List of destroyed heritage

This is a list of cultural-heritage sites that have been damaged or destroyed accidentally, deliberately, or by a natural disaster, sorted by country.

Cultural heritage can be subdivided into two main types—tangible and intangible heritage. The former includes built heritage such as religious buildings, museums, monuments, and archaeological sites, as well as movable heritage such as works of art and manuscripts. Intangible cultural heritage includes customs, music, fashion and other traditions within a particular culture.[1][2] This article mainly deals with the destruction of built heritage; the destruction of movable collectable heritage is dealt with in art destruction, whilst the destruction of movable industrial heritage remains almost totally ignored.

Deliberate and systematic destruction of cultural heritage, such as that carried out by ISIL, is regarded as a form of cultural genocide.[3][4]

Afghanistan

- During the Soviet invasion, large-scale looting occurred in various archaeological sites including Hadda, ancient site of Ai-Khanoum, the Buddhist monastery complex in Tepe Shortor which dates back to the 2nd century CE, and the National Kabul Museum. These sites were ransacked by various pillagers, including the pro-Russian government forces, destitute villagers, and the local crime rings. The National Museum of Afghanistan suffered the greatest damage, in which the systematic looting has plundered the museum collection and the adjacent Archaeological Institute. As a result, more than two thirds of one hundred thousand pieces of museum treasures and artifacts were lost or destroyed.[5]

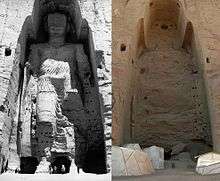

- A pair of 6th-century monumental statues known as the Buddhas of Bamiyan were dynamited by the Taliban in 2001, who had declared them heretical idols.

Argentina

.jpg)

- Several buildings in Buenos Aires were demolished over years, including Pabellón Argentino, Grand Hotel, Ortiz Basualdo Palace, Unzué Palace, Odeón Theater, Coliseo Theater and various palaces in Avenida Alvear.

- Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires was destroyed by a terrorist attack in 1992.

- As response to the Bombing of Plaza de Mayo in 1955 several churches in Buenos Aires were burned and looted, including Santo Domingo convent, St. Ignatius Church, Basilica of San Francesco, St. Michael's Church and Basilica of Saint Nicholas of Bari.

- Old buildings in the city of San Juan were destroyed by an earthquake in 1944, including the Cathedral and the Government House.

- The 1773 Marquez Bridge over the Reconquista River was renewed in 1964 and declared a National Historic Monument of Argentina. In 1997, the Company Autopistas del Oeste demolished it.[6]

Armenia

- Hundreds of mosques in the Armenian region were destroyed during the late 19th-century and the early 20th-century. In 1870, a report by the Viceroyalty of the Caucasus recorded 269 Shia mosques in the region.[7]

- Due to the Anti-Azerbaijani sentiment in Armenia, a mosque in Yerevan was pulled down with a bulldozer in 1990.[8][9] Today there is only one mosque remaining in the city. The destruction is considered facilitated by the systematic erasure of Azeri names from the history of the city.[10]

- Ilham Aliyev, the president of Azerbaijan, accused Armenia of conducting ethnic cleansing policy in Nagorno-Karabakh which was accompanied by the destruction of hundreds of houses, mosques and the entire village.[11] However, critics point out that there is no evidence for this.[12]

Azerbaijan

- Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Azerbaijani authorities in the formerly-Armenian region of Nakhichevan eradicated the region's medieval Christian heritage. An estimated number of 218 medieval churches and 4,500 cross-stones were destroyed, with the final act of the destruction campaign taking place in December 2005 at Djulfa.[13] Azerbaijan's government denies that Christian monuments ever existed in Nakhichevan.[14]

Bahrain

- At least 43 Shia mosques, including the ornate 400-year-old Amir Mohammed Braighi mosque, and many other religious structures were destroyed by the Bahraini government during the Bahraini uprising of 2011.

Belgium

- The Palace of Coudenberg in Brussels burned down in 1731 and its ruins were demolished half a century later.

- Many churches and abbeys were demolished during the French occupation, amongst them the St. Lambert's Cathedral in Liège, the St. Donatian's Cathedral and Eekhout Abbey in Bruges, Florennes Abbey in Florennes, and St. Michael's Abbey in Antwerp.

- The Herkenrode Abbey in Hasselt survived the French Revolution, but subsequently fell into disrepair. In 1826 a fire destroyed much of the church, and the remaining ruins were demolished in 1844.

- On 25 August 1914, the university library of Leuven was destroyed by the Germans. 230,000 volumes were lost, including medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and more than 1,000 incunabula. After the war, a new library was built. During World War II, the new building was again set on fire and nearly a million books were lost.

- During World War I, the city of Ypres was completely destroyed, including its Town Hall and Cloth Hall. These monuments were later rebuilt.

- The Maison du Peuple in Brussels, one of the largest works of architect Victor Horta, was demolished in 1965 to make way for an office building. The surviving buildings designed by Horta were declared UNESCO World Heritage in 2000.

Belize

- Several Maya sites such as San Estevan and Nohmul have been partly demolished.[15]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Through the course of the Bosnian War, countless of cultural heritages belonging to different religious groups were destroyed. Muslim heritage sites suffered the most, with 277 mosques and several other religious facilities, schools and institutions were destroyed by the authorities of the Republic of Srpska as a part of the ethnic cleansing campaign against the local Muslim populations. The most well-known among them include Mehmed Pasha Kukavica Mosque, Arnaudija Mosque, and Ferhat Pasha Mosque. Substantial number of the mosques date back to the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian era. Roman Catholic sites also suffered with more than 50 churches being destroyed, which was associated with the killings of Bosnian Croats by the Bosnian Serbs.[16]

- Parts of the old city of Mostar, including the Stari Most, were destroyed during the Bosnian War. The Stari Most has been rebuilt.

Brazil

- On 8 July 1978, the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro was destroyed by fire.

- On 17 May 2010, the natural history collection of the Instituto Butantan were destroyed by fire.

- On 2 September 2018, the National Museum of Brazil was destroyed by fire.

Canada

- On the night of April 25, 1849, the Canadian Parliament buildings in Montreal were set ablaze by Loyalist rioters. The resulting fire consumed the Parliament's two libraries, parts of the archives of Upper Canada and Lower Canada, as well as more recent public documents. Over 23,000 volumes, forming the collections of the two parliamentary libraries, were lost.

Central America

- The Maya codices were destroyed by Spanish priest Diego de Landa.

China

- Historical Famen Temple went through several times of destructions. Erected first during the Eastern Han dynasty (25—220), it was first destroyed during the years of the Northern Zhou dynasty (557—581). After being rebuilt, it was destroyed again by the earthquake during the Longqing's years (1567–1572) of the Ming dynasty. After another reconstruction, it was destroyed again during the Cultural Revolution. Present construction was completed in 1987.

- An Lushan Rebellion (755—763) which lasted for around 7 years, had devastated the city of Chang'an, a historical capital of several ancient Chinese empires. The city was sacked and occupied several times by the rebels who looted and demolished the buildings, whose materials were reused to build the subsequent capital city of Luoyang. Chang'an never recovered after this obliteration, and it was followed by the decline of the Tang dynasty.

- During the systematic persecution of Buddhists in 845 CE by the Taoist Emperor Wuzong of Tang, more than 4,600 Buddhist temples were destroyed empirewide.[17]

- In 955, Emperor Shizong of the Later Zhou ordered the systematic destruction of Buddha statues due to the need of copper to mint coins. The ordinance had led to the destruction of 3,336 of China's 6,030 Buddhist temples.[18]

- In 1739, the Pagoda of Chengtian Temple was destroyed after a large earthquake hitting the city of Yinchuan. The pagoda was subsequently restored in 1820.

- Porcelain Tower of Nanjing which dates back to the 15th century, was destroyed during the course of the Taiping Rebellion (1850—1864). A modern life size replica was built in 2015.

