Third Rome

Third Rome is the hypothetical successor to the legacy of ancient Rome (the "first Rome"). Second Rome usually refers to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, unofficially called "New Rome", or one of the claimed successors to the Western Roman Empire such as the Papal States and the Holy Roman Empire.[2]

Successor to Byzantium

Russian claims

Known as a theological and a political concept "Moscow is the Third Rome", it was formulated in the 15th–16th centuries in the Grand Duchy of Moscow.[3] In the concept there could be traced three interrelated and interpenetrating fields of ideas: a) theology that is linked with justification of necessity and inevitability in unity of Eastern Orthodox Church; b) social politics that are derived out of the feeling of unity in East Slavic territories being historically tied through Christian Orthodox faith and Slavic culture; c) state doctrine, according to which the Moscow Prince should act as a supreme sovereign (Sovereign and legislator) of Christian Orthodox nations and become a defender of the Christian Orthodox Church. Herewith the Church should facilitate the Sovereign in execution of his function supposedly determined by God, the autocratic administration.[3]

After the fall of Tǎrnovo to the Ottoman Turks in 1393, a number of Bulgarian clergymen sought shelter in the Russian lands and transferred the idea of the Third Rome there, which eventually resurfaced in Tver, during the reign of Boris of Tver, when the monk Foma (Thomas) of Tver had written The Eulogy of the Pious Grand Prince Boris Alexandrovich in 1453.[4][5]

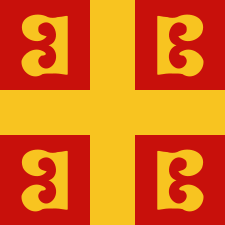

Within decades after the capture of Constantinople by Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire on 29 May 1453, some Eastern Orthodox people were nominating Moscow as the "Third Rome", or the "New Rome".[6] Stirrings of this sentiment began during the reign of Ivan III of Russia who had married Sophia Paleologue. Sophia was a niece of Constantine XI, the last Byzantine emperor. By the rules and laws of inheritance followed by most European monarchies of the time, Ivan could claim that he and his offspring were heirs of the fallen Empire, but the Roman traditions of the empire had never recognized automatic inheritance of the Imperial office.[7]. It is also important to note that she was not the heiress of the Byzantine throne: her brother, Andreas Palaiologos, in fact had the rights of succession to the Byzantine throne. Andreas died in 1502, having sold his titles and royal and imperial rights to Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. This would mean that, in a purely legal sense, the Russian tsars were never entitled to the Byzantine throne. A stronger claim was based on religious symbolism. The Orthodox faith was central to Byzantine notions of their identity and what distinguished them from "barbarians". Vladimir the Great had converted Kievan Rus' to Orthodoxy in 988, in return for which he became the first barbarian to ever get an Imperial princess as a wife.

The idea of Muscovy as heir to Rome crystallized with a panegyric letter composed by the Russian monk Philotheus (Filofey) of Pskov in 1510 to their son Grand Duke Vasili III,[3] which proclaimed, "Two Romes have fallen. The third stands. And there will be no fourth. No one shall replace your Christian Tsardom!" Contrary to the common misconception, Filofey[8] explicitly identifies Third Rome with Muscovy (the country) rather than with Moscow (the city), although the term "Muscovy" was considered synonymous with the Russian lands at the time. Somewhat notably, Moscow is placed on seven hills, as were Rome and Constantinople.

The whole idea could be traced as early as 1492 when Metropolitan of Moscow Zosimus expressed it in a foreword to his work of 1492 "Presentation of the Paschalion" (Russian: "Изложение Пасхалии").[3]

Shortly before Joseph II inherited the States of the House of Austria, he traveled to Russia in 1780. In her conversations with him Catherine II made it clear that she would renew the Byzantine empire and to use her one-year-old grandson Konstantin as Emperor of Constantinople. The guest tried to suggest to the guest that he could be held harmless in the Papal States.[9]

Anatolian Seljuk claims

The Sultanate of Rûm established in the parts of Anatolia which had been conquered from the Byzantine Empire by the Seljuk Empire.

