Abyla

Ruins of Paleochristian Roman basilica in current Ceuta | |

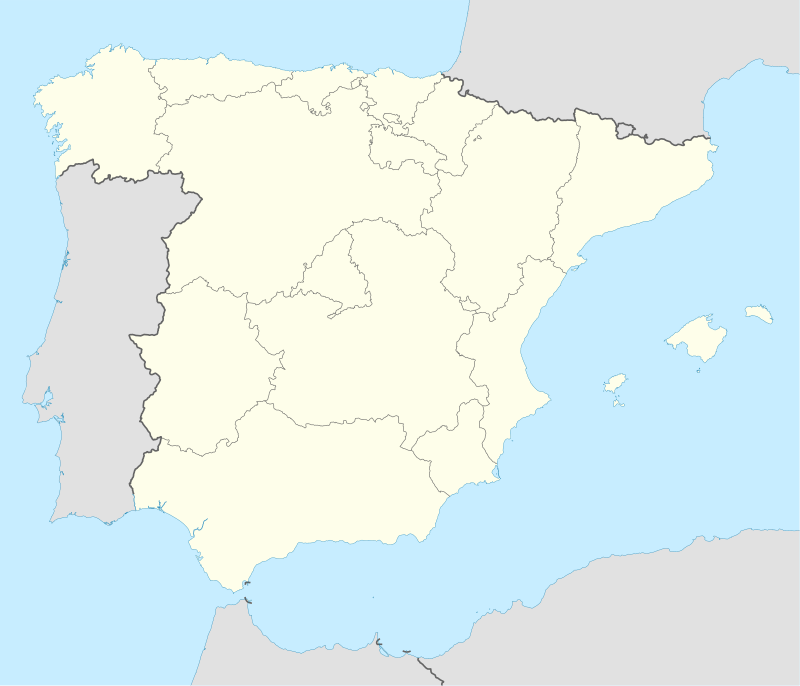

Shown within Spain | |

| Alternative name | Ad Septem Fratres |

|---|---|

| Location | Spain |

| Region | Ceuta |

| Coordinates | 35°53′18″N 5°18′56″W / 35.888333°N 5.315556°WCoordinates: 35°53′18″N 5°18′56″W / 35.888333°N 5.315556°W |

Abyla (called also Ad Septem Fratres or simply "Septem") was a Roman colony in Mauretania Tingitana. It was an ancient city that existed in what is now the downtown of Ceuta.

Characteristics

Septem's location on the southern side of the Gibraltar Strait has made it an important commercial trade and military way-point for many cultures, beginning in the fifth century BC with the Carthaginians (who first called the city by the name "Abyla").

It was known variously in Ancient Greek as: Ἀβύλη, Ἀβύλα, Ἀβλύξ, or Ἀβίλη στήλη – Abyle, Abila, Ablyx or Abile Stele – "Pillar of Abyle")[1] and in the Latin derivation from Greek as Abyla Mons Columna ("Mount Abyla" or "Column of Abyla"). Together with Gibraltar on the European side, it formed one of the famous "Pillars of Hercules".[1][2] Later, it was renamed for a formation of seven surrounding smaller mountains, collectively referred to as Septem Fratres ('[The] Seven Brothers') by Pomponius Mela, which lent their name to a Roman fortification known as Castellum ad Septem Fratres.[1]

It was not until the Romans took control of the region in 42 AD that the port city, then named "Septem Fratres", assumed an almost exclusively military purpose. The city become a Roman colonia with full rights for the citizens under emperor Claudius.

.jpg)

Septem flourished economically in the Roman Empire and developed one of the main production places for fish salting commerce and industry. The city was connected with southern Roman Hispania not only for commerce, but even administratively. Efficient Roman roads connected Septem with Tingis and Volubilis, facilitating trade for military movements of legions.

In the beginning of the first century, under Augustus, the citizens of Septem used mainly the Phoenician language. Soon after that started the process of Romanization of the inhabitants. As a result, most of Septem's inhabitants spoke Latin in the fourth century, but there was also a sizable local community of romanised Berbers, who spoke their Berber dialect mixed with some Phoenician loanwords. When the city fell to the Byzantines in the sixth century, Greek was added to Latin as the official language.

Septem was an important Christian center in Mauretania Tingitana since the fourth century (as recently discovered ruins of a Roman basilica show [3]); it is thus the only place in the current Maghreb where Roman heritage (represented by Christianity) has continued uninterrupted even to the present day.

History

When the Phoenicians arrived in what is now Ceuta, they found a small Berber settlement. Carthage created and used the little port of Abyla, but the Romans made it an important port and city. They named it "Septem Frates" because of the seven little hills (that looked like seven brothers, or 'septem frates' in Latin) of the promontory where the city lies.

From the time of Augustus, the city started to grow with the name of Septem (or even "Septa"). Some Italian colonists moved to Septem and started the use of Latin, but the population -made mostly of Berbers- continued to use the Phoenician language mixed with local berberisms. In the second century, the romanization of Septem was nearly complete, and the use of Phoenician disappeared. Under Septimius Severus, the economy enjoyed a huge development, fueled by the fish conserve & salting industry. Septem had nearly 10,000 inhabitants in the late fourth century, under emperor Theodosius I, and was nearly fully Christian and Latin speaking, according to historian Theodore Mommsen.[4]

Around 140 AD in Septem there was an expansion of its salting industry, with new production centers located near the Forum. Its heyday extends until the second half of the third century. After these years, the production centers were abandoned until the full recovery of the empire (in the 4th and 5th centuries), according even to studies by Enrique Cravioto on monetary use.[5] Salting produce was exported in jars manufactured in places near the city. These exports were directed mainly toward Hispania, with whom Septem had intense business contact.

