Italian Ethiopia

.svg.png)

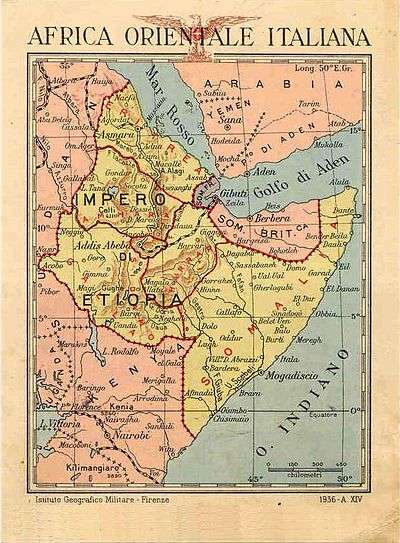

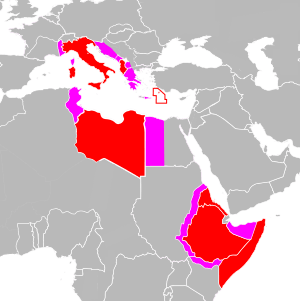

Ethiopia was occupied by Italy in 1936 and became a part of the Italian colony Italian East Africa, during which time Emperor Haile Selassie continued to reign as monarch in exile. Italian Ethiopia was proclaimed in 1936 following the second Italo-Ethiopian War, with Victor Emmanuel III proclaiming himself Emperor of Ethiopia. The occupation lasted until the end of 1941 when Ethiopia was liberated from Italian control by a combination of Ethiopian, British, Commonwealth, Free French, and Free Belgian forces.

Characteristics

Since May 1936 Italian Ethiopia was part of the newly created Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI), or Italian East Africa, and administratively was made of four governorates: Governorate of Amara, Governorate of Harrar, Governorate of Galla-Sidamo and Governorate of Shewa. Each Governorate was under the authority of an Italian governor, answerable to the Italian viceroy, who represented the Emperor Victor Emmanuel The territory around the capital was renamed in 1939 Governorate of Scioa: originally it was called "Governorato di Addis Abeba", but in 1939 the name was changed to show the region of Scioa around the area of Addis Abeba. This was done because areas of the nearby governorates of Harrar, Gallo-Sidamo and Amhara were included in it. Italian Ethiopia had an area of 305,000 square miles and a population of 9,450,000 inhabitants, resulting in a density of 31 per square mile[1]

| Governorate | Italian name | Capital | Total population | Italians[2] | Car Tag | Coat of Arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amhara Governorate | Amara | Gondar | 2,000,000 | 11,103 | AM | |

| Harrar Governorate | Harar | Harrar | 1,600,000 | 10,035 | HA | |

| Galla-Sidamo Governorate | Galla e Sidama | Jimma/Gimma | 4,000,000 | 11,823 | GS | |

| Shewa Governorate | Scioa | Addis Abeba | 1,850,000 | 40,698 | SC | |

Some territories of the defeated Kingdom of Ethiopia were added to Italian Eritrea and Italian Somalia inside AOI, because mainly populated by Eritrean and Somalian populations (but even as a reward to their colonial soldiers who fought in the Italian Army against the Negus troops).

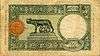

The currency used was the Italian East African lira: the Lira AOI was a special banknote (of 50 lire and 100 lire) circulating in AOI between 1938 [3] and 1941:

| Frontal Image | Back Image | Amount | Color | Frontal Description | Back Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

50 Lire | Green | LIRE CINQVANTA - BANCA D'ITALIA | 50 LIRE - Lupa romana |

|

|

100 Lire | Green/gray | LIRE CENTO - BANCA D'ITALIA - Dea Roma | LIRE CENTO - BANCA D'ITALIA - Aquila |

On 5 May 1936 the capital Addis Ababa was captured by the Italians: on 22 May three new stamps showing the King of Italy were issued. Four further values inscribed "ETIOPIA" were issued on 5 December 1936. After that date, the stamps were issued with the name "Africa Orientale Italiana" on it.[4]

History (1936–1941)

Emperor Haile Selassie's reign was interrupted in 1935 when Italian forces invaded and occupied Ethiopia.