- In 1860, much of the Old Summer Palace, a Qing-era imperial palace, was set fire, and systematically looted and plundered by the British and French forces. Some of the looted materials including the 3,600 year old treasures. The palace was later sacked again and completely destroyed by the Eight-Nation Alliance when they invaded Beijing.

- Beijing city fortifications which date back to the 15th—16th century were destroyed through the course of the decline of the Qing dynasty in the late-19th century to the early 20th-century. It was severely damaged during the Boxer Rebellion (1898–1901) with the gate towers and watchtowers destroyed, and the British troops tearing down much of the outer city walls. After the collapse of the Qing, the fortifications were gradually dismantled due to variety of reasons. Today, nothing of the Outer City remains intact.

- During the early 20th century, around 1921 Buddhist murals at the Mogao Caves were damaged and vandalized by White Russian exiles.[19]

- Buddhist murals at the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves were damaged by local Muslim population. The eyes and mouths in particular were often gouged out. Pieces of murals were also broken off for use as fertilizer by the locals.[20][21]

- During the Kumul Rebellion in Xinjiang in the 1930s, Buddhist murals were vandalized by Muslims.[22]

- Yongdingmen, the former front gate of the outer city wall of the Beijing city fortifications which dates back to 1553, was demolished in 1950s to make way for the new road system. It was rebuilt in 2005.

- Gate of China in Beijing was demolished by the Chinese government in 1954 in order to make way for the expansion of Tiananmen Square.

- A shrine dedicated to Wei Yan was destroyed by the Chinese government in 1968. A stone tablet which contained the record of his presence was lost after the demolition. The shrine was rebuilt in 1995.[23]

- During the Cultural Revolution, many artifacts, monuments, and buildings belonging to the Four Olds were attacked and destroyed.

- White Horse Temple, Luoyang. Oldest Buddhist temple in China. Some historical artifacts are still missing.[24]

- Famen Buddhist Temple, Shaanxi

- Tomb and remains of Ming Emperor Wanli and empresses[25]

- According to the anthropologist Robert E. Murowchick, a quarter million tombs have been raided since 1990s to rob the antiquities which lay beneath them. Murowchick points out that growing demand for antiquities from both domestic and international markets have encouraged the tomb raiding in China.[26]

- China's aggressive development has resulted in the destruction of more than 30,000 items listed by the state administration of cultural heritage, compiled from various archaeological and historic sites. One conservation campaigner tells that the rate of destruction is worse than during the Cultural Revolution. Destroyed heritage sites include the old town in Dinghai, the old town of Laoximen in Shanghai,[27] a centuries-old market street in Qianmen, and a section of the Great Wall of China.[28] Historical neighborhoods of Beijing and Nanjing were also razed.[29][30]

- The construction of the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River caused water levels to rise, destroying entire cities as well as many historical locations along the river. [31]

- In 2016, the Chinese government ordered the demolition of historical housings in the Larung Gar Tibetan Buddhist institution.[32]

- In 2016, the Chinese government has destroyed around 5,000 mosques in the Muslim-majority Xinjiang region, including the 70% of mosques in the township of Lenger, over the three months of campaign. It was conducted under the guise of public safety, although the locals deem it as a part of the systematic effort to subjugate the Uyghur populations who have been advocating for the independence of East Turkestan State.[33]

Croatia

- 450 churches and monasteries of the Serbian Orthodox Church were destroyed or damaged during the World War II by the Croatian Ustaše, specially in the regions of Dalmatia, Lika, Kordun, Banija and Slavonia.[34]

- War damage of the Croatian War (1991–95) has been assessed on 2271 protected cultural monuments, with the damage cost being estimated at 407 million DM.[35] The largest numbers – 683 damaged cultural monuments – are located in the area of Dubrovnik and Neretva County. Most are situated in Dubrovnik itself.[36] The entire buildings and possessions of 481 Roman Catholic churches, several synagogues and several Serbian Orthodox churches were badly damaged or completely destroyed. Valuable inventories were looted from over 100 churches. The most drastic example of destruction of cultural monuments, art objects and artefacts took place in Vukovar. After the occupation of the devastated city by the Yugoslav Army and Serbian paramilitary forces, portable cultural property were removed from their shelters and museums in Vukovar to the museums and archives in Serbia.[35]

- Church of St. Nicholas, Karlovac, destroyed between 1991 and 1993. Renovated in 2007.

- Dragović monastery, Vrlika, destroyed in 1995. Reestablished in 2004.

- From the period of 1990-2010, approximately 3 million books written in the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet were destroyed in a campaign of bibliocide across Croatia. Anti-Serbian sentiment was at the heart of bibliocide in Croatia and peaked in late 2013 when mobs of protestors began destroying public signs written in the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet.

Czech Republic

- The Old Town Hall in Prague was severely damaged by fire during the Prague uprising of 1945. The chamber where George of Poděbrady was elected King of Bohemia was devastated; the town hall's bell, the oldest in Bohemia, dating from 1313, was melted; and the city archives, comprising 70,000 volumes, as well as historically priceless manuscripts, were completely destroyed.[37]

Denmark

- Copenhagen Fire of 1728, where a great part of medieval Copenhagen vanished.

- Christiansborg Palace, main residence of the Danish Kings, destroyed by fire in 1794.

- Hirschholm Palace, summer residence of the Danish Kings, demolished in 1809–1813 after it stood empty after its role in the affair between Johann Friedrich Struensee and Queen Caroline Matilda of Great Britain in the 1770s.

Egypt

- In the late 12th century, Sultan Al-Aziz Uthman demolished part of the Pyramid of Menkaure.

- The Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was damaged by earthquakes in the 10th and 14th centuries, before being demolished in 1480 to make way for the Citadel of Qaitbay. Some stones from the lighthouse were used in the construction of the citadel, and some other remains have survived underwater.

- Villa Aghion, Alexandria.[38]

- Objects stolen from the Mosque of Taghribirdi and Al-Rifai Mosque.[39]

France

- During the Siege of Strasbourg that took place at the height of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, the total destruction by shelling and fire of the municipal library and the municipal art and archaeology collections resulted in the loss of 400,000 books[40] among which 3,446[41] Medieval manuscripts and thousands of incunables as well as of hundreds of paintings, stained glass windows and archaeological artefacts. The most famous lost object was the original manuscript of the Hortus deliciarum.

- On 23 May 1871, the Tuileries Palace, which had been the usual Parisian residence of French monarchs, was almost entirely gutted in a fire set by members of the Paris Commune, leaving only the stone shell. It was subsequently demolished in 1883.

- The 1978 Palace of Versailles bombing severely damaged parts of the Palace of Versailles, including several priceless pieces of art. The palace was rebuilt and reopened to the public within four years.

Germany

- Myriad historically and architecturally significant buildings were destroyed or severely damaged by World War II and the East German communist regime. Striking examples are palaces like Berlin Palace, Monbijou Palace, or City Palace, Potsdam and churches, such as Dresden Frauenkirche, Berlin Cathedral and Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. Several have been rebuilt since 1990 (including all those mentioned except the Monbijou Palace and the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church).

- The Building housing the Historical Archive of the City of Cologne collapsed on 3 March 2009 during the construction of an underground railway line.

- The Church of St. Lambertus in Immerath was demolished on 9 January 2018 as part of the demolition of the entire village to make way for an expansion of the Garzweiler surface mine.[42] The church had been added to the list of heritage monuments in Erkelenz on 14 May 1985.[43]

Greece

- The Colossus of Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was destroyed in the 226 BC Rhodes earthquake, and its remains were destroyed in the 7th century AD while Rhodes was under Arab rule. In December 2015, a group of European architects announced plans to build a modern Colossus where the original once stood.

- The Statue of Zeus at Olympia, also a Wonder of the Ancient World, was destroyed in around the 5th century CE, although it is not known exactly when or how.

- The Parthenon was extensively damaged in 1687, during the Great Turkish War (1683–1699). The Ottoman Turks fortified the Acropolis of Athens and used the Parthenon as a gunpowder magazine and a shelter for members of the local Turkish community. On 26 September a Venetian mortar round blew up the magazine, and the explosion blew out the building's central portion. About three hundred people were killed in the explosion, which caused fires that burned until the following day and consumed many homes.

