Gezer

| גֶּזֶר | |

The Gezer High Place with massebot and basin | |

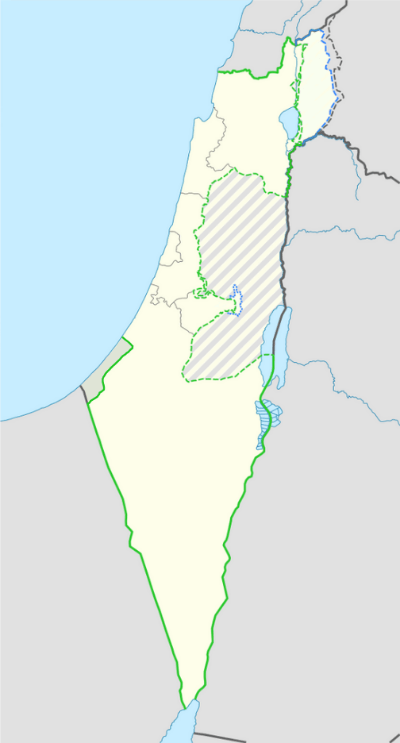

Shown within Israel | |

| Alternative name | Tel Gezer |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 31°51′32.4″N 34°55′8.4″E / 31.859000°N 34.919000°ECoordinates: 31°51′32.4″N 34°55′8.4″E / 31.859000°N 34.919000°E |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruin |

Gezer, or Tel Gezer (Hebrew: גֶּזֶר)(also Tell el-Jezer) is an archaeological site in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains at the border of the Shfela region roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. It is now an Israeli national park. In the Hebrew Bible, Gezer is associated with Joshua and Solomon.

It became a major fortified Canaanite city-state in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE. It was later destroyed by fire and rebuilt. The Amarna letters mention kings of Gezer swearing loyalty to the Egyptian Pharaoh.[1] Its importance was due in part to the strategic position it held at the crossroads of the ancient coastal trade route linking Egypt with Syria, Anatolia and Mesopotamia, and the road to Jerusalem and Jericho, both important trade routes.

In the Bible

Gezer is listed in the Book of Joshua as a Levitical city, one of ten allotted to the Levite children of Kehoth - the Kohathites (Joshua, ch. 21). Discoveries related to biblical archaeology include: a probable Canaanite high place with ten monumental megaliths (up-ended stones, each of which is called a masseba or matseva, plural massebot/matsevot; such are found elsewhere in Israel, but the Gezer massebot are the most impressive examples);[2][3][4] a double cave beneath the high place, but predating and not connected to it; 13 inscribed boundary stones, making it the first positively identified biblical city; a six-chambered gate similar to those found at Hazor and Megiddo; and a large Canaanite water system comprising a tunnel going down to a spring, similar to those found in Jerusalem, Hazor and Megiddo.

Location

Gezer was located on the northern fringe of the Shephelah region, approximately thirty kilometres northwest of Jerusalem. It was strategically situated at the junction of the Via Maris, the international coastal highway, and the highway connecting it with Jerusalem through the valley of Ayalon, or Ajalon.

Verification of the identification of this site with biblical Gezer comes from bilingual inscriptions in either Hebrew or Aramaic, and Greek, found engraved on rocks several hundred meters from the tell. These inscriptions from the 1st century BCE read "boundary of Gezer" and "of Alkios" (probably the governor of Gezer at the time).

History

Bronze Age

Early Bronze Age

Inhabitants of the first settlement at Gezer, toward the end of the 4th millennium BCE, lived in large rock-cut caves.

