Malmesbury

| Malmesbury | |

|---|---|

Malmesbury Abbey | |

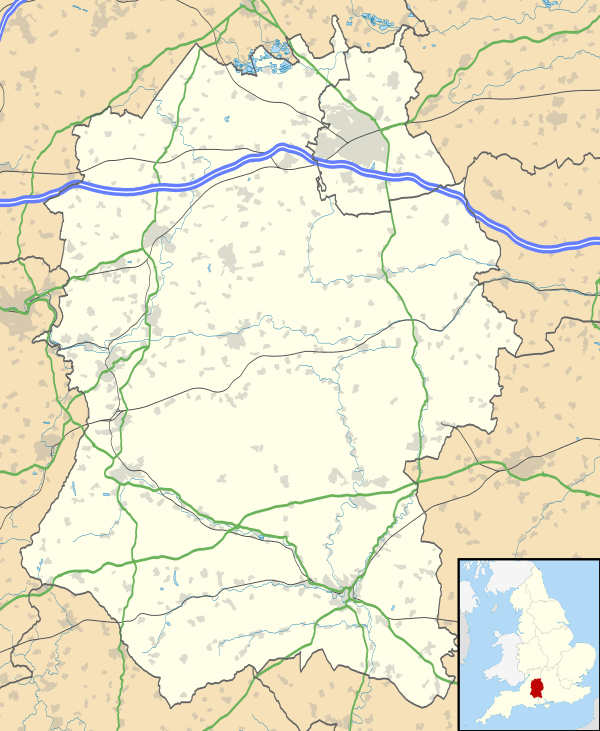

Malmesbury Malmesbury shown within Wiltshire | |

| Population | 5,380 (2011 census)[1] |

| Demonym | Jackdaws (in informal contexts — blason populaire) |

| OS grid reference | ST940857 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Malmesbury |

| Postcode district | SN16 |

| Dialling code | 01666 |

| Police | Wiltshire |

| Fire | Dorset and Wiltshire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| EU Parliament | South West England |

| UK Parliament | |

Malmesbury (/ˈmɑː(l)mzbəri/) is a market town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. Technology company Dyson is headquartered in Malmesbury, which remains a market town and became prominent in the Middle Ages as a centre for learning focused on and around Malmesbury Abbey, the bulk of which forms a rare survival of the dissolution of the monasteries. Once the site of an Iron Age fort, in the Anglo-Saxon period it became the site of a monastery famed for its learning and one of Alfred the Great's fortified burhs for defence against the Vikings. Æthelstan, the first king of England, was buried in Malmesbury Abbey when he died in 939.

History

The hilltop contains several freshwater springs,[2] which helped early settlements. It was the site of an Iron Age fort,[3] and in the Anglo-Saxon period it had a monastery famed as a centre of learning. The town is listed in the Burghal Hidage as one of Alfred the Great's defended burhs assessed at 1200 hides, its Iron Age defences helping to provide protection against Viking attack. The town was described in Domesday Book as a borough.[4] Alfred's grandson, Æthelstan, the first king of England, was buried in Malmesbury Abbey in 939.[5]

Until 1934 the west end of the town was administered as the separate parish of Westport St Mary[6]

Malmesbury Abbey

The Abbey was founded in 675 by Maildubh, Mailduf or Maelduib, an Irishman.[7] After the death of Maidulph around 700, Aldhelm became the first abbot and built the first church organ in England, which was described as a "mighty instrument with innumerable tones, blown with bellows, and enclosed in a gilded case."[8] Having founded other churches in the area, including at Bradford on Avon, he died in 709 and was canonised.[8] Its architecture is listed in the highest category and it is a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[9] Across the River Avon's Sherston branch via the footpath by 18 Gloucester Street (leading south-west) is a depression Daniels Well and a farm beyond it is named after this.[10] This derives from a monk called Daniel named after earlier Daniel of Winchester.[11] This former bishop, on losing his sight, lived at the abbey briefly until death in 745AD and was educated there. The later monk is said to have submerged himself in the cold water every day for decades to quell fiery passions. The Abbey was the site of an early attempt at human flight, when noted by historian William of Malmesbury (1095–1143) in 1010, the monk Eilmer of Malmesbury flew a primitive hang glider from a tower. Eilmer flew over 180 metres before landing, breaking both legs.[8]