Guatemala

- Tikal Temple 33 was destroyed in the 1960s by archaeologists to uncover earlier phases of construction of the pyramid.

Haiti

- Much of Haiti's heritage was damaged or destroyed in the devastating earthquake in 2010, including the National Palace and the Port-au-Prince Cathedral.[44]

Hungary

- Numerous historical buildings in Budapest were damaged or destroyed in World War II, including the Hungarian Parliament Building, the Chain Bridge and the Sándor Palace. These three have now been rebuilt.

India

- A large number of Hindu and other (e.g., Jain) temples were destroyed during the Islamic invasions of India.[45][46] Prominent example includes the Somnath temple in Gujarat. In 1024, during the reign of Bhima I, the prominent Afghan ruler Mahmud of Ghazni raided Gujarat, plundered and destroyed the temple and broke its jyotirlinga.[47][48][49] In 1299, Alauddin Khalji's army under the leadership of Ulugh Khan defeated Karandev II of the Vaghela dynasty, and sacked the (rebuilt) Somnath temple.[50] By 1665, the rebuilt temple was once again ordered destroyed by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.[51] In 1702, he ordered that if Hindus had revived worship there, it should be demolished completely.[52]

- Around 1200 CE, one of the most prominent seats of learning in ancient India, Nalanda university, was sacked and destroyed by Turkish leader Bakhtiyar Khalji.

- In 1565 CE, after the Battle of Talikota, the capital city of Vijayanagara, with all its temples, palaces, mansions and monuments, was sacked and completely destroyed by an invading Muslim army raised by the five Bahamani Sultanates. What remains now are the ruins of Hampi.

- In 1664, Aurangzeb destroyed the Kashi Vishwanath Temple and built the Gyanvapi Mosque over its walls. The remnants of the temple wall can still be seen today, as was depicted in the 19th century sketch by James Prinsep.

Christian missionary Edwin Greaves (1909), of the London Missionary Society, described the site as follows: "At the back of the mosque and in continuation of it are some broken remains of what was probably the old Bishwanath Temple. It must have been a right noble building ; there is nothing finer, in the way of architecture in the whole city, than this scrap. A few pillars inside the mosque appear to be very old also." [53]

- The Bashir Bagh Palace and Dewan Devdi of Hyderabad were destroyed in the years following independence.

- On 6 December 1992, the historical Babari Mosque was destroyed by Hindu extremists.

- On 26 April 2016, the National Museum of Natural History, New Delhi and its valuable collection of animal fossils and stuffed animals was destroyed by fire.[54]

Iraq

- The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, are believed to have been destroyed sometime after the 1st century AD. Their existence is not confirmed by archaeology, and there have been suggestions that the gardens were purely mythical.

- The Round City of Baghdad, the seat of the Abbasid caliph, was sacked by the Mongols led by Hulegu in 1258. Large section of the city as well as irrigation system and the House of Wisdom, a library and intellectual center, were destroyed. The city was attacked again by Tamerlane in 1401, leading to the almost complete destruction.

- Several historical gates of Baghdad dating back to the 12th century were destroyed by the occupying British and Ottoman forces throughout the early-20th century and the World War I.

- Since the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, various archaeological sites and museums have been looted, including the ancient cities of Adab, Hatra and Isin where U.S. military protection was absent. The most prominent among them being the National Museum of Iraq where as much as 170,000 items were looted, including the 5,000 year old statues. In addition, several sites such as Babylon saw the destruction of its archaeology-rich subsoil as a result of military planning.

- During the civil war ensued the 2003 invasion, several historical sites were destroyed by various groups. In 2006 and 2007, Al-Askari Mosque was bombed by Sunni militants twice in the course of two years. In 2006, the Minaret of Anah and the statue of Al-Mansur were bombed by Shia militant and destroyed. All the aforementioned buildings were later reconstructed.

- The Islamic State (IS) has destroyed much of the cultural heritage in the areas it controls in Iraq. At least 28 religious buildings have been looted and destroyed, including Shiite mosques, tombs, shrines and churches.[55] In addition, numerous ancient and medieval sites and artifacts, including the ancient cities of Nimrud and Hatra, parts of the wall of Nineveh, the ruins of Bash Tapia Castle and Dair Mar Elia, and artifacts from the Mosul Museum were also destroyed.

Ireland

- During the Battle of Dublin at the beginning of the Irish Civil War in 1922, munitions were stored at the Four Courts building, which housed 1,000 years of Irish records in the Public Record Office. Under circumstances that are disputed, the munitions were exploded, destroying much of Ireland's historical record.

Israel

- Following the conquest of the Old City of Jerusalem by the Arab Legion in 1948, under the Jordanian annexation, Jewish sites were systematically damaged and destroyed. In particular, all but one of the thirty-five synagogues of the Jewish Quarter were destroyed.[56]

- The Aleppo Codex, the authoritative Hebrew bible text, was partially destroyed during anti-Jewish riots in Syria in 1948.

Italy

- Various historic buildings were demolished in the 19th and 20th centuries to make way for railways, industrial areas or other modern buildings. Examples include the Castello di Villagonia and the Real Cittadella in Sicily.

- The monastery of Monte Cassino was destroyed during the Battle of Monte Cassino in World War II, but it was rebuilt after the war.

- Several churches and other heritage sites were damaged or destroyed during earthquakes such as the 1997 Umbria and Marche earthquake, the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake and the August 2016 Central Italy earthquake.

Japan

- Shuri Castle, a palace of the Ryukyu Kingdom first built in the 14th century, was destroyed during the Battle of Okinawa in World War II. The Japanese forces had set up a defense perimeter which goes through the underground of the castle. U.S. military targeted this location by shelling with the battleship USS Mississippi (BB-41) for three days in May 1945. The castle burned down subsequently after. It was later reconstructed in the 1990s.

- Kinkaku-ji (Golden Pavilion) of Kyoto, Japan was burnt down by an arsonist in 1950, but was restored in 1955.[57]

Kosovo

Numerous Albanian cultural sites in Kosovo were destroyed during the Kosovo conflict (1998–1999) which constituted a war crime violating the Hague and Geneva Conventions.[58] In all 225 out of 600 mosques in Kosovo were damaged, vandalised, or destroyed alongside other Islamic architecture and Islamic libraries and archives with records spanning 500 years.[59][60] Additionally 500 Albanian owned kulla dwellings (traditional stone tower houses) and three out of four well preserved Ottoman period urban centres located in Kosovo cities were badly damaged resulting in great loss of traditional architecture.[61][62] Kosovo's public libraries, in particular 65 out of 183 were completely destroyed with a loss of 900,588 volumes. [63] [64][63] During the war, Islamic architectural heritage posed for Yugoslav Serb paramilitary and military forces as Albanian patrimony with destruction of non-Serbian architectural heritage being a methodical and planned component of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo.[62][65]

NATO bombing in March–June 1999 resulted in some accidental damages to churches and a mosque. Revenge attacks against Serbian religious sites commenced following the conflict and the return of hundreds of thousands of Kosovo Albanian refugees to their homes.[66] According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, several Serbian cultural objects, including 155 Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries, were destroyed by Kosovo Albanians between June 1999 and March 2004.[67]

Libya

- During the civil war of 2011, various sites were vandalized, looted or destroyed.[68]

- In March 2015, during the second civil war, the Islamic State destroyed Sufi shrines near Tripoli.[69]

Malaysia

- Candi Number 11 also known as Candi Sungai Batu Estate, a 1,200 year old ruin of a tomb-temple located in the Bujang Valley historical complex in Kedah was demolished in 2013 by housing developers who claimed not to have known the historical significance of the stone edifice.[70]

Maldives

- The destruction of the Buddhist artifacts by Islamists took place in the aftermath of the coup in which Mohamed Nasheed was toppled as President.[71] Islamist politicians entered the government which succeeded Nasheed.[72][73] On 7 February 2012,[74] The National Museum was stormed by Islamists who destroyed the Buddhist artifacts.[75][76][77][78] Most of Maldive's Buddhist physical history was obliterated.[79][80] Hindu artifacts were also targeted for obliteration and the actions have been compared to the attacks on the Buddhas by the Taliban.[81][82][83][84][85][86]

Mali

- Parts of the World Heritage Site of Timbuktu were destroyed after the Battle of Gao in 2012, despite condemnation by UNESCO, the OIC, Mali, and France.

