Navvab Safavi

| Navvab Safavi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Sayyid Mojtaba Mir-Lohi c. 1924 Tehran, Persia |

| Died |

January 18, 1956 (aged 31) Tehran, Iran |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Occupation | cleric • politician |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Shīʿah |

| Jurisprudence | Ja'fari |

| Political Party | Fada'iyan-e Islam |

| Alma mater | Najaf Seminary |

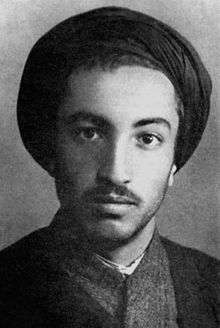

Sayyid Mojtaba Mir-Lohi (Persian: سيد مجتبی میرلوحی), more commonly known as Navvab Safavi (Persian: نواب صفوی), was an Iranian Shia cleric and founder of the Fada'iyan-e Islam group.

Early life

Born in Ghaniabad, Tehran into a well-known religious family in 1924,[1][2] he received his primary education in Tehran and left school after eighth grade when his father died.[3] His father, Seyyed Javad Mir-Lohi, was a cleric who was put in jail many years for having slapped Reza Shah's Minister of Justice, Ali Akbar Davar, in the face, and thus the young Navvab was raised by his maternal uncle, Seyyed Mahmood Navvab Safavi, whose name he eventually adopted.[4] It's said that "the family name was changed to Navvab Safavi (deputies of the Safavids) to identify with the famous Shi'ite dynasty of the Safavids, who in the sixteenth century made Shi'ism the state religion of Iran."[3] Growing up during this period of militant secularization, after briefly (for few months) working in Abadan's petroleum installations in Khuzestan province, for the British-owned Iranian Oil Company, he decided, in 1943, to pursue religious studies at Najaf.[5] He is said to have been known for his striking looks and his "mesmerizing" speaking ability,[6] and compared his own charisma and magnetism over the masses to that of Hassan-i Sabbah, the leader of the Assassins.[7]

Career

Safavi founded the Fada'iyan-e Islam organization in 1945,[3] and began recruiting like-minded individuals. Like the Muslim Brotherhood, a group he was in deep connection with and even met Sayyid Qutb later in 1953,[8] Navvab Safavi believed that Islamic society needed to be purified. To do this he organized carefully planned assassinations to rid Islam of "corrupting individuals," often prime ministers of Iran's government.

Amir Taheri claims that Safavi was "the man who introduced Ayatollah Khomeini to the Muslim Brotherhood and their ideas," who "spent long hours together" with Khomeini in discussion, and visited him in Qom on a number of occasions during 1943 and 1944.[9] However, this is contradicted by the fact that the Muslim Brotherhood is a fundamentalist Sunni organisation that is against Shi'a Islam and considers it to be a heresy.[10] The refutation of Taheri above is incorrect as Muslim Brotherhood was set up to unify Moslems (or the birth of radical Islam) and overcome divisions within Islam. Refer to history of the brotherhood and the influence of such figures as Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī.

He and his organization were responsible for the assassinations, or attempted assassinations of politicians Abdolhossein Hazhir, Hossein Ala' (he survived the attempt), Prime Minister Haj Ali Razmara,[11] and historian Ahmad Kasravi,[11]

Safavi and his group were closely associated with Abol-Ghasem Kashani and supported but were not members of Mohammad Mosaddegh's National Front. Safavi worked with Kashani, helping organize bazaar strikes against Premier Ahmad Qavam, public meetings in support of Palestinian Arabs, and a violent demonstration in 1948 against Premier Abdolhossein Hazhir.[12] When the Shah appointed National Front leader Mohammed Mossadegh to the post of prime minister, Safavi expected his objectives would be furthered. He demanded the government drive the British out, and that it release "with honour and respect" the assassin of Razmara. When that didn't happen, Safavi announced "we have broken away irrevocably from Kashani's National Front. They promised to set up an Islamic country according to the precepts of the Koran. Instead they have imprisoned our brothers." He later warned, "there are others who must be pushed down the incline to hell", words which would pass on to Mossadegh and further alienate him.[13]

Thus relations between Kashani and Safavi, not to mention Mosaddegh, became "strained." On May 10, 1951, Navvab Safavi declared, "I invite Mosaddegh, other members of the National Front and Ayatollah Kashani, to an ethical trial.'[14]

