Italian East Africa

| Italian East Africa Africa Orientale Italiana Talyaaniga Bariga Afrika شرق افريقيا الايطالية | |

|---|---|

| 1936–1941 | |

.svg.png) Flag

Coat of arms

| |

|

Anthem: "Royal March of Ordinance" | |

.svg.png) | |

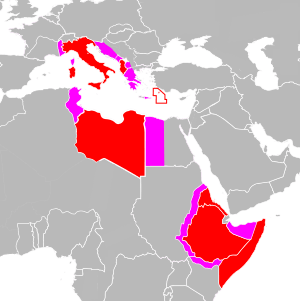

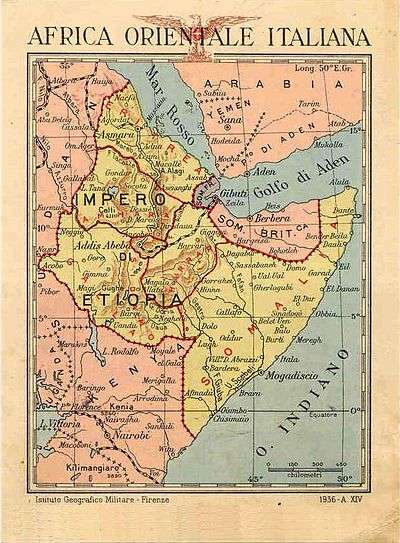

Italian East Africa in 1936.

| |

| Status | Colony of Italy |

| Capital | Addis Ababa |

| Common languages | Italian, Arabic, Oromo, Amharic, Tigrinya, Somali, Tigre |

| Emperor | |

• 1936–1941 | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Viceroya | |

• 1936 | Pietro Badoglio |

• 1936–1937 | Rodolfo Graziani |

• 1937–1941 | Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta |

• 1941 | Pietro Gazzera |

• 1941 | Guglielmo Nasi |

| Historical era | Interwar period / WWII |

• Established | 15 January 1936 |

• Disestablished | 1 July 1941 |

| Area | |

| 1939[1] | 1,725,000 km2 (666,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1939[1] | 12100000 |

| Currency | Italian East African lira |

| Today part of |

|

Italian East Africa (Italian: Africa Orientale Italiana) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somaliland, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire which became Italian Ethiopia.[3]

During the Second World War, Italian East Africa was occupied by a British-led force including colonial and Ethiopian units.[4] After the war, Italian Somaliland and Eritrea came under British administration, while Ethiopia regained full independence. In 1949, Italian Somaliland was reconstituted as the Trust Territory of Somaliland, which was administered by Italy from 1950 until its independence in 1960.

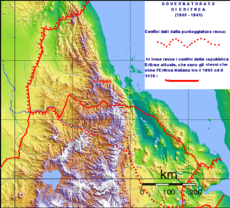

Territory

When established in 1936, Italian East Africa (the other Italian colony in Africa being Italian North Africa) consisted of the old Italian possessions in the Horn of Africa, Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, and the recently annexed Empire of Ethiopia.[5] Victor Emmanuel III of Italy consequently adopted the title of "Emperor of Ethiopia", although having not been recognized by any country other than Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. The territory was divided into the six governorates of Italian East Africa: Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, plus four provinces of Ethiopia (Amhara, Galla-Sidamo, Scioa, Harar) each under the authority of an Italian governor, answerable to a viceroy, who in turn represented the Emperor.

Italian East Africa was briefly enlarged in 1940, as Italian forces conquered British Somaliland, thereby bringing all Somali territories under Italian administration. However, the enlarged colony was dismembered only a year later, when in the course of the East African Campaign the colony was occupied by British forces.

Italian East Africa, in Italian "Africa Orientale Italiana", was acronymed in official documents as "AOI".[5]

History

The dominion was formed in 1936, after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War that resulted in the annexation of the Ethiopian Empire by Fascist Italy, by merging the pre-existing colonies of Italian Somaliland and Italian Eritrea with the newly conquered territory.

