Duchenne muscular dystrophy

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| |

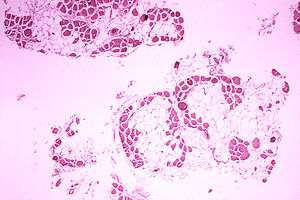

| Microscopic image of the calf muscle from a person with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cross section of muscle shows extensive replacement of muscle fibers by fat cells. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics, pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Muscle weakness, trouble standing up, scoliosis[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Around age 4[1] |

| Causes | Genetic (X-linked recessive)[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing[2] |

| Treatment | Physical therapy, braces, surgery, assisted ventilation[1][2] |

| Prognosis | Average life expectancy 26[3] |

| Frequency | 1 in 5,000 males at birth[2] |

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe type of muscular dystrophy.[2] The symptom of muscle weakness usually begins around the age of four in boys and worsens quickly.[1] Typically muscle loss occurs first in the upper legs and pelvis followed by those of the upper arms.[2] This can result in trouble standing up.[2] Most are unable to walk by the age of 12.[1] Affected muscles may look larger due to increased fat content.[2] Scoliosis is also common.[2] Some may have intellectual disability.[2] Females with a single copy of the defective gene may show mild symptoms.[2]

The disorder is X-linked recessive.[2] About two thirds of cases are inherited from a person's mother, while one third of cases are due to a new mutation.[2] It is caused by a mutation in the gene for the protein dystrophin.[2] Dystrophin is important to maintain the muscle fiber's cell membrane.[2] Genetic testing can often make the diagnosis at birth.[2] Those affected also have a high level of creatine kinase in their blood.[2]

Although there is no known cure, physical therapy, braces, and corrective surgery may help with some symptoms.[1] Assisted ventilation may be required in those with weakness of breathing muscles.[2] Medications used include steroids to slow muscle degeneration, anticonvulsants to control seizures and some muscle activity, and immunosuppressants to delay damage to dying muscle cells.[1]

DMD affects about one in 5,000 males at birth.[2] It is the most common type of muscular dystrophy.[2] The average life expectancy is 26;[3] however, with excellent care, some may live into their 30s or 40s.[2] Gene therapy, as a treatment, is in the early stages of study in humans.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptom of DMD, a progressive neuromuscular disorder, is muscle weakness associated with muscle wasting with the voluntary muscles being first affected, especially those of the hips, pelvic area, thighs, shoulders, and calves. Muscle weakness also occurs later, in the arms, neck, and other areas. Calves are often enlarged. Symptoms usually appear before age six and may appear in early infancy. Other physical symptoms are:

- Awkward manner of walking, stepping, or running – (patients tend to walk on their forefeet, because of an increased calf muscle tone. Also, toe walking is a compensatory adaptation to knee extensor weakness.)

- Frequent falls

- Fatigue

- Difficulty with motor skills (running, hopping, jumping)

- Lumbar hyperlordosis, possibly leading to shortening of the hip-flexor muscles. This has an effect on overall posture and a manner of walking, stepping, or running.

- Muscle contractures of Achilles tendon and hamstrings impair functionality because the muscle fibers shorten and fibrose in connective tissue

- Progressive difficulty walking

- Muscle fiber deformities

- Pseudohypertrophy (enlarging) of tongue and calf muscles. The muscle tissue is eventually replaced by fat and connective tissue, hence the term pseudohypertrophy.

- Higher risk of neurobehavioral disorders (e.g., ADHD), learning disorders (dyslexia), and non-progressive weaknesses in specific cognitive skills (in particular short-term verbal memory), which are believed to be the result of absent or dysfunctional dystrophin in the brain.

- Eventual loss of ability to walk (usually by the age of 12)

- Skeletal deformities (including scoliosis in some cases)

- Trouble getting up from lying or sitting position[4]

According to Lewis P. Rowland, in the anthology Gene Expression In Muscle, if a boy is affected with DMD, the condition can be observed clinically from the moment he takes his first steps. It becomes harder and harder for the boy to walk; his ability to walk usually completely disintegrates between the time the boy is 9 to 12 years of age. Most men affected with DMD become essentially “paralyzed from the neck down” by the age of 21.[5] Muscle wasting begins in the legs and pelvis, then progresses to the muscles of the shoulders and neck, followed by loss of arm muscles and respiratory muscles. Calf muscle enlargement (pseudohypertrophy) is quite obvious. Cardiomyopathy particularly (dilated cardiomyopathy) is common, but the development of congestive heart failure or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) is only occasional.

- A positive Gowers' sign reflects the more severe impairment of the lower extremities muscles. The child helps himself to get up with upper extremities: first by rising to stand on his arms and knees, and then "walking" his hands up his legs to stand upright.

