Harar

| Harar ሓረር (in Amharic) هرر(in Arabic) | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

Old Harar enclosed by the jugol (defensive wall) | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): City of Saints | ||

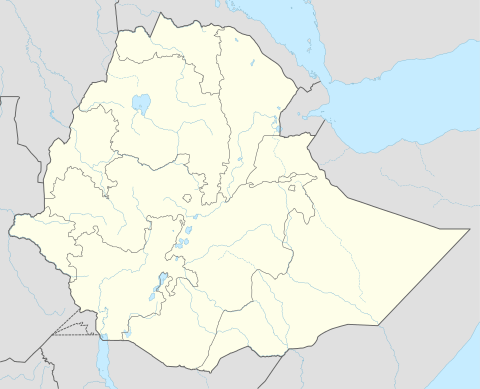

Harar Location within Ethiopia | ||

| Coordinates: 9°19′N 42°7′E / 9.317°N 42.117°E | ||

| Country | Ethiopia | |

| Region | Harari | |

| Zone | East Hararghe Zone | |

| Government | ||

| • President | Murad Abdulhadi | |

| Elevation | 1,885 m (6,184 ft) | |

| Population (2012) | ||

| • Total | 151,977 | |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) | |

| UNESCO World Heritage site | ||

| Official name | Harar Jugol, the Fortified Historic Town | |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, iv, v | |

| Reference | 1189 | |

| Inscription | 2006 (30th Session) | |

| Area | 48 ha | |

Harar (Harari: ሐረር),[lower-alpha 1] and known to its inhabitants as Gēy (Harari: ጌይ),[2] is a walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It was formerly the capital of Hararghe and now the capital of the modern Harari Region of Ethiopia. The city is located on a hilltop in the eastern extension of the Ethiopian Highlands, about five hundred kilometers from the national capital Addis Ababa at an elevation of 1,885 meters. Based on figures from the Central Statistical Agency in 2005, Harar had an estimated total population of 122,000, of whom 60,000 were males and 62,000 were females.[3] According to the census of 1994, on which this estimate is based, the city had a population of 76,378.

For centuries, Harar has been a major commercial center, linked by the trade routes with the rest of Ethiopia, the entire Horn of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and, through its ports, the outside world. Harar Jugol, the old walled city, was listed as a World Heritage Site in 2006 by UNESCO in recognition of its cultural heritage.[4] It is sometimes known in Arabic as مدينة الأَوْلِيَاء "the City of Saints". According to UNESCO, it is "considered 'the fourth holy city' of Islam" with 110 mosques, three of which date from the 10th century and 102 shrines.[5][6]

The Fath Madinat Harar records that the cleric Abadir Umar ar-Rida and several other religious leaders settled in Harar circa 1216 (612 hijri years).[7] Harar was later made the new capital of the Adal Sultanate in 1520 by the Somali Sultan Abu Bakr ibn Muhammad.[8] The city saw a political decline during the ensuing Emirate of Harar, only regaining some significance in the Khedivate of Egypt period. During the Ethiopian Empire, the city decayed while maintaining a certain cultural prestige. Today, it is the seat of the Harari Region.

History

It is likely the original inhabitants of the region were the Harla people.[9] In its early history, the city was under an alliance called the Zeila confederate states.[10] According to twelfth century Jewish traveler Benjamin Tudela, Zeila region was the land of the Havilah, confined by Al-Habash in the west.[11][12] In the ninth century, Harar was under the Makhzumi dynasty.[13][14] Harar Called Gēy ("the City") by its inhabitants Harari people, Harar emerged as the center of Islamic culture and religion in the Horn of Africa during end of the Middle Ages.

According to the Fath Madinat Harar, an unpublished history of the city in the 13th century, the cleric Abadir Umar ar-Rida, along with several other religious leaders, came from the Arabian Peninsula to settle in Harar circa 612H (1216 CE). Abadir was met by the Harla (Harari people) , Gaturi and Argobba.[15] Abadir's brother Fakr ad-Din subsequently founded the Sultanate of Mogadishu.[16]

According to the 14th century chronicles of Amda Seyon I, Gēt (Gēy) was an Arab colony in Harla country.[17] During the Middle Ages, Harar was part of the Adal Sultanate, becoming its capital in 1520 under Sultan Abu Bakr ibn Muhammad. The sixteenth century was the city's Golden Age. The local culture flourished, and many poets lived and wrote there. It also became known for coffee, weaving, basketry and bookbinding.