Conquest of Ethiopia

Historians are still divided about the reasons for the Italian attack on Ethiopia in 1935. Some Italian historians such as Franco Catalano and Giorgio Rochat argue that the invasion was an act of social imperialism, contending that the Great Depression had badly damaged Mussolini's prestige, and that he needed a foreign war to distract public opinion.[6] Other historians such as Pietro Pastorelli have argued that the invasion was launched as part of an expansionist program to make Italy the main power in the Red Sea area and the Middle East.[6] A middle way interpretation was offered by the American historian MacGregor Knox, who argued that the war was started for both foreign and domestic reasons, being both a part of Mussolini's long-range expansionist plans and intended to give Mussolini a foreign policy triumph that would allow him to push the Fascist system in a more radical direction at home.[6]

Unlike forty years earlier, Italy's forces were far superior to the Abyssinian forces, especially in air power, and they were soon victorious. Emperor Haile Selassie was forced to flee the country, with Italian forces entering the capital city, Addis Ababa, to proclaim an empire by May 1936, making Ethiopia part of Italian East Africa.[7]

The Italian victory in the war coincided with the zenith of the international popularity of dictator Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime, during which colonialist leaders praised Mussolini for his actions.[8] Mussolini's international popularity decreased as he endorsed the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, beginning a political tilt toward Germany that eventually led to the downfall of Mussolini and the Fascist regime in Italy in World War II.[9]

Second World War and dissolution

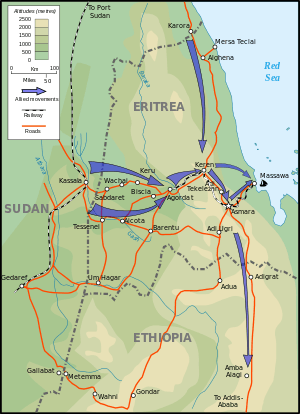

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on Britain and France, which made Italian military forces in Libya a threat to Egypt and those in the Italian East Africa a danger to the British and French territories in the Horn of Africa. Italian belligerence also closed the Mediterranean to Allied merchant ships and endangered British supply routes along the coast of East Africa, the Gulf of Aden, Red Sea and the Suez Canal. (The Kingdom of Egypt remained neutral during World War II, but the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 allowed the British to occupy Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.)[10] Egypt, the Suez Canal, French Somaliland and British Somaliland were also vulnerable to invasion, but the Comando Supremo (Italian General Staff) had planned for a war after 1942. In the summer of 1940, Italy was far from ready for a long war or for the occupation of large areas of Africa.[11]

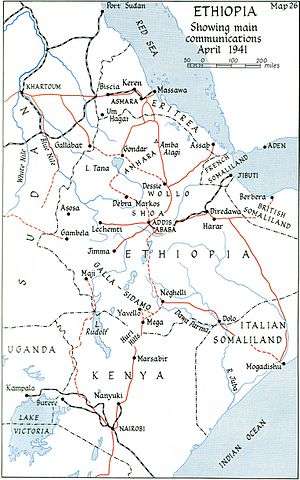

Hostilities began on 13 June 1940, with an Italian air raid on the base of 1 Squadron Southern Rhodesian Air Force (237 (Rhodesia) Squadron RAF) at Wajir in the East Africa Protectorate (Kenya). In August 1940, the protectorate of British Somaliland was occupied by Italian forces and absorbed into Italian East Africa. This occupation lasted around six months. By early 1941, Italian forces had been largely pushed back from Kenya and Sudan. On 6 April 1941, Addis Ababa was occupied by the 11th (African) Division, which received the surrender of the city.[12] The remnants of the Italian forces in the AOI surrendered after the Battle of Gondar in November 1941, except for groups that fought an Italian guerrilla war in Ethiopia against the British until the Armistice of Cassibile (3 September 1943) ended hostilities between Italy and the Allies.