Thus by the time of the Norman invasion in 1066, Malmesbury was one of the most significant towns in England. It is listed first (i.e., most important) in the Wiltshire section of Domesday Book. King Henry I's chancellor, Roger of Salisbury, seized the monastery under his bishopric in 1118, and held it for 20 years. Renowned as a great builder, he rebuilt the wooden town walls wholly in stone rather than wood, constructing Malmesbury Castle at the same time.

By the Dark Ages, the north of the town was heavily developed as a religious centre, resulting in the construction of the third Abbey on the site, the 12th century Malmesbury Abbey, which had a spire 7 metres (23 ft) taller than the 123 metres (404 ft) one of Salisbury Cathedral.[8] In 1220 this resulted in the construction of the Abbey guest house, which is now The Old Bell hotel which claims to be the oldest hotel in England. The Abbey's spire collapsed in either the late 15th or early 16th century. Under his English Reformation, King Henry VIII, sold the substantial land, but retaining a minor choice portion, to a local clothier William Stumpe. The extant part of the Abbey is now the parish church, with the remains containing a parvise which still holds some fine examples of books from the former Abbey library.

Malmesbury natives can be nicknamed Jackdaws, originating from the avian colony of these that inhabit the Abbey walls and roof.[12]

Battles

The community was the ancient frontier of two kingdoms, with Tetbury 5 miles (8.0 km) to the north in Mercia while Malmesbury was in the West Saxon Kingdom, resulting in centuries of animosity between the two towns.[13] The location and defensive position of Malmesbury on the latterly important Oxford to Bristol route made it a strategic military point. During the 12th century civil war between Stephen of England and his cousin the Empress Matilda, the succession agreement between Stephen and Henry of Anjou (later Henry II) was reached after their armies faced each other across the impassable River Avon at Malmesbury in the winter of 1153, with Stephen losing by refusing battle.

During the Civil War the town changed hands seven times, with the south face of Malmesbury Abbey still today bearing pock-marks from cannon and gunshot. In 1646 Parliament ordered that the town walls be destroyed. As peace came to inland England, and the need to defend the developing coastal port towns became more important, Malmesbury, without its Abbey, lost its importance. As developing transport and trade routes passed it by, it regressed to a regional market town.

Malmesbury Commoners

At the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, King Athelstan of Wessex defeated an army of northern English and Scots and made a claim to become the first 'King of All England'. Helped by many men from Malmesbury, in gratitude he gave the townsfolk their freedom, along with 600 hides of land to the south of the town. The status of freemen of Malmesbury was passed down through the generations and remains to this day. It is likely, however, that the title of freeman, or commoner, was given to tradesmen and craftsmen coming into the town during the early Middle Ages, so the claim of direct lineage from the men who fought with King Athelstan to the present day commoners is unlikely, though possible. Since at least the 17th century, however, the right has been only handed down from father to son or son-in-law. There is a maximum of 280 commoners. The organisation is said to be the 'most exclusive club' in the world, as to enter it one has to be born to a freeman or marry the daughter of one.

Since 2000, and with the possibility of falling numbers, women were admitted for the first time – the daughters of freemen. The organisation, The Warden and Freemen of Malmesbury, still owns the land to the south of the town, along with dozens of properties, pubs and shops within the town itself, providing affordable housing to townsfolk.

Government

Malmesbury Town Council, formed as successor to the municipal borough, is made up of sixteen councillors, who elect annually a town mayor and deputy town mayor from their number.

For elections to Wiltshire Council, Malmesbury forms one electoral division, returning a single unitary councillor. Gavin Grant, a Liberal Democrat, was elected in 2017.[14]

Nationally at UK Government level in the House of Commons, Malmesbury is part of the North Wiltshire constituency, represented since 1997 by James Gray (Conservative Party).