From Harar, Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, also known as "Gurey" and "Grañ" (both meaning "the Left-handed"), launched a war of conquest in the sixteenth century that extended the polity's territory and threatened the existence of the neighboring Christian Ethiopian Empire. His successor, Emir Nur ibn Mujahid, built a protective wall around the city.[18] Four meters in height with five gates, this structure, called Jugol, is still intact and is a symbol of the town to the inhabitants. Silt'e, Wolane, Halaba and Harari, lived in Harar while the former three moved to the Gurage region.[19]

The Emirate of Harar also struck its own currency, the earliest possible issues bearing a date that may be read as AH 615 (= AD 1218/19); but definitely by AD 1789 the first coins were issued, and more were issued into the nineteenth century.[20]

_LCCN2014683643.jpg)

Following the death of Emir Nur, Harar began a steady decline in wealth and power. A later ruler, Imam Muhammed Jasa, a kinsman of Ahmad Gragn, yielded to the pressures of increasing Oromo raids and in 1577 abandoned the city, relocating to Aussa and making his brother ruler of Harar. The new base not only failed to provide more security from the Oromos, it attracted the hostile attention of the neighboring Afars who raided caravans traveling between Harar and the coast. The Imams of Aussa declined over the next century while Harar regained its independence under `Ali ibn Da`ud, the founder of a dynasty that ruled the city from 1647 until 1875, when it was conquered by Egypt.[21]

During the period of Egyptian rule (1875-1884), Arthur Rimbaud lived in the city as the local functionary of several different commercial companies based in Aden; he returned in 1888 to resume trading in coffee, musk, and skins until a fatal disease forced him to return to France. A house said to have been his residence is now a museum.[22]

In 1885, Harar regained its independence, but this lasted only two years until 6 January 1887 when the Battle of Chelenqo led to Harar's incorporation into the Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia's growing Empire based in Shewa.

Harar lost some of its commercial importance with the creation of the Addis Ababa - Djibouti Railway, initially intended to run via the city but diverted north of the mountains between Harar and the Awash River to save money. As a result of this, Dire Dawa was founded in 1902 as New Harar.

.jpg)

Harar was captured by Italian troops under Marshall Rodolfo Graziani during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War on 8 May 1937. The 1st battalion of the Nigeria Regiment, advancing from Jijiga by way of the Marda Pass, captured the city for the allies 29 March 1941.[23] Following the conclusion of the Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement in 1944, the government of the United Kingdom were granted permission to establish a consulate in Harar, although the British refused to reciprocate by allowing an Ethiopian one at Hargeisa. After numerous reports of British activities in the Haud that violated the London Agreement of 1954, the Ethiopian Ministry of Foreign Affairs ordered the consulate closed March 1960.[24]

In 1995, the city and its environs became an Ethiopian region (or kilil) in its own right. A pipeline to carry water to the city from Dire Dawa is currently under construction.

According to Sir Richard Burton Harar is the birthplace of the khat plant.[25] The original domesticated coffee plant is also said to have been from Harar.[26]

Climate

The climate of Harar is classified as subtropical highland climate (Cwb) in Köppen-Geiger climate classification system.

Throughout the year, afternoon temperatures are warm to very warm, whilst mornings are cool to mild. Rain falls between March and October with a peak in August, whilst November to February is usually dry.

| Climate data for Harar | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.3 (77.5) |

26.3 (79.3) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.9 (75) |

26.1 (79) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.9 (53.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.3 (56) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 17 (0.67) |

20 (0.79) |

57 (2.24) |

84 (3.31) |

91 (3.58) |

68 (2.68) |

99 (3.9) |

126 (4.96) |

94 (3.7) |

49 (1.93) |

12 (0.47) |

6 (0.24) |

723 (28.47) |

| Source: Climate-Data[27] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

During his visit in the 19th century era of Egyptian occupation, Paultischke describes the town as having roughly 40,000 inhabitants with 25,000 of these being Hararis, 6,000 Oromo, 5,000 Somalis, 3,000 other Ethiopians as well as a minority of Europeans and Asians.[28]

