Islamic Defenders Front

.jpg) Front Pembela Islam (FPI) | |

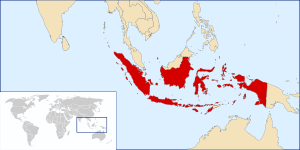

Zone of influence | |

| Formation | 17 August 1998 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Muhammad Rizieq Shihab |

| Type | Sunni Islamist organization |

| Headquarters | Petamburan, West Jakarta |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 6°11′41″S 106°48′29″E / 6.194717°S 106.808158°E |

Region served | Indonesia |

Official language | Indonesian |

Chairman | Ahmad Shabri Lubis |

| Website |

www |

The Islamic Defenders Front (Arabic: الجبهة الدفاعية الإسلامية),[1][2] also known by the acronym FPI (Indonesian: Front Pembela Islam) or Islam Defenders Front, is a far-right Sunni Islamist Indonesian political organization formed in 1998. It was founded by Muhammad Rizieq Shihab with the backing from Indonesian military, police generals and political elites.[3][4] The organization's leader is Ahmad Shabri Lubis who was inaugurated in 2015,[5] and Rizieq Shihab remains acting as the adviser by the title Great Imam of FPI for life.[6]

FPI originally started as a civil vigilante that positioned itself as an Islamic moral police against vice, whose activity was unauthorized by the government. FPI targeted several warungs, stores, bars, nightclubs and entertainment venues which were perceived as discourteous for selling alcohol or open during Ramadhan.[7] Later, it transformed itself into an Islamist pressure group with active online campaigns.[8]

The organization has been known to have organized various religious or political mass protests; the most prominent example being the November 2016 Jakarta protests and several other rallies against the incumbent Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama in the following months. Other prominent protests orchestrated by FPI is a rally in the American Embassy condemning the Iraq War, which dates back as far as late 2003. The protests are criticized as conducting hate crimes in the name of Islam[9][7] and religious-related violence.[10]

History

FPI was founded on 17 August 1998 by Habib Muhammad Rizieq Syihab. Rizieq Shihab is a Hadhrami Arab Indonesian[11][12] of Sufi Sunni Muslim background, who is known for defending Hadhrami Sufi Islam while advocating against Ahmadis and Shias. The establishment received backing from military and police generals, including former Jakarta Police Chief Nugroho Jayusman. It is also associated with former Indonesian National Armed Forces commander Wiranto.[3] Leaked US diplomatic cables obtained through WikiLeaks say that FPI allegedly received funding from the police and former political elites.[4] The organization nominally aims to implement sharia law in Indonesia.[13]

Later, it transformed itself into an Islamist pressure group which furthers their political motives by promoting what is considered as religious or racial propaganda throughout the Internet and occasional anti-government campaigns.[8] However, in January 2017, several FPI's official Twitter accounts were suspended due to violations of Twitter rules, including spamming, incivility and threats.[14]

Protests and actions

Actions against religious pluralism

FPI has been vocal against liberalism and multiculturalism, and to the extension Pancasila doctrine which upholds religious pluralism. On 1 June 2008, FPI staged an attack against members of the National Alliance for the Freedom of Faith and Religion (AKKBB), who were holding a rally coinciding the commemoration day of Pancasila near the Monas monument in the city center. The attack was upheld as a response to the perceived threat by AKKBB against FPI. The incident was referred to by media as Monas Incident. The incident had caused media outrage and lead to the arrest of Rizieq Shihab among 56 other FPI members.[15] Rizieq was later imprisoned for one year and six months, after being convicted over attacks against masses of AKKBB.[7] In January 2017, Police declared FPI leader Rizieq Shihab a suspect for alleged Pancasila defamation.[16]

FPI also often holds protests against what it sees as Christianization of Indonesia. Notable cases include GKI Yasmin Bogor, and HKBP Church Bekasi, where the group used violence to force them to close down their churches.[17][18] FPI also endorsed the Singkil administration for closing around 20 churches in Singkil, Aceh. The Singkil case stirred the controversy for the use of the local administrative law in accordance with Sharia, which runs counter against the Indonesian constitution which guarantees freedom of religious practices.[19] In early 2017, FPI and related Islamist groups staged a mass protest against the construction of a new Christian church in Bekasi, West Java. The protest developed into a riot and scuffle with the police, resulting in several property damages and five police officers left injured.[20]