Malta

- A number of buildings of historical or architectural importance which had been included on the Antiquities List[87] were destroyed by aerial bombardment during World War II, including Auberge d'Auvergne, Auberge de France and the Slaves' Prison in Valletta,[88] the Clock Tower,[89] Auberge d'Allemagne[90] and Auberge d'Italie[91] in Birgu, and two out of three megalithic temples at Kordin.[92][93] Others such as Fort Manoel also suffered severe damage, but were rebuilt after the war.[94]

- Other buildings which were not included on the Antiquities List but which had significant cultural importance were also destroyed during the war. The most notable of these was the Royal Opera House in Valletta, which is considered as "one of the major architectural and cultural projects undertaken by the British" by the Superintendence of Cultural Heritage.[95]

- The Gourgion Tower in Xewkija, which was included on the Antiquities List, was demolished by American forces in 1943 to make way for an airfield. Many of its inscriptions and decorated stones were retrieved and they are now in storage at Heritage Malta.[96]

- Palazzo Fremaux, a building included on the Antiquities List and which was scheduled as a Grade 2 property, was gradually demolished between 1990 and 2003. The demolition was condemned by local residents, the local government and non-governmental organizations.[97][98]

- Azure Window , was a 28-metre-tall (92 ft) limestone natural arch on the island of Gozo in Malta. It was located in Dwejra Bay in the limits of San Lawrenz, close to the Inland Sea and the Fungus Rock. It was one of Malta's major tourist attractions. The arch, together with other natural features in the area of Dwejra, is featured in a number of international films and other media representations. The formation was anchored on the east end by the seaside cliff, arching over open water, to be anchored to a free standing pillar in the sea to the west of the cliff. It was created when two limestone sea caves collapsed. Following years of natural erosion causing parts of the arch to fall into the sea, the arch and free standing pillar collapsed completely during a storm on March 2017.

- Villa St Ignatius, a 19th-century villa with historical and architectural significance,[99] was partially demolished in late 2017. This was condemned by numerous non-governmental organizations and other entities.[100]

Myanmar

- Shwedagon Paya temple complex in Yangon, built 2500 years ago, was severely damaged after Cyclone Nargis passing the region in 2008, which caused the worst natural disaster in the recorded history of Myanmar.[101]

Nepal

- The 7.8 Mw Nepal earthquake in 2015 demolished the heritage Dharahara situated in Kathmandu which was a main tourist attraction in Nepal. It also destroyed centuries old temples in the Kathmandu, Bhaktapur and Patan Durbar Squares.[102][103]

New Zealand

- ChristChurch Cathedral, completed in 1904, was damaged several times by the repeated earthquakes in 1881, 1888, 1901, 1922, and September 2010. The building was severely damaged after the 2011 Christchurch earthquake, and subsequently demolished.

Norway

- From 1992 to 1995 members of the Norwegian black metal scene began a wave of arson attacks on old medieval Christian churches. By 1996, there had been at least 50 attacks and destructions on heritages in Norway.

Pakistan

- Archaeological site of Harappa which dates back to 2600 BCE was heavily damaged during the British rule in 1857. Bricks from the ruins were brought out and used as track ballast during the construction of Lahore—Multan railway line.[104] Since the discovery, the site was constantly being damaged by the local farmers in the process of turning it into an agriculture land.[105]

- Shaheed Ganj Mosque in Lahore was demolished by the Sikhs in 1935. Sikhs had been occupying the public square near the mosque since the capture of Lahore by Bhangi Misl in the 18th century. The conflict concerning the mosque had heightened during the British colonial occupation era, as Muslims were not allowed to pray there. The demolishing of the mosque had led to the Muslims protesters holding marches toward the mosque, which was dispersed by the police opening fire on them.[106]

- Looters and the Taliban destroyed much of Pakistan's Buddhist artifacts left over from the Buddhist Gandhara civilization especially in Swat Valley.[107] Gandhara Buddhist relics were deliberately targeted by the Taliban for destruction,[108] and illegally looted by smugglers.[109] Kushan era Buddhist stupas and statues in Swat valley, including the Jehanabad Buddha's face, were demolished by the Taliban.[110][111][112][113] The government was criticized for doing nothing to safeguard the statue after the initial attempt at destroying the Buddha, which did not cause permanent harm, and when the second attack took place on the statue the feet, shoulders, and face were demolished.[114] A rehabilitation attempt on the Buddha was made by Luca Olivieri and a group from Italy.[115][116]

Philippines

.jpg)

World War II

The resulting carnage and the aftermath of the Battle of Manila (followed by the Manila massacre) is responsible for the near total obliteration and evisceration of irreplaceable cultural, and historical heritage & treasures of the "Pearl of the Orient" (an international melting pot and a living monument of the meeting and confluence of Spanish, American and Asian cultures). Countless government buildings, universities and colleges, convents, monasteries and churches, and their accompanying treasures, all dating back to the 16th century and in a variety of style, were wiped out and ruined by both Japanese and inadvertently the American forces battling for the control of the city.

The most devastating damage happened at the ancient walled city of Intramuros, as a result of the assault from 23–26 February, until its total liberation on 4 March, Intramuros was a shell of its former glory (except the church of San Agustin, the sole survivor of the carnage). Outside the walls, large areas of the city had been levelled.

After the Liberation, as part of rebuilding Manila, most of the buildings damaged during the war were either demolished in the name of "Progress", or rebuilt in a manner that bears no resemblance to the original; replacing European architectural styles during the Spanish and early American era with modern American- and imitation-style architecture. Only a few surviving old buildings remain intact, though even those that remain are continuously endangered to deterioration & neglect, political mismanagement brought on by graft and corruption, rapid urbanization & economic redevelopment, low public awareness & ignorance.

2013 Bohol earthquake

Several historic buildings were damaged or destroyed during the 2013 Bohol earthquake, including the Loboc Church, the Loon Church, the Maribojoc Church and the Baclayon Church.

Poland

- Warsaw Old Town including the Royal Castle, Warsaw, Warsaw New Town, Łazienki Park including the Łazienki Palace, Ujazdowski Castle destroyed by Nazi Germany in 1944. Rebuilt from the 1950s to 1980s.

Romania

- The 60 m-high tower of Rotbav fortified church, dating back to the 13th century, collapsed on 20 February 2016.[117][118]

- Many historical buildings were demolished to construct the Centrul Civic in Bucharest.

Russia

- During February–March 1944, the Soviet conducted the expulsion of the Chechens and Ingush from the North Caucasus as a part of the Soviet forced settlement program of the non-Russian ethnic minorities. The operation was resulted in the deportation of 496,000 Chechens and Ingush populations, and the death of around quarter of them. It was also accompanied by the destruction of local cultural and societal heritages; names of these nations were erased from the books and records; placenames were replaced with Russian ones; mosques were demolished; villages were razed; and the historical Nakh language manuscripts were almost completely destroyed.

- Around 191,000 Crimean Tatars faced the deportation by the Soviets in May 1944. This was accompanied by virtual "ethnic cleansing" from the Crimea, with all the Tatar placenames being replaced with Russian ones, and the Muslim graveyards and religious objects were destroyed or converted into secular places.

- With the change in values imposed by communist ideology, the tradition of preservation was broken. Independent preservation societies, even those that defended only secular landmarks such as Moscow-based OIRU were disbanded by the end of the 1920s. A new anti-religious campaign, launched in 1929, coincided with collectivization of peasants; destruction of churches in the cities peaked around 1932. A number of churches were demolished, including the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow and St. Michael's Cathedral in Izhevsk. Both of these were rebuilt in the 1990s and 2000s.