- Affected children usually tire more easily and have less overall strength than their peers.

- Creatine kinase (CPK-MM) levels in the bloodstream are extremely high.

- An electromyography (EMG) shows that weakness is caused by destruction of muscle tissue rather than by damage to nerves.

- Genetic testing can reveal genetic errors in the Xp21 gene.

- A muscle biopsy (immunohistochemistry or immunoblotting) or genetic test (blood test) confirms the absence of dystrophin, although improvements in genetic testing often make this unnecessary.

- Abnormal heart muscle (cardiomyopathy)

- Congestive heart failure or irregular heart rhythm (arrhythmia)

- Deformities of the chest and back (scoliosis)

- Enlarged muscles of the calves, buttocks, and shoulders (around age 4 or 5). These muscles are eventually replaced by fat and connective tissue (pseudohypertrophy).

- Loss of muscle mass (atrophy)

- Muscle contractures in the heels, legs

- Muscle deformities

- Respiratory disorders, including pneumonia and swallowing with food or fluid passing into the lungs (in late stages of the disease)[6]

Cause

DMD is caused by a mutation of the dystrophin gene at locus Xp21, located on the short arm of the X chromosome.[7] Dystrophin is responsible for connecting the cytoskeleton of each muscle fiber to the underlying basal lamina (extracellular matrix), through a protein complex containing many subunits. The absence of dystrophin permits excess calcium to penetrate the sarcolemma (the cell membrane).[8] Alterations in calcium and signalling pathways cause water to enter into the mitochondria, which then burst.

In skeletal muscle dystrophy, mitochondrial dysfunction gives rise to an amplification of stress-induced cytosolic calcium signals and an amplification of stress-induced reactive-oxygen species production. In a complex cascading process that involves several pathways and is not clearly understood, increased oxidative stress within the cell damages the sarcolemma and eventually results in the death of the cell. Muscle fibers undergo necrosis and are ultimately replaced with adipose and connective tissue.

DMD is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern. Females typically are carriers of the genetic trait while males are affected. A female carrier will be unaware she carries a mutation until she has an affected son. The son of a carrier mother has a 50% chance of inheriting the defective gene from his mother. The daughter of a carrier mother has a 50% chance of being a carrier and a 50% chance of having two normal copies of the gene. In all cases, an unaffected father either passes a normal Y to his son or a normal X to his daughter. Female carriers of an X-linked recessive condition, such as DMD, can show symptoms depending on their pattern of X-inactivation. DMD has an incidence of one in 3,600 male infants.[6] Mutations within the dystrophin gene can either be inherited or occur spontaneously during germline transmission.

DMD can occur in females who have an affected father and a carrier mother, although this rarely occurs. The daughter of a carrier mother and an affected father will have a 50% chance of being a carrier as they will always inherit the affected X-chromosome from their father or will have a 50% chance of also inheriting the affected X-chromosome from their mother and thus will be affected.[9]

Disruption of the blood-brain barrier has been seen to be a noted feature in the development of DMD.[10]

Diagnosis

Genetic counseling is advised for people with a family history of the disorder. DMD can be detected with about 95% accuracy by genetic studies performed during pregnancy.[6]

DNA test

The muscle-specific isoform of the dystrophin gene is composed of 79 exons, and DNA testing and analysis can usually identify the specific type of mutation of the exon or exons that are affected. DNA testing confirms the diagnosis in most cases.[11]

Muscle biopsy

If DNA testing fails to find the mutation, a muscle biopsy test may be performed.[12] A small sample of muscle tissue is extracted using a biopsy needle. The key tests performed on the biopsy sample for DMD are immunocytochemistry and immunoblotting for dystrophin, and should be interpreted by an experienced neuromuscular pathologist.[13] These tests provide information on the presence or absence of the protein. Absence of the protein is a positive test for DMD. Where dystrophin is present, the tests indicate the amount and molecular size of dystrophin, helping to distinguish DMD from milder dystrophinopathy phenotypes.[14] Over the past several years, DNA tests have been developed that detect more of the many mutations that cause the condition, and muscle biopsy is not required as often to confirm the presence of DMD.[15]

Prenatal tests

DMD is carried by an X-linked recessive gene. Males have only one X chromosome, so one copy of the mutated gene will cause DMD. Fathers cannot pass X-linked traits on to their sons, so the mutation is transmitted by the mother.[16]

If the mother is a carrier, and therefore one of her two X chromosomes has a DMD mutation, a 50% chance exists that a female child will inherit that mutation as one of her two X chromosomes, and be a carrier. If that carrier has a male child, there is a 50% chance that he will inherit the X chromosome with the mutation, and will have DMD. Prenatal tests can tell whether the unborn child has the most common mutations. Many mutations are responsible for DMD, and some have not been identified, so genetic testing only works when family members with DMD have an identified mutation.