_(14586268478).jpg)

The inhabitants of Harar today represent several different Afroasiatic-speaking ethnic groups, both Muslim and Christian, including the Oromo people, Somalis, Amhara people, Gurage people and Tigrayans. The Harari people, who refer to themselves as Gēy 'Usu ("People of the City") are a Semitic-speaking people. Their language, Harari, constitutes an Ethiopian Semitic pocket in a predominantly Cushitic-speaking region. Due to ethnic cleansing campaign committed against Hararis by the Haile Selassie regime, Hararis comprise less than 10% of the population of their city today.[29]

The Somali tribes surrounding Harar are mainly from the Dir clans of the Madaxweyne Dir-Akisho, Gadabuursi and Issa. They represent the most native Somali clans in the region.[30][31][32]

Attractions

.jpg)

Besides the stone wall surrounding the city, the old town is home to 110 mosques and many more shrines, centered on Feres Magala square. Notable buildings include Medhane Alem Cathedral, the house of Ras Mekonnen, the house of Arthur Rimbaud, the sixteenth century Jami Mosque and historic Great Five Gates of Harar. Harrar Bira Stadium is the home stadium for the Harrar Beer Bottling FC. One can also visit the market.

A long-standing tradition of feeding meat to spotted hyenas also evolved during the 1960s into an impressive night show for tourists.[33] (See spotted hyenas in Harar.)

Other places of interest include the highest amba overlooking the city, the Kondudo or "W" mountain, which hosts an ancient population of feral horses. A 2008 scientific mission has unleashed efforts for their conservation, as the animals are greatly endangered.[34]

The Harar Brewery was established in 1984. Its beers can be sampled at the brewery social club adjacent to the brewery in Harar.[35][36]

Intercity bus service is provided by the Selam Bus Line Share Company.

Sister cities

- Template:Arta (Djibouti) Arta, Djibouti

Notable residents

- 'Abd Allah II ibn 'Ali 'Abd ash-Shakur, last emir of Harar

- Abadir Umar ar-Rida, Muslim cleric

- Amha Selassie, Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire (Designate)

- Mahfuz, Imam and General of the Adal Sultanate

- Bati del Wambara, wife of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi

- Nur ibn Mujahid, Emir of Harar

- Abdullah al-Harari, leader of al-Ahbash

- Malik Ambar, Leader of Ahmadnagar Sultanate

- `Ali ibn Da`ud, Founder of Emirate of Harar

- Haboba, First Emir of Harar

- Arthur Rimbaud, the French poet, settled as a merchant in Harar between 1880 and 1891

See also

- Harar Brewery

- Coffee production in Ethiopia#Harar

- Harari language

- Harari people

- Hargeisa, a city in Somalia also called "Little Harar"

- Islam in Ethiopia

- Project Harar

- Silt'e people, an ethnic claiming to originate from Harar

- World Heritage Sites in Ethiopia, List of

Notes

- ↑

- ↑ Leslau 1959, p. 276.

- ↑ CSA 2005 National Statistics, Table B.4

- ↑ "Panda sanctuary, tequila area join UN World Heritage sites". Un.org. 2006-07-13. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ↑ "Harar Jugol, the Fortified Historic Town". World Heritage List. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

It is considered 'the fourth holy city' of Islam, having been founded by a holy missionary from the Arabic Peninsula.

- ↑ "Five new heritage sites in Africa". BBC. July 13, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

Harar Jugol, seen as the fourth holiest city of Islam, includes 82 mosques, three of which date from the 10th Century, and 102 shrines.

- ↑ Siegbert Uhlig, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: He-N, Volume 3, (Otto Harrassowitz Verlag: 2007), pp.111 & 319.

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst, History of Ethiopian Towns (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1982), p. 49.