In the Early Bronze Age, an unfortified settlement covered the tell. It was destroyed in the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE and abandoned for several hundred years.[5]

Middle Bronze Age

In the Middle Bronze Age (first half of the 2nd millennium BCE), Gezer became a major city, well fortified[5] and containing a large cultic site.[6]

The Canaanite city was destroyed in a fire, presumably in the wake of a campaign by the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III (ruled 1479–1425 BC). The oldest known historical reference to the city is to be found on an inscription of conquered sites at Thutmose's temple at Karnak.[7]

The Tell Amarna letters, dating from the 14th century BCE, include ten letters from the kings of Gezer swearing loyalty to the Egyptian pharaoh. The city-state of Gezer (named Gazru in Babylonian) was ruled by four leaders during the 20-year period covered by the Amarna letters.[5] Discoveries of several pottery vessels, a cache of cylinder seals and a large scarab with the cartouche of Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III attest to the existence of a city at Gezer's location in the 14th century BCE - one that was apparently destroyed in that century - and suggest that the city was inhabited by Canaanites with strong ties to Egypt.[8]

- Fortifications

The tell was surrounded by a massive stone wall and towers, protected by a five meter high earthen rampart covered with plaster. The wooden city gate, near the southwestern corner of the wall, was fortified by two towers.[5]

- Cultic site with massebot

Cultic remains discovered at the site were a row of ten large standing stones, known as massebot, oriented north-south, the tallest of which was 3 meters high, with an altar-type structure in the middle, and a large, square, stone basin. The exact purpose of these megaliths is still debated, but they may have constituted a Canaanite "high place" from the Middle Bronze Age, ca. 1600 B.C.E.[6]

Late Bronze Age

In the Late Bronze Age (second half of the 2nd millennium BCE) a new fortification wall, four meters thick, was erected. In the 14th century BCE, a palace was constructed on the high western part of the tell. Toward the end of the Bronze Age, the city declined and its population diminished. Gezer is mentioned in the victory stele of Merneptah, dating from the end of the 13th century BCE.

Iron Age

In 12th-11th centuries BCE, a large building with many rooms and courtyards was situated on the acropolis. Grinding stones and grains of wheat found among the sherds indicate that it was a granary. Local and Philistine vessels attest to a mixed Canaanite/Philistine population.

Tiglath-Pileser III and the Neo-Assyrian period

The Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III put Gezer under siege between the years 734 and 732 BC.[9] The city was probably captured by the Assyrians at the end of the campaign of Tiglath-Pileser III to Canaan. A reference to Gezer may have appeared in a cuneiform relief from the 8th-century BCE royal palace of Tiglath-Pileser III at Nimrud.[7] The siege may have been the one depicted on a stone relief at the royal palace in Nimrud, where the city was called 'Gazru'.

Hellenistic period

During the Hellenistic period, Gezer was fortified by Maccabees and was ruled by the independent Jewish Hasmonean dynasty.[10]

Post-Hellenistic periods

Gezer was sparsely populated during Roman times and later times, as other regional population centers took its place.[1]

Crusader period

In 1177, the plains around Gezer were the site of the Battle of Montgisard, in which the Crusaders under Baldwin IV defeated the forces of Saladin. There was a Crusader Lordship of Montgisard and apparently a castle stood there, a short distance from Ramleh.[11]

Ottoman and modern periods

Bible: the sack of Gezer

| Siege of Gezer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Egypt | Philistines | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Siamun (?) | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Many killed | ||||||

According to the Hebrew Bible, the only source for the event, the Sack of Gezer took place at the beginning of the 10th century BCE, when the city was conquered and burned by an unnamed Egyptian pharaoh, identified by some with Siamun, during his military campaign in Palestine. This anonymous Egyptian pharaoh then gave it to King Solomon as the dowry of his daughter. Solomon then rebuilt Gezer and fortified it. The biblical story of the Israelite conquest of Canaan under their leader Joshua mentions a certain "king of Gezer" (Joshua 10:33) who had gone to help his countrymen in Lachish, where he met his death.