Malmesbury is twinned with Niebüll in Germany, and Gien in France.[15]

Geography

Malmesbury sits on a flat Cotswolds hilltop at the convergence of two rivers. From the west, the infant (Bristol) Avon flows from Sherston, and from the north west, a tributary either known as the Tetbury Avon, River Avon (Tetbury branch) or, locally, The Ingleburn. They flow within 200 metres (660 ft) of each other but are separated by a narrow and high isthmus which forces the Bristol Avon south and the Tetbury Avon east.[16] This creates a rocky outcrop as a south-facing, gently sloping hilltop, until the two rivers meet on the southern edge of the town. With steep sides, in places cliff-like, the town was described by Sir William Waller as the best naturally defended inland location he had seen.[17]

In the 19th and 20th centuries the town expanded to the northwest, occupying land between the two rivers which was formerly in Westport and Brokenborough parishes.[16] In the later 20th and early 21st, development was to the north, as far as the area known as Filands[18] which is bounded by the B4014 road.

Demography

In 2011 the population reached 5,380 living in 2,280 homes. The additional figures are given for The Abbey, the supplemental ecclesiastical parish added to that of St Paul when this existed. Figures from 1911 are for metropolitan borough and after 1961 for ward. For 1901 the area was split into three respective parishes, St Paul Within, St Paul Without and Abbey so three figures are given in the correct order as stated.[1]

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1881 | 1891 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1,491 + 80 | 1,609 + 137 | 1,976 + 169 | 2,169 +124 | 2,367 + 131 | 2,443 + 138 | 2,220 + 150 | 2,144 + 119 | |

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | 1951 | 1961 | 2001 | 2011 |

| Population | 1,181 + 974 + 106 | 2,656 | 2,407 | 2,334 | 2,464 | 2,510 | 4,631 | 2,610 | 5,380 |

Economy

Traditionally a market town serving the rural area of north west Wiltshire, farming has been the main industry. Even today, the High Street has numerous independent shops and a regular weekly market. The Reformation of 1539 brought about a change in the economy of Malmesbury: having no income from the Abbey, the town turned to the wool spinning and weaving industry, having access to large quantities of wool and water. It then became a centre of the lace-making industry. But, what had made it successful and important as a religious and strategic defensive centre – water on three sides and steep cliffs – precluded easy access for the modern bulk transport methods of canals and railways. Hence the Kennet and Avon Canal and the later Great Western Railway passed well to the south of the town; while local quarrying of cotswold stone provided often transient booms in employment, Malmesbury saw little expansion compared to, for example, Gloucester, by not being a commuter suburb or major production centre of the industrial revolution.

The town's main employer today is Dyson, which has its headquarters on the edge of the town, and employs around 1,600 people. The HQ is mainly a design organisation, with manufacturing carried out in Malaysia.

The town's economy profits from tourism, divided among Cotswold Hills retreats (ranging from B&Bs to golf/spa resorts), visits and tours of the abbey, nearby landmarks and festivals or by interest in the counter-modernism 1960s work of poet laureate, John Betjeman.

Malmesbury has benefited from a 24.95% increase in property value in the last 10 years, according to Zoopla.

Malmesbury had a nine-day wonder media event in January 1998, when two Tamworth pigs known as the Tamworth Two escaped from the town's abattoir. They swam the Tetbury branch of the River Avon, across a few fields and lived in an orchard for a week. The story made international headlines with tabloid newspapers and TV news stations fighting each other to sight and then capture the pigs.

EKCO factory

At the beginning of the World War II, the electronics company EKCO moved part of its operations from Southend-on-Sea to Cowbridge House, 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) southeast of the town, to avoid the danger of bombing.[20] The company established a shadow factory to produce radar equipment, then a new technology. The factory continued production after the war, was taken over by Pye TMC and then Philips, and later became part of AT&T. The site was in use as offices until 2004 when the owners, Lucent Technologies, moved their operations to Swindon.

