Biafra

| Republic of Biafra | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967–1970 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

|

Motto: "Peace, Unity, and Freedom." | |||||||||

|

Anthem: "Land of the Rising Sun" | |||||||||

Green: Republic of Biafra | |||||||||

Republic of Biafra in May 1967 | |||||||||

| Status | Secessionist state | ||||||||

| Capital | Enugu | ||||||||

| Common languages |

English and Igbo (predominant) French · Efik · Ekoi · Ibibio · Ijaw | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

• Established | 30 May 1967 | ||||||||

• Rejoins Federal Nigeria | 15 January 1970 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1967 | 77,306 km2 (29,848 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1967 | 13,500,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Biafran pound | ||||||||

| |||||||||

|

Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 762. ISBN 0-313-32384-4.

| |||||||||

Biafra, officially the Republic of Biafra, was a secessionist state in West Africa which existed from 30 May 1967 to January 1970; it was made up of the states in the Eastern Region of Nigeria.

Biafra's attempt to leave Nigeria resulted in the Nigerian Civil War. The state was formally recognised by Gabon, Haiti, Ivory Coast, Tanzania and Zambia.[1] Other nations, which did not give official recognition but provided support and assistance to Biafra, included Israel, France, Spain, Portugal, Norway, Rhodesia, South Africa and the Vatican City.[2][3] Biafra also received aid from non-state actors, including Joint Church Aid, Holy Ghost Fathers of Ireland,[4] and under their direction Caritas International,[5] MarkPress and U.S. Catholic Relief Services.[3]

Its inhabitants were mostly Igbo, who led the secession due to economic, ethnic, cultural and religious tensions among the various peoples of Nigeria. Other ethnic groups that were present were the Efik, Ibibio, Annang, Ejagham, Eket, Ibeno and the Ijaw among others.

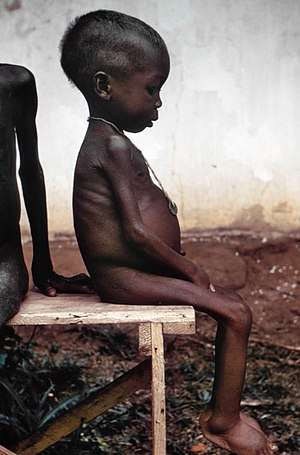

After two-and-a-half years of war, during which almost two million Biafran civilians died from starvation caused by the total blockade of the region by the Nigerian government and the migration of Biafra's Igbo people into increasingly shrinking territory, Biafran forces under the motto of "No-victor, No-vanquished" surrendered to the Nigerian Federal Military Government (FMG), and Biafra was reintegrated into Nigeria. The surrender was facilitated by the Biafran Vice President and Chief of General Staff, Major General Philip Effiong who assumed leadership of the defunct Republic after the original President, Col. Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu fled to Ivory Coast.[6]

Etymology

Little is known about the literal meaning of the word Biafra. The word Biafra most likely derives from the subgroup Biafar or Biafada[7] of the Tenda ethnic group who reside primarily in Guinea-Bissau.[8] Manuel Álvares (1526–1583), a Portuguese Jesuit educator, in his work Ethiopia Minor and a geographical account of the Province of Sierra Leone,[9] writes about the "Biafar heathen" in chapter 13 of the same book.[10] The word Biafar thus appears to have been a common word in the Portuguese language back in the 16th century.