The Italian army, under the direction of dictator Benito Mussolini, invaded Ethiopian territory on October 2, 1935. One of the first actions done by the Italians was to proclaim the abolition of slavery for the 9 million slaves in all Ethiopia[5]. They occupied the capital Addis Ababa on May 5. Emperor Haile Selassie pleaded to the League of Nations for aid in resisting the Italians. Nevertheless, the country was formally annexed on May 9, 1936 and the Emperor went into exile.

The war was full of cruelty: the Ethiopians used Dum-dum bullets (prohibited by the Hague Convention of 1899, Declaration IV,3) and the Italians used gas (prohibited under the Geneva Protocol of 1922).[6] Many Ethiopians died in the invasion. The Negus claimed that more than 275,000 Ethiopian fighters were killed compared to only 1,537 Italians, while the Italian authorities estimated that 16,000 Ethiopians and 2,700 Italians (including Italian colonial troops) died in battle.[7]

Italy in late 1936 requested the "League of Nations" to recognize the annexation of Ethiopia: all member nations (including Britain and France), with the exception of the Soviet Union, voted to support it. The King of Italy (Victor Emmanuel III) was crowned Emperor of Ethiopia and the Italians created an Italian empire in Africa (Italian East Africa) with Ethiopia, Eritrea and Italian Somalia. In 1937 Mussolini boasted that, with his conquest of Ethiopia, "finally Adua was avenged" and that he had abolished slavery in Ethiopia.[8]

Some Ethiopians welcomed the Italians and collaborated with them in the government of the newly created Impero italiano, like Ras Sejum Mangascià, Ras Ghetacciù Abaté and Ras Kebbedé Guebret. In 1937 the friendship of Sejum Mangascia with the Italian Viceroy Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta enabled this Ras to play an influential role in securing the release of 3,000 Ethiopian POWs being held in Italian Somaliland.

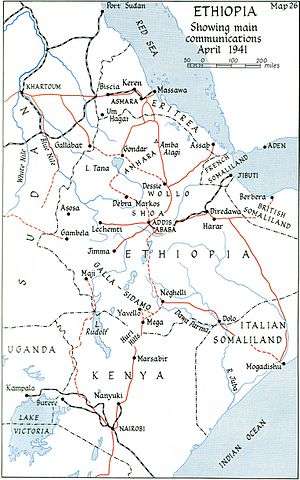

The Italians invested substantively in Ethiopian infrastructure development. They created the "imperial road" between Addis Abeba and Massaua, the Addis Abeba - Mogadishu and the Addis Abeba - Assab.[9] the Italians built more than 4,500 km of roads linking the country beyond 900 km of railways were reconstructed or initiated (like the railway between Addis Abeba and Assab), dams and hydroelectric plants were built, and many public and private companies were established in the underdeveloped country. The most important were: "Compagnie per il cotone d'Etiopia" (Cotton industry); "Cementerie d'Etiopia" (Cement industry); "Compagnia etiopica mineraria" (Minerals industry); "Imprese elettriche d'Etiopia" (Electricity industry); "Compagnia etiopica degli esplosivi" (Armament industry); "Trasporti automobilistici (Citao)" (Mechanic & Transport industry).

Italians even created new airports and in 1936 started the worldwide famous Linea dell'Impero, a flight connecting Addis Abeba to Rome. The line was opened after the Italian conquest of Ethiopia and was followed by the first air links with the Italian colonies in Italian East Africa, which began in a pioneering way since 1934. The route was enlarged to 6,379 km and initially joined Rome with Addis Ababa via Syracuse, Benghazi, Cairo, Wadi Halfa, Khartoum, Kassala, Asmara, Dire Dawa.[10] There was a change of aircraft in Benghazi (or sometimes in Tripoli). The route was carried out in three and a half days of daytime flight and the frequency was four flights per week in both directions. Later from Addis Ababa there were three flights a week that continued to Mogadishu, capital of Italian Somalia.