- In 1959 Nikita Khrushchev launched his anti-religious campaign. By 1964 over 10 thousand churches out of 20 thousand were shut down (mostly in rural areas) and many were demolished. Of 58 monasteries and convents operating in 1959, only sixteen remained by 1964; of Moscow's fifty churches operating in 1959, thirty were closed and six demolished.

- In Moscow alone losses of 1917–2006 are estimated at over 640 notable buildings (including 150 to 200 listed buildings, out of a total inventory of 3,500) – some disappeared completely, others were replaced with concrete replicas.

- 'Mephistopheles', figure on a St Petersburg building on Lakhtinksaya Street known as the House with Mephistopheles, smashed by a fundamentalist Orthodox group in 2015.[120][121][122]

Saudi Arabia

- Various mosques and other historic sites, especially those relating to early Islam, have been destroyed in Saudi Arabia. Apart from early Islamic sites, other buildings such as the Ajyad Fortress were also destroyed.

Singapore

- The Singapore Stone was blown up in 1843 to make way for Fort Fullerton.

Slovenia

- Partisan forces or their successors destroyed approximately 100[123] castles and manors during and after the Second World War.[124] Examples include Ajman Manor, Belnek Castle, Boštanj Castle, Brdo Castle, Čušperk Castle, Dol Mansion, Dolena Castle, Gracar Castle, Haasberg Castle, Klevevž Castle, Kolovec Castle, Križ Castle, Krupa Castle, Mokronog Castle, Pogonik Castle, Radelstein Castle, Soteska Castle, Špitalič Manor, Turn Castle, and Volčji Potok Manor.

- An Allied raid heavily damaged Žužemberk Castle during the Second World War.

- Partisan forces or their successors destroyed many churches during and after the Second World War. Examples include the churches in Ajbelj, Gabrje, Hinje, Koče, Kočevska Reka, Morava, Plešivica, Srobotnik pri Velikih Laščah, Stari Log, Trava, Velika Račna, Zafara, and Žužemberk.

- A German raid during the Second World War destroyed the church in Dragatuš.

- Allied raids destroyed churches during the Second World War. Examples include the church in Dvor and Sts. Peter and Paul Church in Ptuj.

South Korea

- Hwangnyongsa, a massive Buddhist temple in Gyeongju which dates back to the 7th century, was burned down by the Mongolians during their invasion in 1238.

- Hundreds of Buddhist monasteries were shut down or destroyed during the Joseon period as a part of anti-Buddhism policy. In 1407, during the reign of Taejong, the regulations were imposed on the number of Buddhist temples which limited to 88.[125] Sejong the Great further reduced the number to 36.[126][125] Many Buddhist statues were also destroyed during the reign of Jungjong (1506—1544).

Spain

- Because of the Ecclesiastical confiscations of Mendizábal, secularization of church properties in 1835–1836, several hundreds of church buildings, monasteries, etc., or civil buildings owned by the Church were partly or totally demolished. Many of the art works, libraries and archives contained were lost or pillaged in the time the buildings were abandoned and without owners. Among them were important buildings as Santa Caterina convent (the first gothic building in Iberian Peninsula) and Sant Francesc convent (gothic too, one of the richest in the country), both in Barcelona, or San Pedro de Arlanza Roman monastery, near Burgos, now ruined.

- Several monuments demolished in Calatayud: the church of Convent of Dominicos of San Pedro Mártir (1856), Convent of Trinidad (1856), Church of Santiago (1863), Church of San Torcuato and Santa Lucía (1869) and Church of San Miguel (1871).[127]

- In Zaragoza were demolished part of the Palace of La Aljafería (1862) and Torre Nueva (1892).[127]

- Churches, monasteries, convents and libraries were destroyed during the Spanish Civil War.[128]

- A Virxe da Barca sanctuary, located in Muxia, was destroyed by lightning.[129]

Sri Lanka

- The Palace of King Parakramabahu I of Polonnaruwa was set into fire by the Kalinga Magha lead Indian invaders in the 11th century. The ruins and the effect of the fire is still visible.[130]

- The Library of Jaffna was burned in 1981, which had over 97,000 manuscripts in 1981 as a part of Sri Lankan war.

Sweden

- Tre Kronor, main residence of the Swedish Kings, destroyed by fire in 1697. Several important documents of the history of Sweden were lost in the fire.

Syria

- Much of Syria's cultural heritage was damaged, destroyed or looted during the Syrian Civil War. Destroyed buildings include the minaret of the Great Mosque of Aleppo and the Al-Madina Souq, while others such as Krak des Chevaliers were damaged.[131]

- Khusruwiyah Mosque (Husrev Mosque)[132]

- The Islamic State destroyed the Lion of Al-lāt, the temples of Bel and Baalshamin, the Arch of Triumph and other sites in Palmyra. The group also destroyed the Monastery of St. Elian, the Armenian Genocide Memorial Church, and several ancient sculptures in the city of Raqqa.

- During the Turkish military operation in Afrin at 2018, Turkish shelling had seriously damaged the ancient temple of Ain Dara at Afrin.[133][134]

Turkey

- The Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was destroyed by arson in 356 BC. It was later rebuilt, but it was damaged in a raid by Goths in 268 AD. Its stones were subsequently used in other buildings, including Hagia Sophia and other buildings in Constantinople. A few fragments of the structure still survive in situ.

- The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, another Wonder of the Ancient World, was destroyed by a series of earthquakes between the 12th and 15th centuries. Most of the remaining marble blocks were burnt into lime, but some were used in the construction of Bodrum Castle by the Knights Hospitaller, where they can still be seen today. The only other surviving remains of the mausoleum are some foundations in situ, a few sculptures in the British Museum, and some marble blocks which were used to build a dockyard in Malta's Grand Harbour.

Turkmenistan

Ukraine

- Great Suburb Synagogue, Lviv

United Kingdom

- Several historic structures such as the Euston Arch in London and the Royal Arch in Dundee were demolished in the 1960s to make way for redeveloped infrastructure.

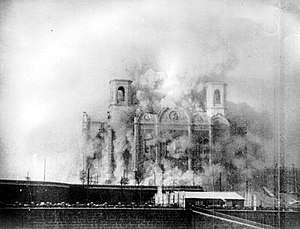

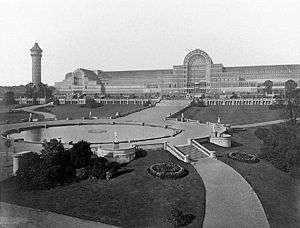

- The Crystal Palace in London was destroyed by fire in 1936.

- St Mary's Church in Reculver, an exemplar of Anglo-Saxon architecture and sculpture, was partially demolished in 1809.

- St Michael's Church in Coventry was a 14th-century cathedral that was nearly destroyed during the Coventry Blitz of 14 November 1940 by the German Luftwaffe. Only the tower, spire, the outer wall and the bronze effigy and tomb of its first bishop, Huyshe Yeatman-Biggs, survived. The ruins of this cathedral remain hallowed ground and are listed at Grade I.[135]

- Charles Church in Plymouth was entirely burned out by incendiary bombs dropped by the Luftwaffe, on the nights of 21 and 22 March 1941. However, it has since been encircled by a roundabout and turned into "a memorial to those citizens of Plymouth who were killed in air-raids on the city in the 1939–45 war."

- Coleshill House, a historic mansion in Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire) was entirely destroyed in a fire in 1952, and many historic items within were lost. The ruins were demolished in 1958.