The name Rûm is the Arabic name of Rome and the Roman Empire, الرُّومُ ar-Rūm, a loan from Greek Ρωμιοί "Romans".[10]

Ottoman claims

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD, Mehmed II declared himself Kayser-i Rum, literally "Caesar of Rome".[11] The claim was recognized by the Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople, but not by Roman Catholic Western Europe. Gennadios (Georgios Scholarios), a staunch enemy of the West, had been enthroned Patriarch of Constantinople with all the ceremonial attributes of Byzantium by Mehmed himself acting as Roman Emperor and in turn Gennadios recognized Mehmed as successor to the throne.[12] Mehmed's claim rested with the concept that Constantinople was the seat of the Roman Empire, after the transfer of its capital to Constantinople in 330 AD and the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Mehmed also had a blood lineage to the Byzantine Imperial family; his predecessor, Sultan Orhan I had married a Byzantine princess, and Mehmed may have claimed descent from John Tzelepes Komnenos.[13] During that period the Ottoman Empire also destroyed Otranto and its people, and Mehmed II was planning on taking Rome itself when the Italian campaign was cut short by his sudden death.[14] The title fell into disuse after his death, but the imperial bodies created by Mehmed II lived on for centuries to come.

Greek claims

The term appeared for the first time during the debates of Prime Minister Ioannis Kolettis with King Otto that preceded the promulgation of the 1844 constitution.[15] This was a visionary nationalist aspiration that was to dominate foreign relations and, to a significant extent, determine domestic politics of the Greek state for much of the first century of independence. The expression was new in 1844 but the concept had roots in the Greek popular psyche. It long had hopes of liberation from Turkish rule and restoration of the Byzantine Empire.[15]

Πάλι με χρόνια με καιρούς,

- πάλι δικά μας θα 'ναι!

(Once more, as years and time go by, once more they shall be ours).[16]

The Megali Idea implied the goal of reviving the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would be, as ancient geographer Strabo wrote, a Greek world encompassing mostly the former Byzantine lands from the Ionian Sea to the west, to Asia Minor and the Black Sea to the east and from Thrace, Macedonia and Epirus to the north, to Crete and Cyprus to the south. This new state would have Constantinople as its capital: it would be the "Greece of Two Continents and Five Seas" (Europe and Asia, the Ionian, Aegean, Marmara, Black and Libyan seas, respectively).

Albanian claims

The Principality of Kastrioti took a flag showing a double-headed eagle, an ancient symbol used by various cultures of Balkans (especially the Byzantine Empire)[21][22][23], which later became the Albanian flag.

For Skanderbegs military victories, he received the title Arnavutlu İskender Bey, (Albanian: Skënderbe shqiptari, English: Lord Alexander, the Albanian) comparing Kastrioti's military brilliance to that of Alexander the Great.

Bulgarian claims

In 913, Simeon I of Bulgaria was crowned Emperor (Tsar) by the Patriarch of Constantinople and imperial regent Nicholas Mystikos outside of the Byzantine capital. In its final simplified form, the title read "Emperor and Autocrat of all Bulgarians and Romans" (Tsar i samodarzhets na vsichki balgari i gartsi in the modern vernacular). The Roman component in the Bulgarian imperial title indicated both rulership over Greek speakers and the derivation of the imperial tradition from the Romans, however this component was never recognised by the Byzantine court.

Byzantine recognition of Simeon's imperial title was revoked by the succeeding Byzantine government. The decade 914–924 was spent in destructive warfare between Byzantium and Bulgaria over this and other matters of conflict. The Bulgarian monarch, who had further irritated his Byzantine counterpart by claiming the title "Emperor of the Romans" (basileus tōn Rōmaiōn), was eventually recognized, as "Emperor of the Bulgarians" (basileus tōn Boulgarōn) by the Byzantine Emperor Romanos I Lakapenos in 924. Byzantine recognition of the imperial dignity of the Bulgarian monarch and the patriarchal dignity of the Bulgarian patriarch was again confirmed at the conclusion of permanent peace and a Bulgarian–Byzantine dynastic marriage in 927. In the meantime, the Bulgarian imperial title may have been also confirmed by the pope. The Bulgarian imperial title "tsar" was adopted by all Bulgarian monarchs up to the fall of Bulgaria under Ottoman rule. 14th-century Bulgarian literary compositions clearly denote the Bulgarian capital (Tarnovo) as a successor of Rome and Constantinople, in effect, the "Third Rome".

