France–Germany relations

.svg.png) | |

France |

Germany |

|---|---|

The relations between France and Germany, since 1871, according to Ulrich Krotz,[1] has three grand periods: 'hereditary enmity' (down to 1945), 'reconciliation' (1945–63) and since 1963 the 'special relationship' embodied in a cooperation called Franco-German Friendship (French: Amitié franco-allemande; German: Deutsch-Französische Freundschaft).[2]

In the context of the European Union, the cooperation between the two countries is immense and intimate. Even though France has at times been eurosceptical in outlook, especially under President Charles de Gaulle, Franco-German agreements and cooperations have always been key to furthering the ideals of European integration.

In recent times, France and Germany are among the most enthusiastic proponents of the further integration of the EU. They are sometimes described as the "twin engine" or "core countries" pushing for moves.[3] A tram straddling the Franco-German border, across the river Rhine from Strasbourg to Kehl, was inaugurated on the 28th of April 2017 symbolising the strength of relation between the two countries.[4]

Country comparison

| Population | 67,087,000 | 82,066,000 |

| Area | 674,843 km2 (260,558 sq mi) | 357,021 km2 (137,847 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 116/km2 (301/sq mi) | 229/km2 (593/sq mi) |

| Capital | Paris | Berlin |

| Largest City | Paris – 2,234,105 (12,161,542 Metro) | Berlin – 3,510,032 (5,964,002 Metro) |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic | Federal parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Official language | French (de facto and de jure) | German (de facto and de jure) |

| Main religions | 58% Christianity, 31% non-religious, 7% Islam, 1% Judaism, 1% Buddhism, 2% other |

58% Christianity, 37% non-religious, 4% Islam, 1% other[5] |

| Ethnic groups | 86% French, 7% other European, 7% North African, other Sub-Saharan African, Indochinese, Asian, Latin American and Pacific Islander. |

80% Germans, 5% Turks, 5% other Europeans, 10% other |

| GDP (PPP) | $2.590 trillion, $41,375 per capita | $3.615 trillion, $44,888 per capita |

| GDP (nominal) | $2.846 trillion, $44,538 per capita | $3.730 trillion, $45,091 per capita |

| Expatriate populations | 110,881 French citizens lived in Germany on Dec. 31, 2012[6] | 130,742[7] German citizens lived in France in 2012[8] |

| Military expenditures | $62.5 billion | $46.7 billion |

History

Early interactions

Both France and Germany track their history back to the time of Charlemagne, whose vast empire included most of the area of both modern-day France and Germany – as well as the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, and northern Italy.

The death of Charlemagne's son Louis the Pious and the following partition of the Frankish Empire in the 843 Treaty of Verdun marked the end of a single state. While the population in both the Western and Eastern kingdoms had relative homogeneous language groups (Gallo-Romanic in West Francia, and Low German and High German in East Francia), Middle Francia was a mere strip of a mostly blurring yet culturally rich language-border-area, roughly between the rivers Meuse and Rhine – and soon partitioned again. After the 880 Treaty of Ribemont, the border between the western and eastern kingdoms remained almost unchanged for some 600 years. Germany went on with a centuries-long attachment with Italy, while France grew into deeper relations with England.

Despite a gradual cultural alienation during the High and Late Middle Ages, social and cultural interrelations remained present through the preeminence of Latin language and Frankish clergy and nobility.

France and Habsburgs

The later Emperor Charles V, a member of the Austrian House of Habsburg, inherited the Low Countries and the Franche-Comté in 1506. When he also inherited Spain in 1516, France was surrounded by Habsburg territories and felt under pressure. The resulting tension between the two powers caused a number of conflicts such as the War of the Spanish Succession, until the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 made them allies against Prussia.