- Clandon Park House, a historic mansion in Surrey, was severely damaged by fire on 29 April 2015, leaving the house "essentially a shell" and destroying thousands of historic items, including one of the footballs kicked across no-man’s land on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916.[136]

- The Royal Clarence Hotel in Exeter, considered England's oldest hotel, was almost completely destroyed by fire on 28 October 2016.[137]

- The Mackintosh Building of Glasgow School of Art was extensively damaged by fire on 15 June 2018. Alan Dunlop, the school’s professor of architecture, said: “I can’t see any restoration possible for the building itself. It looks totally destroyed.”[138]

United States

- Pennsylvania Station, in New York City, was a Beaux-Arts style "architectural jewel" of New York City. Controversially, the above-ground portions of the station were demolished in 1963, making way for the construction of the Madison Square Garden arena. The controversy energized a historic preservation movement in New York City and the United States.

- Since the 1960 start of the National Historic Landmark (NHL) program and the 1966 start of the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), numerous landmarks designated in those programs have been destroyed. In some cases the destruction was mitigated by documentation of the artifact and/or reproduction.

- Losses by flood and wind damage include:

- The 1855-built NHL Old Blenheim Bridge, the longest surviving covered bridge, was destroyed by Hurricane Irene-related flooding in 2011.

- Numerous NRHP-listed coastal properties in Mississippi and Louisiana, destroyed by Hurricane Katrina

- Losses by fire, arson or otherwise, include:

- Russian-built NHL Fort Ross Chapel, pre-1841, destroyed 1970, subsequently reproduced

- on July 12, 1973, fire destroyed about 80% of the military personnel records held at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, MO. [139]

- Losses by permitted processes include:

- NHL Soldier Field stadium, 1924-built, altered by 2002 renovation

- NHL Edwin H. Armstrong House, demolished 1983

- NHL Army Medical Museum and Library. 1887–1969, demolished

- NHL NASA wind tunnels Eight-Foot High Speed Tunnel (1936–2011) and Full Scale 30- by 60-Foot Tunnel (1936–2010).

- Ships broken up include:

- NHL Wapama (steam schooner) (1915–2013), scrapped, though documented by Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) throughout its dismantling

- NHL President (steamboat) (1924–2009), disassembled

- Losses by flood and wind damage include:

- Other losses of covered bridges, landmarked or not, include:

- Dooley Station Covered Bridge (1917–1960), arson; replaced by move of 1856-built Portland Mills Covered Bridge

- Bridgeton Covered Bridge (1868–2005), arson, since replaced by replica

- NRHP Jeffries Ford Covered Bridge (1915–2002), arson

- Welle Hess Covered Bridge No. S1 (1871–1981), collapsed, partially reproduced off-site

- Whites Bridge (1869–2013), arson

- Babb's Bridge (1864–1973), arson, replaced by replica

- In 2014 a 4,500-year-old Coast Miwok Indian burial ground and village was found near Larkspur, California, and destroyed to make way for a multimillion-dollar housing development.[140]

- Grand Coulee Dam, constructed between 1933 and 1942 on the Columbia River disturbed burial grounds and destroyed ancient villages on 18,000 acres (7,300 ha) of the Colville Indian Reservation, home to a dozen tribes at the time.[141]

Uruguay

- In 1969, an original Flag of the Treinta y Tres from the Cisplatine War was stolen from the history museum. The national symbol was taken on July 16, 1969 by a revolutionary group called OPR-33. The historical flag was last seen in 1975 in Buenos Aires but has been considered missing since the day of its theft. This is still a matter of political debate.[142][143]

Yemen

- According to Nabil Monassar, the vice director of the General Organization for the Preservation of the Historic Cities of Yemen, Yemeni Civil War and Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen had led to the destruction of more than 80 historical sites and monuments, as well as hundreds of individual buildings, including:[144]

- Archaeological site of Ma'rib, including the Great Dam of Marib and Awwam Temple which badly damaged in 2015.[145]

- Old City of Sana'a[146] including the prominent Qubbat al-Mahdi mosque[145]

- Historic Town of Zabid

- Old City of Sa'dah

- Walled City of Shibam

- 12th-century Cairo Castle in Taiz was struck by Saudi-led airstrikes. According to the UN report, 30% of the castle had been damaged.

- Al-Muqah temple and the archaeological site of Sirwah

- Al-Naqrah temple and the archaeological site of Baraqish[145]

- Historic center of Al Jawf Governorate

- Dhamar Regional Museum[147]

See also

References

- ↑ "What is meant by "cultural heritage"?". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Stenning, Stephen (21 August 2015). "Destroying cultural heritage: more than just material damage". British Council. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Porter, Lizzie (23 July 2015). "Destruction of Middle East's heritage is 'cultural genocide'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ Sehmer, Alexander (5 October 2015). "Isis guilty of 'cultural cleansing' across Syria and Iraq, Unesco chief Irina Bokova says". The Independent. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ World Archaeological Congress and Agnew, Neville, and Bridgland, Janet (2006). Neville Agnew; Janet Bridgland, eds. Of the past, for the future: integrating archaeology and conservation: proceedings of the conservation theme at the 5th World Archaeological Congress, Washington, D.C., 22–26 June 2003. Los Angeles, Calif.: Getty Conservation Institute. p. 249.

- ↑ Piotto, Alba (27 June 1997). "Derriban un puente histórico al construir una autopista". Clarín (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Кавказский календарь на 1870 год. Тифлис, типография Главного Управления Наместника Кавказского. 1869. p. 392.

- ↑ Robert Cullen, A Reporter at Large, “Roots,” The New Yorker, April 15, 1991, p. 55

- ↑ Thomas De Waal. Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war. NYU Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7, ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9, p. 79.

- ↑ de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war. New York University Press. p. 80.

That the Armenians could erase an Azerbaijani mosque inside their capital city was made easier by a linguistic sleight of hand: the Azerbaijanis of Armenia can be more easily written out of history because the name “Azeri” or “Azerbaijani” was not in common usage before the twentieth century. In the premodern era these people were generally referred to as “Tartars”, “Turks” or simply “Muslims”. Yet they were neither Persians nor Turks; they were Turkic-speaking Shiite subjects of Safavid dynasty of the Iranian Empire – in other words, the ancestors of people, whom we would now call “Azerbaijanis”. So when the Armenians refer to the “Persian mosque” in Yerevan, the name obscures the fact that most of the worshippers there, when it was built in the 1760s, would have been, in effect, Azerbaijanis.

- ↑ Holding, APA Information Agency, APA. "Ilham Aliyev: Armenia, which destroys mosques, can never be a friend of Muslim states". Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ "Karabakh Mosques Repaired". «Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն» ռադիոկայան. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ "Sacred Stones Silenced in Azerbaijan | History Today". historytoday.com. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ "Tragedy on the Araxes - Archaeology Magazine Archive". archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ Jones, Patrick E.; Stevenson, Mark (13 May 2013). "Mayan Nohmul Pyramid In Belize Destroyed By Bulldozer". Huffington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ Riedlmayer, András J. DESTRUCTION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE IN BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA, 1992–1996:A Post-war Survey of Selected Municipalities. Archnet. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Old Book of Tang 《旧唐书·武宗纪》(卷一八上):“还俗僧尼二十六万五百人,收充两税户”“收奴婢为两税户十五万人”。

- ↑ four imperial persecutions of Buddhism in China

- ↑ 杨秀清 Xiuqing Yang (2006). 风雨敦煌话沧桑: 历经劫难的莫高窟 Feng yu Dunhuang hua cang sang: li jing jie nan de Mogao ku. 五洲传播出版社. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-7-5085-0916-7.

- ↑ Whitfield, Susan (2010). "A place of safekeeping? The vicissitudes of the Bezeklik murals". In Agnew, Neville. Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road: proceedings of the second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China (PDF). Getty Publications. pp. 95–106. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2012.

- ↑ Anna Akasoy; Charles S. F. Burnett; Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim (2011). Islam and Tibet: Interactions Along the Musk Routes. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-7546-6956-2.

- ↑ "Old Sterile Death Leaves Its Mark Over Sinking". LIFE. Time Inc. 15 (24): 99. 13 December 1943. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ↑ "镇远将军魏延祠 [Shrine of General Wei Yan]". 中华魏氏网 [Chinese Wei Family Website] (in Chinese). 5 January 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ↑ Barme, Geremie (2008). The Forbidden City. Harvard University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 0-674-02779-5. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ "China's reluctant Emperor", The New York Times, Sheila Melvin, Sept. 7, 2011.