Culture and community

Malmesbury has a thriving carnival, which takes place in the last two weeks of August, with the finale procession through the town held on the first Saturday in September. It has grown in recent years to now include more than 30 events, ranging from music events to an attempt on the world record for the largest pillow fight.

The world music festival Womad Charlton Park has been held in Charlton Park near Malmesbury since 2007.

Sport and leisure

Malmesbury has a non-League football team Malmesbury Victoria F.C., who play at The Flying Monk Ground.[21] A swimming club, 'Malmesbury Marlins', train at The Activity Zone leisure centre. Malmesbury Cricket Club are an ECB Clubmark accredited sports club who play at The Wortheys sports ground, with adult and junior teams playing in the Wiltshire Leagues.[22]

Planning

In 2011 Malmesbury was chosen by the Department for Communities and Local Government as a "front-runner" area to test Neighbourhood Planning powers introduced in the Localism Act 2011.[23] As part of the neighbourhood planning process in February 2012 a series of seminars and workshops involving residents and stakeholders were run in Malmesbury by The Prince's Foundation for Building Community.[24] In March 2012 issues of planning in Malmesbury were featured as part of the wider national debate about changes to the planning system and the balance of power between communities and developers.[25]

Landmarks

What made Malmesbury successful as a town – water and excellent defences – led to both its current layout and the presence of over 300 listed buildings within its boundaries.[26] Roger of Salisbury reconstructed the town after his accession to Bishop of Salisbury in 1102, and the Saxon layout he rebuilt is retained in the centre today. The geography also precluded easy development for mass transport and hence hindered industrial development, leaving the architecture and ancient buildings largely untouched. The result is a higher proportion of Grade I and Grade II buildings than in many other English towns.

Grade I listed

The parish has six Grade I listed structures, all within the hilltop town.

Malmesbury Abbey

The surviving nave of the 12th-century abbey church, built in limestone ashlar with stone tiles, serves as the parish church. In the period 1350–1450 the building was enlarged and a clerestory, crossing spire and west towers were added; the spire fell in 1479. After the Dissolution, William Stumpe reduced and altered the building to form the parish church. The west tower fell c. 1662.[27]

Features of the building include the south porch, richly carved with Biblical scenes, which Pevsner describes as "among the best pieces of Norman sculpture and decoration in England".[28]

Market Cross

In the centre of the town stands the market cross, built c. 1490, possibly using stone salvaged from the recently ruined part of the abbey. It was described by John Leland, writing in the 1540s, as a "right fair and costely peace of worke", which was built to shelter the "poore market folkes" when "rayne cummith".[29] An elaborately carved octagonal structure, it is recognised as one of the best preserved of its kind in England. It still serves as a public shelter today, nicknamed "The Birdcage" because of its appearance.[30]

Numbers 1 and 3 Market Cross are also listed buildings, as is the former Abbey Brewery opposite.[31]

St Paul's bell tower

The 15th-century three-stage tower is all that remains of St Paul's church, which stood adjacent to the abbey and was the town's parish church until 1541, when that role was transferred to the former abbey church. The nave of St Paul's had collapsed by the early 16th century, and the remainder was used for a time as a private house and town hall; the chancel was pulled down in 1852.[32] Today it serves as the bell tower for the abbey.

Abbey House

Abbey House was rebuilt c. 1540 by William Stumpe or his son James, on the site of a 13th-century building within the abbey grounds; Harold Brakspear carried out 20th-century enlargement.[33] Today Abbey House Gardens are operated as a tourist attraction.

The Old Bell hotel

The former guest house for the abbey dates from the early 13th century. The building was extended and altered in the late 15th century or early 16th, and from c. 1530 it was used as a cloth mill by William Stumpe. Further alterations were made in the 17th century and in 1908. There is a fine ashlar fire hood of c. 1220.[34] Today the building is a hotel, The Old Bell.