Serbian claims

In 1345, the Serbian King Stefan Uroš IV Dušan proclaimed himself Emperor (Tsar) and was crowned as such at Skopje on Easter 1346 by the newly created Serbian Patriarch, and by the Patriarch of Bulgaria and the autocephalous Archbishop of Ohrid. His imperial title was recognized by Bulgaria and various other neighbors and trading partners but not by the Byzantine Empire. In its final simplified form, the Serbian imperial title read "Emperor of Serbs and Greeks" (цар Срба и Грка in modern Serbian). It was only employed by Stefan Uroš IV Dušan and his son Stefan Uroš V in Serbia (until his death in 1371), after which it became extinct. A half-brother of Dušan, Simeon Uroš, and then his son Jovan Uroš, claimed the same title, until the latter's abdication in 1373, while ruling as dynasts in Thessaly. The "Greek" component in the Serbian imperial title indicates both rulership over Greeks and the derivation of the imperial tradition from the Romans.

Spanish claims

The last Eastern Roman Emperor Andreas Palaiologos ceded the Roman Imperial crown to Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile in his last will dated April 7th, 1502.[24] Many cities and institutions in the Kingdom of Spain to this day use the double-headed Roman eagle. The city of Toledo, province of Toledo and the province of Zamora are just few of many examples.

Latin Empire

The Latin Empire (official Empire of Romania) was a Crusader state founded after the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to supplant the Byzantine Empire as the titular Roman Empire in the east, with a Western Roman Catholic emperor enthroned in place of the Eastern Orthodox Roman emperors. James of Baux willed his titular claims to Duke Louis I of Anjou, also claimant to the throne of Naples, but Louis and his descendants (including the Holy Roman Emperor from the House of Habsburg-Lorraine and the Austrian emperors through Francis I) never used the title.

Successor to the Holy Roman Empire

.svg.png)

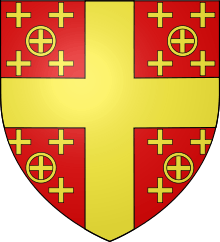

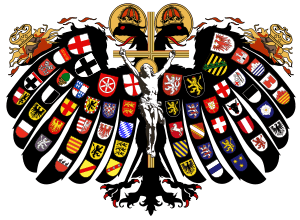

The Carolingian Empire has been claimed to have deliberately sought to revive the Roman Empire in the West.[25] According to early German nationalism, the Carolingian Empire transformed into the Holy Roman Empire as a continuation of the Western Roman Empire.[25] In 800, the title of Emperor of the Romans was granted to Charlemagne by Pope Leo III. The word "holy" (often retroactively applied to all emperors since Charlemagne) was added under the reign of emperor Frederick I Barbarossa in 1157.[26]

German claims

Later the German Empire in 1871 also claimed to be the Third Rome, also through lineage of the HRE.[27][28] The title for emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, the Austrian Empire and the German Empire was Kaiser (derived from Latin Caesar), the German word for emperor.

Claims by the German Empire of 1871 to 1918 of being a "Third Rome" have been criticized because the German Empire was led by a Protestant ruler and no concordat had been achieved with the Catholic Church (that was a major basis of the continuation of Roman culture in the West).[29]

Nazi Germany used the term Drittes Reich (meaning "Third Realm" or "Third Empire"), as successor of the first realm (HRE) and the second realm (the German Empire). In 1939, however, in a circular not intended for publication, further use of the term "Third Reich" was prohibited.[30]

Austrian claims

.svg.png)

After the Holy Roman Empire was dismantled in 1806, the Austrian Empire sought to lay claim as the heir of the Holy Roman Empire as Austria's Habsburgs attempted to unite Germany under their rule.[25]

The Federal State of Austria used some symbols from the Holy Roman Empire and the Austrian Empire:

The Cross potent, symbol of the Fatherland Front, was as medieval symbol - the oldest representation is on the (German) Imperial Sword (one of the four most important parts of the Imperial Regalia of the HRE). The consistent use of this propaganda symbol was new to Austria.