Actions against Ahmadiyya

One of Rizieq Shihab's propaganda campaign openly called for hostility against Ahmadis:[21]

"We call on the Muslim community. Let us go to war with Ahmadiyyah! Kill Ahmadiyyah wherever they are!........ And, if they talk about human rights? Human rights are satanic! Human rights are crap!.....If they want to know who is responsible for killing Ahmadiyyah, it is I; it is FPI and others from the Muslim community who are responsible for killing Ahmadiyyah! Say that Sobri Lubis ordered it, that Habib Rizieq and FPI ordered it! "

FPI has been suspected acting in the background of the assault of the Ahmadiyya community and killing of three on 6 February in 2011. The assault was led by a group of over thousand people, wielding rocks, machetes, swords, and spears. The group attacked the house of an Ahmadi leader in Cikeusik, Banten.[22] Similarly, a group attacked the Ahmadiyya headquarters near Bogor and harassed its members in areas such as in East Lombok, Manislor, Tasikmalaya, Parung, and Garut.[23]

Actions against perceived communist threat

FPI often employs anti-communism as its political motivation. In June 2010, along with other organizations, FPI attacked a meeting on free healthcare in East Java, mistaking it for a meeting of the banned Communist Party of Indonesia.[24] In January 2017, FPI called for the withdrawal of Rupiah banknotes, accused them of displaying the image of the banned hammer and sickle logo.[25] FPI allegations, however, was rejected by Bank Indonesia (BI), referring to it as a recto-verso security feature of BI logo for the new Rupiah banknotes. FPI was accused of stirring public unrest by slandering Bank Indonesia and the government.[26]

Anti-government campaigns and relations with opposition parties

The FPI has been vocal in campaigns against the incumbent governments, starting in President Yudhoyono's presidency. The campaign is said to be more intense during the Joko Widodo era and after Basuki Tjahaja Purnama's alleged blasphemy case in 2016. Because of this, the FPI is widely seen as an opposition movement, and is reportedly known to have close relations with opposition coalition parties. Various FPI leaders and senior cadres recently developed closer ties with numerous opposition figures.

Actions against perceived defamation of Islamic sensitivity

FPI had been sensitive toward the perceived defamation and violation of Islamic norms in various aspects of society. In its early days, FPI had targeted shops at Garut and Makassar that sold alcohol during Ramadan month, some of which were reportedly ransacked.[27] Various nightclubs, bars, and cafes have been also targeted by FPI for perceived unconformity with the Islamic norms.[28] In 2006, FPI and other Islamic organizations including Indonesian Mujahedeen Council had protested against the issue of Playboy Indonesia. The protest had led to the eviction of the Playboy office from Jakarta to Bali.[29] In 2013, FPI accused LGBT activists, such as Lady Gaga[30] and Irshad Manji,[31] of being "devils", and threatened their safety. This had erupted controversy in 2013 during the Lady Gaga's Born This Way tour,[30] which resulted in the eventual cancellation of concerts in Indonesia. The action was criticized for being a violation of Indonesian law sanctioning violent threat, as prescribed in Kitab Undang-Undang Pidana, article 336.[32]

In 2015, FPI lambasted the Regent of Purwakarta Dedi Mulyadi, accusing him as a musyrik (polytheist) after he put up statues of Sundanese puppet characters in a number of city parks throughout Purwakarta in West Java. FPI considered Dedi of debasing Islamic tenets by violating the aniconist principle of Islam, as well as using the Sundanese greeting Sampurasun, instead of the Muslim-approved Assalamualaikum. In December 2015, around a hundred FPI members conducted sweeping against the Regent. Its members inspected cars passing through the front gate of Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) in Central Jakarta where the Indonesia Theater Federation Award was being held, attempting to stop Dedi from attending the event.[33]