Prior to invasive testing, determination of the fetal sex is important; while males are sometimes affected by this X-linked disease, female DMD is extremely rare. This can be achieved by ultrasound scan at 16 weeks or more recently by free fetal DNA testing. Chorion villus sampling (CVS) can be done at 11–14 weeks, and has a 1% risk of miscarriage. Amniocentesis can be done after 15 weeks, and has a 0.5% risk of miscarriage. Fetal blood sampling can be done around 18 weeks. Another option in the case of unclear genetic test results is fetal muscle biopsy.

Treatment

No cure for DMD is known, and an ongoing medical need has been recognized by regulatory authorities.[17]

Treatment is generally aimed at controlling the onset of symptoms to maximize the quality of life which can be measured using specific questionnaires,[18] and include:

- Corticosteroids such as prednisolone and deflazacort lead to short-term improvements in muscle strength and function up to 2 years.[19] Corticosteroids have also been reported to help prolong walking, though the evidence for this is not robust.[20]

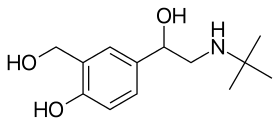

- Randomised control trials have shown that β2 agonists increase muscle strength, but do not modify disease progression. Follow-up time for most RCTs on β2 agonists is only around 12 months, hence results cannot be extrapolated beyond that time frame.

- Mild, nonjarring physical activity such as swimming is encouraged. Inactivity (such as bed rest) can worsen the muscle disease.

- Physical therapy is helpful to maintain muscle strength, flexibility, and function.

- Orthopedic appliances (such as braces and wheelchairs) may improve mobility and the ability for self-care. Form-fitting removable leg braces that hold the ankle in place during sleep can defer the onset of contractures.

- Appropriate respiratory support as the disease progresses is important.

- Cardiac problems may require a pacemaker.[21]

Comprehensive multidisciplinary care standards/guidelines for DMD have been developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and were published in two parts in The Lancet Neurology in 2010.[22]

Physical therapy

Physical therapists are concerned with enabling patients to reach their maximum physical potential. Their aim is to:

- minimize the development of contractures and deformity by developing a programme of stretches and exercises where appropriate

- anticipate and minimize other secondary complications of a physical nature by recommending bracing and durable medical equipment

- monitor respiratory function and advise on techniques to assist with breathing exercises and methods of clearing secretions

Respiration assistance

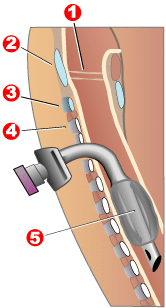

Modern "volume ventilators/respirators," which deliver an adjustable volume (amount) of air to the person with each breath, are valuable in the treatment of people with muscular dystrophy-related respiratory problems. The ventilator may require an invasive endotracheal or tracheotomy tube through which air is directly delivered, but for some people, noninvasive delivery through a face mask or mouthpiece is sufficient. Positive airway pressure machines, particularly bilevel ones, are sometimes used in this latter way. The respiratory equipment may easily fit on a ventilator tray on the bottom or back of a power wheelchair with an external battery for portability.

Ventilator treatment may start in the mid- to late teens when the respiratory muscles can begin to collapse. If the vital capacity has dropped below 40% of normal, a volume ventilator/respirator may be used during sleeping hours, a time when the person is most likely to be underventilating (hypoventilating). Hypoventilation during sleep is determined by a thorough history of sleep disorder with an oximetry study and a capillary blood gas (see pulmonary function testing).

A cough assist device can help with excess mucus in lungs by hyperinflation of the lungs with positive air pressure, then negative pressure to get the mucus up. If the vital capacity continues to decline to less than 30 percent of normal, a volume ventilator/respirator may also be needed during the day for more assistance. The person gradually will increase the amount of time using the ventilator/respirator during the day as needed. However, there are also people with the disease in their 20s who have no need for a ventilator.

Prognosis

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a rare progressive disease which eventually affects all voluntary muscles and involves the heart and breathing muscles in later stages. As of 2013, the life expectancy is estimated to be around 25,[6] but this varies. With excellent medical care males are often living into their 30s.[23]

In rare cases, people with DMD have been seen to survive into their forties or early fifties, with proper positioning in wheelchairs and beds, and the use of ventilator support (via tracheostomy or mouthpiece), airway clearance, and heart medications.[24] Early planning of the required supports for later-life care has shown greater longevity for people with DMD.[25]

Curiously, in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the lack of dystrophin is associated with increased calcium levels and skeletal muscle myonecrosis. The intrinsic laryngeal muscles (ILMs) are protected and do not undergo myonecrosis.[26] ILMs have a calcium regulation system profile suggestive of a better ability to handle calcium changes in comparison to other muscles, and this may provide a mechanistic insight for their unique pathophysiological properties.[27] The ILM may facilitate the development of novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of muscle wasting in a variety of clinical scenarios.[28]