Arrest and execution

Prime Minister Mosaddegh, who was preoccupied with the nationalization of the oil industry, found these activities "disruptive." On 8 June 1951 he ordered the arrest of Safavi, who stayed there until his release in February 1953. Six months later Mosaddegh was overthrown in a coup d'état. Like Kashani, Safavi supported the coup against Mosaddegh and "in the years immediately following the coup Navvab Safavi enjoyed a close association with the court and the government of Prime Minister General Fazlollah Zahedi." By 1955 it became clear the regime would not be instituting strict enforcement of Shariah law and Islamization of Iran, and was instead becoming more pro-Western. On 22 November, after an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Hosein Ala', Navvab Safavi and some of his followers were arrested. Following a summary trial Safavi and three other members of Fada'iyan-e Islam were executed on 25 December. The clerical establishment did not attempt to intervene on their behalf.[14]

Ideology

The main work detailing his vision of the world is Barnameh-ye Enqelabi-ye Fada'ian-e Eslam (The Revolutionary Programme of Fada'ian-e Eslam), "published in October/November 1950, in the heat of the debates over the nationalization of the oil industry", where he exposes a paradigm close to that of the utopian socialists like Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier or Robert Owen.[15]

In philosophy and moral psychology, he proposed that "the human mind is the arena of a continual confrontation between the desires of the soul (nafs) and the restraining force of reason ('aql)", and the latter should refrain the carnal desires of the former, like fornication or drinking alcohol.[16]

In education, he favoured "compulsory elementary education for five years, and high school would train students in the areas of students' specialization. Only courses such as chemistry, physics, natural sciences, mathematics, and medicine, which are useful for society, would be taught" so "in this way those students who do not make it to college would have learned a trade when they complete high school", while he also promoted single-sex education, all of which would influence the educational policies of Ayatollah Khomeini.[17]

In economy, he proposed a Third Position, refuting both western capitalism and communism for an Islamic vision, which is similar to Ayatollah Khomeini's anti-Soviet and anti-US position. His ideology has been characterized as "a Sismondian capitalism of shopkeepers and artisans where altruism, charity, and religious taxes (zakat and khoms) act as levelling devices in a society that would honour everyone equally and would provide for all their needs", "the shopkeepers and artisans would be living in a world of total harmony with the wealthy and fortunate merchants, while the corrupt and arrogant capitalist thieves and embezzlers of public funds would be done away with", whereas the government "would carry on certain responsibilities. It would maintain law and order and would make sure that Islamic codes of conduct are strictly enforced. It would educate the youth (public education by government is accepted) and carry out other social responsibilities."[18]

In geopolitics, like many Iranian nationalists of his time, he's particularly critical of Great Britain and the Soviet Union, yet another feature Ayatollah Khomeini made his own.[19] He was also strongly anti-Zionist, proclaiming that "the pure blood of the brave devotees of Islam is boiling to help the Moslem Palestinian brothers."[20] In fact, apart from the obvious pan-Islamic tones of the movement, he was also somehow a nationalist in the sense that "the Fada'iyan's ideology combined religious zeal and belief in the supremacy of Shi'ite Islam with elements of Iranian nationalism. The Fada'iyan sought to 'purify the Persian language' and hoped to bring the Iranian-Shi'ite lands together and establish an Islamic government."[21]

The main difference with the later founder of the Islamic Republic, though, and a radical one, is that he never advocated for a theocracy, as he accepts the monarchy, where "the Shah is viewed as the father of the family. He should be benevolent and fatherly in ruling the people. His faith and virtues should be such that people learn from him religious faith and virtues. He, as a father, should know how everyone is doing and that no one will go hungry or lack clothing. Then, 'as long as there is anyone alive in the family no one would dare to be disrespectful toward him, not to mention wanting to expel him from his home and family. Yes! The Shah must be a father, to be a father and the Shah.'".[22]

Apart from Ayatollah Khomeini, Navvab's vision would influence many other important players of the Islamic Republic, for instance the scholar Morteza Motahhari,[23] or being, with Jalal Al-e Ahmad and Ahmad Fardid, one of the main ideological pillars of the former conservative president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[24] The current Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, goes as far as saying "I have no doubt that it was Navab Safavi who first kindled the fire of revolutionary Islam in my heart."[25]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mojtaba Mir-Lowhi. |

- ↑ Saeed Rahnema, Sohrab Behdad, Iran After the Revolution: Crisis of an Islamic State, I.B.Tauris (1996), p. 79

- ↑ Vanessa Martin, Creating an Islamic State: Khomeini and the Making of a New Iran, I.B.Tauris (2003), p. 129

- 1 2 3 Farhad Kazemi, "The Fada'iyan-e Islam: Fanaticism, Politics and Terror" in Said Amir Arjomand (ed.), From Nationalism to Revolutionary Islam, SUNY Press (1984), p. 160

- ↑ Sohrab Behdad (1997), "Islamic Utopia in pre‐revolutionary Iran: Navvab Safavi and the Fada'ian‐e Eslam", Middle Eastern Studies, 33:1, 40-41