The most important railway line in the African colonies of the Kingdom of Italy, the Djibouti-Addis Ababa long 784 km, was acquired following the conquest of the Ethiopian Empire by the Italians in 1936. The route was served until 1935 by steam trains that took about 36 hours to do the total trip between the capital of Ethiopia and the port of Djibouti. Following the Italian conquest was obtained in 1938 the increase of speed for the trains with the introduction of four railcars high capacity "type 038" derived from the model Fiat ALn56.[11]

These diesel trains were able to reach 70 km/h and so the time travel was cut in half to just 18 hours: they were used until the mid 1960s.[12] At the main stations there were some bus connections to the other cities of Italian Ethiopia not served by the railway.[13] Additionally, near the Addis Ababa station was created a special unit against fire, that was the only one in all Africa.[14]

In 1936, during the occupation of Ethiopia, the Italians considered the construction of new railway routes from Addis-Ababa running as follows: Addis-Ababa, Dessie, Adigrat, Massawa: covering 1000 km; Addis-Ababa, Dessie, Assab - Dessie, Gondar, Om, Ager; Addis-Ababa, Megheli, Dollo, Mogadishu. All these projects had to be abandoned due to war operations.

— Jean Pierre Crozet

Projects of connecting to the Eritrean railway network did not found practical realization in 1939. In the same year was studied the possibility of connecting the Ethiopian station of Dire-Dawa to the port of Assab in southern Eritrea, in order to bypass the French Somaliland. Until 1938 there was a protective military unit in the trains, because of the Ethiopian guerrilla in the area (that by the beginning of World War II faded away).[15]

The Italians not only made new roads & other structural improvements, but they also greatly improved the socio-economical conditions of the native population, as the same emperor Haile Selassie recognized when back in power after 1941.

Indeed much of these improvements were part of a plan to bring half a million Italians to colonize the Ethiopian plateaus. In October 1939 the Italian colonists in Ethiopia were 35,441, of whom 30,232 male (85.3%) and 5,209 female (14.7%), most of them living in urban areas.[16] Only 3,200 Italian farmers moved to colonize farm areas, mostly around the capital and in the Scioa Governorate, where they were under sporadic attack by pro-Haile Selassie guerrillas until 1939.

However the Ethiopian guerrilla -that in late 1939 was still controlling nearly 1/4 of Ethiopia highlands (but that has never been active in the areas of Ethiopia united to Eritrea and Somalia in 1936)- was present at the beginning of World War II only in the Harar and Galla-Sidamo Governorate: according to the viceroy Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta the guerrilla was going to disappear in 2 years more (like has happened in Cyrenaica in the early 1930s). Indeed Abebe Aregai, the last leader of the "Arbegnocks" (as were called the guerrilla fighters in Ethiopia) after the 1939 surrender of Ethiopian leaders Zaudiè Asfau and Olonà Dinkel, was doing a surrender proposal with the Italians in spring 1940.

In early 1940, also as a consequence of the guerrilla nearly disappearance, Italian Ethiopia was enjoying a small "boom" of economic & social development with the commerce and industrial sector greatly improving in the capital and in the main cities.

A remarkable effort was made to improve healthcare in Ethiopia: beside the doctors belonging to the Italian Africa Health Corps, flanked by 450 military doctors, there were about 500 civilian doctors (232 specialists, among whom 30 pediatricians, and 262 general practitioners). Special maternity wards were built in the hospitals situated in the main locations. The new Italian hospital in Addis Ababa had a delivery room and a pediatric clinic, with a capacity of over 100 beds in its various sections: expectant mothers, postpartum mothers, babies’ room, gynecological ward, infectious diseases, visitors’ room, etc. The children’s hospital was subdivided into separate wards for babies and older children, for infectious, gastro-intestinal or pulmonary diseases, etc. Moreover, a university-type faculty was founded in 1941 in Asmara to train nurses....Social life in Addis Ababa (and Asmara) was pulsating just like that of any other European town. At the heart of the city were the markets: in the capital (Addis Abeba) in 1939 over 75,000 heads of cattle had been slaughtered and thousands of tons of foodstuffs had been sold. Dozens of shops and even department stores were opened in both cities. Leisure activities also boomed: in Addis Ababa four cinemas had been built...New dancehalls, restaurants and bars were being opened everywhere. The working men’s clubs and numerous sports and recreational societies, supported by local government and by the PNF, organised the colonists’ (and native Etiopians) free time.

— G. Podesta[17]

During the five years of Italian rule also the Catholicism grew in importance, thanks mainly to the efforts of missionaries like Elisa Angela Meneguzzi (she became known as the "Ecumenical Fire" due to her strong efforts at ecumenism with Coptic Christians and Muslims while also catering to the latter two and their relations with the Catholics of Dire Dawa[18]).