In January 1942, with the final official surrender of the Italians, the British, under American pressure, signed an interim Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement with Selassie, acknowledging Ethiopian sovereignty. Makonnen Endelkachew was named as Prime Minister and on 19 December 1944, the final Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement was signed. Eritrea was placed under British military administration for the duration, and in 1950, it became part of Ethiopia. After 1945, Britain controlled both Somalilands, as protectorates. In November 1949, during the Potsdam Conference, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland under close supervision, on condition that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.[13] British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland, the Trust Territory of Somalia (ex-Italian Somaliland) became independent on 1 July 1960 and the territories united as the Somali Republic.[14]

Colonial administration

The colony was administered by a Viceroy of Ethiopia and Governor General of Italian East Africa, appointed by the Italian monarch. The dominion was further divided for administrative purposes into six Governorates and forty Commissionerships.

Economic development

Fascist colonial policy in Italian East Africa had a divide and conquer characteristic.

In order to weaken the Orthodox Christian Amhara people who had run Ethiopia in the past, territory claimed by Eritrean Tigray-Tigrinyas and Somalis was given to the Eritrea Governorate and Somalia Governorate.[15] Reconstruction efforts after the war in 1936 were partially focused on benefiting the Muslim peoples in the colony at the expense of the Amhara to strengthen support by Muslims for the Italian colony.[15]

Italy's Fascist regime encouraged Italian peasants to colonize Ethiopia by setting up farms and small manufacturing businesses.[15] However, few Italians came to the Ethiopian colony, with most going to Eritrea and Somalia. While Italian Eritrea enjoyed some degree of development, supported by nearly 80,000 Italian colonists,[16] by 1940 only 3,200 farmers had arrived in Ethiopia, less than ten percent of the Fascist regime's goal.[17] Continued insurgency by native Ethiopians, lack of natural resources, rough terrain, and uncertainty of political and military conditions discouraged development and settlement in the countryside.[17]

The Italians invested substantively in Ethiopian infrastructure development. They created the "imperial road" between Addis Abeba and Massaua, the Addis Abeba - Mogadishu and the Addis Abeba - Assab.[18] 900 km of railways were reconstructed or initiated (like the railway between Addis Abeba and Assab), dams and hydroelectric plants were built, and many public and private companies were established in the underdeveloped country. The most important were: "Compagnie per il cotone d'Etiopia" (Cotton industry); "Cementerie d'Etiopia" (Cement industry); "Compagnia etiopica mineraria" (Minerals industry); "Imprese elettriche d'Etiopia" (Electricity industry); "Compagnia etiopica degli esplosivi" (Armament industry); "Trasporti automobilistici (Citao)" (Mechanic & Transport industry).

Italians even created new airports and in 1936 started the worldwide famous Linea dell'Impero, a flight connecting Addis Abeba to Rome. The line was opened after the Italian conquest of Ethiopia and was followed by the first air links with the Italian colonies in Africa Orientale Italiana (Italian East Africa), which began in a pioneering way since 1934. The route was enlarged to 6,379 km and initially joined Rome with Addis Ababa via Syracuse, Benghazi, Cairo, Wadi Halfa, Khartoum, Kassala, Asmara, Dire Dawa.[19] There was a change of aircraft in Benghazi (or sometimes in Tripoli). The route was carried out in three and a half days of daytime flight and the frequency was four flights per week in both directions. Later from Addis Ababa there were three flights a week that continued to Mogadishu, capital of Italian Somalia.