Secession

In 1960, Nigeria became independent of the United Kingdom. As with many other new African states, the borders of the country did not reflect earlier ethnic, cultural or religious boundaries. Thus, the northern region of the country has a Muslim majority, while the southern population is predominantly Christian. Following independence, Nigeria was divided primarily along ethnic lines with a Hausa and Fulani majority in the north, and Yoruba and Igbo majorities in the south-west and south-east respectively.[11]

In January 1966, a military coup occurred during which a group of predominantly Igbo junior army officers assassinated 30 political leaders including Nigeria's Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, and the Northern premier, Sir Ahmadu Bello. The four most senior officers of Northern origin were also killed. Nnamdi Azikiwe, the President, of Igbo extraction, and the premier of the southeastern part of the country were not killed and the commander of the army, General Aguiyi Ironsi seized power to maintain order.[12][13][14]

In July 1966 northern officers and army units staged a counter-coup. Muslim officers named a General from a small ethnic group (the Angas) in central Nigeria, General Yakubu "Jack" Gowon, as the head of the Federal Military Government (FMG). The two coups deepened Nigeria's ethnic tensions. In September 1966, approximately 30,000 Igbo were killed in the north, and some Northerners were killed in backlashes in eastern cities.[15]

Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu proposed a confederated Nigeria. In January 1967, the military leaders and senior police officials of each region met in Aburi, Ghana and agreed on a loose confederation of regions. The Northerners were at odds with the Aburi Accord; Obafemi Awolowo, the leader of the Western Region warned that if the Eastern Region seceded, the Western Region would also, which persuaded the northerners.[15]

After the federal and eastern governments failed to reconcile, on 26 May the Eastern region voted to secede from Nigeria. On 30 May, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, the South Eastern Region's military governor, announced the Republic of Biafra, citing the Easterners killed in the post-coup violence.[11][15][17] The large amount of oil in the region created conflict, as oil was already becoming a major component of the Nigerian economy.[18] The Eastern region was very ill-equipped for war, out-manned and out-gunned by the military of the remainder of Nigeria. Their advantages included fighting in their homeland and support of most South Easterners.[19]

The Nigerian Civil War

The FMG launched "police measures" to annex the Eastern Region on 6 July 1967. The FMG's initial efforts were unsuccessful; the Biafrans successfully launched their own offensive, occupying areas in the mid-Western Region in August 1967. By October 1967, the FMG had regained the land after intense fighting.[15][20] In September 1968, the federal army planned what Gowon described as the "final offensive". Initially the final offensive was neutralised by Biafran troops. In the latter stages, a Southern FMG offensive managed to break through the fierce resistance.[15]

It is believed that one of the major factors that sparked the war was the unilateral declaration of independence for Biafra made by Col. Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu in 1967. He eventually died 41 years after the end of the civil war on 26th November 2011 (aged 78) after a brief illness, many years after the internal conflict, secession and war.[21][22]

Geography

The former Republic of Biafra comprised over 29,848 square miles (77,310 km2) of land,[23] with terrestrial borders shared with Nigeria to the north and west, and with Cameroon to the east. Its coast was on the Gulf of Guinea of the South Atlantic Ocean in the south.

The former country's northeast bordered the Benue Hills and mountains that lead to Cameroon. Three major rivers flow from Biafra into the Gulf of Guinea: the Imo River, the Cross River and the Niger River.[24]

The territory of the former Republic of Biafra is covered nowadays by the reorganized Nigerian states of Cross River, Ebonyi, Enugu, Anambra, Imo, Bayelsa, Rivers, Abia, and Akwa Ibom. While the Igbo people of the current Nigerian state of Delta were not included in Biafra as per Ojukwu's decree founding Biafra, some Delta Igbo did fight on the Biafran secessionist side.

Language

Whilst it existed, the predominant language of Biafra was Igbo.[25] Along with Igbo, there were a variety of other languages, including Efik, Ogoni, Ijaw, Annang and Ibibio. However, English was used as the official language.

