Fourth Council of the Lateran

| Fourth Council of the Lateran (Council of Lateran IV) | |

|---|---|

| Date | 1215 |

| Accepted by | Roman Catholicism |

Previous council | Third Council of the Lateran |

Next council | First Council of Lyon |

| Convoked by | Pope Innocent III |

| President | Pope Innocent III |

| Attendance | 71 patriarchs and metropolitans, 412 bishops, 900 abbots and priors |

| Topics | Crusader States, Investiture Controversy, Filioque |

Documents and statements | seventy papal decrees, transubstantiation, papal primacy, conduct of clergy, confession and communion at least once a year, Fifth Crusade |

| Chronological list of ecumenical councils | |

| Part of a series on |

| Ecumenical councils of the Catholic Church |

|---|

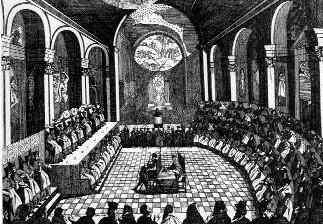

Renaissance depiction of the Council of Trent |

| Antiquity (c. 50 – 451) |

| Early Middle Ages (553–870) |

| High and Late Middle Ages (1122–1517) |

| Modernity (1545–1965) |

|

|

The Fourth Council of the Lateran was convoked by Pope Innocent III with the papal bull Vineam domini Sabaoth of 19 April 1213, and the Council gathered at Rome's Lateran Palace beginning 11 November 1215.[1] Due to the great length of time between the Council's convocation and meeting, many bishops had the opportunity to attend. It is considered by the Catholic Church to have been the twelfth ecumenical council and is sometimes called the "Great Council" or "General Council of Lateran" due to the presence of seventy-one patriarchs and metropolitan bishops, four hundred and twelve bishops, and nine hundred abbots and priors together with representatives of several monarchs.[1]

During this council, the teaching on transubstantiation— a doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church which describes the method by which the bread and wine offered in the sacrament of the Eucharist becomes the actual blood and body of Christ— was defined.

Background

Lateran IV stands as the high-water mark of the medieval papacy. Its political and ecclesiastical decisions endured down to the Council of Trent while modern historiography has deemed it the most significant papal assembly of the Later Middle Ages.[2] The Fourth Lateran Council was the largest and most representative of the medieval councils to that date.[3]

In summoning the bishops to a general council, Innocent III emphasized that reforms must be made in the Church and that a new crusade to the Holy Land must be launched. He also reminded them that it was not appropriate that their retinue include birds and hunting dogs.[4]

The agenda laid out in Vineam domini Sabaoth included reform of the Church, the stamping out of heresy, establishing peace and liberty, and calling for a new crusade.[4] During this council, the doctrine of transubstantiation— a Church doctrine which describes the method by which the bread and wine offered in the sacrament of the Eucharist becomes the actual blood and body of Christ— was infallibly defined.[5] The scholarly consensus is that the constitutions were drafted by Innocent III himself.[3]

In secular matters, the Council confirmed the elevation of Frederick II as Holy Roman Emperor.[3]

There were violent scenes between the partisans of Simon de Montfort among the French bishops and those of the Count of Toulouse. Raymond VI of Toulouse, his son (afterwards Raymond VII), and Raymond-Roger of Foix attended the Council to dispute the threatened confiscation of their territories; Bishop Foulques and Guy de Montfort (brother of Simon) argued in favour of the confiscation. All of Raymond VI's lands were confiscated, save Provence, which was kept in trust to be restored to his son, Raymond VII.[6] Pierre-Bermond of Sauve's claim to Toulouse was rejected, and Toulouse was awarded to de Montfort;[6] the lordship of Melgueil was separated from Toulouse and entrusted to the bishops of Maguelonne.

Canons

Canons presented to the Council included:[1]

Faith and heresy

- Canon 1: The Creed Caput Firmiter[7]—Exposition of the Catholic Faith and of the sacraments. It includes a brief reference to transubstantiation.[8]

- Canon 2: Condemnation of the doctrines of Joachim of Fiore and of Amalric of Bena.

- Canon 3: Procedure and penalties against heretics and their protectors. If those suspected of heresy should neglect to prove themselves innocent, they are excommunicated. If they continue in the excommunication for twelve months they are to be condemned as heretics. Princes are to be admonished to swear that they will banish all whom the Church points out as heretics. This canon mandates that those pointed by the Church as heretics shall be expelled by the secular authorities or they will be excommunicated if failing to do so.

- Canon 4: Exhortation to the Greeks to reunite with the Roman Church.[8]

Order and discipline

- Canon 5: Proclamation of the papal primacy recognized by all antiquity. After the pope, primacy is attributed to the patriarchs in the following order: Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem.

- Canon 6: Provincial councils must be held annually for the reform of morals, especially those of the clergy. This was to ensure that the canons adopted would be implemented.

- Canon 7: Set down the responsibility of the bishops for the reform of their subjects.

- Canon 8: Procedure in regard to accusations against ecclesiastics. Until the French Revolution, this canon was of considerable importance in criminal law, not only ecclesiastical but even civil.

- Canon 9: Celebration of public worship in places where the inhabitants belong to nations following different rites.

Ecclesiastical discipline

- Canon 10: Ordered the appointment of preachers and penitentiaries to assist in the discharge of the episcopal functions of preaching and penance

- Canon 11: The decree of 1179, about a school in each cathedral having been entirely ignored, was re-enacted, and a lectureship in theology ordered to be founded in every cathedral.

- Canon 12: Abbots and priors are to hold their general chapter every three years.