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), devastating large parts of the Holy Roman Empire, fell into this period. Although the war was mostly a conflict between Protestants and Catholics, Catholic France sided with the Protestants against the Austrian-led Catholic Imperial forces. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 gave France part of Alsace. The 1679 Treaties of Nijmegen consolidated this result by bringing several towns under French control. In 1681, Louis XIV marched into the city of Strasbourg on September 30, and proclaimed its annexation.[9]

Meanwhile, the expanding Muslim Ottoman Empire became a serious threat to Austria. The Vatican initiated a so-called Holy League against the "hereditary enemy" of Christian Europe ("Erbfeind christlichen Namens"). Far from joining or supporting the common effort of Austria, Germany and Poland, France under Louis XIV of France invaded the Spanish Netherlands in September 1683, a few days before the Battle of Vienna. While Austria was occupied with the Great Turkish War (1683–1699), France initiated the War of the Grand Alliance (1688–1697). The attempt to conquer large parts of southern Germany ultimately failed when German troops were withdrawn from the Ottoman border and moved to the region. However, following a scorched earth policy that caused a large public outcry at the time, French troops devastated large parts of the Palatinate, burning down and levelling numerous cities and towns in southern Germany.

France and Prussia

In the 18th century, the rise of Prussia as a new German power caused the Diplomatic Revolution and an alliance between France, Habsburg and Russia, manifested in 1756 in the Treaty of Versailles and the Seven Years' War against Prussia and Great Britain. Although a German national state was on the horizon, the loyalties of the German population were primarily with smaller states. The French war against Prussia was justified through its role as guarantor of the Peace of Westphalia, and it was in fact fighting on the side of the majority of German states.

Frederick the Great led the defense of Prussia for 7 years, and though heavily outnumbered, defeated his French and Austrian invaders. Prussia and France clashed multiple times, and many more times than the other countries. This started years of hatred between the two countries. Frederick the Great was soon respected by all of his enemies, and Napoleon himself used him as a model for battle.

The civil population still regarded war as a conflict between their authorities, and did not so much distinguish between troops according to the side on which they fought but rather according to how they treated the local population. The personal contacts and mutual respect between French and Prussian officers did not stop entirely while they were fighting each other, and the war resulted in a great deal of cultural exchange between French occupiers and German population.

Impact of French Revolution and Napoleon

German nationalism emerged as a strong force after 1807 as Napoleon conquered much of Germany and brought in the new ideals of the French Revolution. The French mass conscription for the Revolutionary Wars and the beginning formation of nation states in Europe made war increasingly a conflict between peoples rather than a conflict between authorities carried out on the backs of their subjects.

Napoleon put an end to the millennium-old Holy Roman Empire in 1806, forming his own Confederation of the Rhine, and reshaped the political map of the German states, which were still divided. The wars, often fought in Germany and with Germans on both sides as in the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig, also marked the beginning of what was explicitly called French–German hereditary enmity. Napoleon directly incorporated German-speaking areas such as the Rhineland and Hamburg into his First French Empire and treated the monarchs of the remaining German states as vassals. Modern German nationalism was born in opposition to French domination under Napoleon. In the recasting of the map of Europe after Napoleon's defeat, the German-speaking territories in the Rhineland adjoining France were put under the rule of Prussia.

France and Bavaria

Bavaria as the third-largest state in Germany after 1815 enjoyed much warmer relations with France than the larger Prussia or Austria. From 1670 onwards the two countries were allies for almost a century, primarily to counter Habsburg ambitions to incorporate Bavaria into Austria. This alliance was renewed after the rise of Napoleon to power with a friendship treaty in 1801 and a formal alliance in August 1805, pushed for by the Bavarian Minister Maximilian von Montgelas. With French support Bavaria was elevated to the status of a Kingdom in 1806. Bavaria supplied 30,000 troops for the invasion of Russia in 1812, of which very few returned. With the decline of the First French Empire Bavaria opted to switch sides on 8 October 1813 and left the French alliance in favour of an Austrian one through the Treaty of Ried.[10][11]

Nineteenth century

During the first half of the 19th century, many Germans looked forward to a unification of the German states; one issue was whether Catholic Austria would be a part. German nationalists believed that a united Germany would replace France as the world's dominant land power. This argument was aided by demographic changes: since the Middle Ages, France had had the largest population in Western Europe, but in the 19th century its population stagnated (a trend which continued until the second half of the 20th century), and the population of the German states overtook it and continued to rapidly increase.[12]

The eventual unification of Germany was triggered by the Franco-German War in 1870 and subsequent French defeat. German forces crushed the French armies at the Battle of Sedan. Finally, in the Treaty of Frankfurt, reached after a lengthy siege of Paris, France was forced to cede the mostly Germanic-speaking Alsace-Lorraine territory (consisting of most of Alsace and a quarter of Lorraine), and pay an indemnity of five billion francs. Thereafter, Germany was the leading land power.[13]

