Christian feminism

Christian feminism is a school of Christian theology which seeks to advance and understand the equality of men and women morally, socially, spiritually, and in leadership from a Christian perspective.[1] Christian feminists argue that contributions by women in that direction are necessary for a complete understanding of Christianity.[2] Christian feminists believe that God does not discriminate on the basis of biologically-determined characteristics such as sex and race.[3] Their major issues include the ordination of women, biblical equality in marriage, recognition of equal spiritual and moral abilities, reproductive rights, and the search for a feminine or gender-transcendent divine.[4][5][6][7] Christian feminists often draw on the teachings of other religions and ideologies in addition to biblical evidence.[8]

The term Christian egalitarianism is often preferred by those advocating gender equality and equity among Christians who do not wish to associate themselves with the feminist movement.[9]

History

Some Christian feminists believe that the principle of egalitarianism was present in the teachings of Jesus and the early Christian movements, but this is a highly contested view. These interpretations of Christian origins have been criticized by secular feminists for "anachronistically projecting contemporary ideals back into the first century."[10] In the Middle Ages Julian of Norwich and Hildegard of Bingen explored the idea of a divine power with both masculine and feminine aspects.[11][12] Feminist works from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries addressed objections to women learning, teaching and preaching in a religious context.[13] One such proto-feminist was Anne Hutchinson who was cast out of the Puritan colony of Massachusetts for teaching on the dignity and rights of women.[14]

The first wave of feminism in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries included an increased interest in the place of women in religion. Women who were campaigning for their rights began to question their inferiority both within the church and in other spheres justified by church teachings.[15] Some Christian feminists of this period were Marie Maugeret, Katharine Bushnell, Catherine Booth, Frances Willard, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Issues

Christianity and gender | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theology | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Four major positions | ||||||||||

| Church and society | ||||||||||

| Organizations | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Theologians and authors | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Women in church leadership

In both mainline and liberal branches of Protestant Christianity, women are ordained as clergy. Even some theologically conservative denominations, such as The Church of the Nazarene[16] and Assemblies of God,[17] ordain women as pastors. However, the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Southern Baptist Convention (the largest Protestant denomination in the U.S.),[18] as well as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and many churches in the American Evangelical movement prohibit women from entering clerical positions.[19] Some Christian feminists believe that as women have greater opportunity to receive theological training, they will have greater influence on how scriptures are interpreted by those that deny women the right to become ministers.[20]

Women as spiritually deficient

Understanding whether women are spiritually deficient to men partly hinges on whether women are equipped spiritually with discernment to teach. The following passages also relate to whether women are inherently spiritually discerning as men:

- Galatians 3:28. "There is neither…male nor female for all are one in Christ Jesus."

- Deborah of the Old Testament was a prophetess and "judge of Israel"[21]

- Genesis 2:20. The word translated "help" or "helper" is the same Hebrew word, "ēzer," which the Old Testament uses more than 17 times to describe the kind of help that God brings to His people in times of need; e.g., "Thou art my help (ēzer) and my deliverer," and "My help (ēzer) comes from the Lord." Never once in all these references is the word used to indicate subordination or servitude to another human being.[22]

- Genesis 3:16. "To the woman he (God) said, 'I will greatly increase your pains in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children, yet your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.'"

- 1 Timothy 2:12. "But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence."

- 1 Corinthians 11:7-9. "For a man ought not to cover his head, since he is the image and glory of God, but woman is the glory of man. For man was not made from woman, but woman from man. Neither was man created for woman, but woman for man."

- 1 Corinthians 14:34. "The women should keep silent in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but should be in submission, as the Law also says."

- Colossians 3:18. "Wives, submit to your husbands, as is fitting in the Lord."

- 1 Peter 3:1. "Likewise, wives, be subject to your own husbands, so that even if some do not obey the word, they may be won without a word by the conduct of their wives."

- Ephesians 5:22-24. "Wives, be subject to your husbands as you are to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife just as Christ is the head of the church, the body of which he is the Savior. Just as the church is subject to Christ, so also wives ought to be, in everything, to their husbands."