Economy

An early institution created by the Biafran government was the Bank of Biafra, accomplished under "Decree No. 3 of 1967".[26] The bank carried out all central banking functions including the administration of foreign exchange and the management of the public debt of the Republic.[26] The bank was administered by a governor and four directors; the first governor, who signed on bank notes, was Sylvester Ugoh.[27] A second decree, "Decree No. 4 of 1967", modified the Banking Act of the Federal Republic of Nigeria for the Republic of Biafra.[26]

The bank was first located in Enugu, but due to the ongoing war, it was relocated several times.[26] Biafra attempted to finance the war through foreign exchange. After Nigeria announced their currency would no longer be legal tender (to make way for a new currency), this effort increased. After the announcement, tons of Nigerian bank notes were transported in an effort to acquire foreign exchange. The currency of Biafra had been the Nigerian pound, until the Bank of Biafra started printing out its own notes, the Biafran pound.[26] The new currency went public on 28 January 1968, and the Nigerian pound was not accepted as an exchange unit.[26] The first issue of the bank notes included only 5 shillings notes and 1 pound notes. The Bank of Nigeria exchanged only 30 pounds for an individual and 300 pounds for enterprises in the second half of 1968.[26]

In 1969 new notes were introduced: £10, £5, £1, 10/- and 5/-.[26]

It is estimated that a total of £115–140 million Biafran pounds were in circulation by the end of the conflict, with a population of about 14 million, approximately £10 per person.[26] In uncirculated condition these are very inexpensive and readily available for collectors.

Military

At the beginning of the war Biafra had 3,000 soldiers, but at the end of the war the soldiers totalled 30,000.[28] There was no official support for the Biafran Army by any other nation throughout the war, although arms were clandestinely acquired. Because of the lack of official support, the Biafrans manufactured many of their weapons locally. Europeans served in the Biafran cause; German born Rolf Steiner was a lieutenant colonel assigned to the 4th Commando Brigade and Welshman Taffy Williams served as a Major until the very end of the conflict.[29] A special guerrilla unit, the Biafran Organization of Freedom Fighters, was established, designed to emulate the insurrectionist guerilla forces of the Viet Cong in the American - Vietnamese War, targeting Nigerian Federal Army supply lines and forcing them to shift forces to internal security efforts.[30]

The Biafrans managed to set up a small yet effective air force. The BAF commander was Jan Zumbach, Early inventory included four World War II American bombers: two B-25 Mitchells, two B-26 Invaders (Douglas A-26), (one piloted by Polish World War II ace Jan Zumbach, known also as John Brown) who bought and flew this plane from Europe to Biafra (officially plane was bought for the Gabon Air Force), a converted Douglas DC-3 and one British De Havilland Dove. In 1968 the Swedish pilot Carl Gustaf von Rosen suggested the MiniCOIN project to General Ojukwu. By early 1969, Biafra had assembled five MFI-9Bs in neighboring Gabon, calling them "Biafra Babies". They were coloured green, were able to carry six 68 mm anti-armour rockets under each wing and had simple sights. The six airplanes were flown by three Swedish pilots and three Biafran pilots. In September 1969, Biafra acquired four ex-Armee de l'Air North American of North American T-6 Texans (T-6G)s, which were flown to Biafra the following month, with another aircraft lost on the ferry flight. These aircraft flew missions until January 1970 and were flown by Portuguese ex-military pilots.[31]

Biafra also had a small improvised navy, but it never gained the success that their air force did. It was headquartered in Kidney Island, Port Harcourt, and commanded by Winifred Anuku. The Biafran Navy was made up of captured craft, converted tugs, and armor-reinforced civilian vessels armed with machine guns or captured 6-pounder guns. It mainly operated in the Niger River delta and along the Niger River.[30]

Legacy

The international humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières originated in response to the suffering in Biafra.[32] During the crisis, French medical volunteers, in addition to Biafran health workers and hospitals, were subjected to attacks by the Nigerian army and witnessed civilians being murdered and starved by the blockading forces. French doctor Bernard Kouchner also witnessed these events, particularly the huge number of starving children, and, when he returned to France, he publicly criticised the Nigerian government and the Red Cross for their seemingly complicit behaviour. With the help of other French doctors, Kouchner put Biafra in the media spotlight and called for an international response to the situation. These doctors, led by Kouchner, concluded that a new aid organisation was needed that would ignore political/religious boundaries and prioritise the welfare of victims.[33]