In contrast to the one-headed, graphically strictly designed eagle of the German Reich, the eagle of the estates state leaned against the two-headed Quaternionenadler of the Holy Roman Empire. Since Old Austria had led the double eagle for centuries, since the Habsburgs became Holy Roman Emperor, the return to it seemed nostalgic. The traditional care with elements of imperial Austria, the admission of aristocratic titles and the partial reversal of the Habsburg Law fit in with this.

The Austrian Armed Forces received in 1934 (with the exception of the small air forces) instead of the previously worn comparatively modern uniforms in the style of the Reichswehr such in the manner of the Danube monarchy.

French claims

In four campaigns, Napoleon transformed his "Carolingian" feudal and federal empire into one modelled on the Roman Empire. The memories of imperial Rome were for a third time, after Julius Caesar and Charlemagne, used to modify the historical evolution of France. Though the vague plan for an invasion of Great Britain was never executed, the Battle of Ulm and the Battle of Austerlitz overshadowed the defeat of Trafalgar, and the camp at Boulogne put at Napoleon's disposal the best military resources he had commanded, in the form of La Grande Armée.

When Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor of France, he also called his own imperial crown the "Crown of Charlemagne".

Desperate for money, Andreas Palaiologos sold the rights to the Byzantine crown which he possessed since the death of his father. Charles VIII of France purchased the rights of succession from Andreas during 1494 and died on April 7, 1498.[31] The following Kings of France continued the claim and used the Imperial titles and honors: Louis XII, Francis I, Henry II and Francis II. Not until Charles IX in 1566 did the imperial claim come to an eventual end through the rules of extinctive prescription as a direct result of desuetude or lack of use. Charles IX wrote that the imperial Byzantine title "is not more eminent than that of king, which sounds better and sweeter."[32]

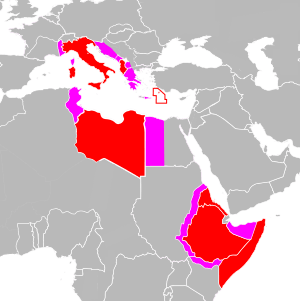

Italy as the Third Rome

In Italy, the concept of a "Third Rome" is related to the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, created in 1861, and the current Italian Republic, created in 1946.

Risorgimento

.svg.png)

Giuseppe Mazzini, Italian nationalist and patriot, promoted the notion of the "Third Rome" during the Risorgimento. He said, "After the Rome of the emperors, after the Rome of the Popes, there will come the Rome of the people", addressing Italian unification and the establishment of Rome as the capital.[33] After the unification of Italy into the Kingdom of Italy, the state was referred to as the Third Rome by Italian figures.[34]

After the unification, Mazzini spoke of the need of Italy as a Third Rome to have imperial aspirations.[35] Mazzini said that Italy should "invade and colonize Tunisian lands" as it was the "key to the Central Mediterranean", and he viewed Italy as having the right to dominate the Mediterranean Sea as ancient Rome had done.[35]

Fascist Empire

In his speeches, Italian leader Benito Mussolini referred to his Fascist Italy as a "Third Rome" or as a New Roman Empire.[36] Terza Roma (Third Rome; the Fascist Rome after the Imperial and the Papal ones) was also a name for Mussolini's plan to expand Rome towards Ostia and the sea. The EUR neighbourhood was the first step in that direction.[37]