- ↑ Ali Rahnema, Behind the 1953 Coup in Iran: Thugs, Turncoats, Soldiers, and Spooks, Cambridge University Press (2014), p. 307

- ↑ Taheri, Amir (1986). The Spirit of Allah: Khomeini and the Islamic revolution. Adler & Adler. ISBN 978-0-917561-04-7. , p. 98

- ↑ Farhad Kazemi, "The Fada'iyan-e Islam: Fanaticism, Politics and Terror" in Said Amir Arjomand (ed.), From Nationalism to Revolutionary Islam, SUNY Press (1984), p. 169

- ↑ Syed Viqar Salahuddin, Islam, peace, and conflict: based on six events in the year 1979, which were harbingers of the present day conflicts in the Muslim world, Pentagon Press (2008), p. 5

- ↑ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 98, 102.

- ↑ Egypt’s Shiite Minority: Between the Egyptian Hammer and the Iranian Anvil from the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs

- 1 2 Ostovar, Afshon P. (2009). "Guardians of the Islamic Revolution Ideology, Politics, and the Development of Military Power in Iran (1979–2009)" (PhD Thesis). University of Michigan. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ Ervand Abrahamian, Iran between Two Revolutions (Princeton University Press, 1982), pp. 258-9.

- ↑ The Reader's Digest, Volume 59, p. 203

- 1 2 Islamic Utopia in Pre-Revolutionary Iran: Navvab Safavi and the Fada'ian-e Eslam, Sohrab Behdad Middle Eastern Studies, January 1997

- ↑ Sohrab Behdad (1997), "Islamic Utopia in pre‐revolutionary Iran: Navvab Safavi and the Fada'ian‐e Eslam", Middle Eastern Studies, 33:1, 52

- ↑ Sohrab Behdad (1997), "Islamic Utopia in pre‐revolutionary Iran: Navvab Safavi and the Fada'ian‐e Eslam", Middle Eastern Studies, 33:1, 54

- ↑ Sohrab Behdad, "Utopia of Assassins: Nawab Safavi and the Fada'ian-e Eslam in Pre-revolutionary Iran" in Ramin Jahanbegloo, Iran: Between Tradition and Modernity, Lexington Books (2004), p. 83

- ↑ Sohrab Behdad, "Utopia of Assassins: Nawab Safavi and the Fada'ian-e Eslam in Pre-revolutionary Iran" in Ramin Jahanbegloo, Iran: Between Tradition and Modernity, Lexington Books (2004), pp. 83-86

- ↑ Sohrab Behdad (1997), "Islamic Utopia in pre‐revolutionary Iran: Navvab Safavi and the Fada'ian‐e Eslam", Middle Eastern Studies, 33:1, 53

- ↑ Farhad Kazemi, "The Fada'iyan-e Islam: Fanaticism, Politics and Terror" in Said Amir Arjomand (ed.), From Nationalism to Revolutionary Islam, SUNY Press (1984), p. 162

- ↑ Farhad Kazemi, "The Fada'iyan-e Islam: Fanaticism, Politics and Terror" in Said Amir Arjomand (ed.), From Nationalism to Revolutionary Islam, SUNY Press (1984), p. 170

- ↑ Sohrab Behdad (1997), "Islamic Utopia in pre‐revolutionary Iran: Navvab Safavi and the Fada'ian‐e Eslam", Middle Eastern Studies, 33:1, 55

- ↑ S. Khalil Toussi, "Introduction" in Murtada Mutahhari, Sexual Ethics in Islam and in the Western World, ICAS Press (2011), p. vii

- ↑ Avideh Mayville, "The Religious Ideology of Reform in Iran" in J. Harold Ellens (ed.), Winning Revolutions: The Psychosocial Dynamics of Revolts for Freedom, Fairness, and Rights [3 volumes], ABC-CLIO (2013), p. 311

- ↑ Yvette Hovsepian-Bearce, The Political Ideology of Ayatollah Khamenei: Out of the Mouth of the Supreme Leader of Iran, Routledge (2015), p. 30

- 'Alí Rizā Awsatí (عليرضا اوسطى), Iran in the Past Three Centuries (Irān dar Se Qarn-e Goz̲ashteh - ايران در سه قرن گذشته), Volumes 1 and 2 (Paktāb Publishing - انتشارات پاکتاب, Tehran, Iran, 2003). ISBN 964-93406-6-1 (Vol. 1), ISBN 964-93406-5-3 (Vol. 2).

- Mazandi, Yousof (United Press Iranian correspondent) and Edwin Muller, Government by Assassination, Reader's Digest, September 1951.

- Taheri, Amir. The Spirit of Allah Khomeini and the Islamic revolution, Bethesda, Maryland : Adler & Adler, c1985

External links

- Greatscholars News (About Navab Safvi)