In their study, Smallpox and its Eradication, Fenner and colleagues describe how vaccine supply shortages during the Biafra smallpox campaign led to the development of the focal vaccination technique, later adopted worldwide by the World Health Organization of the United Nations, which led to the early and cost-effective interruption of smallpox transmission in West Africa and elsewhere.[34]

On 29 May 2000, the Lagos Guardian newspaper reported that the now ex-president Olusegun Obasanjo commuted to retirement of the dismissal of all military persons, soldiers and officers, who fought for the breakaway Republic of Biafra during Nigeria's 1967–1970 civil war. In a national broadcast, he said the decision was based on the belief that "justice must at all times be tempered with mercy".[35]

In July 2006 the Center for World Indigenous Studies reported that government sanctioned killings were taking place in the southeastern city of Onitsha, because of a shoot-to-kill policy directed toward Biafran loyalists, particularly members of the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB).[36][37]

In 2010, researchers from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and University of Nigeria at Nsukka, showed that Igbos born in Biafra during the years of the famine were of higher risk of suffering from obesity, hypertension and impaired glucose metabolism compared to controls born a short period after the famine had ended in the early 1970s. The findings are in line with the developmental origin of health and disease hypothesis suggesting that malnutrition in early life is a predisposing factor for cardiovascular diseases and diabetes later in life.[38][39]

A 2017 paper found that Biafran "women exposed to the war in their growing years exhibit reduced adult stature, increased likelihood of being overweight, earlier age at first birth, and lower educational attainment. Exposure to a primary education program mitigates impacts of war exposure on education. War-exposed men marry later and have fewer children. War exposure of mothers (but not fathers) has adverse impacts on child growth, survival, and education. Impacts vary with age of exposure. For mother and child health, the largest impacts stem from adolescent exposure."[40]

Nationalist Movement

There is no central authority coordinating the Biafran re-secession campaign after the death of Ex-Biafra government leader Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu who worked closely with MASSOB during his lifetime. Historically, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) is the first nonviolent Biafra group that emerged on the present day of the late former Biafra president Gen. Ojukwu in 1999 when MASSOB openly re-hoisted the Biafra flag in Abia State and declared 25 strategies to actualize their peaceful goal. After the death of Gen. Ojukwu in 2011, numerous groups have emerged advocating for a separate country for the people of south-eastern Nigeria. Biafra groups continue to surface after the death of Ojukwu. To advance Biafra restoration, MASSOB leader Chief Ralph Uwazuruike established Radio Biafra in the United Kingdom (Great Britain) in 2009, with Mr. Nnamdi Kanu as his radio director; later Kanu was said to have been dismissed from MASSOB because of accusations of supporting violence that is against MASSOB philosophy.[41] .[42] The Biafra agitators accuse the state and the Federal Republic of Nigeria of marginalising the Igbo people. MASSOB says it is a peaceful group and advertises a 25-stage plan to achieve its goal peacefully.[43] It has two arms of government, the Biafra Government in Exile and the Biafra Shadow Government.[44]

The Nigerian federal government accuses MASSOB of violence; MASSOB's leader, Ralph Uwazuruike, was arrested in 2005 and was detained on treason charges. He has since been released and has been rearrested and released more than five times. In 2009, MASSOB leader Chief Uwazuruike launched an unrecognized "Biafran International Passport" and also launched a Biafra Plate Number in 2016'' in response to persistent demand by some Biafran sympathizers in the diaspora and at home.[45] On 16 June 2012, a Supreme Council of Elders of the Indigenous People of Biafra, another pro-Biafra organization was formed, the body is made up of some prominent persons in Southeastern Nigeria, they sued the Federal Republic of Nigeria for the right to self-determination within their region as a sovereign state, Debe Odumegwu Ojukwu, an eldest son of ex-President / General Ojukwu and a Lagos State based Lawyer was the lead counsel that championed the case.[46]