Bismarck's main mistake was giving into the Army and to intense public demand in Germany for acquisition of the border provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, thereby turning France into a permanent, deeply-committed enemy. see French–German enmity Theodore Zeldin says, "Revenge and the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine became a principal object of French policy for the next forty years. That Germany was France's enemy became the basic fact of international relations."[14] Bismarck's solution was to make France a pariah nation, encouraging royalty to ridicule its new republican status, and building complex alliances with the other major powers – Austria, Russia, and Britain – to keep France isolated diplomatically.[15][16]

The issue of Alsace-Lorraine faded in importance after 1880, but the rapid growth in the population and economy of Germany left France increasingly far behind. In the 1890s relationships remained good as Germany supported France during its difficulties with Britain over African colonies. Any lingering harmony collapsed in 1905, when Germany took an aggressively hostile position to French claims to Morocco. There was talk of war and France strengthened its ties with Britain and Russia.[17]

First World War

The long-term French reaction to defeat in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71 was Revanchism: a deep sense of bitterness, hatred and demand for revenge against Germany, especially because of the loss of Alsace and Lorraine.[18] Paintings that emphasized the humiliation of the defeat came in high demand, such as those by Alphonse de Neuville.[19]

French foreign policy was based on a fear that Germany was larger and steadily growing more powerful.[20] Apart perhaps from the German threat, most Frenchmen ignored foreign affairs and colonial issues. In 1914 the chief pressure group was the Parti colonial, a coalition of 50 organizations with a combined total of 5000 members.[21] The issue of Alsace-Lorraine faded in importance after 1880 with the decline of the monarchist element but when war broke out in 1914, recovery of the two lost provinces became France's primary war aim.[22]

After Bismarck's removal in 1890, French efforts to isolate Germany became successful; with the formation of the Triple Entente, Germany began to feel encircled.[23] Foreign minister Delcassé, especially, went to great pains to woo Russia and Great Britain. Key markers were the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, the 1904 Entente Cordiale with Great Britain, and finally the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907 which became the Triple Entente. This formal alliance with Russia, and informal alignment with Britain, against Germany and Austria eventually led Russia and Britain to enter World War I as France's Allies.[24][25]

1920s

The Allied victory saw France regain Alsace-Lorraine and briefly resume its old position as the leading land power on the European continent. France was the leading proponent of harsh peace terms against Germany at the Paris Peace Conference. Since the war had been fought on French soil, it had destroyed much of French infrastructure and industry, and France had suffered the highest number of casualties proportionate to population. Much French opinion wanted the Rhineland, the section of Germany adjoining France and the old focus of French ambition, to be detached from Germany as an independent country; in the end they settled for a promise that the Rhineland would be demilitarized, and heavy German reparation payments. On the remote Eastern end of the German Empire, the Memel territory was separated from the rest of East Prussia and occupied by France before being annexed by Lithuania. To alleged German failure to pay reparations under the Treaty of Versailles in 1923, France responded with the occupation of the Rhineland and the industrial Ruhr area of Germany, the center of German coal and steel production, until 1925. Also, the French-dominated International Olympic Committee banned Germany from the Olympic Games of 1920 and 1924, which illustrates French desire to isolate Germany.

Locarno treaties of 1925

In late 1924 German foreign minister Gustav Stresemann made his highest priority the restoration of German prestige and privileges as a leading European nation. French withdrawal from the occupation of the Ruhr was scheduled for January 1925, but Stresemann sensed that France was very nervous about its security and might cancel the withdrawal. He realized that France deeply desired a British guarantee of its postwar borders, but that London was reluctant. Stresemann came up with a plan whereby all sides would get what they wanted through a series of guarantees set out in a series of treaties. British Foreign Minister Austen Chamberlain enthusiastically agreed. France realized that its occupation of the Ruhr Had caused more financial and diplomatic damage that was worth, went along with the plan. The conference of foreign ministers they convened in the Swiss resort of Locarno and agreed on a plan. The first treaty was the most critical one: a mutual guarantee of the frontiers of Belgium, France, and Germany, which was guaranteed by Britain and Italy. The second and third treaties called for arbitration between Germany and Belgium, and Germany and France, regarding future disputes. The fourth and fifth were similar arbitration treaties between Germany and Poland, and Germany and Czechoslovakia. Poland especially, and Czechoslovakia as well, felt threatened by the Locarno agreements and these treaties were attempts to reassure them. Thanks to the Dawes plan, Germany was now making regular reparations payments. The success of the Locarno agreements Led to the admission of Germany to the League of Nations. In September 1926, with a seat on its counsel as a permanent member. The result was the euphoric "Spirit of Locarno" across Europe—a sense that it was possible to achieve peace and a permanent system of guaranteeing that peace.[26]