History

The disease was first described by the Neapolitan physician Giovanni Semmola in 1834 and Gaetano Conte in 1836.[29][30][31] However, DMD is named after the French neurologist Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne (1806–1875), who in the 1861 edition of his book Paraplegie hypertrophique de l'enfance de cause cerebrale, described and detailed the case of a boy who had this condition. A year later, he presented photos of his patient in his Album de photographies pathologiques. In 1868, he gave an account of 13 other affected children. Duchenne was the first to do a biopsy to obtain tissue from a living patient for microscopic examination.[32][33]

Notable cases

Alfredo Ferrari (born January 1932 in Modena), nicknamed Alfredino or Dino, was the son of Enzo Ferrari. He designed the 1.5 L DOHC V6 engine for F2 at the end of 1955. Dino never saw the engine; he died 30 June 1956 in Modena at the age of 24, before his namesake automobiles Fiat Dino and Dino (automobile) were produced.

Rapper Darius Weems had the disease and used his notoriety to raise awareness and funds for treatment.[34] He died at the age of 27. His brother also suffered from the disease until his death at age 19. Darius Goes West is a documentary that depicts his journey of growth and acceptance of having the disease. A book entitled The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving, was released in 2012, written by Jonathan Evison. Netflix produced a film, titled The Fundamentals of Caring, in 2016 based on the novel. Both media depict a young man suffering from the disease.

Research

Current research includes exon-skipping, stem cell replacement therapy, analog up-regulation, gene replacement, and supportive care to slow disease progression.

Exon-skipping

Antisense oligonucleotides (oligos), structural analogs of DNA, are the basis of a potential therapy for patients afflicted with DMD. The compounds allow faulty parts of the dystrophin gene to be skipped when it is transcribed to RNA for protein production, permitting a still-truncated but more functional version of the protein to be produced.[35]

Two kinds of antisense oligos, 2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate oligos (like drisapersen) and Morpholino oligos (like eteplirsen), have been tested in clinical trials for DMD and have restored some dystrophin expression in muscles of DMD patients with a particular class of DMD-causing mutations. Clinical trials are ongoing, with one oligo targeting dystrophin exon 51 (eteplirsen) approved by the US FDA.[36]

Oligo-mediated exon skipping has resulted in clinical improvement in 12 patients in a Phase 1-2a study. On a standard test, the 6-minute walk test, patients whose performance had been declining instead improved, from 385 meters to 420 meters.[37][38] DMD may result from mRNA that contains out-of-frame mutations (e.g. deletions, insertions or splice site mutations), resulting in frameshift or early termination so that in most muscle fibers no functional dystrophin is produced (though some revertant muscle fibers produce some dystrophin). In many cases an antisense oligonucleotide can be used to trigger skipping of an adjacent exon to restore the reading frame and production of partially functional dystrophin.

Patients with Becker's muscular dystrophy, which is milder than DMD, have a form of dystrophin which is functional even though it is shorter than normal dystrophin.[39] In 1990 England et al. noticed that a patient with mild Becker muscular dystrophy was lacking 46% of his coding region for dystrophin.[39] This functional, yet truncated, form of dystrophin gave rise to the notion that shorter dystrophin can still be therapeutically beneficial. Concurrently, Kole et al. had modified splicing by targeting pre-mRNA with antisense oligonucleotides (AONs).[40] Kole demonstrated success using splice-targeted AONs to correct missplicing in cells removed from beta-thalassemia patients[41][42] Wilton's group tested exon skipping for muscular dystrophy.[43][44] Successful preclinical research led to the current efforts to use splice-modifying oligos to change DMD dystrophin to a more functional form of dystrophin, in effect converting Duchenne MD into Becker MD.

Though AONs hold promise, one of their major pitfalls is the need for periodic redelivery into muscles. Systemic delivery on a recurring basis is being tested in humans.[45] To circumvent the requirement for periodic oligo delivery, a long-term exon-skip therapy is being explored. This therapy consists of modifying the U7 small nuclear RNA at the 5' end of the non-translated RNA to target regions within pre-mRNA. This has been shown to work in the DMD equivalent mouse, mdx.[46]

Stem cell replacement

Though stem cells isolated from the muscle (satellite cells) have the ability to differentiate into myotubes when injected directly into the muscle of animals, they lack the ability to spread systemically throughout. To effectively deliver a therapeutic dose to an isolated muscle it would require direct injections to that muscle every 2mm.[47] This problem was circumvented by using another multipotent stem cell, termed pericytes, that are located within the blood vessels of skeletal muscle. These cells have the ability to be delivered systemically and uptaken by crossing the vascular barrier. Once past the vasculature, pericytes have the ability to fuse and form myotubes.[48] This means that they can be injected arterially, crossing through arterial walls into muscle, where they can differentiate into potentially functional muscle. These findings show potential for stem cell therapy of DMD. The pericyte-derived cells would be extracted, grown in culture, and then these cells would be injected into the blood stream where the possibility exists that they might find their way into injured regions of skeletal muscle.