In 2011, Mr. Nnamdi Kanu made a new plan with his London base staffs and re-opened the Biafra Radio London and in 2012, Mr. Kanu and his staffs moved under the umbrella of Bilie Human Right Initiative (BHRI), which is registered in Nigeria by a London-based barrister, Emeka Emekaesiri whom his term sued Nigeria Government to court on behalf of the Indigenous People of Biafra IPOB under the leadership of Hon. Justice Eze Ozobu OFR; with his Deputy Dr Dozie Ikedife JP, Late Brig.Gen. Joe Achuzia (rtd), secretary. IPOB and its sister organizations, among which are Movement for the Actualisation of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB)'s and the Biafra Nations Youth League, BNYL, have accused the Nigerian Army and the police of extrajudicial killings of their members.

The Nigerian Government, through its broadcasting regulators, the Broadcasting Organisation of Nigerian (BON) and Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), has sought to clamp down on the UK-based station with limited success. On 17 November 2015, the Abia state police command seized an IPOB radio transmitter in Umuahia.[47][48] Kanu was detained by the federal government and released on 24 April 2017. Meanwhile, the group, Biafra Nations Youth League (BNYL) comprising mainly members from the present Southsouth Nigeria especially the Old Cross River region (Now Bakassi, Cross River State, and Akwa Ibom State, (including Igbo members] have organised series of grassroots congress especially in towns such as Ikom, Eket, Bakassi, Itu, Ikwerre, Obudu, Ahoada and other areas of their influence, one of their Leader, Ebuta Ogar Takon, from the Ekoi (also known as Ejagham) ethnic group in Cross River State (also a tribe in Cameroon) disclosed to Nigeria Sun Newspaper that the BNYL struggle for Biafra independence is not limited to the Igbo People cluster of South East Nigeria alone but all inhabitants of the Bight of Biafra in Nigeria. BNYL Leadership said that the neglect of Bakassi refugees and marginalization of the Igbo, Ekoi, Ibibio and other ethnic groups of South Eastern Nigeria are among reasons for Biafra agitation.

The various groups clamoring for the restoration of the independence of Biafra have often been beset with internal wranglings that have impeded its secessionist efforts. On 19 October 2015, Chief Ralph Uwazuruike of the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) disclosed that the director of Radio Biafra and leader of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) under RBL, Nnamdi Kanu, does not belong to the movement and was sacked for indiscipline and for inciting violence among members. In 2016, another MASSOB director of information Mr. Uchenna Madu was expelled from MASSOB for misconduct and inciting violence, Mr Madu is now leading another faction of MASSOB. In 2017, MASSOB launched another radio station named Voice Of Biafra International, and also re-branded MASSOB with the name, Biafra Independent Movement (BIM) in order to illustrate his commitment on his nonviolent declaration since 1999.

BNYL has continued to distance itself from the internal wrangling between MASSOB and IPOB, although Princewill Chimezie Richard (also nicknamed 'Obuka'), National Leader of BNYL, as reported by the New Telegraph Nigeria, announced the group withdrawal from a Coalition of Pro Biafra Groups, following the union announcement declaring the IPOB Leader, Nnamdi Kanu overall leader of the Biafran struggle. This he said was done without due consultations and consideration of other groups opinions. He was arrested and rearrested in Bakassi Peninsula following two attempts to mobilize the BNYL faithful for a protest in support of Biafra.[49][50]

There have been several protests from many Biafra groups, and intense agitation for Biafran secession. Since August 1999, protests have erupted in cities across Nigeria's south-east. Though peaceful, the protesters have been routinely attacked by the Nigerian police and army, with scores of people reportedly killed. Many others have been injured and/or arrested.[51] On 23 December 2015, the federal government charged Nnamdi Kanu with treasonable felony in the Federal High Court in Abuja.[52]