Opposition and uprising against Basuki Tjahaja Purnama

FPI had been known for its constant efforts to topple the administration of Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, popularly known as Ahok. FPI had criticized Basuki's background as a Christian and Chinese Indonesian, both being the minority, citing that the position of the governor of Jakarta should be reserved only for Muslims.[8] In 2014, FPI held a demonstration in front of Jakarta DPRD Building. FPI refused Basuki to become Jakarta's governor after being left by Joko Widodo who was elected as President in the same year.[7]

In late 2016, during the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election season, FPI led the national outrage against Basuki for his alleged blasphemy against the Qur'an. As a response to the perceived blasphemy, FPI had made seven protests titled "Aksi Bela Islam[34]", (Indonesian for "Action for Defending Islam") in order to create a pressure against Basuki and demanded for his imprisonment. The protests were culminated in November 2016 Jakarta protests, December 2016 Jakarta protests and February 2017 Jakarta protests. They were done once a month until Basuki's final conviction on May 2017, in which he was sentenced to two years.

Receptions

General public

There have been calls by Indonesians, mainly mainstream Muslims, other religious organizations, political communities and ethnic groups, FPI to be disbanded or banned.[35][36] Various critics and media outlets have described FPI as inciting extremism, racism and bigotry, particularly noting its occasional hate crimes, discrimination against minority and religious intolerance.[10][37] International Crisis Report called it "an urban thug organization", emphasizing on their violent vigilantism.[3][13] The group has been also criticized for the use of violence; the police have recorded that FPI engaged in 29 cases of violence and destructive behaviour in 2010 and 5 cases in 2011 in the following provinces: West Java, Banten Province, Central Java, North Sumatra and South Sumatra.[38]

Rejection in Kalimantan

On February 11, 2012 hundreds of protesters from the local community in Palangkaraya, Central Kalimantan; mainly from the Dayak tribe; staged a protest at the Tjilik Riwut Airport to block the arrival of four senior leaders of the group, who wanted to inaugurate the provincial branch of the organization. Due to security concerns, the management of the airport ordered all FPI members to remain on board of the aircraft while other passengers disembarked. FPI members were then flown to Banjarmasin in South Kalimantan. The deputy chairman of the Central Kalimantan Dayak Tribe Council (DAD) later said that the organization had asked the Central Kalimantan Police to ban the group's provincial chapter as FPI's presence would create tension, particularly as Central Kalimantan is known as a place conducive to religious harmony.[39] A formal letter from the Central Kalimantan administration stated that they firmly rejected FPI and would not let them establish a chapter in the province because it "contradicts the local wisdom of the Dayak tribe that upholds peace". The letter was sent to the Minister of Coordination of Political, Legal and Security Affairs with copies being sent to the President of Indonesia, the People's Consultative Assembly Chief, the Speaker of the House, the Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court, the Home Minister and the National Police Chief. Up till now, FPI has been banned all over the Kalimantan Region by Kalimantan's people for their disruptive and divisive actions against their communities.[40]

References

- ↑ Front Pembela Islam (Islamic Defenders Front -- FPI. Terrorism Research & Analysis Consortium.

- ↑ Kassam, Nisan. Indonesia: The Islamic Defenders Front. Human Rights Without Frontiers.

- 1 2 3 "Indonesia: Implications of the Ahmadiyah Decree" (PDF). International Crisis Group Update Briefing. Jakarta/Brussels: International Crisis Group (78). 7 July 2008. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- 1 2 "WikiLeaks: National Police funded FPI hard-liners". September 5, 2011.

- ↑ Ini Ketua Umu FPI Yang Baru Ust. Ahmad. Muslimedia News. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ↑ "Gelar Imam Besar hingga Capres 2014 untuk Habib Rizieq". Merdeka. August 24, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 M Andika Putra; Raja Eben Lumbanrau (17 January 2017). "Jejak FPI dan Status 'Napi' Rizieq Shihab". CNN Indonesia (in Indonesian).

- 1 2 3 Sita W. Dewi (September 25, 2014). "FPI threatens Chinese Indonesians". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- ↑ Frost, Frank; Rann, Ann; Chin, Andrew. "Terrorism in Southeast Asia". Parliament of Australia, Parliamentary Library. Archived from the original on 2010-03-28. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- 1 2 Arya Dipa (18 January 2017). "Petition calls for disbandment of FPI". The Jakarta Post.