The Bible states:

.... King Solomon .... build .... the wall of .... Gezer (Pharaoh king of Egypt had gone up and captured Gezer and burned it with fire, and had killed the Canaanites who lived in the city, and had given it as dowry to his daughter, Solomon's wife;

— (1 Kings 9:15-16)

Identifying the pharaoh

The only mention in the Bible of a pharaoh who might be Siamun (ruled 986–967 BC) is the text from 1 Kings quoted above, and we have no other historical sources that clearly identify what really happened. As shown below, Kenneth Kitchen believes that Siamun conquered Gezer and gave it to Solomon. Others such as Paul S. Ash and Mark W. Chavalas disagree, and Chavalas states that "it is impossible to conclude which Egyptian monarch ruled concurrently with David and Solomon".[12] Professor Edward Lipinski argues that Gezer, then unfortified, was destroyed late in the 10th century (and thus not contemporary with Solomon) and that the most likely Pharaoh was Shoshenq I (ruled 943–922 BC). "The attempt at relating the destruction of Gezer to the hypothetical relationship between Siamun and Solomon cannot be justified factually, since Siamun's death precedes Solomon's accession."[13]

Archaeology

History of excavation

Archaeological excavation at Gezer has been going on since the early 1900s, and it has become one of the most excavated sites in Israel. The site was identified with ancient Gezer by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau in 1871. R. A. Stewart Macalister excavated the site between 1902 and 1909 on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. Macalister recovered several artifacts discovered several constructions and defenses. He also established Gezer's habitation strata, though due to poor stratigraphical methods, these were later found to be mostly incorrect (as well as many of his theories). Other notable archaeological expeditions to the site were made by Alan Rowe (1934), G.E. Wright, William Dever and Joe Seger between 1964 and 1974 on behalf of the Nelson Glueck School of Archaeology in the Hebrew Union College, again by Dever in 1984 and 1990, as well as the Andrews University.[7]

Excavations were renewed in June 2006 by a consortium of institutions under the direction of Steve Ortiz of the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (SWBTS) and Sam Wolff (Israel Antiquities Authority). The Tel Gezer Excavation and Publication Project is a multi-disciplinary field project investigating the Iron Age history of Gezer.

The first season of the Gezer excavations concluded successfully and revealed some interesting details. Among other things, is a discovery of thick destruction layer that may be dated to the destruction of Siamun (1 Kings 9:16).

In July 2017, archaeologists discovered skeletal remains of a family of three, one of the adults and a child wearing earrings, believed to have been killed during an Egyptian invasion in the 13th-century BCE.[14] An amulet, various scarabs and cylinder seals were also found on the site. The amulet bears the cartouches —or official royal monikers— of the Egyptian Pharaohs Thutmose III and Ramses II.

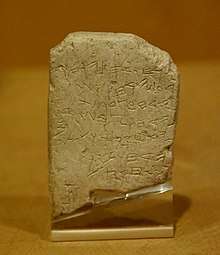

"Gezer calendar"

One of the best-known finds is the Gezer calendar. This is a plaque containing a text appearing to be either a schoolboy's memory exercises, or something designated for the collection of taxes from farmers. Another possibility is that the text was a popular folk song, or child's song, listing the months of the year according to the agricultural seasons. It has proved to be of value by informing modern researchers of ancient Middle Eastern script and language, as well as the agricultural seasons.

Israelite city gate, wall

In 1957 Yigael Yadin identified a wall and gateway very similar in construction to remains excavated at Megiddo and Hazor as Solomonic; they have since been identified as dating from the early Israelite kingdom, some centuries later.[15]

Boundary stones

13 boundary stones have been identified at the site, probably dating from the Late Hellenistic period (1st century BCE), the most recent having been found by archaeologists from SWBTS. See also Gezer#Location.