The European Union as Third Rome

Although the European Union has never officially claimed to be the resurrection of the Roman Empire, it has a substantial cultural, geographical and historical claim. Greco-Roman culture was spread throughout Europe during the Empire and has laid the foundation of European civilisation,[38] and as such, Roman laws, philosophy and cultural institutions have largely survived in Europe and the territories that make up the European Union, whereas they have been close to completely lost in the non-European parts of the Empire post the Islamic Expansion.[39] With the spread of Latin Christendom, the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire, and the survival of the Byzantine Empire and the Roman Catholic Church, the Roman identity was never completely lost, but transformed into a Christian Identity, as Europe became synonymous with the Land of Christendom during the Carolingian Renaissance[40]. As Greco-Roman culture was imitated and consciously resurrected during the Italian Renaissance of the 14th century, this Christian identity lost its emphasis on religion and gained focus on shared linguistic, historic and cultural origins, transforming into the European Identity. These three identities (Roman, Christian and European) are ultimately based on a sense of belonging to European Civilisation, and as such, one can claim that the European identity is a modern version of the Roman, making a union of Europeans a modern version of Rome.

Continuity of European civilisation and unity

Greco-Minoan civilisation

European civilisation started in Crete as the Minoans created the first European high culture in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC[41]. The Minoans remained the only high culture in Europe for over 1000 years, and spread their civilisation throughout the Aegean world, most notably to the Mycenaean Greeks, who had settled on the Greek mainland. By the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, the Mycenaeans had become heavily "Minoanised" and made large parts of Minoan culture their own, including art, writing system, architecture and religion[42]. After the Mycenaean conquest of Crete and remaining Minoan territories, these two cultures merged into a single Greco-minoan culture. This culture was largely lost in the Bronze Age collapse, after which the Greek Dark Ages ensued.[43]

Greco-Roman civilization

In the early 9th century BC, the Greeks embarked on a conscious effort to restore their former grandeur and sophistication, leading to the Greek Renaissance ca. 900-600 BC and revival of Greco-Minoan culture. This period is followed by Classical Antiquity, during which the Greeks established the intellectual core of European civilization. They spent most of this time disunited, with the most powerful Greek states, Athens, Sparta and Thebes, competed for hegemony. However, they did unite for short periods, most notably during the Persian wars and under Phillip the Great of Macedonia. More importantly, they had an extremely strong in-out-group mentality with regards to their culture, considering the peoples of Asia alien degenerates,[44] and viewing the non-hellenized peoples in Europe as barbarians. As such, even though political unity was mostly absent during this time, Greek (and thus European) civilization was viewed as something very distinct from other peoples.

As the Greek influence grew, much of European Mediterranean was colonized and Hellenized. This included modern Italy from Sicily to Naples (founded by the Greeks as Neapolis). In particular, the Latin people and the City-state of Rome was Hellenized to an extent where they adopted Greek philosophy, architecture, writing system and religion and made it their own, much like the Greeks had adopted the Minoan culture. As the Romans expanded their power and conquered all of Southern and most of Western and Central Europe, these regions were Romanized, many of them to an extent that they adopted the Roman identity, Latin as their primary language (e.g. all of France and Iberia), and as Rome converted to Christendom, so did all of Roman Europe. As the West Roman Empire collapsed in 476 AD,[45] Roman civilization in Western Europe was severely damaged.

The Holy Roman Empire and the modern era

In the 8th century, the Franks, with the support of the Catholic Church, had established an Empire that comprised most of Western Europe. As Charlemagne (German: Karl der Große) inherited the Frankish realm, he expanded it to all of Central and Western Europe except the southern tip of Italy and Iberia, and proclaimed the Roman Empire (calling it the Holy Roman Empire) to have been reestablished,[46] and was crowned as Roman Emperor by the Pope in Rome. During his reign, he launched an enormous project to resurrect Roman culture, copying the former Empire's organisational, education and legal systems, art, and classical literature. This is today known as the Carolingian Renaissance, and its main instrument was the Catholic church, the only Roman institution that had survived the collapse, and preserved major elements of Greco-Roman thought, philosophy, science and administration. This, combined with the influence of the Eastern Roman Empire over eastern Europe and the spread of Orthodox Christendom, led to the subsequent European renaissances (i.e. the Ottoian, 12th century and in particular the Italian Renaissance from the 14th to 17th centuries), which transferred Roman culture to modern era Europe.