1930s

The Great Depression on 1929-33 soured the mood in France, and plunged Germany into economic hardship and violent internal convulsions and upheavals. From 1933 under Adolf Hitler, Germany began to pursue an aggressive policy in Europe. Meanwhile, France in the 1930s was tired, politically divided, and above all dreaded another war, which the French feared would again be fought on their soil for the third time, and again destroy a large percentage of their young men. France's stagnant population meant that it would find it difficult to withhold the sheer force of numbers of a German invasion; it was estimated Germany could put two men of fighting age in the field for every French soldier. Thus in the 1930s the French, with their British allies, pursued a policy of appeasement of Germany, failing to respond to the remilitarization of the Rhineland, although this put the German army on a larger stretch of the French border.

Second World War

Finally, however, Hitler pushed France and Britain too far, and they jointly declared war when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. But France remained exhausted and in no mood for a rerun of 1914–18. There was little enthusiasm and much dread in France at the prospect of actual warfare after the “phony war”. When the Germans launched their blitzkrieg invasion of France in 1940, the French Army crumbled within weeks, and with Britain retreating, an atmosphere of humiliation and defeat swept France.

A new government under Marshal Philippe Pétain surrendered, and German forces occupied most of the country. A minority of the French forces escaped abroad and continued the fight under General Charles de Gaulle (the “Free French” or “Fighting French”). On the other hand, the French Resistance conducted sabotage operations inside German-occupied France. To support the invasion of Normandy of 1944, various groups increased their sabotage and guerrilla attacks; organizations such as the Maquis derailed trains, blew up ammunition depots, and ambushed Germans, for instance at Tulle. The 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich came under constant attack and sabotage on their way across the country to Normandy, suspected the village of Oradour-sur-Glane of harboring terrorists, arms and explosives. In retaliation they decided to shoot all men, and burn alive all women and children in the church.

There was also a free French army fighting with the Allies, numbering almost five hundred thousand men by June 1944, one million by December and 1.3 million by the end of the war. By the war's end, the French army occupied south-west Germany and a part of Austria.

France, Germany, and United Europe

The onset of first sights of France-German cooperation

Marshal Petain who was one of the first military leaders of Vichy France during the Second World War adopted the ideology of National Revolution which was originally based on a pro-German idea which had been known widely in the 1930s. At that time Germany worked hard to spread it widely in Europe.

When the Franco-German reconciliation committee "Comité France-Allemagne" founded in 1935 in Paris it was an important element for Germany to get closer to France, views of Pro-European, Pro-German, anti British, anti liberal political and economic views and some times Pro-Nazi views was adopted by this Committee. Later on the key members of the Committee became the key leaders of the French collaborators with Nazis after 1940.

When Marshal Petain officially proclaimed the collaboration policy with Nazi Germany in June 1941, he justified it to the French people as an essential need for the New European Order and to keep the unity of France. Therefore, much of WW2 French propaganda was pro-European, exactly as German propaganda was. Therefore, a group called "Group Collaboration" had been established during the war in France, and led a myriad of conferences promoting Pro-Europeanism. The very first time the expression "European Community" was used was at its first sessions, as well as many conferences and guests lectures sponsored by the German government, propagating French-German reconciliation, French renewal and European solidarity.

Post war Europe

The war left Europe in a weak position and divided between the United States and the Soviet Union. For the first time in the history of Europe both Americans and Soviets had a strategic foothold on the continent. Defeated Germany had American, British, French and Soviet troops in its territory and was divided into zones of occupation by the victorious powers. Soviet troops remained in those countries in Eastern Europe that had been liberated by the Red Army from the Nazis. The American troops also remained on the territory of the member countries which became later members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation.