Former court house

From the 13th century or earlier, there was a hospital of St John the Baptist in the south of the town. In the 16th century the hospital was bought by the corporation, who used part of it for meetings of the borough court from 1616. The former court house, in limestone rubble with a 15th-century roof and retaining some 17th and 18th-century court fittings, is now part of a dwelling.[35][36] Nearby is the 12th-century entrance arch of the hospital and the 16th-century almshouses, in use until 1948; now three cottages, Grade II* listed.[37]

Other buildings

A large building of medieval origins, now a private home, Tower House stands at the end of Oxford Street. It contains a high-roofed main hall where it is said Henry VIII dined after hunting in nearby Bradon Forest. In the 1840s, a doctor living in the house, with a passion for astronomy, built a narrow tower protruding high from the roof. The Grade II* listed building dominates the skyline of the east of the town.[38]

Transport

Malmesbury railway station opened on 17 December 1877. The Malmesbury branch was built largely by the Malmesbury Railway Company, and was completed by the Great Western Railway which absorbed the Malmesbury Railway Company in May 1877 when the latter could not raise sufficient funds to complete the line.[39] The branch split from the main London-Bristol line at Dauntsey, although a later connection with the northern GWR 'mainline' to the Severn Tunnel and South Wales was made at Little Somerford. Just short of its terminus, the line ran through a short tunnel: the only tunnel on the line between Malmesbury and Paddington. The station closed to passengers in 1951 (their last day was 8 September), and freight in 1962. The tracks were used for a period to test new diesel locomotives built by Swindon railway works, but lifted in the 1970s, and the site of the station is now an industrial estate. The nearest stations today, all served by Great Western Railway, are:

- Chippenham – on the line to Bristol

- Kemble – on the line to Stroud

- Swindon – on the line to London Paddington

The town's bus network is run by Coachstyle, who run a town service in addition to regular services to and from Swindon, Yate, Chippenham and Cirencester.

Education

Malmesbury has two primary schools, Malmesbury Church of England Primary School and St. Joseph's Catholic Primary School, and one secondary school, Malmesbury School. St. Joseph's is located in the centre of the town; the Secondary and the other Primary are both on the outskirts.

Twin towns – sister cities

Notable people

For a full list, see: Category:People from Malmesbury

- King Athelstan – first king of all England

- Eilmer of Malmesbury – Benedictine monk best known for his early attempt at a gliding flight using wings

- Saint Aldhelm – Saxon scholar, bishop, poet, musician; patron saint of Wessex and the abbey's first abbot

- Ellie Harrison Tv Presenter,lives in the town

- Thomas Hobbes – prominent British philosopher

- William of Malmesbury – historian

- Hannah Twynnoy – barmaid; reputedly the first person killed by a tiger in Britain

- James Constable – footballer.

- James Scott Douglas – racing driver and the 6th Baronet Douglas

- Roger Scruton – philosopher.

Notes

- 1 2 2011 Census

- ↑ "Water Levels at Malmesbury Abbey". Max Woosnam. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "The Archaeology of Wiltshire"s Towns. An Extensive Urban Survey: MALMESBURY" (PDF). Wiltshire County Archaeology Service. August 2004. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ↑ Yorke, B. A. E. (2014). "Malmesbury". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- ↑ Foot, Sarah (2004). "Æthelstan [Athelstan] (893/4–939), king of England". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/833. Retrieved 26 September 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ http://visionofbritain.org.uk/place/12137

- ↑ Plummer's edition of Bede, Oxford 1896, 1969, mentions Bede's Maildufi urbs in the extensive notes, II 209

- 1 2 3 4 "Malmesbury". BBC History Unit. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ Malmesbury Abbey – Grade I architectural listing – Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1269316)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ Photograph of area at geograph.org.uk

- ↑ R.B. Pugh, Elizabeth Crittall (editors) (1956). "House of Benedictine monks: Abbey of Malmesbury". A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 3. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ eilmer.co.uk Local newsletters as per the other tributes to the birds in the town.

