Genetic studies on Bosniaks

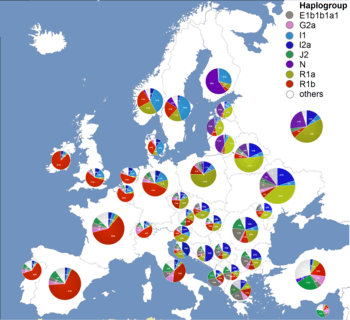

As with all modern European nations, a large degree of 'biological continuity' exists between the Bosniaks and their ancient predecessors with Bosniak Y chromosomal lineages testifying to predominantly Paleolithic European ancestry.[1][2] A majority (>67%) of Bosniaks belong to one of the three major European Y-DNA haplogroups:[1] I (48.2%), R1a (15.3%) and R1b (3.5%), while a minority belongs to less frequently occurring haplogroups E (12.9%), J2 (9.5%), G (3.5%) and F (3.5%) along with other more rare lineages.[1]

These studies have indicated the dominant Y-DNA haplogroup I, and specifically its sub-haplogroup I2 found in Bosniaks, to be associated with paleolithic settlers as attributed to the ancient populations that expanded into the Balkans following the Last Glacial Maximum some 21,000 years ago.[1] Peričić et al. for instance places its expansion to have occurred "not earlier than the YD to Holocene transition and not later than the early Neolithic".[2] Decidedly, the Slavic population can be divided into two genetically distinct groups: one encompassing all Western-Slavic (Poles, Slovaks etc.), Eastern-Slavic (Russians, Ukrainians etc.), and a few Southern-Slavic populations (north-western Croats and Slovenes), characterized by Haplogroup R1a, and one encompassing all remaining Southern Slavs (including Bosniaks), characterized by Haplogroup I2a2 (I-L69.2). According to Rebała et al., this phenomenon is explained by "contribution of the Y chromosomes of peoples who settled in the region before the Slavic expansion to the genetic heritage of Southern Slavs."[3] Studies based on bi-allelic markers of the NRY (non-recombining region of the Y-chromosome) have shown the three main ethnic groups of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats) to share, in spite of some quantitative differences, a large fraction of the same ancient gene pool distinct for the region.[4] Analysis of autosomal STRs have moreover revealed no significant difference between the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina and neighbouring populations.[5]

Y-chromosomal haplogroups identified among the Bosniaks from Bosnia and Herzegovina are the following:

- I2, 43.50%.[1] The frequency of this haplogroup peaks in Bosnia and Herzegovina (52.20% and 63.80%, by respective region[2]), and its variance peaks over a large geographic area covering B-H, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, Northern Albania, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine and Belarus. This haplogroup is associated with paleolithic[6] settlement in the region and as a likely signature of a Balkan population re-expansion after the Last Glacial Maximum.[1]

- I1, 4.70%.[1] Men belonging to this haplogroup all descend from a single ancestor who lived in Northern Europe between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago. It is the most common haplogroup in Northern Europe, reaching over 40% of the population in Scandinavia, where it also evolved in isolation during the late Paleolithic and Mesolithic.[7] Traces of this paternal lineage appear in the areas the Germanic tribes were recorded as having invaded or migrated to.[8][9] The frequency of haplogroup I1 in western Balkans (or Balkans in general) hints at had a particularly strong Gothic and Gepid presence, which is concordant with the establishment of the Ostrogothic kingdom in the 5th century AD.

- R1a-M17, 15.30%.[1] The first major expansion of haplogroup R1a took place with the westward propagation of the Corded Ware (or Battle Axe) culture (2800–1800 BCE) from the northern forest-steppe in the Yamna homeland. R1a is thought to have been the dominant haplogroup among the northern and eastern Proto-Indo-European language speakers. The frequency of this haplogroup peaks today in Belarus and Ukraine, and its variance peaks in northern Bosnia and Herzegovina (with 24.60% and 12.06%, by respective region[2]). It is the most predominant Y-chromosomal haplogroup in the overall Slavic gene pool.[1][2] The variance of R1a1 in the Balkans might have been enhanced by infiltrations of Indo-European speaking peoples between 2000 and 1000 BC, and by the Slavic migrations to the region in the early Middle Ages.[1][2]

- E1b1b1a2-V13, 12.90%.[1] E-V13 is one of the major markers of the Neolithic diffusion of farming from the Balkans to rest of the Europe. Its frequency is now far higher in Greece, South Italy and the Balkans.[2][10] The modern distribution of E-V13 hints at a strong correlation with the Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures of Old Europe, such as the Vinča and Karanovo cultures. E-V13 was later associated with the ancient Greek expansion and colonisation. Outside of the Balkans and Central Europe, it is particularly common in southern Italy, Cyprus and southern France, all part of the Classical ancient Greek world. The current distribution of this lineage might be the result of several demographic expansions from the Balkans, such as that associated with the Neolithic revolution, the Balkan Bronze Age, and more recently, during the Roman era during the so-called "rise of Illyrican soldiery".[2]