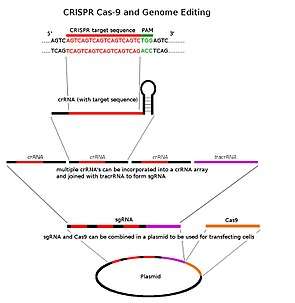

Gene therapy

Researchers are working on a gene editing method to correct a mutation that leads to Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).[49] Researchers used a technique called CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing, which can precisely remove a mutation in the dystrophin gene in DNA, allowing the body’s DNA repair mechanisms to replace it with a normal copy of the gene.[50] The benefit of this over other gene therapy techniques is that it can permanently correct the “defect” in a gene rather than just transiently adding a “functional” one.

Genome editing through the CRISPR/Cas9 system is not currently feasible in humans. However, it may be possible, through advancements in technology, to use this technique to develop therapies for DMD in the future.[51][52] In 2007, researchers did the world's first clinical (viral-mediated) gene therapy trial for Duchenne MD.[53]

Biostrophin is a delivery vector for gene therapy in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy.[54]

Clinical trials

While PTC124 showed promising results in mice,[55][56] the Phase II trial was suspended when participants did not show significant increases in the six-minute walk distance.[57] The Phase II trial of ACE-031 (a decoy receptor) was suspended due to safety issues.[58][59]

Safety and efficacy studies of antisense oligonucleotides for exon skipping in Duchenne muscular dystrophy with Morpholino oligos (e.g. eteplirsen)[60] and with 2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate oligos (e.g. drisapersen)[61] are in progress.

In 2011, in a study by the UK Medical Research Council and Sarepta Therapeutics (formerly known as AVI BioPharma), researchers trialled a new drug, known as Eteplirsen(AVI-4658), designed to make the body bypass genetic mutations when producing dystrophin. When given to 19 children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, researchers found that higher doses of the drug led to an increase in dystrophin. Researchers believe that drugs which are designed to make the body “skip over” mutations in this way could be used to treat approximately 83% of Duchenne muscular dystrophy cases. However, the drug used in this trial only targeted mutations in a region implicated in 13% of cases. This study was conducted well and demonstrated the potential of this approach for increasing the levels of dystrophin in the short term. The trial’s principal aim was to work out the appropriate dosages of the drug, therefore the drug’s safety profile and effects will need to be confirmed in larger, longer-term studies, particularly as patients would need to take it for the rest of their lives (or until a better treatment is available).[62]

A small study published in May 2014 in the journal Neurology showed that the erectile dysfunction drug sildenafil could improve blood flow in boys affected with Duchenne MD. A larger and longer trial of the related drug tadalafil is underway to determine if improved blood flow will translate into improved muscle function.[63]

Preclinical trials

Rimeporide, a sodium–hydrogen antiporter 1 inhibitor, is in preclinical trials as of May 2015.[64]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "NINDS Muscular Dystrophy Information Page". NINDS. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "Muscular Dystrophy: Hope Through Research". NINDS. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- 1 2 Lisak, Robert P.; Truong, Daniel D.; Carroll, William; Bhidayasiri, Roongroj (2011). International Neurology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 222. ISBN 9781444317015.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- ↑ Rowland, L. P. (1985). Clinical Perspective: Phenotypic Expression In Muscular Dhystrophy. In R. C. Strohman & S. Wolf (Eds.), Gene Expression in Muscle (pp. 3-5). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- 1 2 3 4 MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - # 310200 - MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY, DUCHENNE TYPE; DMD". Omim.org. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ "Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Pathophysiological Implications of Mitochondrial Calcium Signaling and ROS Production". Web.archive.org. 2012-05-02. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ http://genetics.thetech.org/ask-a-geneticist/genetics-duchenne-muscular-dystrophy-dmd

- ↑ Nico, B; Ribatti, D; Gillespie, D (January 2012). "Morphofunctional aspects of the blood-brain barrier". Current Drug Metabolism. 13 (1): 50–60. doi:10.2174/138920012798356970. PMID 22292807.

