Islamization of Egypt

The Islamization of Egypt occurred as a result of the Muslim conquest by the Arabs led by Amr ibn al-Aas, the military governor of Palestine. The indigenous Coptic population of Egypt underwent a large scale gradual conversion from Coptic Christianity to Islam. This process of Islamization was accompanied by a simultaneous wave of Arabization. These factors resulted in Muslims becoming a majority in Egypt between 10th and 14th century, and the Egyptian acculturating into Arab identity and replacing their native Coptic and Greek languages with Arabic as their sole vernacular.[1]

Islamic links to Coptic Egypt predates its conquest by the Arabs. According to Muslim tradition, Mohammed married a Copt; Maria al-Qibtiyya. In 641 AD, Egypt was invaded by the Arabs who faced off with the Byzantine army. Local resistance by the Egyptians began to materialize shortly thereafter and would last until at least the ninth century.[2][3]

The Arabs imposed a special tax, known as jizya, on the Christians who acquired the protected status of dhimmis, the taxation was justified on protection grounds since local Christians were never drafted to serve in an army. Arab conquerors generally preferred not to cohabit with native Copts in their towns and established new colonies, like Cairo. Heavy taxation at times of state hardships was a reason behind Coptic Christians organizing resistance against the new rulers. This resistance mounted to armed rebellions against the Arabs in a number of instances, such as during the Bashmurian revolt in the Delta, which were sometimes successful.

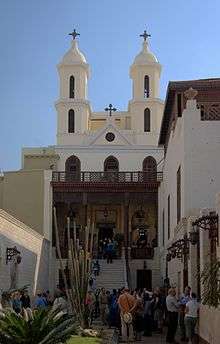

The Arabs in the 7th century seldom used the term Egyptian, and used instead the term qbt, which was adopted into English as Copt, to describe the people of Egypt. Thus, Egyptians became known as Copts, and the non-Chalcedonian Egyptian Church became known as the Coptic Church. The Chalcedonian Church remained known as the Melkite Church. In their own native language, Egyptians referred to themselves as ⲛⲓⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ (/ni-rem-en-kēmi/ "the people of Egypt"). Religious life remained largely undisturbed following the Arab occupation, as evidence by the rich output of Coptic arts in monastic centers in Old Cairo (Fustat) and throughout Egypt. Conditions, however, worsened shortly after that, and in the eighth and ninth centuries, during the period of the great national resistance against the Arabs, Muslim rulers banned the use of human forms in art (taking advantage of an iconoclastic conflict in Byzantium) and consequently destroyed many Coptic paintings and frescoes in churches.[4]

The Fatimid period of Islamic rule in Egypt was tolerant with the exception of the violent persecutions of caliph Al-Hakim. The Fatimid rulers employed Copts in the government and participated in Coptic and local Egyptian feasts. Major renovation and reconstruction of churches and monasteries were also undertaken. Coptic arts flourished, reaching new heights in Middle and Upper Egypt.[5] Persecution of Egyptian Christians, however, reached a peak in the early Mamluk period following the Crusader wars. Many forced conversions of Christians were reported. Monasteries were occasionally raided and destroyed by marauding Bedouin, but at least in some case were later rebuilt and reopened by Copts.

See also

References

- ↑ Clive Holes, Modern Arabic: structures, functions, and varieties, Georgetown University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-1-58901-022-2, M1 Google Print, p. 29.

- ↑ Mawaiz wa al-'i'tibar bi dhikr al-khitat wa al-'athar (2 vols., Bulaq, 1854), by Al-Maqrizi

- ↑ Chronicles, by John of Nikiû

- ↑ Kamil, p. 41

- ↑ Kamil, op cit.

Sources

- Betts, Robert B. (1978). Christians in the Arab East: A Political Study (2nd rev. ed.). Athens: Lycabettus Press.

- Charles, Robert H. (2007) [1916]. The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu: Translated from Zotenberg's Ethiopic Text. Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing.

- Kamil, Jill. Coptic Egypt: History and a Guide. Revised Ed. American University in Cairo Press, 1990.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450-680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.