- ↑ History in Ruins: Cultural Heritage Destruction around the World. The Antiquities Coalition. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Demolition Of Laoximen: Shanghai’s Best Link To Its Pre-Colonial Past May Soon. SupChina. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ China loses thousands of historic sites. The Guardian. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Kaufman, Jonathan. Razing History: The Tragic Story of a Beijing Neighborhood's Destruction. The Atlantic. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Teixeira, Lauren.Why Is Nanjing Demolishing Its Last Historic Neighborhood?. SupChina. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/chinas-three-gorges-dam-disaster/

- ↑ "China is Demolishing the World's Largest Tibetan Buddhist Institution, Displacing Thousands of Monks". nextshark.com. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ Under the Guise of Public Safety, China Demolishes Thousands of Mosques. RFA. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Mileusnić 1997.

- 1 2 Destruction and Conservation of Cultural Property, ed. Robert Layton, Peter G. Stone & Julian Thomas, One World Archeology, Routledge 2001, London, pg. 162. ISBN 0-203-16509-8

- ↑ The destruction by war of the cultural heritage in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina presented by the Committee on Culture and Education, Fact-finding mission of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, Rapporteur: Mr Jacques Baumel, France, RPR, 2 February 1993

- ↑ Svoboda, Alois (1965). Prague. Translated by Finlayson-Samsour, Roberta. Sportovní a Turistické Nakladatelství. p. 21.

- ↑ Schwartzstein, Peter (19 April 2014). "Egypt's Population Boom Threatens Cultural Treasures". National Geographic.

- ↑ Hassan, Khalid (20 January 2017). "How Egypt is trying to stop looting at ancient mosques". Al-Monitor. CAIRO.

- ↑ "La petite histoire d'une grande bibliothèque". mediatheques.strasbourg.eu. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ "BNU Strasbourg - Histoire". bnu.fr. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Rahman, Khaleda (12 January 2018). "19th Century cathedral is razed to the ground by energy company as it begins demolition of an entire German village to make way for coal mining". Daily Mail. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ↑ "St. Lambertus Immerath" (PDF). erkelenz.de (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2018.

- ↑ Haiti Cultural Recovery Project ( Archived 4 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot. Inscribing the Other,Inscribing the Self:Hindu-Muslim Identities in Pre-Colonial India. Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol.37, No.4 (October 1995).

- ↑ S.R. Goel, Hindu Temples what happened to them. Voice of India, 1991. ISBN 81-85990-49-2

- ↑ Yagnik & Sheth 2005, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Thapar 2004, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Meenakshi Jain (21 March 2004). "Review of Romila Thapar's "Somanatha, The Many Voices of a History"". The Pioneer. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ Yagnik & Sheth 2005, p. 47.

- ↑ Satish Chandra, Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals, (Har-Anand, 2009), 278.

- ↑ Yagnik & Sheth 2005, p. 55.

- ↑ Edwin Greaves (1909). Kashi the city illustrious, or Benares. Allahabad: Indian Press. pp. 80–82

- ↑ Vidhi Doshi (26 April 2016). "Fire guts Delhi's natural history museum". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ al-Taie, Khalid (13 February 2015). "Iraq churches, mosques under ISIL attack". Mawtani.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ "Jordan's Desecration of Jerualem (1948-1967)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑

- ↑ Herscher & Riedlmayer 2000, pp. 109–110

- ↑ Herscher 2010, p. 87.

- ↑ Mehmeti, Jeton (2015). "Faith and Politics in Kosovo: The status of Religious Communities in a Secular Country". In Roy, Olivier; Elbasani, Arolda. The Revival of Islam in the Balkans: From Identity to Religiosity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 72. ISBN 9781137517845.

- ↑ Herscher, Andrew; Riedlmayer, András (2000). "Monument and crime: The destruction of historic architecture in Kosovo". Grey Room (1): 111–112. JSTOR 1262553.

- 1 2 Bevan, Robert (2007). The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. Reaktion books. p. 85. ISBN 9781861896384.

- 1 2 Frederiksen, Carsten; Bakken, Frode (2000). Libraries in Kosova/Kosovo: A General Assessment and a Short and Medium-term Development Plan (PDF) (Report). IFLA/FAIFE. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9788798801306.

- ↑ Riedlmayer, András (2007). "Crimes of War, Crimes of Peace: Destruction of Libraries during and after the Balkan Wars of the 1990s". Library Trends. 56 (1): 124.

- ↑ Herscher, Andrew (2010). Violence taking place: The architecture of the Kosovo conflict. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780804769358.

- ↑ András Riedlmayer. "Introduction in Destruction of Islamic Heritage in the Kosovo War, 1998–1999" (PDF). p. 11.

- ↑ Edward Tawil (February 2009). "Property Rights in Kosovo: A Haunting Legacy of a Society in Transition" (PDF). New York: International Center for Transitional Justice. p. 14.

- ↑ Kingsley, Patrick (7 March 2015). "Isis vandalism has Libya fearing for its cultural treasures". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ Thornhill, Ted (10 March 2015). "ISIS continues its desecration of the Middle East: Islamic State reduces Sufi shrines in Libya to rubble in latest act of mindless destruction". Daily Mail. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ Wright, Tom (10 December 2013). "Candi controversy: Bulldozing 1,000 years of history". The Star. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Wright, Tom (11 February 2012). "Islamism Set Stage for Maldives Coup". The Wall Street Journal. MALE, Maldives.

- ↑ Francis, Krishan (12 February 2012). "New President of the Maldives names religious conservatives as part of coalition cabinet". Global News. MALE, Maldives.

- ↑ "New Maldives leader names conservatives to Cabinet". Associated Press. MALE, Maldives. Associated Press. 12 February 2012.

- ↑ "Islamists destroy some 30 Buddhist statues". AsiaNews. MALDIVES. 15 February 2012.

- ↑ AFP (8 February 2012). "Maldives mob smashes Buddhist statues in national museum". Al Arabiya. MALE.

- ↑ "Self-denial of heritage in Maldives sends message to Establishments". TamilNet. 16 February 2012.

- ↑ BAJAJ, VIKAS (13 February 2012). "Vandalism at Maldives Museum Stirs Fears of Extremism". The New York Times. MALE, Maldives.

- ↑ BAJAJ, VIKAS (13 February 2012). "Vandalism at Maldives Museum Stirs Fears of Extremism". The 4 Freedoms Library. MALE, Maldives: The New York Times.

- ↑ Jayasinghe, Amal (12 February 2012). "Trouble in paradise: Maldives and Islamic extremism". Agence France-Presse. MALE.

- ↑ AFP (12 February 2012). "Trouble in paradise: Maldives and Islamic extremism". Al Arabiya. MALE.

- ↑ Editor (23 February 2012). "35 Invaluable Hindu and Buddhist Statues Destroyed in Maldives by Extremist Islamic Group". The Chakra News. Maldives.

- ↑ "Vandalised Maldives museum to seek India`s help". Zee News. Male. 15 February 2012.

- ↑ FRANCIS, KRISHAN (14 February 2012). "Maldives Museum Reopens Minus Smashed Hindu Images". Associated Press. COLOMBO, Sri Lanka.

- ↑ Francis, Krishan (14 February 2012). "Maldives museum reopens minus smashed Hindu images". Associated Press.

- ↑ Francis, Krishan. "Maldives national museum reopens minus valuable smashed pre-Islamic era Hindu images". Associated Press. COLOMBO.

- ↑ "Maldives national museum reopens minus valuable smashed pre-Islamic era Hindu images". AP. COLOMBO, Sri Lanka.

- ↑ "Protection of Antiquities Regulations 21st November, 1932 Government Notice 402 of 1932, as Amended by Government Notices 127 of 1935 and 338 of 1939". Malta Environment and Planning Authority. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ↑ Luke, Harry (1960). Malta: An Account and an Apreciation. Harrap. p. 60.