- J2a-M410, 7.10%[1] Various other lineages of haplogroup J2-M172 are found throughout the Balkans, all with low frequencies. Haplogroup J and all its descendants originated in the Middle East. It is proposed that the Balkan Mesolithic foragers, bearers of I-P37.2 and E-V13, adopted farming from the initial J2 agriculturalists who colonized the region about 7000 to 8000 ybp, transmitting the Neolithic cultural package.[10]

- R1b-M269, 3.50%.[1] Haplogroup R1b is the most common haplogroup in Western Europe, reaching over 80% of the population in Ireland, western Wales and the Basque country. This haplogroup was probably introduced to Europe by farmers migrating from western Anatolia, probably about 7500 years ago and is present in low-to moderate frequencies in Balkan Slavs, and certain in Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats (2.20% and in Bosnia and Herzegovina in general approximately 4%).[11]

- G-M201, 3.50%[1] It has been proven by the testing of Neolithic remains in various parts of Europe that haplogroup G2a was one of the lineages of Neolithic farmers and herders who migrated from Anatolia to Europe between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago.[12]

- F*-M89, 3.50%[1]

- J2b-M102, 2.40%[1] J2b seems to have a stronger association with the Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures of Southeast Europe. It is particularly common in the Balkans, Central Europe and Italy, which is roughly the extent of the European Copper Age culture. Its maximum frequency is achieved around Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro and Northwest Greece – the part of the Balkans which best resisted the Slavic invasions in the Early Middle Ages.

- J1-M267, 2.40%[1] Haplogroup J1 is a Middle Eastern haplogroup, which probably originated in eastern Anatolia. This haplogroup is almost certainly linked to the expansion of pastoralist lifestyle throughout the Middle East and Europe. J1 is particularly common in mountainous regions of Europe (with the notable exception of the Alps and the Carpathians), like Caucasus, Greece, Albania, Italy, central France, and the most rugged parts of Iberia.

- T-M184, 1.20%[1] The modern distribution T in Europe strongly correlates with the Neolithic colonisation of Mediterranean Europe by Near-Eastern farmers, notably the Cardium Pottery culture (5000–1500 BCE).

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Marjanovic, D., et al. (2005) "The Peopling of Modern Bosnia-Herzegovina: Y-chromosome Haplogroups in the Three Main Ethnic Groups". Annals of Human Genetics 69. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00190.x PMID 16266413.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pericić M, Lauc LB, Klarić IM, Rootsi S, Janićijevic B, Rudan I, Terzić R, Colak I, et al. (2005). "High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations". Mol. Biol. Evol. 22 (10): 1964–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

N.B. The haplogroups' names in the section "Genetics" are according to the nomenclature adopted in 2008, as represented in Vincenza Battaglia (2008) Figure 2, so they may differ from the corresponding names in Peričić (2005). - ↑ Rebała K., et al. (2007). Y-STR variation among Slavs: evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin. J Hum Genet. 2007;52(5):406-14, p. 411. Epub 2007 Mar 16.

- ↑ Damir, Marjanović / International Congress Series 1288 (2006) 243-245; et al. (2006). "Preliminary population study at fifteen autosomal and twelve Y-chromosome short tandem repeat loci in the representative sample of multinational Bosnia and Herzegovina residents" (PDF). Institute for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology: 244.

- ↑ Damir, Marjanović / International Congress Series 1288 (2006) 243-245; et al. (2006). "Preliminary population study at fifteen autosomal and twelve Y-chromosome short tandem repeat loci in the representative sample of multinational Bosnia and Herzegovina residents" (PDF). Institute for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology: 245.

- ↑ Rootsi et al. Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75:128–137, 2004.

- ↑ Peter A. Underhill et al., New Phylogenetic Relationships for Y-chromosome Haplogroup I: Reappraising its Phylogeography and Prehistory, in Rethinking the Human Revolution (2007), pp. 33–42. P. Mellars, K. Boyle, O. Bar-Yosef, C. Stringer (Eds.) McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK.

- ↑ Genographic Project of National Geographic

- ↑ "New Phylogenetic Relationships for Y-chromosome Haplogroup I: Reappraising its Phylogeography and Prehistory," Rethinking the Human Evolution, Mellars P, Boyle K, Bar-Yosef O, Stringer C, Eds. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK, 2007, pp. 33–42 by Underhill PA, Myres NM, Rootsi S, Chow CT, Lin AA, Otillar RP, King R, Zhivotovsky LA, Balanovsky O, Pshenichnov A, Ritchie KH, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Kivisild T, Villems R, Woodward SR

- 1 2 Battaglia, Vincenza; et al. (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 6. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

- ↑ Marjanović, Damir; et al.

- ↑ "Frequencies of prehistoric mtDNA and Y-DNA from the European Paleolithic to the Iron Age – Eupedia". Eupedia. Retrieved 1 May 2016.