The shape of western Europe was imposed by the events which occurred from 1945-50. Thus, there was a core of allied countries which recognized their ultimate dependence on each other and on the fate of Western Germany, a group of surrounding neutrals which were sharply isolated by the 'iron curtain' for their cooperation with eastern powers and an outer group of more reluctant allies. This political geography imposed post war remained in place for decades; later on it witnessed a significant modification.

Western European countries were also in urgent need of financial aid to recover and develop their economies that had been destroyed during the war. In addition to that, Western Europeans at that time were looking to achieve the economic performance of the United States. In contrast, the above-mentioned reasons were the major motivation for Western European countries to integrate after World War II.

It has been argued that the then United States Secretary of State, George Marshall made his eponymous plan in June 1947 to bring about the division of western Europe from the east, and promote integration within western Europe, and additionally encouraged the preparation of an organization which can administer this aid. This led to the establishment of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) in 1948.

The bases of the Franco-German Cooperation in the EU

Earlier in 1948, there were significant key leaders in the French civil service who favoured an agreement with the Germans as well as an integrated Europe that would include Germany. The French European Department was working on a coal and steel agreement for the Ruhr-Lorraine-Luxembourg area, with equal rights for all. One French civil servant recommended 'laying down the bases of a Franco-German economic and political association that would slowly become integrated into the framework of the evolving Western organization'. Deighton strongly illustrated that the French leaders sought the cooperation with the Germans as key factor on the path of integrated Europe.

As a sequence, Jean Monnet, who has been described as the founder father and the chief architect of European Unity, announced the French Schuman plan of 9 May 1950, which led to the founding a year later of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The plan brought the reconciliation of France and Germany, the axis of political European integration, furthermore, the plan announced the proposal of a European army. This led to the signing of the treaty of the European Defence Community (EDC) in 1952. The main purpose of establishing such army was to create a "European security identity", through closer Franco-German military and security cooperation.

In like manner, the German minister of economics Ludwig Erhard, created a significant evolution in the German economy and a durable, well established trading relationship between the Federal Republic and its European neighbours as well. Later on when the Treaty of Rome came into action in 1958, it took the responsibility to strengthen and sustain the new political and economic relationships that had developed between the German nation and its former victims in Western Europe. The treaty beside it included side deals; it created a customs union and established the rules needed to make the competition mechanism work properly.

As a sequence of this, booming European economies, fired by Germany, led to the formation of the new customs union known as the European Economic Community (EEC). But it did not go well as the organization of Europe, because only the members of the coal and steel community 'ECSC' (" the six": Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany) joined the EEC. Seven of the remaining nations belonging to the Organization of European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) which administered the Marshall Plan, did not join the EEC but instead formed an alternative body, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). It was a free trade area as opposed to a customs union with common external tariffs and a political agenda, competing with the EEC as it was remarkably successful.

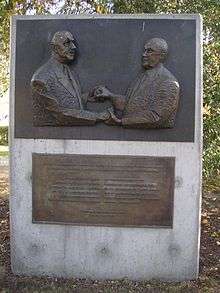

Friendship

With the threat of the Soviet Union during the Cold War, West Germany sought its national security in the re-integration into Western Europe, while France sought after a re-establishment as a Grande Nation. The post-war Franco-German cooperation is based on the Élysée Treaty, which was signed by Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer on January 22, 1963.[27] The treaty contained a number of agreements for joint cooperation in foreign policy, economic and military integration and exchange of student education.

The treaty was signed under difficult political situations at that time and criticized both by opposition parties in France and Germany, as well as from the United Kingdom and the United States. Opposition from the United Kingdom and the United States was answered by an added preamble which postulated a close cooperation with those (including NATO) and a targeted German reunification.

The treaty achieved a lot in initiating European integration and a stronger Franco-German co-position in transatlantic relations.

The initial concept for the Franco-German cooperation however dates back a lot further than the Elysée Treaty and is based on the overcoming the centuries of Franco-German hostilities within Europe. It was compared to a re-establishment of Charlemagne's European empire as it existed before division by the Treaty of Verdun in 843 AD.

