Lithium tantalate

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Lithium tantalate | |

| Other names

Lithium Metatantalate | |

| Identifiers | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.584 |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number | WW55470000 |

| Properties | |

| LiTaO3 | |

| Molar mass | 235.887 g/mol |

| Density | 7.46 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 1,650 °C (3,000 °F; 1,920 K) |

| ?/100 ml (25 °C) | |

| Structure | |

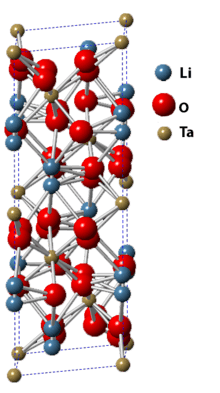

| Space group R3c | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Acute Toxicity: Oral, Inhalation, Dermal |

| Safety data sheet | See: data page http://www.samaterials.com/pdf/Lithium-Tantalate-Wafers-(LiTaO3-Wafers)-sds.pdf |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

LiNbO3 |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

| Wikinews has related news: Tabletop fusion may lead to neutron source |

Lithium tantalate (LiTaO3) is a perovskite which possesses unique optical, piezoelectric and pyroelectric properties which make it valuable for nonlinear optics, passive infrared sensors such as motion detectors, terahertz generation and detection, surface acoustic wave applications, cell phones and possibly pyroelectric nuclear fusion. Considerable information is available from commercial sources about this salt.

Pyroelectric fusion

According to an April 2005 Nature article, Brian Naranjo, Jim Gimzewski and Seth Putterman at UCLA applied a large temperature difference to a lithium tantalate crystal producing a large enough charge to generate and accelerate a beam of deuterium nuclei into a deuteriated target resulting in the production of a small flux of helium-3 and neutrons through nuclear fusion without extreme heat or pressure.[2] Their results have been replicated.

It is unlikely to be useful for electricity generation since the energy required to produce the fusion reactions exceeded the energy produced by them. It is thought that the technique might be useful for small neutron generators, especially if the deuterium beam is replaced by a tritium one. Comparing this with the electrostatic containment of ionic plasma to achieve fusion in a "fusor" or other IEC, this method focuses electrical acceleration to a much smaller non-ionized deuterium target without heat.

Water and freezing

A scientific paper published in February 2010 shows a difference in the temperature and mechanism of freezing water to ice, depending on the charge applied to a surface of pyroelectric LiTaO3 crystals.[3]

References

- ↑ Abrahams, S.C; Bernstein, J.L (1967). "Ferroelectric lithium tantalate—1. Single crystal X-ray diffraction study at 24°C". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 28 (9): 1685. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(67)90142-4.

- ↑ B. Naranjo, J.K. Gimzewski & S. Putterman (2005). "Observation of nuclear fusion driven by a pyroelectric crystal". Nature. 434 (7037): 1115–1117. doi:10.1038/nature03575. PMID 15858570.

- ↑ D. Ehre; E. Lavert; M. Lahav; I. Lubomirsky (2010). "Water Freezes Differently on Positively and Negatively Charged Surfaces of Pyroelectric Materials". Science. 327 (5966): 672–675. doi:10.1126/science.1178085. PMID 20133568.

Further reading

- "Fusion seen in table-top experiment" Physics Web, 27 April 2005