Reproduction, sexuality and religion

Conservative religious groups are often at philosophical odds with many feminist and liberal religious groups over abortion and the use of birth control. Scholars like sociologist Flann Campbell have argued that conservative religious denominations tend to restrict male and female sexuality[23][24] by prohibiting or limiting birth control use,[25] and condemning abortion as sinful murder.[26][27] Some Christian feminists (like Teresa Forcades) contend that a woman's "right to control her pregnancy is bounded by considerations of her own well-being" and that restricted access to birth control and abortion disrespect her God-given free will.[28]

A number of socially progressive mainline Protestant denominations as well as certain Jewish organizations and the group Catholics for a Free Choice have formed the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice.[29] The RCRC often works as a liberal feminist organization and in conjunction with other American feminist groups to oppose conservative religious denominations which, from their perspective, seek to suppress the natural reproductive rights of women.[30]

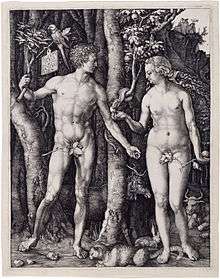

Feminine or gender-transcendent God

Some Christian feminists believe that gender equality within the church cannot be achieved without rethinking the portrayal and understanding of God as a masculine being.[31] The theological concept of Sophia, usually seen as replacing the Holy Spirit in the Trinity, is often used to fulfill this desire for symbols which reflect women's religious experiences. How Sophia is configured is not static, but usually filled with emotions and individual expression.[32] For some Christian feminists, the Sophia concept is found in a search for women who reflect contemporary feminist ideals in both the Old and New Testament. Some figures used for this purpose include the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene,[33] Eve,[34] and Esther.[35] Others see God as entirely gender-transcendent,[36] or focus on the feminine aspects of God and Jesus.[37] Some Christian feminists use and promote gender-neutral or feminine language and imagery to describe God or Christ. The United Church of Christ describes its New Century Hymnal, published in 1995, as "the only hymnal released by a Christian church that honors in equal measure both male and female images of God."[38]

See also

- Asian feminist theology

- Anti-pornography feminism

- Biblical patriarchy

- Christian egalitarianism

- Christian humanism

- Christianity and abortion

- Christian views of marriage

- Complementarianism

- Evangelical and Ecumenical Women's Caucus

- Feminist theology

- Gender roles in Christianity

- HerChurch

- Liberation theology

- Mormon feminism

- New feminism

- Ordination of women

- Political theology

- Progressive Christianity

- Sacred feminine

- Women in the Bible

- Women in Church history

References

- ↑ Hassey, Janette (1989). "A BRIEF HISTORY OF CHRISTIAN FEMINISM". Transformation. 6 (2): 1–5.

- ↑ Harrison, Victoria S. "Modern Women, Traditional Abrahamic Religions and Interpreting Sacred Texts." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 15.2 (2007):145-159.

- ↑ McPhillips, Kathleen. "Theme: Feminisms, Religions, Cultures, Identities." Australian Feminist Studies 14.30 (1999).

- ↑ Daggers, Jenny. "Working for Change in the Position of Women in the Church." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 26 (2001)

- ↑ McEwan, Dorothea. "The Future of Christian Feminist Theologies--As I Sense It: Musings on the Effects of Historiography and Space."

- ↑ McIntosh, Esther. "The Possibility of a Gender-Transcendent God: Taking Macmurray Forward." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 15 (2007): 236-255.

- ↑ Polinska, Wioleta. "In Woman's Image: An Iconography for God." Feminist Theology 13.1 (2004):40-61

- ↑ Clack, Beverly. "Thealogy and Theology: Mutually Exclusive or Creatively Interdependent? Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 21 (1999):21-38.

- ↑ Groothuis, Rebecca M., Ronald Pierce and Gordon Fee (eds.), Feminism Goes to Seed Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Beavis, Mary Ann. "Christian Origins, Egalitarianism, and Utopia." Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 23.2 (2007): 27-49

- ↑ Bauerschmidt, Frederick Christian. "Seeing Jesus: Julian of Norwich and the Text of Christ's Body." Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 27.2 (1997):189-214.

- ↑ Boyce-Tillman, June. "Hildegard of Bingen: A Woman for our Time." Feminist Theology 22 (1999):25-41.

- ↑ McEwan, Dorothea. "The Future of Christian Feminist Theologies--As I Sense It: Musings on the Effects of Historiography and Space." 79-92.

- ↑ Ellsberg, Robert. All Saints: Daily Reflections on Saints, Prophets, and Witnesses from Our Time

- ↑ Capitani, Diane. "Imagining God in Our Ways: The Journals of Frances E. Willard." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 12.1 (2003):57-88.