- Canon 13: A good deal of Innocent III's time had been spent judging complaints of bishops against the religious orders. This canon forbade the establishment of new religious orders. Those who wished to found a new house were to choose an existing approved rule. It is this canon that led Saint Dominic to adopt the Rule of St. Augustine.[8]

Clerical morality

- Canons 14–17: Against the irregularities of the clergy — e.g., incontinence (wantonness), drunkenness, attendance at farces and histrionic exhibitions.

- Canon 18: Clerics may neither pronounce nor execute a sentence of death. Nor may they act as judges in extreme criminal cases, or take part in matters connected with judicial tests and ordeals. This last prohibition, since it removed the one thing that gave the ordeal its value, was the beginning of the end of Trial by ordeal.[4]

Religious cult

- Canon 19: Household goods must not be stored in churches unless there be an urgent necessity. Churches, church vessels, and the like must be kept clean.

- Canon 21, the famous "Omnis utriusque sexus", which commands every Christian who has reached the years of discretion to confess all his, or her, sins at least once a year to his, or her, own[9] priest. This canon did no more than confirm earlier legislation and custom, although it is sometimes incorrectly quoted as commanding the use of sacramental confession for the first time. In actuality the confession came into existence over a long period of time.[10] However, this was the first time that it took the shape of the Christian confessional as we know it today.[10]

- Canon 22: Before prescribing for the sick, physicians shall be bound under pain of exclusion from the Church, to exhort their patients to call in a priest, and thus provide for their spiritual welfare.

Appointments and elections

- Canons 23–30 regulate ecclesiastical elections and the collation (assignment) of benefices.

- Canon 26: Ecclesiastical procedure.

Legal procedure

- Canon 35: Defendants must not appeal without good cause before sentence is given; if they do, they are to be charged expenses.

- Canon 36: Judges may revoke comminatory and interlocutory sentences and proceed with the case.

Relations with the secular power

- Canon 43: Clerics should not take oaths of fealty to laymen without lawful cause.

- Canon 44: Lay princes should not usurp the rights of churches.

Excommunication

- Canon 47: Excommunication may be imposed only after warning in the presence of suitable witnesses and for manifest and reasonable cause.

- Canon 49: Excommunications to be neither imposed nor lifted for payment.

Marriage

Tithes

- Canon 53: The council condemned those who had their property cultivated by others (non-Christians) in order to avoid tithes.

- Canon 54: Tithe payments have priority over all other taxes and dues.

Religious Orders

- Canon 57: Gave precise instructions on the interpretation of the privilege of celebrating religious services during interdict, enjoyed by some orders.

Simony

- Canon 63: No fees are to be exacted for the consecration of bishops, the blessing of abbots or the ordination of clerics.

- Canon 64: Monks and nuns may not require payment for entry into the religious life.

Regulations relating to Jews and Muslims

- Canon 67: Jews may not charge extortionate interest.

- Canons 68: Jews and Muslims shall wear a special dress to enable them to be distinguished from Christians so that no Christian shall come to marry them ignorant of who they are.[12]

- Canon 69: Declares Jews disqualified from holding public offices, incorporating into ecclesiastical law a decree of the Holy Christian Empire.[12]

- Canon 70: Takes measures to prevent converted Jews from returning to their former belief.[12]

In addition, it threatened excommunication to those who supplied ships, arms, and other war materials to the Saracens.

Effective application of the decrees varied according to local conditions and customs.[3]

References

- 1 2 3

- ↑ Concilium Lateranense IV

- 1 2 3 4 Duggan, Anne. "Conciliar Law 1123-1215: The Legislation of the Four Lateran Councils", The History of Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140–1234: From Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX, (Wilfried Hartmann and Kenneth Pennington, eds.) (History of Medieval Canon Law; Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2008) 318–366

- 1 2 3 Pennington, Kenneth. "The Fourth Lateran Council, its Legislation, and the Development of Legal Procedure", CUA

- ↑ Walker, Greg (1993-05-01). "Heretical Sects in Pre-Reformation England". History Today. Retrieved 2017-05-30. – via HighBeam (subscription required)

- 1 2 The Albigensian Crusade and heresy, Bernard Hamilton,The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, C.1198-c.1300, ed. Rosamond McKitterick, David Abulafia, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 169.

- ↑ Beginning Firmiter credimus et simpliciter confitemur, text in Henricius Denzinger and Iohannes Bapt. Umberg, SJ (1937), Enchiridion Symbolorum, Definitionum et Declarationum de Rebus Fidei et Morum, Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, Canon 1, # 428–430, pp. 199–200.

- 1 2 3 Jarvis, Matthew OP. "Councils of Faith". Order of Preachers.

- ↑ At that time this referred at least chiefly to the parish priest. However, its actual meaning is what is now called a "priest with faculties", specifically the authority to hear the respective penitent's confession. This authority is now more broadly distributed among priests.

- 1 2 Abercrombie, N., Hill, S., & Turner, B. S. (1986). Sovereign individuals of capitalism. London: Allen & Unwin.

- ↑ Fourth Lateran Council, Canon 50

- 1 2 3 Gottheil, Richard and Vogelstein, Hermann. "Church councils", Jewish Encyclopedia

External links

- Canons of the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215

- Fourth Lateran Council

- Un document retrouvé by Achille Luchaire, in Journal des savants, n.s. 3 (1905), 557–567, including a list of participants in the Council

- Woods, Marjorie Curry and Rita Copeland. "Classroom and Confession". The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature, pp. 376–406. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-521-89046-5.