Kunta Kinte

| Kunta Kinte | |

|---|---|

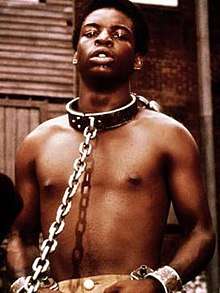

LeVar Burton as Kunta Kinte in the TV miniseries Roots | |

| Born |

c. 1750 Juffure, The Gambia |

| Died |

c. 1822 (aged c.71–77) Spotsylvania County, Virginia |

| Family |

Omoro (father) Binta (mother) Belle (wife) Kizzy (daughter) George (grandson) Tom (great-grandson) Alex Haley (descendant) |

Kunta Kinte (c. 1750 – c. 1822; /ˈkuːntɑː

Kunta Kinte's life story also figured in two US-made television series based on the book: the original 1977 TV miniseries Roots,[2] and a 2016 remake of the same name. In the original miniseries, the character was portrayed as a teenager by LeVar Burton and as an adult by John Amos. In the 2016 miniseries, he is portrayed by Malachi Kirby.[3] Additionally, Burton reprised his role as Kunta in the TV movie Roots: The Gift, a fictional tale originally broadcast during the 1988 Christmas season.

Life as told in Roots

According to Roots, Kunta Kinte was born circa 1750 in the Mandinka village of Juffure, in the Gambia. He was raised in a Muslim family.[4][5] One day in 1767, while Kunta was searching for wood to make a drum for his younger brother, four men chased him, surrounded him, and took him captive. Kunta awoke to find himself blindfolded, gagged, bound, and a prisoner. He and others were put on the slave ship the Lord Ligonier for a four-month Middle Passage voyage to North America.

Kunta survived the trip to Maryland and was sold to a Virginia plantation owner in Spotsylvania County, Master Waller, whose wife, Elizabeth, renamed him Toby. He rejected the name imposed upon him by his owners and refused to speak to others. After being recaptured during the last of his four escape attempts, the slave catchers gave him a choice: he would be castrated or have his right foot cut off. He chose to have his foot cut off, and the men cut off the front half of his right foot. As the years passed, Kunta resigned himself to his fate and became more open and sociable with his fellow slaves, while never forgetting who he was or where he came from.

Kunta married an enslaved woman named Bell Waller and they had a daughter whom they named Kizzy (Keisa, in Mandinka), which in Kunta's native language means "to stay put" (he gave her this name in order to protect her from being sold away). When Kizzy was in her late teens, she was sold away to North Carolina when her master discovered that she had written a fake traveling pass for an enslaved young man with whom she was in love (she had been taught to read and write secretly by Missy Anne, the niece of the plantation owner). Her new owner, Thomas Moore, immediately raped her and fathered her only child whom he named George Moore, after his own father. George II spent his life with the tag "Chicken George", because of his assigned duties of tending to his master's cockfighting birds.

In the novel, Kizzy never learns her parents' fate. She spends the remainder of her life as a field hand on the Moore plantation in North Carolina. According to the 1977 miniseries, Kizzy is taken back to visit the Reynolds plantation later in life. She discovers that her mother was sold off to another plantation and that her father died of a broken heart two years later, in 1822. She finds his grave, where she crosses out his slave name Toby from the tombstone and writes his original name Kunta Kinte instead. Kizzy is Haley's only ancestor in the genealogy link to Kunta Kinte whose entire lifetime was spent in slavery.

The latter part of the book tells of the generations between Kizzy and Alex Haley, describing their suffering, losses and eventual triumphs in America. Alex Haley claimed to be a seventh-generation descendant of Kunta Kinte.[6]

Historical accuracy

Haley claimed that his sources for the origins of Kinte were oral family tradition and a man he found in the Gambia named Kebba Kanga Fofana, who claimed to be a griot with knowledge about the Kinte clan. He described them as a family in which the men were blacksmiths, descended from a marabout named Kairaba Kunta Kinte, originally from Mauritania. Haley quoted Fofana as telling him: "About the time the king's soldiers came, the eldest of these four sons, Kunta, went away from this village to chop wood and was never seen again."[7]

However, journalists and historians later discovered that Fofana was not a griot. In retelling the Kinte story, Fofana changed crucial details, including his father's name, his brothers' names, his age, and even omitted the year when he went missing. At one point, he even placed Kunta Kinte in a generation that was alive in the twentieth century. It was also discovered that elders and griots could not give reliable genealogical lineages before the mid-19th century, with the single apparent exception of Kunta Kinte. It appears that Haley had told so many people about Kunta Kinte that he had created a case of circular reporting. Instead of independent confirmation of the Kunta Kinte story, he was actually hearing his own words repeated back to him.[8][9]

After Haley's book became nationally famous, American author Harold Courlander noted that the section describing Kinte's life was apparently taken from Courlander's own novel The African. Haley at first dismissed the charge, but later issued a public statement affirming that Courlander's book had been the source, and Haley attributed the error to a mistake of one of his assistant researchers. Courlander sued Haley for copyright infringement, which Haley settled out of court.

