Jordanian Arabic

| Jordanian Arabic | |

|---|---|

| اللهجة الاردني | |

| Native to | Jordan |

Native speakers | 6.24 million (2016)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Arabic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

Either:avl – Levantine Bedawiajp – South Levantine |

| Glottolog |

sout3123[2]east2690[3] |

| |

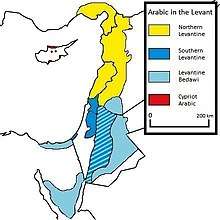

Jordanian Arabic is a continuum of mutually intelligible varieties of Levantine Arabic spoken by the population of the Kingdom of Jordan. Jordanian Arabic varieties are Semitic, with lexical influences from English, Turkish and French. They are spoken by more than 6 million people, and understood throughout the Levant and, to various extents, in other Arabic-speaking regions. As in all Arab countries, language use in Jordan is characterized by diglossia; Modern Standard Arabic is the official language used in most written documents and the media, while daily conversation is conducted in the local colloquial varieties.

Aside from the various dialects, one must also deal with the differences in addressing males, females, and groups; plurals and verb conjugations are highly irregular and difficult to determine from their root letters; and there are several letters in the Arab alphabet that are difficult for an English speaker to pronounce.

Regional Jordanian Arabic varieties

Although there is a common Jordanian dialect mutually understood by most Jordanians, the daily language spoken throughout the country varies significantly through regions. These variants impact altogether pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary.

The Jordanian Arabic comprises five varieties:

- Hybrid variety (Modern Jordanian): It is the most current spoken language among Jordanians. This variety was born after the designation of Amman as capital of the Jordanian kingdom early in the 20th century. It is the result of the merger of the language of populations who moved from northern Jordan, southern Jordan and later from Palestine. For this reason, it mixes features of the Arabic varieties spoken by these populations. The emergence of the language occurred under the strong influence of the northern Jordanian dialect. As in many countries English is used to substitute many technical words, even though these words have Arabic counterparts in modern standard Arabic.

- Northern varieties: Mostly spoken in the area from Amman to Irbid in the far north. As in all sedentary areas, local variations are many. The pronunciation has /q/ pronounced [g] and /k/ mostly ([tʃ]). This dialect is part of the southern dialect of the Levantine Arabic language.

- Southern/Moab: Spoken in the area south of Amman, in cities such as Karak, Tafilah, Ma'an, Shoubak and their countrysides, it is replete with city-to-city and village-to-village differences. In this dialect, the pronunciation of the final vowel (æ~a~ə) commonly written with tāʾ marbūtah (ة) is raised to [e]. For example, Maktaba (Fuṣḥa) becomes Maktabe (Moab), Maktabeh (North) and Mektaba (Bedawi). Named after the ancient Moab kingdom that was located in southern Jordan, this dialect belongs to the outer southern dialect of the Levantine Arabic language.

- Bedouin: Is spoken by Bedouins mostly in the desert east of the Jordanian mountains and high plateau, and belongs to the Bedawi Arabic. This dialect is not widely used in other regions. It is often considered as truer to the Arabic language, but this is a subjective view that shows no linguistic evidence. Note that non-Bedouin is also spoken in some of the towns and villages in the Badia region east of Jordan's mountain heights plateau, such as Al-Azraq oasis.

- Aqaba variety

Pronunciation

General remarks

The following sections focus on modern Jordanian.

There is no standard way to write Jordanian Arabic. The sections below use the alphabet used in standard Arabic dialect studies, and the mapping to IPA is given.

Stress

One syllable of every Jordanian word has more stress than the other syllables of that word. Some meaning is communicated in Jordanian by the location of the stress or the tone of the vowel. This is much truer than in other Western languages in the sense that changing the stress position changes the meaning (e.g. ['katabu] means they wrote while [katabu'] means they wrote it). This means one has to listen and pronounce the stress carefully.