The Schuman declaration of 1950 is regarded by some as the founding of Franco-German cooperation, as well as of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) of 1951, which also included Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

The cooperation was accompanied by strong personal alliance in various degrees:

Alliances

Political alliances

As early as 1994 - a time of the EU12 - the German Christian Democrats Wolfgang Schäuble and Karl Lamers published a pamphlet in which they called for a Kerneuropa (= core Europe). This came in response to a slowing down of European integration by eurosceptic member states while many Europeans in "core Europe" states ask for a stronger Europe. Those countries typically include France, Germany and the Benelux, as well as Austria, Spain and Italy. The core Europe idea envisaged that it would have a 'centripetal effect', a magnetic attraction for the rest of Europe.

Yet, the emergence of the envisaged "core social Europe" has become highly unlikely - the original Schäuble-Lamers idea of multi-speed Europe has since been replaced by the concept of a variable geometry Europe which is formally represented in the political instrument of enhanced co-operation. Additionally the core Europe policy would contradict the structural reform agenda that has marked the German social-democratic government and would also be at odds with Berlin's general support for further enlargement. France has also expressed that any factual split would be in contradiction to the EU ideals thereby risking the completion of an EU super nation encompassing the whole of Europe.

Other practical problems of a possible core Europe are that France and Germany find it hard to establish agreement within various policy areas. Both countries want to strengthen European defence forces, but Germany is cutting its defence spending. Both France and Germany would like to boost the EU's foreign policy, but France no longer supports Germany's call for majority voting in foreign policy. On asylum and migration policies, the two countries have quite different approaches, and progress in other areas of justice and home affairs has been slow.

However the two countries manage a common European policy in regard to European integration and also foreign affairs, a strong example of this is the Iraq War that aligned the Franco-German alliance with Russia and China in opposition to American and British foreign policy. The political differences around the Iraq War 2003 have also been influential on the creation of the G6 (EU) conferences that may be regarded as the new motor to align the views on foreign affairs and European integration.

Former French President Jacques Chirac has stated his desire to see Europe as a counterweight to American power against what some see as increasingly predatory American politics in the Middle East.

On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Élysée Treaty in 2003, the EU Commissioners Pascal Lamy (France) and Günter Verheugen (Germany) presented the so-called Lamy-Verheugen Plan that proposes a factual unification of France and Germany in some important areas - including unified armed forces, combined embassies and a shared seat at the United Nations Security Council. Starting off that date the ministers were encouraged to maintain direct contact with a biannual joint Franco-German Ministerial Council held in the following years.

On 3 August 2014, French President Francois Hollande and German President Joachim Gauck together marked the centenary of Germany's declaration of war on France by laying the first stone of a memorial in Vieil Armand, France, known in German as Hartmannswillerkopf, for French and German soldiers killed in World War I.[28]

Economic alliances

- European Space Agency (with many other European states)

- EADS (with two CEOs)

- Airbus (also present in the UK and Spain)

Franco-German collaborative enterprises include;

Cultural alliances

- Promotion of French and German language in both countries (See Alsace).

- Creation of a joint Franco-German History Coursebook to promote a "shared vision of History"

- The Franco-German University was created in 1999 to enable cooperation in tertiary education.[29]

- Arte, Franco-German cultural TV-channel

Military alliances

- From its inception during the 1960s the Eurocorps has contained large contingents of French and German troops at its core, while other EU nations have contributed soldiers to the multinational force. As well as the Franco-German Brigade the remainder of the corps takes much of its infantry from France and much of its armour from Germany.

See also

- French–German enmity

- List of Ambassadors of France to Germany

- Causes of World War II

- International relations (1814–1919)

- France–United Kingdom relations

- Germany–United Kingdom relations

- France–United States relations

- Germany–United States relations

- Foreign relations of France

- Foreign relations of Germany

- History of Europe

- Paris Peace Conference, 1919

Notes and references

- ↑ http://www.eui.eu/DepartmentsAndCentres/PoliticalAndSocialSciences/People/Professors/Krotz.aspx

- ↑ Ulrich Krotz, "Three eras and possible futures: a long-term view on the Franco-German relationship a century after the First World War," International Affairs (March 2014) 90#2 pp 337-350. online

- ↑ See for instance Loke Hoe Yeong, "50 years of the ‘twin engine’ - Franco-German reconciliation, European integration and reflections for Asia", EU center in Singapore, March 2013

- ↑ Posaner, Joshua (29 April 2017). "Strasbourg's eurotram aims to boost Franco-German axis". Politico. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ Religionszugehörigkeit, Deutschland Archived 2015-12-25 at the Wayback Machine., fowid.de (in German)

- ↑ Les Français établis hors de France - Population française inscrite au 31 décembre 2012 Archived 2013-02-01 at the Wayback Machine., France Diplomatie

- ↑ http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/dossiers-pays/allemagne/presentation-de-l-allemagne/

- ↑ Répartition des étrangers par nationalité, Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (Insee)

- ↑ John A. Lynn, The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 163.