Temple of Amun

One fragmentary but well-known surviving triumphal relief scene from the Temple of Amun at Tanis believed to be related to the sack of Gezer depicts an Egyptian pharaoh smiting his enemies with a mace. According to the egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen, this pharaoh is Siamun.[16]:p. 109 Siamun appears here "in typical pose brandishing a mace to strike down prisoners(?) now lost at the right except for two arms and hands, one of which grasps a remarkable double-bladed axe by its socket."[16]:pp. 109 and 526 The writer observes that this double-bladed axe or 'halberd' has a flared crescent-shaped blade which is close in form to the Aegean influenced double axe but is quite distinct from the Canaanite double-headed axe which has a different shape that resembles an X.[16]:pp. 109–10 Thus, Kitchen concludes Siamun's foes were the Philistines who were descendants of the Aegean-based Sea Peoples and that Siamun was commemorating his recent victory over them at Gezer by depicting himself in a formal battle scene relief at the Temple in Tanis. More recently Paul S. Ash has put forward a detailed argument that Siamun's relief portrays a fictitious battle. He points out that in Egyptian reliefs Philistines are never shown holding an axe, and that there is no archaeological evidence for Philistines using axes. He also argues that there is nothing in the relief to connect it with Philistia or the Levant.[17]

See also

References

- 1 2 James F. Ross (May 1967). "Gezer in the Tell el-Amarna Letters". Jstor.org. pp. 62–70. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ "Gilat". Ngsba.org. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ "The standing stone or stele". Netours.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ David Ussishkin (2006). Czerny E., Hein I., Hunger H., Melman D., Schwab A., eds. On the History of the High Place at Gezer. Studies in Honour of Manfred Bietak, Vol. II. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 411–416. Retrieved February 2015. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "Gezer - Jewish Virtual Library". Webcache.googleusercontent.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Gezer – Ancient Importance to Israel". Allaboutarchaeology.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 Laughlin, John Charles Hugh (2006). "Gezer - Did Solomon Build a City Gate Here?". Fifty Major Cities of the Bible: From Dan To Beersheba. Routledge. pp. 127–131. ISBN 9780415223157.

- ↑ ""Hidden secret of Gezer: A pre-Solomonic city beneath the ruins"". Archived from the original on 2013-11-27. Retrieved 2013-11-27. , Haaretz, published October 24, 2013, retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ↑ Ehrlich, Carl S. (November 1996). The Philistines in Transition: A History from Ca. 1000-730 B.C.E. Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 192–193. ISBN 978-90-04-10426-6.

- ↑ Maccabees 1 13:43-48

- ↑ Jim Bradbury (2004). Montgisard, Battle of, 25 November 1177. The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Routledge. ISBN 9781134598465. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Chavalas, Mark W.; Ash, Paul S. (Spring 2001). "Review of David, Solomon and Egypt: A Reassessment by Paul S. Ash". Journal of Biblical Literature. 120 (1): 152–152. doi:10.2307/3268603. JSTOR 3268603.

- ↑ Lipinski, Edward (2006). On the Skirts of Canaan in the Iron Age (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta). Leuven, Belgium: Peeters. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-90-429-1798-9.

- ↑ Paton, C. (5 July 2017). "Israel: Ancient Human Remains Discovered in Biblical City 3,200 Years After its Destruction by the Egyptians". Newsweek. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "Gezer". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 Kitchen, K.A. (2003). On the Reliability of the Old Testament'. William B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- ↑ Ash, Paul S (November 1999). David, Solomon and Egypt: A Reassessment (JSOT Supplement). Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 38–46. ISBN 978-1-84127-021-0.

Further reading

- William G. Dever, Gezer Revisited: New Excavations of the Solomonic and Assyrian Period Defenses, The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 47, No. 4 (Dec., 1984), pp. 206–218

- Dever, William G., "Visiting the Real Gezer: A Reply to Israel Finkelstein", Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, Volume 30, Number 2, September 2003, pp. 259–282(24)

- "Confronting the Past: Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel", Seymour Gitin, (ed), Eisenbrauns, (January 2006), ISBN 978-1-57506-117-7

- Macalister, R. A. Stewart (1912). The Excavation of Gezer: 1902 - 1905 and 1907 - 1909 (PDF). John Murray, Albemarle Street West, London.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gezer. |