According to the South-East Based Coalition of Human Rights Organizations (SBCHROs), security forces under the directive of the federal government has killed 80 members of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and their supporters between 30 August 2015 and 9 February 2016 in a renewed clampdown on the movement .[53]

A report by Amnesty International also accuses the Nigerian military of killing at least 17 unarmed Biafran separatists in the city of Onitsha prior to a march on 30 May 2016 commemorating the 49th anniversary of the initial secession of Biafra.[54]

Historical maps

Early modern maps of Africa from the 15th–19th centuries, drawn by European cartographers from accounts written by explorers and travellers, reveal some information about Biafra:

- The original word used by the European travellers was not Biafra but Biafara,[55][56] Biafar[57] and sometimes also Biafares.[58]

Senegambia 1707

Senegambia 1707 - According to the maps, the European travellers used the word Biafara to describe the region of today's West Cameroon and Eastern Nigeria including an area around Equatorial Guinea. The German publisher Johann Heinrich Zedler, in his encyclopedia of 1731, published the exact geographical location of the capital of Biafara, namely alongside the river Rio dos Camaroes underneath 6 degrees 10 min. latitude.[59] The words Biafara and Biafares also appear on maps from the 18th century in the area around Senegal and Gambia.[60]

French map of the Gulf of Guinea from 1849

French map of the Gulf of Guinea from 1849

See also

References

- ↑ "Biafra | secessionist state, Nigeria". Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ↑ "Biafra Free State". www.africafederation.net. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- 1 2 Nowa Omoigui. "Federal Nigerian Army Blunders of the Nigerian Civil War – Part 2". Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ↑ McCormack, Fergus (4 December 2016). "Would You Believe? Flights of Angels". RTÉ Press Centre. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ↑ "The Forgotten War". 8 (3). History Ireland Magazine. Autumn 2000. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ↑ Barnaby Philips (13 January 2000). "Biafra: Thirty years on". BBC News. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ↑ "Biafada: A language of Guinea-Bissau".

- ↑ "The Joshua Project: Biafada, Biafar of Guinea-Bissau".

- ↑ "Africa Focus: Ethiopia Minor and a geographical account of the Province of Sierra Leone : (c. 1615): Contents".

- ↑ "Manuel Álvares, Chapter 13: The Biafar Heathen".

- 1 2 Barnaby Philips (13 January 2000). "Biafra: Thirty years on". The BBC. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ↑ Nowa Omoigui. "OPERATION 'AURE': The Northern Military Counter-Rebellion of July 1966". Nigeria/Africa Masterweb.

- ↑ Willy Bozimo. "Festus Samuel Okotie Eboh (1912–1966)". Niger Delta Congress. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ "1966 Coup: The last of the plotters dies". OnlineNigeria.com. 20 March 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Biafran Secession: Nigeria 1967–1970". Armed Conflict Events Database. 16 December 2000.

- ↑ "Ojukwu's Declaration of Biafra Speech". Citizens for Nigeria. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ↑ "Biafra Spotlight - Republic of Biafra is Born". Library of Congress Africa Pamphlet Collection - Flickr. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ↑ "ICE Case Studies". American University. November 1997.

- ↑ Nowa Omoigui (3 October 2007). "Nigerian Civil War file". BBC. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- ↑ "On This Day (30 June)". BBC. 30 June 1969. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ↑ "C. Odumegwu Ojukwu". Wikipedia. 2017-07-28.

- ↑ "Nigeria buries ex-Biafra leader". BBC News. 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ↑ Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 762. ISBN 0-313-32384-4.