- ↑ Church of the Nazarene Manual. Kansas City, MO: Nazarene Publishing House. 2017. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-8341-3711-0. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Role of Women in Ministry" (PDF). The General Council of the Assemblies of God. 1990-08-14. p. 7.

- ↑ SBC Position Statements - Women in Ministry

- ↑ SpringerLink - Journal Article

- ↑ Harrison, Victoria S. "Modern Women, Traditional Abrahamic Religions and Interpreting Sacred Texts." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 15.2 (2007):145-159

- ↑ Deborah the Prophetess Archived 2007-12-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Ezer Kenegdo" Word Study. God's Word to Women, 2011

- ↑ Campbell, Flann (1960). "Birth Control and the Christian Churches". Population Studies. 14 (2): 131–47. doi:10.2307/2172010. ISSN 0032-4728. JSTOR 2172010 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

- ↑ Ordaining Women: Culture and Conflict in Religious Organizations

- ↑ Paul VI - Humanae Vitae Archived 2011-03-19 at WebCite

- ↑ Southern Baptist Convention Resolutions on Abortion

- ↑ Sin of Abortion and the Reasons Why Archived 2007-08-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Colker, Ruth. "Feminism, Theology, and Abortion: Toward Love, Compassion, and Wisdom." California Law Review 77 (1989):1011-1075.

- ↑ RCRC—Member Organizations Archived 2007-03-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ National Women's Law Center

- ↑ Kim, Grace. "Revisioning Christ". Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 28 (2001):82–91.

- ↑ McEwan, Dorothea. "The Future of Christian Feminist Theologies--As I Sense It: Musings on the Effects of Historiography and Space." 79–92.

- ↑ Winkett, Lucy. "Go Tell! Thinking About Mary Magdalene." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 29 (2002):19-31.

- ↑ Isherwood, Lisa. "The British Christian Women's Movement: A Rehabilitation of Eve." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 15.1 (2006): 128-129.

- ↑ Fuchs, Esther. "Reclaiming the Hebrew Bible for Women." Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 24.2 (2008):45-65.

- ↑ McIntosh, Esther. "The Possibility of a Gender-Transcendent God: Taking Macmurray Forward." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 15 (2007):236–255.

- ↑ Kim, Grace. "Revisioning Christ." Feminist Theology: The Journal of the Britain & Ireland School of Feminist Theology 28 (2001):82–91.

- ↑ http://www.ucc.org/about-us/old-firsts.html

Further reading

- Anderson, Pamela Sue (1998). A feminist philosophy of religion: the rationality and myths of religious belief. Oxford, UK Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell. ISBN 9780631193838.

- Anderson, Pamela Sue; Clack, Beverley, eds. (2004). Feminist philosophy of religion: critical readings. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415257503.

- Berliner, Patricia M. (2007). Touching your lifethread and revaluing the feminine: a process of psychospiritual change. South Bend, Indiana: Cloverdale Books. ISBN 9781929569229.

- Bristow, John T. (1991). What Paul really said about women: an apostle's liberating views on equality in marriage, leadership, and love. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 9780062116598.

- Davies, Eryl W. (2003). The dissenting reader: feminist approaches to the Hebrew Bible. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate. OCLC 607075403.

- Gentry, Caron E. (2016). "Feminist Christian realism: vulnerability, obligation and power politics". International Feminist Journal of Politics. 18 (3): 449&ndash, 467. doi:10.1080/14616742.2015.1059144. hdl:10023/10079.

- Haddad, Mimi (Autumn 2006). "Egalitarian pioneers: Betty Friedan or Catherine Booth?" (PDF). Priscilla Papers. 20 (4): 53&ndash, 59.

- Radford Ruether, Rosemary (2007). Feminist theologies: legacy and prospect. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. ISBN 9780800638948.

- Russell, Letty M. (1993). Church in the round: feminist interpretation of the church. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster/J. Knox Press. ISBN 9780664250706.

- Wilson-Kastner, Patricia (1983). Faith, feminism, and the Christ. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. ISBN 9780800617462.

External links

- Christian feminist articles and books

- Radio Interview with Dr. Rosemary Radford Ruether on Ecofeminism and Christianity, University of Toronto, 16 February 2007.