The most successful effort of any Holy Roman Emperor to ever fully revive the West Roman Empire was arguably made by Emperor Charles V of Hapsburg, who at the height of his power ruled all of Spain, half of Italy, the Netherlands, Alsace and Lorraine, Austria and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.[47] He had the ambition to unite all the Lands of Christendom, but had to abdicate due to religious tension within the Empire, debt in Spain and humiliating loss of Imperial territory to France. The Holy Roman Empire survived as a super-national institution until 1806, when it was conquered by Napoleon,[48] and saw itself as the legitimate heir of Rome and uniter of the Lands of Christendom during most if not all of its existence. After this, Napoleon laid his own claim to having resurrected the Roman Empire, as he had united not only the regions of Charlemagne's Empire, but also Italy and Spain, giving him control of close to all of the West Roman Empire. In 1804 he crowned himself Emperor in the presence of the Pope in Paris, adopted the Roman eagle as his standard and proclaimed the following in 1812:[49]

“I am a true Roman Emperor; I am of the best race of the Caesars – those who are founders.”

Since Napoleon's final defeat and the dissolution of his empire in 1815, no European ruler has claimed to revive the Roman Empire. The 19th century did, however, see the birth of the first pan-European movements, calling for a united Europe. This idea was popular among intellectuals, and the term "United States of Europe" became widespread, perhaps most famously used be Victor Hugo during his speech at the International Peace Conference 1847:[50]

"A day will come when all nations on our continent will form a European brotherhood ... A day will come when we shall see ... the United States of America and the United States of Europe face to face, reaching out for each other across the seas."

During the second world war, Nazi Germany did subjugate France and the Netherlands, giving it political control over much of Charlemagne's original empire, however, it saw itself as an entirely German entity with no pan-European identity. It considered itself as the Third German Reich, with the Holy Roman Empire being the first and Imperial Germany being the second, its symbolism was modeled on pre-Romanised pagan Germanic culture, using runes and other pagan symbols in its iconography, and its ultimate goal was to expand ethnic Germany, exterminating other European peoples (especially to the east), as opposed to uniting European civilisation.

After the war, France launched a European unification project with itself at its core, starting with the Coal and Steel union, followed by the European Community, and finally the European Union. As such, throughout all of European history, there has powerful driving force for political unity. A similar phenomenon can be found at the other side of the Eurasian continent in China, although this driving force has arguably been much stronger than the European equivalent for the past 2000 years. [51]

Historic Symbolism used by the European Union

Europa and the Bull

The European Union uses a variety of symbols from Greco-Roman culture. In its official buildings are statues of the Goddess Europa and the bull, taken from ancient Crete. In Greek mythology, Zeus transforms himself into a bull, and carries Europa to Crete, where they have the son Minos, who is the first ruler of Crete. This is hence a reference not only to the Hellenic religion practiced by both the Greeks, the Romans, and the peoples they brought into European civilisation, but also to the Minoans, and it represents the ancient Greeks' understanding and veneration of where their culture comes from. This bull can further be seen on the Residence Permit of all non-European residing within the Union[52].

Charlemagne

Since 2008, the European Parliament, together with the city of Aachen (which was Charlemagne's capital city), hands out Charlemagne's Youth Price to a young European who has done a great service to European Unity. This is a recognition of Charlemagne's contribution to resurrecting European civilisation in Western Europe and his ambition for European unity. Perhaps it is also a recognition of the fact that the Holy Roman Empire laid the institutional groundwork for the Union, as it too was an entity above ethnic groups that provided political alignment and collective protection for a range of different European peoples[53].

In popular culture

The concept of a "Third Rome" figures greatly in the second memoir of Whittaker Chambers. Although published posthumously as Cold Friday (1964), Chambers had planned it from inception as "The Third Rome". A long chapter called "The Third Rome" appears in the memoir.[54][55][56]

In the 1997 film, The Saint, the villain, Russian oil magnate Ivan Tretiak, publishes a book titled The Third Rome.

Third Rome is also a DLC for Europa Universalis IV, a grand strategy history game adding features for the Russians.