- ↑ Der große Schritt nach vorne (in German) Bayerischer Rundfunk, published: 27 April 2015, accessed: 20 October 2015

- ↑ Early Modern Germany, 1477-1806 Google book review, author: Michael Hughes, accessed: 20 October 2015

- ↑ G. P. Gooch, Franco-German relations, 1871–1914 (1923).

- ↑ Norman Rich, Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914 (1993), pp 184-250.

- ↑ Theodore Zeldin, France, 1848–1945: Volume II: Intellect, Taste, and Anxiety (1977) 2: 117.

- ↑ Carlton J. H. Hayes, A Generation of Materialism, 1871–1900 (1941), pp 1-2.

- ↑ Mark Hewitson, "Germany and France before the First World War: A Reassessment of Wilhelmine Foreign Policy" English Historical Review (2000) 115#462 pp. 570-606 in JSTOR

- ↑ J.F.V. Keiger, France and the World since 1870 (2001) pp 112-17

- ↑ Karine Varley, "The Taboos of Defeat: Unmentionable Memories of the Franco-Prussian War in France, 1870–1914." in Jenny Macleod, ed., Defeat and Memory: Cultural Histories of Military Defeat in the Modern Era (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) pp. 62-80; also Karine Varley, Under the Shadow of Defeat: The War of 1870-71 in French Memory (2008)

- ↑ Robert Jay, "Alphonse de Neuville's 'The Spy' and the Legacy of the Franco-Prussian War," Metropolitan Museum Journal (1984) 19: pp. 151-162 in JSTOR

- ↑ Margaret Macmillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013) ch 6

- ↑ Anthony Adamthwaite, Grandeur and Misery: France's Bid for Power in Europe, 1914-1940 (1995) p 6

- ↑ Frederic H. Seager, "The Alsace-Lorraine Question in France, 1871–1914." in Charles K. Warner, ed., From the Ancien Regime to the Popular Front (1969): 111-126.

- ↑ Samuel R. Williamson Jr"German Perceptions of the Triple Entente after 1911: Their Mounting Apprehensions Reconsidered" Foreign Policy Analysis 7.2 (2011): 205-214.

- ↑ Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918 (1954) pp 345, 403–26

- ↑ G.P. Gooch, Before the war: studies in diplomacy (1936), chapter on Delcassé pp 87-186.

- ↑ Norman Rich, Great Power Diplomacy since 1914 (2003) pp 148-49.

- ↑ "Treaty Heralded New Era in Franco-German Ties". Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ "French, German Presidents Mark World War I Anniversary". France News.Net. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ↑ "Franco-German University - facts & figures". dfh-ufa.org. Archived from the original on 2018-03-01. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

Further reading

- Keiger, J.F.V. France and the World since 1870 (2001), a wide ranging survey to the 1990s

- Krotz, Ulrich. History and foreign policy in France and Germany (Springer, 2015).

to 1945

- Albrecht-Carrié, René. A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna (1958), 736pp; basic survey

- Brandenburg, Erich. (1927) From Bismarck to the World War: A History of German Foreign Policy 1870–1914 (1927) online.

- Bury, J.P.T. "Diplomatic History 1900–1912, in C. L. Mowat, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History: Vol. XII: The Shifting Balance of World Forces 1898-1945 (2nd ed. 1968) online pp 112-139.

- Carroll, E. Malcolm, French Public Opinion and Foreign Affairs 1870–1914 (1931). online.