Influence

There is an annual Kunta Kinte Heritage Festival held in Maryland.[10] Kunta Kinte inspired a reggae riddim of the same name, performed by artists including The Revolutionaries,[11] and Mad Professor, and an album, Kunta Kinte Roots by Ranking Dread.[12]

In The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Will Smith's character says, in regard to being punished, "Why don't you just do me like Kunta Kinte and chop off my foot?"[13]

Rapper and songwriter Kendrick Lamar references Kunta Kinte in his 2015 single release, "King Kunta".[14]

Rappers Kanye West and Jay-Z, with spoken word artist J.ivy, reference "the heart of Kunta Kinte" on West's song "Never Let Me Down" from his 2004 album The College Dropout.[15]

Kunta is also mentioned in Busta Rhymes's song "Rhymes Galore" from the 1997 album When Disaster Strikes. [16]

Kunta is mentioned in Bloodhound Gang's song "A Lapdance Is So Much Better When the Stripper Is Crying" from the 2000 album Hooray for Boobies.[17]

Kunta is mentioned in the Ludacris song "Coming 2 America" from his 2001 album Word Of Mouf.[18]

Ice Cube mentions Kunta Kinte, as well as Kunta's slave name, Toby, in his controversial track "No Vaseline".[19]

Kunta is briefly referenced in Missy Elliott's hit "Work It."[20]

In the barbershop scene of Coming To America, the Jewish man calls Akeem "Kunta Kinte."[21]

Season 3, episode 3 of the PBS television show Finding Your Roots With Henry Louis Gates Jr. shared the family trees of actor Maya Rudolph, television writer and producer Shonda Rhimes, and comedian Keenan Ivory Wayans. Keenan references Kunta Kinte in his segment.

See also

- Kunta Kinteh Island in the Gambia

- List of slaves

References

- ↑ "The Roots of Alex Haley". BBC Television Documentary. 1997".

- ↑ Bird, J.B. "ROOTS". Museum.tv. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ↑ Campbell, Sabrina. "Malachi Kirby is Kunta Kinte in 'Roots' Remake". NBC News. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- ↑ Thomas, Griselda (2014). "The Influence of Malcolm X and Islam on Black Identity". Muslims and American Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9780313379635.

- ↑ Hasan, Asma Gull (2002). "Islam and Slavery in Early American History: The Roots Story". American Muslims: The New Generation Second Edition. A&C Black. p. 14. ISBN 9780826414168.

- ↑ "The Kunta Kinte – Alex Haley Foundation". Kintehaley.org. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ↑ Alex Haley, "Black history, oral history, and genealogy", pp. 9–19, at p. 18.

- ↑ Ottaway, Mark (April 10, 1977). "Tangled Roots". The Sunday Times. pp. 17, 21.

- ↑ Wright, Donald R. (1981). "Uprooting Kunta Kinte: On the Perils of Relying on Encyclopedic Informants". History in Africa. 8: 205–217. JSTOR 3171516.

- ↑ "Kunta Kinte Heritage Festival". Kuntakinte.org. Kunta Kinte Celebrations, Inc. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Revolutionaries – Kunta Kinte". Pressure Sounds. Archived from the original on 2007-12-22. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ↑ "Kunta Kinte Roots". Roots Archives. Archived from the original on 2007-10-27. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ↑ "Will Gets a Job". Fresh Prince of Bel Air. Season 2. September 23, 1991. NBC.

- ↑ "Kendrick Lamar – King Kunta". Genius. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- ↑ "10 references to Kunta Kinte in popular culture to get you ready for the Roots remake". Guide. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

- ↑ "Busta Rhymes - Rhymes Galore". Genius. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- ↑ "Bloodhound Gang - A Lap Dance Is So Much Better When The Stripper Is Crying". Genius. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ↑ "Work that track, whip 'em like Kunta". Genius. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- ↑ "Ice Cube – No Vaseline". Genius. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- ↑ "Missy Elliott – Work It". Genius. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- ↑ "10 Royal Facts About Coming to America". 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2017-11-03.