- ↑ "Nigeria". Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ Ònyémà Nwázùé. "INTRODUCTION TO THE IGBO LANGUAGE". Archived from the original on 18 August 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Symes, Peter (1997). "The Bank Notes of Biafra". International Bank Note Society Journal. 36 (4). Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ Ivwurie, Dafe (25 February 2011). "Nigeria: The Men Who May Be President (1)". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ "Operation Biafra Babies". Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ↑ "The Last Adventurer" by Steiner, Rolf (Boston:, Little, Brown 1978)

- 1 2 Jowett, Philip (2016). Modern African Wars (5): The Nigerian-Biafran War 1967-70. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Press. ISBN 978-1472816092.

- ↑ Air Enthusiast No. 65 September–October 1996 pp 40–47 article by Vidal, Joao M. Texans in Biafra T-6Gs in use in the Nigerian Civil War

- ↑ "Founding of MSF". Doctors without borders. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Bortolotti, Dan (2004). Hope in Hell: Inside the World of Doctors Without Borders, Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55297-865-6.

- ↑ "World Health Organization" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ↑ "Site cidi.org". Iys.cidi.org. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ "Emerging Genocide in Nigeria". Cwis.org. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ "Chronicles of brutality in Nigeria 2000–2006". Cwis.org. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ Hult, Martin; Tornhammar, Per; Ueda, Peter; Chima, Charles; Edstedt Bonamy, Anna-Karin; Ozumba, Benjamin; Norman, Mikael (2010). "Hypertension, Diabetes and Overweight: Looming Legacies of the Biafran Famine, PLoS ONE". PLoS ONE. Plosone.org. 5 (10): e13582. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013582. PMID 21042579. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ "Nigeria: Those Born During Biafra Famine Are Susceptible to Obesity, Study Finds". The New York Times. 2 November 2010.

- ↑ Akresh, Richard; Bhalotra, Sonia; Leone, Marinella; Osili, Una O. (August 2017). "First and Second Generation Impacts of the Biafran War". NBER Working Paper No. 23721. doi:10.3386/w23721.

- ↑ [punchng.com/kanu-ipob-supporters-fraudsters-says-uwazuruike/ Uwazuruike Reveal why he sacked Kanu from MASSOB] Check

|url=value (help). 11 January 2017. pp. 29–29. - ↑ Senan Murray (3 May 2007). "Reopening Nigeria's civil war wounds". BBC. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ↑ Estelle Shirbon (12 July 2006). "Dream of free Biafra revives in southeast Nigeria". Reuters.

- ↑ "Biafra News – 04.13.2009". Biafra.cwis.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ "MASSOB launches "Biafran Int'l Passport" to celebrate 10th anniversary". Vanguardngr.com. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ "Court determines suit between Nigeria, Biafra on Sept 22". sunnewsonline.com. 18 July 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ↑ "PUO REPORTS - Nigerian Online News Portal". www.puoreports.com. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ↑ "Radio Biafra Container With Massive Transmitter Found In Nnamdi Kanu's Village - NewsRescue.com".

- ↑ "Confusion, as MASSOB disowns Radio Biafra boss, Nnamdi Kanu - Vanguard News". 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Arrested Radio Biafra boss is not our member – MASSOB leader, Uwazuruike". 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Half a century after the war, angry Biafrans are agitating again". The Economist. 28 November 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ↑ "FG Files Fresh Treason Charges against Nnamdi Kanu" Archived 24 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Biafra will not stand, Buhari vows - Vanguard News". 6 March 2016.

- ↑ "Amnesty accuses Nigerian army of killing at least 17 unarmed Biafran separatists".

- ↑ "Map of Africa from 1669". USA: Afriterra Foundation, The Cartographic Free Library. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ "Map of Africa from 1669" (zoom). USA: Afriterra Foundation, The Cartographic Free Library. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ "Map of West Africa from 1729". USA: University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ "Map of North-West Africa, 1829". USA: University of Texas Libraries. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ Zedler, Johann Heinrich. "Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon aller Wissenchafften und Künste". Bavarian State Library. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

page 1684

- ↑ "1730 map - L'Isle, Guillaume de, 1675-1726". Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Library. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Biafra. |