- Carroll, E. Malcolm. Germany and the great powers, 1866–1914: A study in public opinion and foreign policy (1938) online; online at Questia also online review

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2013)

- Gooch, G.P. History of modern Europe, 1878–1919 (2nd ed. 1956) pp 386-413. online, diplomatic history

- Hensel, Paul R. "The Evolution of the Franco-German Rivalry" pp 86–124 in William R. Thompson, ed. Great power rivalries (1999) online

- Hewitson, Mark. "Germany and France before the First World War: a reassessment of Wilhelmine foreign policy." English Historical Review 115.462 (2000): 570-606; argues Germany had a growing sense of military superiority

- Keiger, John F.V. France and the origins of the First World War (1983)

- Langer, William. An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed. 1973); highly detailed outline of events online

- Langer, William. European Alliances and Alignments 1870–1890 (1950); advanced history online

- Langer, William. The Diplomacy of Imperialism 1890–1902 (1950); advanced history online

- MacMillan, Margaret. The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013)

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914 (1991), comprehensive survey

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy since 1914 (2003) comprehensive survey

- Scheck, Raffael. “Lecture Notes, Germany and Europe, 1871–1945” (2008) full text online, a brief textbook by a leading scholar

- Schuman, Frederick L. War and Diplomacy in the French Republic (1931) online

- Steiner, Zara S. The lights that failed: European international history, 1919–1933 (2007), 940pp detailed coverage; online

- Steiner, Zara. The Triumph of the Dark: European International History, 1933–1939 (2011) detailed coverage 1236pp

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 (1954) 638pp; advanced history and analysis of major diplomacy.

- Watt, D.C. "Diplomatic History 1930–1939" in C. L. Mowat, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History: Vol. XII: The Shifting Balance of World Forces 1898-1945 (2nd ed. 1968) online pp 684-734.

- Weinberg, Gerhard.The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany: Diplomatic Revolution in Europe, 1933-36 (v. 1) (1971); The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany: Starting World War II, 1937–1939 (vol 2) (University of Chicago Press, 1980) ISBN 0-226-88511-9.

- Wetzel, David. A Duel of Giants: Bismarck, Napoleon III, and the Origins of the Franco-Prussian War (2003)

- Young, Robert France and the Origins of the Second World War (1996)

Post 1945

- Baun, Michael J. "The Maastricht Treaty as High Politics: Germany, France, and European Integration." Political Science Quarterly (1996): 110#4 pp. 605-624 in JSTOR

- Friend, Julius W. The Linchpin: French-German Relations, 1950–1990 (1991) online

- Friend, Julius W. Unequal Partners: French-German Relations, 1989–2000. (Greenwood 2001)

- Fryer, W. R. "The Republic and the Iron Chancellor: The Pattern of Franco-German Relations, 1871–1890," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (1979), Vol. 29, pp 169-185

- Gordon, Philip H. France, Germany and the Western Alliance. (Westview 1995) ISBN 0-8133-2555-2.

- Gunther, Scott. "A New Identity for Old Europe: How and Why the French Imagined Françallemagne in Recent Years." French Politics, Culture & Society (2011) 29#1

- Krotz, Ulrich. "Three eras and possible futures: a long-term view on the Franco-German relationship a century after the First World War," International Affairs (March 2014) 20#2 pp 337-350

- Krotz, Ulrich, and Joachim Schild. Shaping Europe: France, Germany, and Embedded Bilateralism from the Elysée Treaty to Twenty-First Century Politics (Oxford University Press, 2013)

- Krotz, Ulrich. "Regularized intergovernmentalism: France–Germany and beyond (1963–2009)." Foreign Policy Analysis (2010) 6#2 pp: 147-185.

- Krotz, Ulrich. Structure as Process: The Regularized Intergovernmentalism of Franco-German Bilateralism (Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, Harvard University, 2002) online

- Krotz, Ulrich. "Social Content of the International Sphere: Symbols and Meaning in Franco-German Relations" (Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, 2002.) online

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy since 1914 (2003) comprehensive survey

- Schild, Joachim. "Leadership in Hard Times: Germany, France, and the Management of the Eurozone Crisis." German Politics & Society (2013) 31#1 pp: 24-47.

- Sutton, Michael. France and the construction of Europe, 1944–2007: the geopolitical imperative (Berghahn Books, 2011)

External links

- France and Germany Celebrate 50 Years of Friendship (Spiegel Online interview with Jacques Delors and Joschka Fischer)

- Spanish irritation of excessive dominance of the EU agenda by France & Germany

- The Commissioner for Franco-German Cooperation

- La Gazette de Berlin The Newspaper in French for Germany (1 Page in German)

- The Franco-German Youth Office (FGYO)