- ↑ "University of Utah Muscular Dystrophy". Genome.utah.edu. 2009-11-28. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ Bushby, Katharine; Finkel, Richard; Birnkrant, David J; Case, Laura (January 2010). "Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management". The Lancet Neurology. 9 (1): 77–93. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70271-6. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ Nicholson, L. V.; Johnson, M. A.; Bushby, K. M.; Gardner-Medwin, D.; Curtis, A.; Ginjaar, I. B.; den Dunnen, J. T.; Welch, J. L.; Butler, T. J.; Bakker, E. (1 September 1993). "Integrated study of 100 patients with Xp21 linked muscular dystrophy using clinical, genetic, immunochemical, and histopathological data. Part 2. Correlations within individual patients". Journal of Medical Genetics. 30 (9): 737–744. doi:10.1136/jmg.30.9.737. ISSN 0022-2593. PMC 1016530. PMID 8411068.

- ↑ Muntoni, F. (28 August 2001). "Is a muscle biopsy in Duchenne dystrophy really necessary?". Neurology. 57 (4): 574–575. doi:10.1212/wnl.57.4.574. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 11524463.

- ↑ Flanigan, Kevin M.; Niederhausern, Andrew von; Dunn, Diane M.; Alder, Jonathan; Mendell, Jerry R.; Weiss, Robert B. (1 April 2003). "Rapid Direct Sequence Analysis of the Dystrophin Gene". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 931–939. doi:10.1086/374176. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1180355. PMID 12632325.

- ↑ "Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy, National Institutes of health". Ghr.nlm.nih.gov. 2013-02-11. Archived from the original on 2013-02-07. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ "Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Statement". Drug Safety and Availability. US FDA. 2014-10-31. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02.

- ↑ Dany, Antoine; Barbe, Coralie; Rapin, Amandine; Réveillère, Christian; Hardouin, Jean-Benoit; Morrone, Isabella; Wolak-Thierry, Aurore; Dramé, Moustapha; Calmus, Arnaud; Sacconi, Sabrina; Bassez, Guillaume; Tiffreau, Vincent; Richard, Isabelle; Gallais, Benjamin; Prigent, Hélène; Taiar, Redha; Jolly, Damien; Novella, Jean-Luc; Boyer, François Constant (2015). "Construction of a Quality of Life Questionnaire for slowly progressive neuromuscular disease". Quality of Life Research. 24 (11): 2615–2623. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-1013-8. ISSN 0962-9343.

- ↑ Falzarano, MS; Scotton, C; Passarelli; Ferlini A (2015). "Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from diagnosis to therapy". Molecules. 20 (10): 18168–18184. doi:10.3390/molecules201018168. PMID 26457695.

- ↑ Matthews, E; Brassington, R; Kuntzer, T; Jichi, F; Manzur, AY (5 May 2016). "Corticosteroids for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD003725. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003725.pub4. PMID 27149418. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ Verhaert, David; Richards, Kathryn; Rafael-Fortney, Jill A.; Raman, Subha V. (2011-01-01). "Cardiac Involvement in Patients with Muscular Dystrophies: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Phenotype and Genotypic Considerations". Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 4 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.960740. ISSN 1941-9651. PMC 3057042. PMID 21245364.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management" (PDF). doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70271-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ "Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | Muscular Dystrophy Campaign". Muscular-dystrophy.org. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ Kieny, P.; Chollet, S.; Delalande, P.; Le Fort, M.; Magot, A.; Pereon, Y.; Perrouin Verbe, B. (2013-09-01). "Evolution of life expectancy of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy at AFM Yolaine de Kepper centre between 1981 and 2011". Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 56 (6): 443–454. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2013.06.002.

- ↑ Rodger, Sunil; Steffensen, Birgit F; Lochmüller, Hanns (2012-11-22). "Transition from childhood to adulthood in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD)". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 7 (Suppl 2): A8. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-S2-A8. ISSN 1750-1172. PMC 3504593.

- ↑ Marques, Maria Julia; Ferretti, Renato; Vomero, Viviane Urbini; Minatel, Elaine; Neto, Humberto Santo (2007). "Intrinsic laryngeal muscles are spared from myonecrosis in themdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Muscle & Nerve. 35 (3): 349–53. doi:10.1002/mus.20697. PMID 17143878.

- ↑ Ferretti, Renato; Marques, Maria Julia; Khurana, Tejvir S.; Santo Neto, Humberto (2015). "Expression of calcium‐buffering proteins in rat intrinsic laryngeal muscles". Physiological Reports. 3 (6): e12409. doi:10.14814/phy2.12409. PMC 4510619. PMID 26109185.

- ↑ Feng, X.; Files, D. Clark; Zhang, T. (2014). "Intrinsic Laryngeal Muscles and Potential Treatments for Skeletal Muscle-Wasting Disorders". Austin Journal of Otolaryngology. 1 (1): 3. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26.