.png)

Socially, in Claudius' and Nero's reigns, there emerged the presence in Septem of wealthy Roman citizens who enjoyed the "ius romanum" or right to full citizenship, as documented by the funerary inscriptions found around the Septem basilica. In the second century under Trajan, a local Senate was made available for the wealthy Septem members of the "Ordo decurionum" (who in Roman society were the highest nobility).

Septem changed hands again approximately after four centuries of Roman domination, when Vandal tribes ousted the Romans in 426 AD.[6] After being controlled by the Visigoths, it then became an outpost of the Byzantine Empire, called Άβυλα in Ancient Greek.

All the territory west of Caesarea had already been lost by the Vandals to the Berber "Mauri", but a re-established "Dux Mauretaniae" kept a Byzantine military unit at Septem. This was the last Byzantine outpost in Mauretania Tingitana; the rest of what had been the Roman province was united with the Byzantine part of Andalusia, under the name, "Prefecture of Africa". Most of the North African coast was later organised as the civilian Exarchate of Carthage, a special status, in view of the outpost defense needs.

Around 710, as Muslim armies approached the city, its Byzantine governor, Julian (described also as King of the Ghomara Berbers), changed his allegiance, and exhorted the Muslims to invade the Iberian Peninsula. Under the leadership of the Berber general Tariq ibn Ziyad, the Muslims used Ceuta as a staging ground for an assault on the Visigothic Iberian Peninsula. After Julian's death, the Berbers took direct control of the city, which the local Berber tribes resented. They destroyed Ceuta during the Kharijite rebellion led by Maysara al-Matghari in 740 AD.

Septem remained as a small village (populated even by a few Christians), nearly all in ruins, until it was resettled in the ninth century by Mâjakas, chief of the Majkasa Berber tribe, who started the short-lived Banu Isam dynasty.[7]

The episode of the martyrdom of Saint Daniele Fasanella[8] and his Franciscans in 1227 AD, showed that Christians were still present in "Septa" (as it was known in Arabic); this Christian community remained on the outskirts of the city until the arrival of the Portuguese in the 15th century. Since then, the city -renamed Ceuta- has remained in Christian hands (Portuguese and Spanish), and now has a majority of the population speaking Spanish.

The Berber Christians of Mauretania's Septem seem to have adopted Christianity with nearby Spain, and are considered the only survivors of the early Christian faith once native to Roman Africa (using perhaps also the disappeared African Romance language), according to Robin Daniel,.[9]

The Cathedral of St Mary of the Assumption (Spanish: Catedral de Santa María de la Asunción) is the Roman Catholic cathedral of the Spanish city of Ceuta.[10] The Cathedral is a 15th-century structure, built on the site of a sixth-century Christian church of "Septem" and is the center of Catholicism in the city since the Roman Catholic Diocese of Ceuta was "erected" on 4 April 1417.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Philip Smith, BA (1854). "Abyla". In William Smith, LLD. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, illustrated by numerous engravings on wood. London:Upper Gower Street and Ivy Lane, Paternoster Row; Albemarle Street: Walton and Maberly; John Murray. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ↑ Abyla. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ↑ Roman basilica article, with related video

- ↑ Theodore Mommsen. "The Provinces of the Roman Empire". Section: Africa

- ↑ Cravioto, Enrique. "La circulación monetaria alto-imperial en el norte de la Mauretania Tingitana"

- ↑ Septem byzantine

- ↑ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Bernard Lewis; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1994). "The Encyclopaedia of Islam". Brill. p. 690

- ↑ San Daniele Fasanella martyrdom (in Italian)

- ↑ Christianity of Romanized Berbers

- ↑ Hugh Griffin (1 February 2010). Ceuta Mini Guide. Horizon Scientific Press. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-0-9543335-3-9. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

Bibliography

- Conant, Jonathan. Staying Roman : conquest and identity in Africa and the Mediterranean (pp. 439–700). Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521196973. Cambridge, 2012

- Cravioto, Enrique. La circulación monetaria alto-imperial en el norte de la Mauretania Tingitana. Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Cuenca, 2007

- Mommsen, Theodore. The Provinces of the Roman Empire, Section Africa. Ed Barnes & Noble. New York, 2005

- Noé Villaverde, Vega. Tingitana en la antigüedad tardía, siglos III-VII: autoctonía y romanidad en el extremo occidente mediterráneo. Ed. Real Academia de la Historia. Madrid, 2001 ISBN 8489512949

- Robin, Daniel. Faith, Hope and love in the early churches of North Africa (This Holy Seed). Tamarisk Publications, Chester, United Kingdom ISBN 978 0 9538565 3 4

- Talbi, Mohammed. Le Christianisme maghrébinin "Indigenous Christian Communities in Islamic Lands". M. Gervers and R. Bikhazi. Toronto, 1990.

%2C_Algeria_04966r.jpg)