↑ Kollontai, Alexandra (1976) [1919]. Women workers struggle for their rights. London: Falling Wall Press. OCLC 258289277.

- ↑ Mies, Maria (1981), "Utopian socialism and women's emancipation", in Mies, Maria; Jayawardena, Kumari, Feminism in Europe: liberal and socialist strategies 1789-1919, History of the Women's Movement, The Hague: Institute of Social Studies, pp. 33&ndash, 80, OCLC 906505149

Further reading

- Poonacha, Veena (13 March 1993). "Hindutva's hidden agenda: why women fear religious fundamentalism". Economic and Political Weekly. Sameeksha Trust (India). 28 (11): 438&ndash, 439.

- Cited in:

- Louis, Prakash (2005), "Hindutva and weaker sections: conflict between dominance and resistance", in Puniyani, Ram (ed.). Religion, power & violence: expression of politics in contemporary times. New Delhi Thousand Oaks: Sage. p. 171. ISBN 9780761933380.

- Cited in:

External links

- Marxism, Liberalism, And Feminism (Leftist Legal Thought) New Delhi, Serials (2010) by Dr.Jur. Eric Engle LL.M.

- Proletarian Feminism

- Silvia Federici, recorded live at Fusion Arts, NYC. 11.30.04

- Marxist Feminism

- Feminism of the Anti-Capitalist Left by Lidia Cirillo