The most important railway line in the African colonies of the Kingdom of Italy, the Djibouti-Addis Ababa long 784 km, was acquired following the conquest of the Ethiopian Empire by the Italians in 1936. The route was served until 1935 by steam trains that took about 36 hours to do the total trip between the capital of Ethiopia and the port of Djibouti. Following the Italian conquest was obtained in 1938 the increase of speed for the trains with the introduction of four railcars high capacity "type 038" derived from the model Fiat ALn56.[20]

These diesel trains were able to reach 70 km/h and so the time travel was cut in half to just 18 hours: they were used until the mid 1960s.[21] At the main stations there were some bus connections to the other cities of Italian Ethiopia not served by the railway.[22] Additionally, near the Addis Ababa station was created a special unit against fire, that was the only one in all Africa.[23]

However Ethiopia and Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI) proved to be extremely expensive to maintain, as the budget for the fiscal year 1936-37 had been set at 19.136 billion lira to create the necessary infrastructure for the colony.[15] At the time, Italy's entire yearly revenue was only 18.581 billion lira.[15]

The architects of the Fascist regime had drafted grandiose urbanistic projects for the enlargement of Addis Ababa, in order to build a state-of-the-art capital of the Africa Orientale Italiana, but these architectural plans -like all the other developments- were stopped by World War II.[24]

Demographics

In 1939, there were 165,267 Italian citizens in the Italian East Africa, the majority of them concentrated around the main urban centres of Asmara, Addis Ababa and Mogadishu. The total population was estimated around 12.1 million, with a density of just over 6.9 inhabitants per square kilometre (18/sq mi). The distribution of population was, however, very uneven. Eritrea, with an area of 230,000 km2 (90,000 sq mi), had a population estimated in about 1.5 million, with a population density of 6.4/km2 (16.7/sq mi); Ethiopia with an area of 790,000 km2 (305,000 sq mi) and a population of some 9.5 million, had a resulting density of 12/km2 (31/sq mi); sparsely populated Italian Somaliland finally, with an area of 700,000 km2 (271,000 sq mi) and a population of just 1.1 million, had a very low density of 1.5/km2 (4/sq mi).[25]

| English | Italian | Capital | Total population[1] | Italians[1] | Tag | Coat of Arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amhara Governorate | Amara | Gondar | 2,000,000 | 11,103 | AM | |

| Eritrea Governorate | Eritrea | Asmara | 1,500,000 | 72,408 | ER | |

| Harrar Governorate | Harar | Harrar | 1,600,000 | 10,035 | HA | |

| Galla-Sidamo Governorate | Galla e Sidama | Jimma/Gimma | 4,000,000 | 11,823 | GS | |

| Shewa Governorate | Scioà | Addis Abeba | 1,850,000 | 40,698 | SC | |

| Somalia Governorate | Somalia | Mogadishu | 1,150,000 | 19,200 | SOM |

Atrocities against the Ethiopian population

In February 1937, following an assassination attempt on Italian East Africa's Viceroy, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, Italian soldiers raided the famous Ethiopian monastery Debre Libanos, where the plotters had taken refuge, and executed the monks and nuns.[15] Afterwards, Italian soldiers destroyed native settlements in Addis Ababa, which resulted in 30,000 Ethiopians being killed and their homes left burned to the ground.[15][26] The brutal massacre has come to be known as Yekatit 12.

After the massacres, Graziani became known as "the Butcher of Ethiopia".[27] He was subsequently removed by Mussolini and replaced by Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, who followed a more conciliatory policy towards the natives, obtaining a limited success in pacifying Ethiopia.[28]

See also

- Colonial heads of Italian East Africa

- Italian Governors of Addis Ababa

- Italian Governors of Amhara

- Italian Governors of Galla-Sidamo

- Italian Governors of Harar

- Italian Governors of Scioa

- Dubats

- Political history of Eastern Africa

- Italian Ethiopia

- Italians of Ethiopia

- Italian guerrilla war in Ethiopia

- Italian Africa Police

- Italian East African lira

- Augusto Turati

- Languages of Africa

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Istat (December 2010). "I censimenti nell'Italia unita I censimenti nell'Italia unita Le fonti di stato della popolazione tra il XIX e il XXI secolo ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DI STATISTICA SOCIETÀ ITALIANA DI DEMOGRAFIA STORICA Le fonti di stato della popolazione tra il XIX e il XXI secolo" (PDF). Annali di Statistica. XII. 2: 263. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ Melvin E. Page;Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia -page 1054

- ↑ "Italian East Africa". World Statesmen. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, Thomas P. "Ethiopia in World War II". A Country Study: Ethiopia. Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- 1 2 Ben-Ghiat, edited by Ruth; Fuller, Mia (2008). Italian colonialism (1st pbk. ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0230606369.