- ↑ "Malmesbury". Malmesbury Town Council. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ "Malmesbury | Unitary council on Thursday 4 May 2017". Wiltshire Council. 5 May 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ "Malmesbury and District Twinning Association Newsletter" (PDF). April 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- 1 2 Baggs, A.P.; Freeman, Jane; Stevenson, Janet H, eds. (1991). "Victoria County History: Wiltshire: Vol 14 pp127-168 – Parishes: Malmesbury". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ↑ Ruth Scurr (2015). John Aubrey: My Own Life. Chatto & Windus. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7011-7907-6.

- ↑ Baggs, A.P.; Freeman, Jane; Stevenson, Janet H, eds. (1991). "Victoria County History: Wiltshire: Vol 14 pp229-240 – Parishes: Westport". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ↑ Population from 1801 until 1961 from Vision of Britain Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ Browning, B (2005). EKCO's of Cowbridge: House and War Factory. Cowbridge Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9551842-0-8.

- ↑ "Uhlsport Hellenic Football League | Club Details | Malmesbury Victoria". Hellenicleague.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ↑ Malmesbury Cricket Club

- ↑ More communities chosen to try out new planning powers http://www.communities.gov.uk/news/corporate/1975278

- ↑ COMING UP TO OUR 70TH DCLG-FUNDED SESSION! http://www.princes-foundation.org/content/coming-our-70th-dclg-funded-session

- ↑ Can David Cameron save England’s oldest town? https://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/hands-off-our-land/9133657/Can-David-Cameron-save-Englands-oldest-town.html

- ↑ "Listed Buildings in Malmesbury, Wiltshire". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "Abbey Church of St Mary and St Aldhelm (1269316)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (revision) (1975) [1963]. Wiltshire. The Buildings of England (2nd ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 321–326. ISBN 0-14-0710-26-4.

- ↑ Toulmin Smith, Lucy, ed. (1907). The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535–1543. 1. London: George Bell. p. 132.

- ↑ Historic England. "The Cross, Market Cross, Malmesbury (Grade I) (1269291)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ↑ "Top 15 unusual buildings for sale". Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Historic England. "St Paul's bell tower (1269428)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "Abbey House and attached rear wall (1269325)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "The Old Bell Hotel and attached front area walls and railings (1269521)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Pugh, R.B.; Crittall, Elizabeth, eds. (1956). "Victoria County History: Wiltshire: Vol 3 pp 340-341 - Hospitals: St John the Baptist, Malmesbury". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "Court House to rear of No.27 and attached wall (1269247)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "St John's Court Nos. 1, 2 and 3 (1269276)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1269271)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ↑ Fenton M.(1990), The Malmesbury Branch Wild Swan Publications Ltd ISBN 0-906867-88-6

- ↑ The inscription reads: Memorand that whereas King Athelstan did give unto the Free School within this borough of Malmesbury ten pounds and to the poor people my almshouse at St John's, ten pounds to be paid yearly by the Aldermen and [[Burgess (title)|Burgess]]es of the same borough for ever. That now Michael Wickes Esquire, late of this said borough and now citizen of London hath augmented and added to the aforesaid gift, viz. to the said Free School ten pounds and to the said almshouse, ten pounds only be paid yearly at St. John's aforesaid within this said borough and by his trustees for ever, and hath also given to the minister of this town for the time being 20s. only by the year for life to preach a sermon yearly on the 19th day of July and to his said trustees 20s. by the year beginning on the 25th day of August. Anno Domini 1694.

References

- John Bowen. The Story of Malmesbury.

External links

- Malmesbury Town Council

- Aerial view of Malmesbury, 1930 – from the English Heritage "Britain from Above" archive

- Historic Malmesbury photos at BBC Wiltshire

- Malmesbury at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Official site of The Warden and Freemen of Malmesbury

- Crowley, D. A. et al, eds. (1991). "A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 14: Malmesbury hundred". Victoria County History. British History Online.

- Malmesbury Town Guide – produced in association with Malmesbury Town Council