During World War II, in the summer of 1940 Italian armed forces successfully invaded all of British Somaliland.[19] But, by spring of 1941, the British had counter-attacked and pushed deep into Italian East Africa. By 5 May, Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia had returned to Addis Ababa to reclaim his throne. In November, the last organised Italian resistance in Ethiopia ended with the fall of Gondar.[20] However, following the surrender of East Africa, some Italians conducted a guerrilla war which lasted for two more years.

This guerrilla was done primarily by military units with Italian officers (like Captain Paolo Aloisi, Captain Leopoldo Rizzo, Blackshirt officer De Varda and Major Lucchetti) but also by civilians like Rosa Dainelli. She was a doctor who in August 1942 succeeded in entering the main ammunition depot of the British army in Addis Abeba, and blowing it up, miraculously survived the huge explosion. Her sabotage destroyed the ammunition for the new British Sten sub machine gun, delaying the use of this "state of the art" armament for many months[21]. Her true name was Danielli Rosa and the date of attack was September 15, 1941.[22]

In February 1947 Italy officially renounced to all the colonies in the World War II Peace Treaty, ending 12 years of involvement in Ethiopia's politics since 1935. Italy agreed to:

- Recognition of the independence of Ethiopia

- Pay War reparation of $25,000,000 US to Ethiopia

- Accept "Annex XI of the Treaty", upon the recommendation of the United Nations General Assembly in Resolution 390, that indicated that Eritrea was to be federated with Ethiopia.

See also

- Italian East Africa topics

- Italians of Ethiopia

- Italian Eritrea

- Italian Somalia

- Linea dell'Impero

- Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta

Notes

- ↑ Royal Institute of International Affairs (24 August 1940). "Italian Possessions in Africa: II. Italian East Africa". Bulletin of International News. 17 (17): 1065–1074.

- ↑ Istat Statistiche 2010

- ↑ Bank of Italy

- ↑ Postage stamps of Italian Ethiopia

- ↑ Slavery abolition by the Italians

- ↑ Antonicelli, Franco. Trent'anni di storia italiana 1915 - 1945, p. 79.

- ↑ Antonicelli, Franco. Trent'anni di storia italiana 1915 - 1945, p. 133.

- ↑ Del Boca, Angelo. Italiani in Africa Orientale: La conquista dell'Impero, p.131.

- ↑ 1940 Article on the special road Addis Abeba-Assab and map (in Italian)

- ↑ Treccani: Via dell'Impero (in Italian)

- ↑ Fiat ALn56 "Littorina"

- ↑ Image of a Fiat ALn56 in 1964 Addis Abeba station

- ↑ Dire Dawa bus connection to Harrar

- ↑ "Pompieri ad Addis Abeba" (in Italian)

- ↑ Photo of Italian soldiers defending the ethiopian railway trains

- ↑ Italian emigration in Etiopia (in Italian)

- ↑ Podesta: "Family and Society in Italian Africa"

- ↑ Blessed Elisa Angela Meneguzzi

- ↑ Dickson (2001) p.103

- ↑ Jowett (2001) p.7

- ↑ Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale. pag. 103

- ↑ Di Lalla, Fabrizio, “Sotto due bandiere. Lotta di liberazione etiopica e resistenza italiana in Africa Orientale”. p. 235

Bibliography

- Italian: Inventario dell'Archivio Storico del Ministero Africa Italiana (PDF) (in Italian), 1: (1857-1939), Rome, Italy: Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Italy), 1975, retrieved 2017-12-20

- Bandini, Franco (1971). Gli italiani in Africa: Storia delle guerre coloniali 1882-1943 (in Italian). Milan, Italy: Longanesi. OCLC 1253348.

- Beltrami, Vanni (2013). Italia d'Oltremare: Storie dei territori italiani dalla conquista alla caduta (in Italian). Rome Italy: Edizioni Nuova Cultura. p. 273. ISBN 978-88-6134-702-1. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- Dickson, Keith (2001). World War II for Dummies. Hoboken, New Jersey, US: Wiley. ISBN 9780764553523.

- Jowett, Philip S (2001). The Italian Army 1940–45 2: Africa 1940–43. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781855328655.

- Sbiacchi, Alberto (April 1979). "Hailé Selassié and the Italians, 1941-43". African Studies Review. African Studies Association. XXII (1).