- 1 2 3 Kallis, Aristotle Fascist Ideology, London: Routledge, 2000 page 124.

- ↑ "Ethiopia 1935–36". icrc.org. 8 January 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006.

- ↑ Baer, p. 279

- ↑ Italian Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918–1940. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, pp. 6–7, 69.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, pp. 38–40.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, pp. 421–422.

- ↑ Zolberg, Aguayo & Suhrke 1992, p. 106.

- ↑ NEB 2002, p. 835.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cannistraro, p. 5

- ↑ Italian industries and companies in Eritrea Archived 2009-04-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Cannistraro, p. 6

- ↑ "1940 Article on the special road Addis Abeba-Assab and map (in Italian)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ↑ Treccani: Via dell'Impero (in Italian)

- ↑ Fiat ALn56 "Littorina"

- ↑ Image of a Fiat ALn56 in 1964 Addis Abeba station

- ↑ Dire Dawa bus connection to Harrar

- ↑ "Pompieri ad Addis Abeba" (in Italian)

- ↑ Addis Abeba 1939 Urbanistic and Architectural Plan Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Royal Institute of International Affairs (24 August 1940). "Italian Possessions in Africa: II. Italian East Africa". Bulletin of International News. 17 (17): 1065–1074.

- ↑ Sarti, p. 191

- ↑ Mockler, Anthony (2003). "4". Haile Selassie's War. New York: Olive Branch.

- ↑ Knox, MacGregor (1986). Mussolini unleashed, 1939-1941 : politics and strategy in fascist Italy's last war (1st pbk. ed.). Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 9780521338356.

Bibliography

- Antonicelli, Franco (1961) Trent'anni di storia italiana 1915 - 1945, Saggi series 295, Torino : Einaudi, 387 p. [in Italian]

- Brioni, Simone and Shimelis Bonsa Gulema, eds. (2017) The Horn of Africa and Italy: Colonial, Postcolonial and Transnational Cultural Encounters, Oxford : Peter Lang, ISBN 978-1-78707-993-9

- Cannistraro, Philip V. (1982) Historical Dictionary of Fascist Italy, Westport, Conn.; London : Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-21317-8

- Del Boca, Angelo (1986) Italiani in Africa Orientale: La caduta dell'Impero, Biblioteca universale Laterza 186, Roma : Laterza, ISBN 88-420-2810-X [in Italian]

- Mockler, Anthony (1984). Haile Selassie's War: The Italian-Ethiopian Campaign, 1935-1941, New York : Random House, ISBN 0-394-54222-3

- Sarti, Roland (1974) The Ax Within: Italian fascism in action, New York : New Viewpoints, ISBN 0-531-06498-0

- Mauri, Arnaldo (1967). Il mercato del credito in Etiopia, Milano, Giuffrè, pp. XVI, 504 [in Italian].

- Calchi Novati, Gian Carlo (2011).L'Africa d'Italia, Carrocci, Roma. [in Italian]

- Tuccimei, Ercole (1999). La Banca d'Italia in Africa, Presentazione di Arnaldo Mauri, Laterza, Bari, ISBN 88-420-5686-3 [in Italian]

External links

- Italian East African Armed Forces, 10 June 1940

- 1940 Colonial Brigade, 10 June 1940

- Italian East Africa Air Command, 10 June 1940

- Ascari: I Leoni di Eritrea/Ascari: The Eritrean Lions. Second Italo-abyssinian war. Eritrea colonial history, Eritrean ascari pictures/photos galleries and videos, historical atlas...

- Geographic map of Italian business community in Africa (December 2012) , established using applied onomastics.