- ↑ Gebissa, Ezekiel (2004). Leaf of Allah: Khat & Agricultural Transformation in Harerge, Ethiopia 1875-1991. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-85255-480-7. , page 36

- ↑ Wehib, Ahmed (October 2015). History of Harar and Harari (PDF). Harari people regional state, culture, heritage and tourism bureau. p. 45. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ↑ Adler, Elkan (4 April 2014). Jewish Travellers. Routledge. p. 61. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ↑ Chandler, Richard (1868). "Abyssinia: Mythical and Historical". The St. James's Magazine. 21. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ↑ The Ethno-History of Halaba People (PDF). p. 15. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Østebø, Terje (30 September 2011). Localising Salafism: Religious Change Among Oromo Muslims in Bale, Ethiopia. BRILL. p. 56. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Braukämper, Ulrich (2002). Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-5671-7. , page 107

- ↑ Luling, Virginia (2001). Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years. Transaction Publishers. p. 272. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ↑ Budge, E.A (1 August 2014). A History of Ethiopia: Volume I (Routledge Revivals): Nubia and Abyssinia. Routledge. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ↑ Dr. Enrico Cerulli, Documenti arabi per la storia dell’Ethiopia, Memoria della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Vol. 4, No. 2, Rome, 1931

- ↑ Crass, Joachim (2001). "The Qabena and the Wolane: Two peoples of the Gurage region and their respective histories according to their own oral traditions". Annales d'Éthiopie. 17 (1): 180. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst, An Introduction to the Economic History of Ethiopia (London: Lalibela House, 1961), p. 267.

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Borderlands (Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press, 1997), pp. 375-377

- ↑ Munro-Hay, Ethiopia, the unknown land: a cultural and historical guide (London: I.B. Tauris, 2002), p. 184

- ↑ Anthony Mockler, Haile Selassie's War (New York: Olive Branch, 2003), pp. 145, 367f

- ↑ John Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay: A personal account of the Haile Selassie years (Algonac: Reference Publications, 1984), pp. 282-287

- ↑ Libermn, Mark (2003). "LANGUAGE RELATIONSHIPS: FAMILIES, GRAFTS, PRISONS". Basic Reference. pittsburgh, USA: University Pennsylvania Academics. 28: 217–229. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ↑ Wild, Anthony (2003). "Coffee: A dark history". Basic Reference. USA: Fourth Estate. 28: 217–229. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ↑ "Climate-Data : Ethiopia". Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "local history of Ethiopia" (PDF). Nordic Africa Institute. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Wehib, Ahmed (October 2015). History of Harar and Harari (PDF). Harari people regional state, culture, heritage and tourism bureau. p. 141. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ↑ Slikkerveer (2013-10-28). Plural Medical Systems In The Horn Of Africa: The Legacy Of Sheikh Hippocrates. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781136143304.

- ↑ Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. p. 100.

- ↑ A Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa.

- ↑ "The hyena man of Harar". BBC News. 2002-07-01. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ↑ "Wild horses exist in Ethiopia, but face danger of extinction: Exploratory Team". Archived from the original on July 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Embassy staff visits Harar Brewery". Norway.org.et. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ↑ EthioNetworks.com. "Harrar Brewery, Ethiopia". Ethiopianrestaurant.com. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

Further reading

- Fritz Stuber, "Harar in Äthiopien - Hoffnungslosigkeit und Chancen der Stadterhaltung" (Harar in Ethiopia - The Hopelessness and Challenge of Urban Preservation), in: Die alte Stadt. Vierteljahreszeitschrift für Stadtgeschichte, Stadtsoziologie, Denkmalpflege und Stadtentwicklung (W. Kohlhammer Stuttgart Berlin Köln), Vol. 28, No. 4, 2001, ISSN 0170-9364, pp. 324–343, 14 ill.

- David Vô Vân, Mohammed Jami Guleid, Harar, a cultural guide, Shama Books, Addis Abeba, 2007, 99 pages

- Salma K. Jayyusi; et al., eds. (2008). "Harar: the Fourth Holy City of Islam". The City in the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. pp. 625–642. ISBN 9789004162402.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Harar. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harar. |

- Everything Harar

- Map of Harar (1936)

- List of Emirs of Adal and Harar, Royal ark website