- ↑ Politano, Luisa. "Cardiomiologia e Genetica Medica" [Cardiomyology and Medical Genetics] (in Italian). Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ↑ De Rosa, Giulio (October 2005). "Da Conte a Duchenne" [By Conte in Duchenne]. DM (in Italian). Unione Italiana Lotta alla Distrofia Muscolare. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ↑ Nigro, G (2010). "One-hundred-seventy-five years of Neapolitan contributions to the fight against the muscular diseases". Acta Myologica. 29 (3): 369–91. PMC 3146338. PMID 21574522.

- ↑ "Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Medterms.com. 2011-04-27. Archived from the original on 2012-08-06. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ doctor/950 at Who Named It?

- ↑ McFadden, Cynthia (November 22, 2012). "Darius Weems' Next Chapter: Rap Star With Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Tries Clinical Trial". Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ Dunckley MG, Manoharan M, Villiet P, Eperon IC, Dickson G (1998). "Modification of splicing in the dystrophin gene in cultured Mdx muscle cells by antisense oligoribonucleotides". Human Molecular Genetics. 7 (7): 1083–90. doi:10.1093/hmg/7.7.1083. PMID 9618164.

- ↑ "FDA grants accelerated approval to first drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy" (Press release). FDA Newsroom. FDA. September 19, 2016. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ↑ Goemans NM, Tulinius M, van den Akker JT, Burm BE, Ekhart PF, Heuvelmans N, Holling T, Janson AA, Platenburg GJ, Sipkens JA, Sitsen JM, Aartsma-Rus A, van Ommen GJ, Buyse G, Darin N, Verschuuren JJ, Campion GV, de Kimpe SJ, van Deutekom JC (2011). "Systemic Administration of PRO051 in Duchenne's Muscular Dystrophy". New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (16): 1513–1522. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1011367. PMID 21428760.

- ↑ Study Shows Patients With Duchenne's Muscular Dystrophy Are Walking Better With PRO051 Treatment. Archived 2011-05-02 at the Wayback Machine. By Daniel J. DeNoon WebMD Health News. March 23, 2011

- 1 2 England SB, Nicholson LV, Johnson MA, Forrest SM, Love DR, Zubrzycka-Gaarn EE, Bulman DE, Harris JB, Davies KE (1990). "Very mild muscular dystrophy associated with the deletion of 46% of dystrophin". Nature. 343 (6254): 180–2. Bibcode:1990Natur.343..180E. doi:10.1038/343180a0. PMID 2404210.

- ↑ Dominski Z, Kole R (1993). "Restoration of correct splicing in thalassemic pre-mRNA by antisense oligonucleotides". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (18): 8673–7. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.8673D. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.18.8673. PMC 47420. PMID 8378346.

- ↑ Lacerra G, Sierakowska H, Carestia C, Fucharoen S, Summerton J, Weller D, Kole R (2000). "Restoration of hemoglobin A synthesis in erythroid cells from peripheral blood of thalassemic patients". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (17): 9591–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.9591L. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.17.9591. PMC 16909. PMID 10944225.

- ↑ Suwanmanee T, Sierakowska H, Lacerra G, Svasti S, Kirby S, Walsh CE, Fucharoen S, Kole R (2002). "Restoration of human beta-globin gene expression in murine and human IVS2-654 thalassemic erythroid cells by free uptake of antisense oligonucleotides". Mol. Pharmacol. 62 (3): 545–53. doi:10.1124/mol.62.3.545. PMID 12181431.

- ↑ Wilton SD, Lloyd F, Carville K, Fletcher S, Honeyman K, Agrawal S, Kole R (1999). "Specific removal of the nonsense mutation from the mdx dystrophin mRNA using antisense oligonucleotides". Neuromuscul Disord. 9 (5): 330–8. doi:10.1016/S0960-8966(99)00010-3. PMID 10407856.

- ↑ Wilton SD, Fall AM, Harding PL, McClorey G, Coleman C, Fletcher S (2007). "Antisense oligonucleotide-induced exon skipping across the human dystrophin gene transcript". Mol. Ther. 15 (7): 1288–96. doi:10.1038/sj.mt.6300095. PMID 17285139.

- ↑ "Dose-Ranging Study of AVI-4658 to Induce Dystrophin Expression in Selected Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) Patients - Full Text View". ClinicalTrials.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-12-14. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ Goyenvalle A, Vulin A, Fougerousse F, Leturcq F, Kaplan JC, Garcia L, Danos O (2004). "Rescue of dystrophic muscle through U7 snRNA-mediated exon skipping". Science. 306 (5702): 1796–9. Bibcode:2004Sci...306.1796G. doi:10.1126/science.1104297. PMID 15528407.