See also

References

- ↑ Koon, Tracy H. (1985). Believe, Obey, Fight: Political Socialization of Youth in Fascist Italy, 1922-1943. UNC Press Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8078-1652-3. Extract of page 20

- ↑ https://www.rbth.com/arts/history/2017/03/30/why-do-russians-call-moscow-the-third-rome_730921

- 1 2 3 4 Mashkov, A.D. Moscow is the Third Rome (МОСКВА – ТРЕТІЙ РИМ). Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Robert Auty, Dimitri Obolensky (Ed.), An Introduction to Russian Language and Literature, p. 94, Cambridge University Press 1997, ISBN 0-521-20894-7

- ↑ Alar Laats, The concept of the Third Rome and its political implications, p. 102

- ↑ Parry, Ken; Melling, David, eds. (1999). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 490. ISBN 0-631-23203-6.

- ↑ Nicol, Donald MacGillivray, Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453, Cambridge University Press, Second Edition, 1993, p. 72

- ↑ Filofey

- ↑ Derek Beales: Joseph II, Band 1, Cambridge 1987, p. 431–438.

- ↑ Alexander Kazhdan, "Rūm" The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press, 1991), vol. 3, p. 1816. Paul Wittek, Rise of the Ottoman Empire, Royal Asiatic Society Books, Routledge (2013), p. 81: "This state too bore the name of Rûm, if not officially, then at least in everyday usage, and its princes appear in the Eastern chronicles under the name 'Seljuks of Rûm' (Ar.: Salâjika ar-Rûm). A. Christian Van Gorder, Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-muslims in Iran p. 215: "The Seljuqs called the lands of their sultanate Rum because it had been established on territory long considered 'Roman', i.e. Byzantine, by Muslim armies."

- ↑ İlber Ortaylı, "Büyük Constantin ve İstanbul", Milliyet, 28 May 2011.

- ↑ Dimitri Kitsikis, Türk-Yunan İmparatorluğu. Arabölge gerçeği ışığında Osmanlı Tarihine bakış – İstanbul, İletişim Yayınları, 1996.

- ↑ Norwich, John Julius (1995). Byzantium:The Decline and Fall. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 81&ndash, 82. ISBN 0-679-41650-1.

- ↑ Bunson, Matthew. "How the 800 Martyrs of Otranto Saved Rome". Catholic Answers. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- 1 2 History of Greece Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ↑ D. Bolukbasi and D. Bölükbaşı, Turkey And Greece: The Aegean Disputes, Routledge Cavendish 2004

- ↑ Hodgkinson 2005, p. xix

- ↑ Machiel Kiel, Ottoman architecture in Albania, 1385-1912, Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture, 1990, ISBN 9290633301, p. 173: The coat of arms of the Kastriot family, a black eagle on a red field, became the flag and the symbol of the little country.

- ↑ Neubecker, Ottfried (1987). The Flags of Albania. The Flag bulletin. 26. Flag Research Center. p. 111. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

History records that the 15th century Albanian national hero, Skanderbeg (i.e. George Kastriota), had raised the red flag with the black eagle over his ancestral home, the Fortress of Kruje

. - ↑ Malltezi, Luan (1987). Studime historike. Akademia e Shkencave, Instituti i Historisë. p. 179.

Dihet se par arsye të njohura historike (për shkak të pushtimit të gjatë osman) asnjë flamur origjinal i Skënderbeut, i përdorur prej tij ne shek. XV, nuk ka mundur të vijë deri ne ditët tona. Megjithatë bu- rimet historike që sinjalizojnë ekzistencën e tyre japin të dhëna më se të mjaftueshme për t'i përfytyruar ata ne mënyrë рак a shumë të saktë. «Skënderbeu — shkruan Barleti — mbante flamurë të kuq të qëndisur me shqiponja të zeza dykrenore. Ky ishte flamuri i fisit të tij.»

- ↑ Elsie 2001, "Eagles", p. 78.

- ↑ Grumeza 2010, p. 99: "During John Hunyadi's campaign at Niss in 1443, Skanderberg and a few hundred Albanians defected from the Turkish ranks; for twenty-five years he scored remarkable victories against the Ottomans. He adopted the Byzantine double-headed eagle flag, and his spectacular victories brought him the papal title Athleta Christi."