Consonants

There are some phonemes of the Jordanian language that are easily pronounced by English speakers; others are completely foreign to English, making these letters difficult to pronounce.

| Phoneme | IPA | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| /b/ | [b] | As English b. |

| /t/ | [t] | As French or Spanish t (without the English aspiration). |

| /ṯ/ | [θ] | As English thief. It is rare, mostly in words borrowed from MSA. |

| /j/ | [dʒ] | Either hard [dʒ] as in English jam or soft [ʒ] as in English vision (depending on accent and individual speaker's preference). |

| /ḥ/ | [ħ] | This h is pronounced deep in the throat, deeper than English h. Imagine you want to blow fog on your sunglasses. |

| /ẖ/ | [x] | As German ch in ach! or as Spanish jota. |

| /d/ | [d] | As English d |

| /ḏ/ | [ð] | As English this. It is rare, mostly in words borrowed from MSA. |

| /r/ | [ɾˤ] | Simultaneous pronunciation of r and a weak ayn below. |

| /ṛ/ | [ɾ] | As is Scottish, Italian or Spanish. |

| /z/ | [z] | As English z. |

| /s/ | [s] | As English s. |

| /š/ | [ʃ] | As English sh. |

| /ṣ/ | [sˤ] | Simultaneous pronunciation of s and a weak ayn below. |

| /ḍ/ | [dˤ] | Simultaneous pronunciation of d and a weak ayn below. |

| /ṭ/ | [tˤ] | Simultaneous pronunciation of d and a weak ayn below. |

| /ẓ/ | [zˤ] | Simultaneous pronunciation of z and a weak ayn below. |

| /ʿ/ | [ʕ] | This is the ayn. It is pronounced as /ḥ/ but with vibrating larynx. It is a voiced pharyngeal fricative sound produced as deep as possible in the throat. |

| /ġ/ | [ɣ] | As Spanish pagar, or Greek gato; similar also to r in Parisian French or German. |

| /f/ | [f] | As English. |

| /q/ | [q] | It is a voiceless occlusive as [k], but pronounced further back in the mouth, at the uvula. It is rare, mostly in words borrowed from MSA apart from the dialect of Ma'daba or that of the Hauran Druzes. |

| /k/ | [k] | As French or Spanish [k] in ca,co,cu (without the English aspiration). |

| /l/ | [l] | As English list (never a dark l as in call). |

| /m/ | [m] | As English. |

| /n/ | [n] | As English. |

| /h/ | [h] | As English. |

| /w/ | [w] | As English. |

| /y/ | [j] | As English in yet, yellow etc. |

Vowels

Contrasting with the rich consonant inventory, Jordanian Arabic has much fewer vowels than English. Yet, as in English, vowel duration is relevant (compare /i/ in bin and bean).

| Phoneme | IPA | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| /a/ | [a] or [ɑ] | As English hut or hot (the latter linked to the presence of ṣ, ḍ, ṭ, ẓ, ẖ, ʿ, ḥ or ṛ). |

| /ā/ | [a:] or [ɑ:] | The previous one but longer (you hear [ɑ:] in father). Amman is [ʕɑm'ma:n]. |

| /i/ | [ı] | As in English hit. |

| /ī/ | [i:] | As in English heat. |

| /u/ | [u] | As in English put. |

| /ū/ | [u:] | As in English fool. |

| /e/ | [e] | French été. |

| /ē/ | [e:] | As in English pear, or slightly more closed. |

| /o/ | [o] | As in French côté. |

| /ō/ | [o:] | As French (faune) or German (Sohn). |

Note : It is tempting to consider /e/ and /i/ as variants of the same phoneme /i/, as well as /o/ and /u/. For the case of e/i, one can oppose 'ente' (you, masculine singular) to 'enti' (you, feminine singular), which makes the difference relevant at least at the end of words.

Grammar

The grammar in Jordanian is quite the mixture. Much like Hebrew and Arabic, Jordanian is a Semitic language at heart, altered by the many influences that developed over the years.

Article definitions

- el/il-

- This is used in most words that don't start with a vowel in the beginning of a sentence. It is affixed onto the following word.

Il-bāb or el-port meaning the door.

- e()-

- A modified "el" used in words that start with a consonant produced by the blade of the tongue (t, ṭ, d, ḍ, r, z, ẓ, ž, s, ṣ, š, n. Sometimes [l] and [j] as well depending on the dialect). This causes a doubling of the consonant.

This e is pronounced as in a rounded short backward vowel or as in an e followed by the first letter of the word that follows the article. For example: ed-desk meaning the desk, ej-jakét meaning the jacket, es-seks meaning the sex or hāda' et-téléfón meaning that is the telephone.

- l'

- This is elided into l' when the following word starts with a vowel. For example: l'yüniversiti meaning the University, l'üniform meaning the uniform or l'ēyen meaning the eye.

'l

- Because of Arabic phonology, the definite article can be also elided onto the preceding word on the condition that it ends with a vowel and the word following the article starts with a constant that doesn't require an e()-, it is elided into an 'l and affixed to the end of the word. For example: Lámma'l kompyütar bıştağel means when the computer works.