- ↑ Morgan JE, Pagel CN, Sherratt T, Partridge TA (1993). "Long-term persistence and migration of myogenic cells injected into pre-irradiated muscles of mdx mice". J. Neurol. Sci. 115 (2): 191–200. doi:10.1016/0022-510X(93)90224-M. PMID 7683332.

- ↑ Dellavalle A, Sampaolesi M, Tonlorenzi R, Tagliafico E, Sacchetti B, Perani L, Innocenzi A, Galvez BG, Messina G, Morosetti R, Li S, Belicchi M, Peretti G, Chamberlain JS, Wright WE, Torrente Y, Ferrari S, Bianco P, Cossu G (2007). "Pericytes of human skeletal muscle are myogenic precursors distinct from satellite cells". Nat. Cell Biol. 9 (3): 255–67. doi:10.1038/ncb1542. PMID 17293855.

- ↑ Long, Chengzu; Li, Hui; Tiburcy, Malte; Rodriguez-Caycedo, Cristina; Kyrychenko, Viktoriia; Zhou, Huanyu; Zhang, Yu; Min, Yi-Li; Shelton, John M. (2018-01-01). "Correction of diverse muscular dystrophy mutations in human engineered heart muscle by single-site genome editing". Science Advances. 4 (1): eaap9004. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aap9004. ISSN 2375-2548.

- ↑ Cohen, Jon (2018-08-30). "Gene editing of dogs offers hope for treating human muscular dystrophy". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aav2676. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ Long, C.; McAnally, J. R.; Shelton, J. M.; Mireault, A. A.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E. N. (2014). "Prevention of muscular dystrophy in mice by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of germline DNA". Science. 345 (6201): 1184–8. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1184L. doi:10.1126/science.1254445. PMC 4398027. PMID 25123483.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (31 December 2015). "Gene Editing Offers Hope for Treating Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, Studies Find". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ Rodino-Klapac, Louise R.; Chicoine, Louis G.; Kaspar, Brian K.; Mendell, Jerry R. (2007). "Gene Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy". Archives of Neurology. 64 (9): 1236–41. doi:10.1001/archneur.64.9.1236. PMID 17846262.

- ↑ Khurdayan, V.K.; Bozzo, J.; Prous, J.R. (2005). "Chronicles in drug discovery". Drug News & Perspectives. 18 (8): 517–22. doi:10.1358/dnp.2005.18.8.953409. PMID 16391721.

- ↑ "Preliminary Results of DMD Clinical Trial Encouraging" (Press release). Muscular Dystrophy Association. October 21, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ↑ "First Demonstration of Muscle Restoration in an Animal Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy" (PDF) (Press release). Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy. April 23, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ↑ "PTC Therapeutics and Genzyme Corporation Announce Preliminary Results from the Phase 2b Clinical Trial of Ataluren for Nonsense Mutation Duchenne/Becker Muscular Dystrophy" (Press release). PTC Therapeutics. March 3, 2010. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT01099761 for "Study of ACE-031 in Subjects With Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ "ACE-031 Clinical Trials in Duchenne MD Stopped for Now | Quest Magazine Online". Quest.mda.org. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00159250 for "Safety and Efficacy Study of Antisense Oligonucleotides in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ "Clinical trial information for 2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate (PRO051) trial". Nederlands trial register. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ Cirak, Sebahattin; Arechavala-Gomeza, Virginia; Guglieri, Michela; Feng, Lucy; Torelli, Silvia; Anthony, Karen; Abbs, Stephen; Garralda, Maria Elena; Bourke, John; Wells, Dominic J; Dickson, George; Wood, Matthew JA; Wilton, Steve D; Straub, Volker; Kole, Ryszard; Shrewsbury, Stephen B; Sewry, Caroline; Morgan, Jennifer E; Bushby, Kate; Muntoni, Francesco (2011). "Exon skipping and dystrophin restoration in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy after systemic phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer treatment: an open-label, phase 2, dose-escalation study". The Lancet. 378 (9791): 595–605. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60756-3. PMC 3156980. PMID 21784508. Lay summary – NHS Choices (July 25, 2011).

- ↑ Nelson, Michael D.; Rader, Florian; Tang, Xiu; Tavyev, Jane; Nelson, Stanley F.; Miceli, M. Carrie; Elashoff, Robert M.; Sweeney, H. Lee; Victor, Ronald G. (2014). "PDE5 inhibition alleviates functional muscle ischemia in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Neurology. 82 (23): 2085–91. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000498. PMC 4118495. PMID 24808022. Lay summary – Medscape Medical News (May 20, 2014).

- ↑ Spreitzer, Helmut (26 May 2015). "Rimeporide". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German). 69 (11): 12.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Duchenne muscular dystrophy. |

- Muscular Dystrophies at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (previously listed below as "Duchenne/Becker Muscular Dystrophy, NCBDDD") at CDC

- Genes and Disease Page at NCBI