- ↑ Mucha, Crampton & Louda 1985, p. 36.

- ↑ Polychrones Kyprianos Enepekides, Das Wiener Testament des Andreas Palaiologos vom 7. April 1502

- 1 2 3 Craig M. White. The Great German Nation: Origins and Destiny. AuthorHouse, 2007. p. 139.

- ↑ Peter Moraw, Heiliges Reich, in: Lexikon des Mittelalters, Munich & Zurich: Artemis 1977–1999, vol. 4, columns 2025–2028.

- ↑ Warwick Ball. Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. London, England, UK: Routledge, 2000. p. 449.

- ↑ Craig M. White. The Great German Nation: Origins and Destiny. AuthorHouse, 2007. p. 169.

- ↑

- ↑ Reinhard Bollmus: Das Amt Rosenberg und seine Gegner. Studien zum Machtkampf im nationalsozialistischen Herrschaftssystem. Stuttgart 1970, S. 236.

- ↑ Norwich, John Julius, Byzantium - The Decline and Fall, p.446

- ↑ David Potter, A History of France, 1460-1560: The Emergence of a Nation State, 1995, p. 33

- ↑ Rome Seminar Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Christopher Duggan. The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796. New York, New York, USA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008. p. 304.

- 1 2 Silvana Patriarca, Lucy Riall. The Risorgimento Revisited: Nationalism and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Italy. p. 248.

- ↑ Martin Clark, Mussolini: Profiles in Power (London: Pearson Longman, 2005), 136.

- ↑ Discorso pronunciato in Campidoglio per l'insediamento del primo Governatore di Roma il 31 dicembre 1925, Internet Archive copy of a page with a Mussolini speech.

- ↑ https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/legal-roman-eagles_how-ancient-rome-influenced-european-law/36688830

- ↑ f

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ http://etc.ancient.eu/interviews/what-caused-the-bronze-age-collapse/

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=-mVFAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA284&lpg=PA284&dq=ancient+greek+asia+degenerate&source=bl&ots=RxC-Jm68Vm&sig=T3Njm0OVqyrYNM0gFC2B0wavjB4&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwij-IvAkcHYAhVC6RQKHarZBOQQ6AEIPjAF#v=onepage&q=ancient%20greek%20asia%20degenerate&f=false

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/fallofrome_article_01.shtml

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charlemagne

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-V-Holy-Roman-emperor

- ↑ http://www.historytoday.com/richard-cavendish/end-holy-roman-empire

- ↑ https://www.warhistoryonline.com/ancient-history/napoleon-as-augustus.html

- ↑ Ideas of European unity before 1945

- ↑ http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/lecture5b.html

- ↑ Third Rome#The Holy Roman Empire and Modern Era

- ↑ Third Rome#The Holy Roman Empire and Modern Era

- ↑ Chambers, Whittaker (1964). Cold Friday. New York: Random House.

- ↑ O’Brien, Conor Cruise (19 November 1964). "The Perjured Saint". The New York Review of Books.

- ↑ Chambers, David (9 July 2011). "Whittaker Chambers (1901–1961): Ghosts and Phantoms". WhittakerChambers.org.

Bibliography

- Chambers, Whittaker (1964). Cold Friday. New York: Random House.

- Dmytryshyn, Basil (transl). 1991. Medieval Russia: A Source Book, 850–1700. 259–261. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Fort Worth, Texas.

- Poe, Marshall. "Moscow, the Third Rome: the Origins and Transformations of a 'Pivotal Moment'." Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas (2001) (In Russian: "Izobretenie kontseptsii "Moskva—Tretii Rim". Ab Imperio. Teoriia i istoriia natsional'nostei i natsionalizma v postsovetskom prostranstve 1: 2 (2000), 61–86.)

- Martin, Janet. 1995. Medieval Russia: 980–1584. 293. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK.

- Stremooukhoff, Dimitri (January 1953). "Moscow The Third Rome: Sources of the Doctrine". Speculum. 84–101.