Pronouns

- ana

- I (singular)(male)(female) (Modern Dialect)

- enta

- You (singular)(male) (Modern Dialect)

- enti

- You (singular)(female) (Modern Dialect)

- entu

- You (plural)(male) (Modern Dialect)

- enten

- You (plural)(female) (Hardly used any more)

- huwwe

- He (Standard Dialect)

- hiyye

- She (Modern Dialect)

- hiyya

- She (Eastern and Southern Dialect)

- humme

- They (plural)(male) (Modern Dialect)

- henne

- They (plural)(female) (Hardly used any more)

- ıħna

- We (Modern Dialect)

Note: The Modern dialect is understood by almost everyone in the country and the entire region.

Possessiveness

Similar to ancient and modern semitic languages, Jordanian adds a suffix to a word to indicate possession.

- ktāb

- book

- ktāb-i

- my book

- ktāb-ak

- your book (singular, male)

- ktāb-ek

- your book (singular, female)

- ktāb-kom

- your book (plural, male)

- ktāb-ken

- your book (plural, female, bedouin)

- ktāb-o

- his book

- ktāb-ha

- her book

- ktāb-hom

- their book (plural, male)

- ktāb-hen

- their book (plural, female bedouin)

- ktāb-na

- our book

General sentence structure

In a sentence, the pronouns change into prefixes to adjust to the verb, its time and its actor. In present perfect and participle with a verb that starts with a consonant Ana becomes ba, Inta becomes 'Bt', Inti becomes Bıt and so-on.

For example: The verb hıb means to love, Bahıb means I love, Bthıb means you love, Bahıbo means I love him, Bıthıbha means she loves her, Bahıbhom means I love them, Bahıbhālí means I love myself.

Qdar is the infinitive form of the verb can. Baqdar means I can, I can't is Baqdareş, adding an eş or and ış to the end of a verb makes it negative; if the word ends in a vowel then a ş should be enough.

An in-depth example of the negation: Baqdarelhomm figuratively means I can handle them, Baqdarelhommeş means I cannot handle them, the same statement meaning can be achieved by Baqdareş l'ıl homm

Legal status and writing systems

The Jordanian Levantine is not regarded as the official language even though has diverged significantly from Classic Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), or even the colloquial MSA.[4][5][6] A large number of Jordanians, however, will call their language "Arabic" while they will refer to the original Arabic language as Fusħa. This is common in many countries that speak languages or dialects derived from Arabic and can prove to be quite confusing. The writing system varies; whenever a book is published, it is usually published in English, French, or in MSA and not in Levantine.[4][5][6] There are many ways of representing Levantine Arabic in writing. The most common is the scholastic Jordanian Latin alphabet system which uses many accents to distinguish between the letters (this system is used within this article). Other Levantine countries, however, use their own alphabets and transliterations, making cross-border communication inconvenient.[7]

External Influences

British English has a great influence on Jordanian Levantine,[8] depending on the region. English is widely understood in many regions, especially in the western part of the country. English vocabulary has been adopted replacing native Arabic vocabulary in many cases. Literary Arabic is spoken in formal TV programs, and in Modern Standard Arabic classes, it is used to quote poetry and historical phrases. It is also the language used to write and read in formal situations if English is not being used. However, formal Arabic is never spoken during regular conversations, and can prove to be difficult because it removes loan words from English or French origins and replaces them with proper Standard Arabic-derived nouns and verbs. Modern Standard Arabic is taught in most schools and a large number of Jordanian citizens are proficient in reading and writing formal Arabic. However, foreigners residing in Jordan who learn the Levantine language generally find it difficult to comprehend formal MSA, particularly if they did not attend a school that teaches it.

Other influences include French, Turkish and Persian. Many loan words from these languages can be found in the Jordanian dialects, though not so much as English. However, students also have the option of learning French in schools. Currently, there is a small society of French speakers called Francophone and it is quite notable in the country. The language is also spoken by people who are interested in the cultural and commercial features of France.

References

- ↑ "Jordan". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Jordanian Arabic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Jordanian Arabic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 Jordanian Arabic phrasebook – iGuide Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. Iguide.travel. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- 1 2 Ethnologue report for language code: ajp. Ethnologue.com. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- 1 2 iTunes – Podcasts – Jordanian Arabic Language Lessons by Peace Corps Archived 21 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. Itunes.apple.com (16 February 2007). Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ↑ Syria – Diana Darke – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 19 October 2011.

- ↑ (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20111008153258/http://www.lit.az/ijar/pdf/jes/2/JES2010%282-5%29.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

See also

External links