- ↑ "Biografi Ringkas Al Habib M. Rizieq bin Husein Syihab". Arrohim.com – Aneka Informasi Islami.

- ↑ "Habib Salim Asy-Syatiri Memuji Keberanian & Ketegasan Habib Rizieq Syihab". MudhiatulFata.

- 1 2 Budi Setiyarso; et al. (30 November 2010), "Street Warriors", Tempo magazine, English edition, p. 41

- ↑ "Pembekuan akun Twitter FPI 'bukan permintaan' Kominfo" (in Indonesian). BBC Indonesia. 16 January 2017.

- ↑ "Hard-liners ambush Monas rally". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta. 2 June 2008. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Arya Dipa (January 30, 2017). "Police declare FPI leader Rizieq Shihab suspect for alleged Pancasila defamation". The Jakarta Post.

- ↑ "Masalah GKI Yasmin Jadi Catatan Dunia".

- ↑ "Bekasi FPI Leader Murhali Implicated in Stabbing of HKBP Church Elder". Archived from the original on 2010-09-20.

- ↑ "Catatan Kronologis Penyegelan Gereja-gereja di Aceh Singkil".

- ↑ http://m.liputan6.com/news/read/2898273/demo-tolak-pembangunan-gereja-di-bekasi-ricuh-5-polisi-terluka

- ↑ Woodward, Mark; Rohmaniyah, Inayah; Amin, Ali; Ma’arif, Samsul; Coleman, Diana Murtaugh; Umar, Muhammad Sani (2012). "Ordering what is right, forbidding what is wrong:two faces of Hadhrami dakwah in contemporary Indonesia". 46 (2): 132 136 (our of pp. 105–46).

- ↑ "Indonesia: Ahmadiyya killings verdicts will not stem discrimination".

- ↑ "Indonesia's Ahmadis Look for a Home in Novel". Archived from the original on 2012-09-10.

- ↑ "'Deplorable' FPI Strikes Again". The Jakarta Globe. Jakarta. 25 June 2010. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Safrin La Batu (January 23, 2017). "FPI leader calls for withdrawal of banknotes with 'communist symbol'". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- ↑ Safrin La Batu (January 23, 2017). "FPI leader questioned for allegedly insulting rupiah". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- ↑ "Garut Police Take a Stance Against FPI". The Jakarta Globe. 30 May 2012.

- ↑ Bamualim, Chaider S. (2011). "Islamic Militancy and Resentment against Hadhramis in Post-Suharto Indonesia: A Case Study of Habib Rizieq Syihab and His Islam Defenders Front". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 31 (2): 267–281. doi:10.1215/1089201X-1264226.

- ↑ Jane Perlez (24 July 2006). "Playboy Indonesia: Modest Flesh Meets Muslim Faith". The New York Times. Denpasar. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Lady Gaga 'devastated' as Indonesia concert cancelled".

- ↑ "Irshad Manji book tour in Indonesia runs into trouble with Islamic 'thugs'".

- ↑ "KITAB UNDANG-UNDANG HUKUM PIDANA".

- ↑ "Police under fire for allowing sweeping FPI raids". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta. 31 December 2015.

- ↑ "Aksi Bela Islam". Wikipedia bahasa Indonesia, ensiklopedia bebas (in Indonesian). 2017-05-05.

- ↑ Iqbal T Lazuardi S (19 January 2017). "Protesters Deliver Petition, Demand FPI to be Disbanded". Tempo.co.

- ↑ Caroline Damanik (20 January 2017). "Demo, Ratusan Warga Dayak Minta FPI Dibubarkan". Kompas.com (in Indonesian).

- ↑ "University Students in Manado Take to Streets to Demand FPI Disbandment". Jakarta Globe.

- ↑ "FPI Involved in 34 Violence Cases in 2010-2011". February 19, 2012. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Senior FPI officials booted out of Palangkaraya". February 11, 2012. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Central Kalimantan officially rejects FPI". February 23, 2012.

External links

- (in Indonesian) Front Pembela Islam's Official Website

- (in Indonesian) FPI Online

- (in Indonesian) FPI & LPI's History

- (in Indonesian) Sunday, June 1, 2008 Monas provocation chronology

- (in Indonesian) Ruanghati