- ↑ Gauci, Gregory. "The Clock Tower". Birgu Local Council. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014.

- ↑ "Auberge d'Allemagne". Times of Malta. 17 November 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ "Birgu's Auberge d'Italie". Times of Malta. 1 December 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Cilia, Daniel. "Destroyed Megalithic Sites – Kordin I". The Megalithic Temples of Malta. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ↑ Cilia, Daniel. "Destroyed Megalithic Sites – Kordin II". The Megalithic Temples of Malta. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "Fort Manoel restoration works impress". Times of Malta. 15 February 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ "Malta's Cultural Heritage". Superintendence of Cultural Heritage. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Azzopardi, Joe (May 2014). "The Gourgion Tower – Gone but not Forgotten (Part 2)" (PDF). Vigilo. Din l-Art Ħelwa (45): 44–47. ISSN 1026-132X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2015.

- ↑ Baldacchino, Godfrey, ed. (2012). Extreme Heritage Management: The Practices and Policies of Densely Populated Islands. Berghahn Books. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780857452603.

- ↑ "Permit to demolish palazzo façade valid – MEPA". Times of Malta. 23 January 2003. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016.

- ↑ Said, Edward (November 2017). "St Ignatius Villa, Scicluna Street, St Julians – Heritage Assessment" (PDF). Architecture XV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2018.

- ↑ "Workers send Villa St Ignatius structure crashing down". 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018.

- ↑ PHOTO IN THE NEWS: Myanmar's Jeweled Temple Damaged. National Geographic News. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Deepak Nagpal (25 April 2015). "LIVE: Two major quakes rattle Nepal; historic Dharahara Tower collapses, deaths reported in India". Zee News. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Historic Dharahara tower collapses in Kathmandu after earthquake". DNA India. 25 April 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ The Ruins of Harappa. The Daily Times. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Harappan Civilization: Current Perspective and its Contribution – By Dr. Vasant Shinde. AIS. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ↑ Edmund Burke, Ervand Abrahamian, Ira Marvin Lapidus (1988). Islam, Politics, and Social Movements. University of California Press. p. 156. ISBN 9780520068681.

- ↑ "Taliban and traffickers destroying Pakistan's Buddhist heritage". AsiaNews.it. 22 October 2012.

- ↑ "Taliban trying to destroy Buddhist art from the Gandhara period". AsiaNews.it. 27 November 2009.

- ↑ Rizvi, Jaffer (6 July 2012). "Pakistan police foil huge artefact smuggling attempt". BBC News.

- ↑ Malala Yousafzai (8 October 2013). I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban. Little, Brown. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-316-32241-6.

- ↑ Wijewardena, W.A. (17 February 2014). "'I am Malala': But then, we all are Malalas, aren't we?". Daily FT.

- ↑ Wijewardena, W.A (17 February 2014). "'I am Malala': But Then, We All Are Malalas, Aren't We?". Colombo Telegraph.

- ↑ Jeffrey Hays. "EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM".

- ↑ "Another attack on the giant Buddha of Swat". AsiaNews.it. Pakistan. 10 November 2007. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "Buddha attacked by Taliban gets facelift in Pakistan". Dawn. JAHANABAD, Pakistan. Associated Press. 25 June 2012.

- ↑ Khaliq, Fazal (7 November 2016). "Iconic Buddha in Swat valley restored after nine years when Taliban defaced it". DAWN.

- ↑ "Turnul unei biserici vechi de 700 de ani s-a prăbuşit pentru că nu a fost reabilitată". Digi24. 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Andreea Tobias, Mihaela Grădinaru (20 February 2016). "Braşov: Turnul bisericii evanghelice din Rotbav s-a prăbuşit. Nu sunt victime". Mediafax.

- ↑ "Nezakonny remont pamyatnika ... (Незаконный ремонт памятника в Москве привел к его разрушению)" (in Russian). Newmsk. 4 April 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ↑ "Protesters angry over destruction of 'Mephistopheles' in St Petersburg". euronews.

- ↑ "Uproar in St. Petersburg after demon statue destroyed". DW.COM.

- ↑ "Hundreds protest smashing of 'Mephistopheles' in St Petersburg".

- ↑ Movrin, David. 2013. Yugoslavia in 1949 and its gratiae plenum: Greek, Latin, and the Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (Cominform). In György Karsai et al. (eds.), Classics and Communism: Greek and Latin behind the Iron Curtain, pp. 291–329. Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani, p. 319.

- ↑ All RFE/RL sites (2002-06-28). "Reindl, Donald F. 2002. Slovenia's Vanishing Castles. ''RFE/RL Balkan Report'' (June 28)". Rferl.org. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- 1 2 "조선왕조실록 : 요청하신 페이지를 찾을 수 없습니다". sillok.history.go.kr. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ Muller, Charles. Korean Buddhism: A Short Overview.

- 1 2 "Monumentos desaparecidos". Archived from the original on 17 November 2011.

- ↑ (in Spanish) El martirio de los libros: una aproximación a la destrucción bibliográfica durante la Guerra Civil ( Archived 27 September 2011 at WebCite)

- ↑ "Un rayo destruye un emblemático santuario en Muxía". El Mundo. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013.

- ↑ "Palace of King Parakramabahu the Great - AmazingLanka.com". AmazingLanka.com.

- ↑ Fisk, Robert (5 August 2012). "Syria's ancient treasures pulverised". The Independent. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Taştekin, Fehim (12 January 2017). "Return to Aleppo: A squandered legacy". Al-Monitor.

- ↑ "Ancient Syrian temple damaged in Turkish raids against Kurds". timesofisrael. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ "Syrian government says Turkish shelling damaged ancient temple". reuters. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Historic England. "Ruined Cathedral Church of St Michael, Coventry (1076651)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ "Clandon Park House in Surrey hit by major fire". BBC News. 29 April 2015.

- ↑ "Exeter fire: Royal Clarence Hotel collapses in blaze". BBC News. 29 October 2016.

- ↑ "Glasgow School of Art may be beyond repair after second fire". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ↑ The 1973 Fire, National Personnel Records Center

- ↑ Stanglin, Doug (24 April 2014). "Site of rare Indian artifacts paved over in California". USA Today. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ↑ "CREATED THE "EIGHTH WONDER"". Legacy Washington. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ "Robo de la bandera de los "33" originó nuevo debate político". 13 April 2000. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ "Desaparicion de la bandera de los 33 por el OPR-33". www.uruguaymilitaria.com. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ Tearing the Historic Fabric: The Destruction of Yemen’s Cultural Heritage. Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Yemen suffers cultural vandalism during its war. The New Arab. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ↑ Yemen: the Unesco heritage slowly being destroyed. The Telegraph. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ↑ The threat to Yemen’s heritage. Apollo. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

Sources

- Gaya Nuño, Juan Antonio. La arquitectura española en sus monumentos desaparecidos. Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, 1961.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan (1997). Spiritual Genocide: A survey of destroyed, damaged and desecrated churches, monasteries and other church buildings during the war 1991–1995 (1997). Belgrade: Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Further reading

- Bajgora, Sabri (2014). Destruction of Islamic Heritage in the Kosovo War 1998–1999. Pristina: Interfaith Kosovo, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kosovo. ISBN 9789951595025.

- Narain, Harsh (1993). The Ayodhya Temple Mosque Dispute: Focus on Muslim Sources. Delhi: Penman Publishers. ISBN 9788185504162

- Shourie, Arun, S.R. Goel, Harsh Narain, J. Dubashi and Ram Swarup. Hindu Temples - What Happened to Them Vol. I, (A Preliminary Survey) (1990) ISBN 81-85990-49-2

External links

- Targeting History and Memory, SENSE - Transitional Justice Center (dedicated to the study, research, and documentation of the destruction and damage of historic heritage during the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. The website contains judicial documents from the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)).

- http://www.cracked.com/article_20149_6-mind-blowing-archeological-discoveries-destroyed-by-idiocy_p2.html

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_692036.jpg)